Report on Blacklisting : 1 Movies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hold That Ghost in Late 1941 Milton Berle Was Said to Have Quipped, "Things Are Slow in Hollywood

Those Slap-Happy Screamsters Go A’haunting! Saturday, October 23 at 2 & 8 pm only Abbott and Costello’s Hold That Ghost In late 1941 Milton Berle was said to have quipped, "Things are slow in Hollywood. Abbott and Costello haven't made a picture all day." And he was right. fter the smash success of their first starring feature,Buck Privates, (1941) burlesque and Aradio comics Bud Abbott and Lou Costello were the number one box office attraction in the country--and literally saved Universal Studios from bankruptcy. In fact, the only movie that outgrossed Buck Privates at the time was Gone with the Wind. Anxious to keep the team working, Universal Studios had already completed production on their next film, a non-music spoof of two popular film genres of the era--the Haunted House movie and Gangster melodrama--then titled Oh Charlie! (a reference to a running gag in the film where a dead gangster's body keeps turning up). But when the huge box office returns fromBuck Privates began rolling in, Universal temporarily shelved Oh Charlie! to put the team in an- other service themed follow-up, In the Navy. When they returned to Oh Charlie! , Universal discovered test audiences for the film wondered why the Andrews Sisters, who had been in the two previous hits, were absent in this one. So additional re-shoots were required to include the trio, now making it a horror/ comedy, with a couple of songs thrown in. The title was eventually changed to Hold That Ghost and became the third smash hit for Abbott and Costello that year, continuing a string of successes that would keep them among the top box office attractions for the next ten years and would also serve as the inspiration for another classic, 1948's Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. -

George Seaton Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

George Seaton 电影 串行 (大全) 36 Hours https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/36-hours-227532/actors Chicken Every https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/chicken-every-sunday-2963389/actors Sunday What's So Bad About https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/what%27s-so-bad-about-feeling-good%3F-3204274/actors Feeling Good? Little Boy Lost https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-boy-lost-3225457/actors Showdown https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/showdown-3282975/actors For Heaven's Sake https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/for-heaven%27s-sake-3352342/actors Anything Can https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/anything-can-happen-4000927/actors Happen Where Do We Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/where-do-we-go-from-here%3F-4244332/actors from Here? Apartment for Peggy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/apartment-for-peggy-4779186/actors The Big Lift https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-big-lift-495924/actors Diamond Horseshoe https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/diamond-horseshoe-5270833/actors The Hook https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-hook-562304/actors Junior Miss https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/junior-miss-6313371/actors Williamsburg: the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/williamsburg%3A-the-story-of-a-patriot-8021151/actors Story of a Patriot The Counterfeit https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-counterfeit-traitor-908713/actors Traitor 蓬門淑女 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E8%93%AC%E9%96%80%E6%B7%91%E5%A5%B3-1305029/actors -

William Witney Ùيلم قائمة (ÙÙŠÙ

William Witney ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… وغراÙÙ ŠØ§) Tarzan's Jungle Rebellion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tarzan%27s-jungle-rebellion-10378279/actors The Lone Ranger https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lone-ranger-10381565/actors Trail of Robin Hood https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/trail-of-robin-hood-10514598/actors Twilight in the Sierras https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twilight-in-the-sierras-10523903/actors Young and Wild https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/young-and-wild-14646225/actors South Pacific Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-pacific-trail-15628967/actors Border Saddlemates https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/border-saddlemates-15629248/actors Old Oklahoma Plains https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-oklahoma-plains-15629665/actors Iron Mountain Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/iron-mountain-trail-15631261/actors Old Overland Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-overland-trail-15631742/actors Shadows of Tombstone https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shadows-of-tombstone-15632301/actors Down Laredo Way https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/down-laredo-way-15632508/actors Stranger at My Door https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stranger-at-my-door-15650958/actors Adventures of Captain Marvel https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adventures-of-captain-marvel-1607114/actors The Last Musketeer https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-musketeer-16614372/actors The Golden Stallion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-golden-stallion-17060642/actors Outlaws of Pine Ridge https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/outlaws-of-pine-ridge-20949926/actors The Adventures of Dr. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Using Film and Critical Pedagogy in the Standards-Based Classroom

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF John D. Divelbiss for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on April 28, 2014. Title: Re-Viewing the Canon: Using Film and Critical Pedagogy in the Standards-based Classroom Abstract approved: __________________________________________________________________ Jon R. Lewis This thesis analyzes the efficacy of emancipatory (critical) pedagogical practices in an educational climate of standards-based reform. Using two films noir of the blacklist era—Body and Soul and Crossfire—as the core texts of a unit in a secondary school curriculum, I argue that an emphasis on student agency and a de-centering of curriculum and instruction is not only compatible with national reforms like the Common Core State Standards but is essential for English/language arts classrooms in the 21st century. In addition to a scholarly review of critical pedagogy and media literacy, and close readings of the two films themselves, this thesis also ends with an informal case study in which both films-as-texts were taught to 9th grade students. By combining theory and practice, I was able to model the praxis at the heart of critical pedagogy, what Paulo Freire calls in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” The films of the blacklist match current national mandates for relevant texts, for media and visual literacy, and for authentic and emancipatory pedagogy. Narrowing down even further on two highly-regarded films released in 1947, the same year the blacklist was initiated, allows for an analysis of the artistic and aesthetic complexities of the texts as well as the high-stakes terms of the political engagements of the blacklist. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Eureka Entertainment to Release a LETTER to THREE WIVES, The

Dual Format Cat. No.| EKA70187 Certificate| U Director| Joseph L. MANKIEWICZ Dual Format Barcode| 5060000701876 Run Time| 103 min. Year| 1949 Dual Format SRP| £19.99 OAR| 1.37:1 OAR Country| USA Release Date| 29 June 2015 Picture| Black & White Language| English Genre| Drama / Romance Subtitles| English (Optional) stunning romantic drama from writer-director Joseph L. Mankiewicz (All About Eve , The Barefoot Contessa ), A A Letter to Three Wives explores the domestic travails of three couples and the woman that brings them to the brink of crisis. The letter of the title is written with a poisonous pen: the three women (portrayed by Jeanne Crain , Linda Darnell , and Ann Sothern ) receive a note stating that one of their husbands has run off with a woman named Addie Ross – which husband in particular, however, remains unmentioned, though each husband had their own affinity for Ross. And so amid the women’s mounting anxiety commences a series of flashbacks, each telling the story of how the three individual marriages had come in their own way to be so strained at the present... A spectacular success at the time of its release, A Letter to Three Wives was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, and earned Mankiewicz the Academy Awards for both Best Director and Best Screenplay. The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present A Letter to Three Wives in a special Dual Format edition that includes the film on Blu-ray for the first time in the UK. “Despite its emotional intensity, the film is comic, effervescently so, and its magical ending lends -

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 Min

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 min All About Eve received 14 Academy Award nominations and won 6 of them: picture, director, supporting actor, sound, screenplay, costume design. It probably would have won two more if four members of the cast hasn’t been in direct competition with one another: Davis and Baxter for Best Actress and Celeste Holm and Thelma Ritter for Best Supporting Actress. The story is that the studio tried to get Baxter to go for Supporting but she refused because she already had one of those and wanted to move up. Years later, the same story goes, she allowed as maybe she made a bad career move there and Bette David allowed as she was finally right about something. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz Written by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (screenplay) Mary Orr (story "The Wisdom of Eve", uncredited) Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck Music Alfred Newman Cinematography Milton R. Krasner Film Editing Barbara McLean Art Direction George W. Davis and Lyle R. Wheeler Eddie Fisher…Stage Manager Set Decoration Thomas Little and Walter M. Scott William Pullen…Clerk Claude Stroud…Pianist Cast Eugene Borden…Frenchman Bette Davis…Margo Channing Helen Mowery…Reporter Anne Baxter…Eve Harrington Steven Geray…Captain of Waiters George Sanders…Addison DeWitt Celeste Holm…Karen Richards Joseph L. Mankiewicz (b. February 11, 1909 in Wilkes- Gary Merrill…Bill Simpson Barre, Pennsylvania—d. February 5, 1993, age 83, in Hugh Marlowe…Lloyd Richards Bedford, New York) started in the film industry Gregory Ratoff…Max Fabian translating intertitle cards for Paramount in Berlin. -

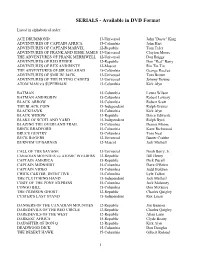

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S

TV/Series 10 | 2016 Guerres en séries (II) “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1764 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.1764 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) », TV/Series [Online], 10 | 2016, Online since 01 December 2016, connection on 05 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1764 ; DOI : 10.4000/ tvseries.1764 This text was automatically generated on 5 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and t... 1 “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) Dennis Tredy 1 If the title of this paper quotes part of the refrain from Edwin Starr’s 1970 protest song, “War,” the song’s next line, proclaiming that war is good for “absolutely nothing” seems inaccurate, at least in terms of successful television sitcoms of from the 1950s to the 1970s. In fact, while Starr’s song was still an anti-Vietnam War battle cry, ground- breaking television programs like M*A*S*H (CBS, 1972-1983) were using laughter and tongue-in-cheek treatment of the horrors of war to provide a somewhat more palatable expression of the growing anti-war sentiment to American audiences. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew.