Journal of National Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UP Minister Receives Death Threat on Phone, FIR Lodged

FREE PRESS 10 NATION INDORE | SATURDAY | FEBRUARY 10, 2018 UP minister receives death threat on phone, FIR lodged No death of shiksha mitras AGENCIES di Party legislator 7i(ay Police Aakash 9ulhari said (oined the *0P prior to the Allahabad Mishra. the matter as serious. ,e <%$= )ssembly polls after a ,e then asked his la yer said the police ere looking brief stint in the Congress. Uttar Pradesh /inister to file an FIR. for a Rajat 9esharwani. ,e survived a murderous 5and 6opal 6upta 5andi Details of the call and the 5andi! ho as earlier assault in <%$> hen bombs on Friday alleged that he phone number from hich ith the *ahu(an 'ama( ere lobbed at him, leaving during protests: UP govt received a death threat on the call as made have Party (BSP) and was a min- him critically ounded. his mobile phone! after been shared ith the police! ister in the /aya ati gov- ,is ife is the )llahabad hich police in )llahabad an aide told IANS. ernment bet een <%%=-$<! Mayor. AGENCIES tive Council Chairman lost their lives hile partic- sha mitras’ in recruitment lodged an FIR. Following the FI"! the po- Lucknow "amesh #adav to verify a ipating in protests and agi- e2amination of teachers.3 5andi! the /inister for lice raided the house of a list of $%& ‘shiksha mitras’ tations. The Samajwadi Party leg- 'tamp and "egistration! man ho o ns an automo- The Uttar Pradesh govern- ho had allegedly died dur- In reply! Basic Education islator! on a supplementary said he received the threat bile agency. -

Lucknow on Tuesday

4 + >6& *+./*?"& &(,/*?"&? #:* (;04 512152 6 528/ ,% .78298! ,$ 6'+(1 6 D$ 1B BA A 6A A 6 A0B0 1 0 B1 BAC 4B $*9 5< -( # @'*,""*+ ' ,,< +47 !"#$!% !""#$%%$%%% &'($&( **&&((* +',&*((& (& he rival factions of the LJP *'&, Twent in overdrive on ,&. Tuesday to gain the upper ('/ hand in keeping the party ! organisation on their side. & While Pashupati Kumar Paras- ' && led faction removed Chirag ((* %&'( Paswan from the post of the ((""&&& visibly upset Union Health president of the party, "&* *& Ministry on Tuesday warned Chirag hit back by expelling (*+ the public that as the country Paras and four other rebel MPs (* is dealing with highly trans- from the party. 0&((&/ missible variants now, con- While it’s clear that the tainment, social distancing anti-Chirag move has the bless- '' need to be more stringent. ing of both Bihar Chief + ' NITI Aayog member Dr Minister Nitish Kumar and ((* % VK Paul said at a Press con- the BJP leadership, Chirag is '" '& ference here that the hoping that Prime Minister '(* Government is keeping an eye Narendra Modi or Home *('*& on the Delta Plus variant, and Minister Amit Shah will come "*&,(& & the vaccination process in India to his rescue. ,&( & is expected to scale up. “After all Chirag batted for &($**'(.&, However, he warned peo- the BJP in the Bihar Assembly (& *(& ple should maintain social dis- polls, which spoiled his relation 1+'2% 2$&(. tancing. “Responsibility and with the BJP. Now it’s up to the , '( discipline are two important PM and the HM to find a solu- ""&& %* things for unlocking. Virus tion to this crisis. Chirag may *"&(&( transmission is very low right be isolated but he carries the */ now. -

AIRPORTS AUTHORITY of INDIA Press Brief PM Inaugurates New

AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA Press Brief PM inaugurates New Airport Complex at Bamrauli Airport, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh New Delhi, 17th December, 2018: A new airport complex at Bamrauli Airport in Prayagraj District of Uttar Pradesh was inaugurated on 16th December, 2018 by Hon’ble Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi. The inauguration took place in the august presence of Shri. Ram Naik, Hon’ble Governor of Uttar Pradesh; Shri Yogi Adityanath, Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Shri. Suresh Prabhu, Union Minister of Commerce and Industry and Civil Aviation; Shri. Keshav Prasad Maurya, Deputy Chief Minister, Uttar Pradesh, Shri. Sidharth Nath Singh, Minister of Medical & Health, Government of Uttar Pradesh, Shri Nand Gopal Gupta “Nandi”, Minister of Civil Aviation, Government of Uttar Pradesh, Dr. Mahendra Nath Pandey, Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), Shri. Shyama Charan Gupta, Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), Shri Nagendra Pratap Singh Patel, Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha). In his address, Hon`ble PM applauded the efforts made by Airports Authority of India to complete the project of New Airport Complex in record 11 months and congratulated Shri. Suresh Prabhu Hon`ble Minister of Civil Aviation and team of AAI. Airports Authority of India, under the supervision of the Ministry of Civil Aviation is committed to provide air connectivity and develop and upgrade airport infrastructure across the country. Due to the proactive measures being undertaken by the government, India is already one of the fastest growing civil aviation markets in the world. 1 The New Airport Complex of Bamrauli Airport has been developed by the Airports Authority of India, at a cost of Rs.164 Crores. -

Page-11.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU FRIDAY, APRIL 11, 2014 (PAGE 11) Shatrughan Sinha to get Many corporate honchos Modi slams Mamata, says she special award in IIFA MUMBAI, Apr 10: lag behind ‘netas’ in assets is playing vote bank politics Actor-turned-politician Shatrughan Sinha is all set to be hon- SILIGURI (WB), Apr 10: Delhi”. let the Congress open its NEW DELHI, Apr 10: tune of Rs 65 crore. Banker-turned-politician oured for his ‘outstanding contribution to Indian cinema’ at the “It’s been two years since the account in Bengal this time and However, Poonam Mahajan Sanyal, who is trying her luck Taking West Bengal Chief upcoming International Indian Film Acacdemy (IIFA) awards this new Government took charge, give BJP a chance to transform Lok Sabha candidates with (BJP candidate), daughter of on a AAP ticket from Mumbai year at Tampa Bay, Florida. Minister Mamata Banerjee head but have you seen any parivar- the state with “real develop- corporate background, such as late Pramod Mahajan, who is South, has wealth worth over Rs The 67-year-old veteran actor, who was last seen in Ram Gopal on, BJP’s prime ministerial can- tan? People have been cheated. ment”. Nandan Nilekani and Meera also fighting for the same con- 50 crore. The other two contest- Varma’s trilingual crime drama ‘Rakta Charitra’, will be awarded didate Narendra Modi today If you have a strong and pro- “You have given 60 years to Sanyal, may rank much above stituency has higher networth ants — Milind Deora for his illustrious career in the Hindi films for more than 45 years. -

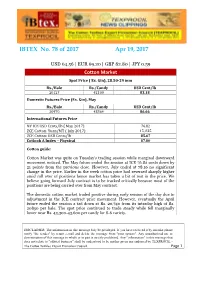

IBTEX No. 78 of 2017 Apr 19, 2017

IBTEX No. 78 of 2017 Apr 19, 2017 USD 64.56 | EUR 69.20 | GBP 82.80 | JPY 0.59 Cotton Market Spot Price ( Ex. Gin), 28.50-29 mm Rs./Bale Rs./Candy USD Cent/lb 20127 42100 83.18 Domestic Futures Price (Ex. Gin), May Rs./Bale Rs./Candy USD Cent/lb 20970 43864 86.66 International Futures Price NY ICE USD Cents/lb ( May 2017) 76.82 ZCE Cotton: Yuan/MT ( July 2017) 15, 835 ZCE Cotton: USD Cents/lb 85.67 Cotlook A Index – Physical 87.80 Cotton guide: Cotton Market was quite on Tuesday’s trading session while marginal downward movement noticed. The May future ended the session at ICE 76.82 cents down by 21 points from the previous close. However, July ended at 78.16 no significant change in the price. Earlier in the week cotton price had reversed sharply higher amid roll over of positions hence market has taken a bit of rest in the price. We believe going forward July contract is to be tracked critically because most of the positions are being carried over from May contract. The domestic cotton market traded positive during early session of the day due to adjustment in the ICE contract price movement. However, eventually the April future ended the session a tad down at Rs. 20,740 from its intraday high of Rs. 20850 per bale. The spot price continued to trade steady while fell marginally lower near Rs. 43,300-43,600 per candy for S-6 variety. DISCLAIMER: The information in this message July be privileged. -

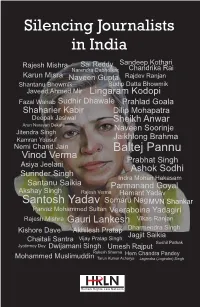

Silencing Journalists in India

In India, journalists have come under repeated attacks in the recent times. They have been killed, arrested, and Silencing Journalists wrongly implicated in many cases. There have been increasing number of criminal cases against journalists. in India Many media houses have seen their offices ransacked. It is sufficient to say that there have not been darker times for Sai Reddy Sandeep Kothari Rajesh Mishra Chandrika Rai journalists in India as it has been in the recent past and now. Narendra Dabholkar Karun Misra Rajdev Ranjan It is in this context that this compilation is brought out. This Naveen Gupta Shantanu Bhowmik Sudip Datta Bhowmik compilation brings out the stories of the journalists who Javeed Ahmed Mir Lingaram Kodopi have been arrested and killed for performing their duty. Attack on Journalists in India Fazal Wahab Sudhir Dhawale Prahlad Goala “Journalism can never be silent: That is its greatest virtue Shaharier Kabir Dilip Mohapatra and its greatest fault. It must speak, and speak immedi- Deepak Jasiwal Sheikh Anwar ately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph Arun Narayan Dekate Naveen Soorinje and the signs of horror are still in the air.” Jitendra Singh Kamran Yousuf Jaikhlong Brahma — Henry Anatole Grunwald, Nemi Chand Jain Baltej Pannu former Managing Editor, Time Magazine Vinod Verma Prabhat Singh “Journalism will kill you, but it will keep you alive while Asiya Jeelani Ashok Sodhi you’re at it.” Surinder Singh Indra Mohan Hakasam — Horace Greeley, Santanu Saikia Parmanand Goyal founder and editor of New -

Compendium of Adjudications 2010-2011

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Compendium of Adjudications (April 1, 2010 - March 31, 2011) New Delhi Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Compendium of Adjudications Contents Preface Index of Adjudications of the Council for -- 1 the Period April 1, 2010 – March 31, 2011 Adjudications of the Council -- 19 PREFACE While freedom of press is a right to be cherished at all costs, the most vociferous advocates of this right have also unequivocally advocated the case of balancing the right with the duty to report facts, clear and distinct from opinions and free from all biases and pre-conceived notions. For the Council the most potent instrument of furthering this cause is the medium of its adjudications on the complaints brought before it. The high number in the complaints being received by the Council is ample proof of the faith expressed by the mediamen and the public alike in the working, importance and need for a body like the Council at the helm of the fourth estate. I hope, the Compendium of Adjudications being published as usual in English as well as Hindi analyzing the adjudications rendered during the year will prove to be of interest to the readers and provide them the requisite information about the ethics expected of the press. G.N. Ray Chairman Press Council of India Index of Adjudications of the Council for the Period April 1, 2010 – March 31, 2011 S. Parties Date of No. Decision Harassment of Newsmen 1. Complaint of Shri Vakil Ahmed, Freelancer, Ghaziabad, July U.P. -

Merge May 13

2 All] Mukhtar Begum & Ors. Vs. Addl. District Judge and Anr. 585 ORIGINAL JURISDICTION stage it is giving rise to indiscriminate CIVIL SIDE and frequent petitions before this Court DATED: LUCKNOW 06.05.2013 and is leading this Court to colossal delay in administration of justice, in civil BEFORE cases, in out country. I am bound to THE HON'BLE SAAEED-UZ-ZAMAN SIDDIQI mention that the misinterpretation of J. law by the learned Appellate Court is gross of inexcusable error. Rent Control No.29 Of 2012 Case Law discussed: Mukhtar Begum & Ors ...Petitioner AIR 2001 SC 803; 1997 AIR (SC) 2399; Versus 2008(3) ARC 198; AIR 1999 Supreme Court Addl. District Judge and AnrRespondents 3029 Counsel for the Petitioner: (Delivered by Hon'ble Saeed-Uz-Zaman Sri Adnan Ahmad Siddiqi, J.) Sri Manish Misra 1. By means of this petition under Counsel for the Respondents: Article 226 of the Constitution of India, Manish Kumar the petitioners have prayed for issue a writ in the nature of certiorari quashing U.P. Urban Buildings & Regulation the impugned order dated 08.02.2012 (Letting and Rent Control) Act 1972- passed by Additional District Judge Section-27(7)- Application to release (Court No.7), Unnao in Rent Appeal No. accommodation by Land Lord on ground 1 of 2011. of bonafied need-allowed by Prescribed authority-during pendancy of rent control appeal-land lord died-application 2. Brief facts of the case are that the to substitute the heirs as well as petitioners filed P.A. Case No.14 of 2007 bonafide requirement of substituted land for release of accommodation under lord-rejection on ground after death of Section 21(1)(a) of the U.P. -

Silencing Journalists in India

Silencing Journalists in India Violation of Journalists’ Rights in India 2000-2018 Human Rights Law Network (HRLN) In Parnership with Press Club of India, Delhi Union of Journalists, Indian Women Press Corps, Brihmumbai Journalists Union, Mumbai Press Club and Media Studies Group 1 HUMAN RIGHTS LAW NETWORK • To protect fundamental human rights, increase access to basic resources for the marginalised communities, and eliminate discrimination. • To create a justice delivery system that is accessible, accountable, transparent, efficient and affordable, and works for the underprivileged. Raise the level of pro bono legal expertise for the poor to make the work uniformly competent as well as compassionate. • Professionally train a new generation of public interest lawyers and paralegals who are comfortable in the world of law as well as in social movements, and who learn from social movements to refine legal concepts and strategies. Silencing Journalists in India September 2019 © Socio Legal Information Centre* Research: Bonnie Smith, Sarita Ramamoorthy, Laxmi Murthy, Aditi Saxena Editor: Laxmi Murthy ISBN No.: 97881-934737-0-2 Design & Printed at: Shivam Sundram Published by Human Rights Law Network (Division of Socio-Legal Information Centre) 576, Masjid Road, Jangpura New Delhi - 110014 Phone No: +91-11-24374501 Disclaimer Text has been compiled from various sources for the purpose of this book. Photographs used are from those available on the internet through a generic search. *Any section of this volume may be reproduced without prior permission of HRLN for public interest purposes with appropriate acknowledgment. 2 3 INTRODUCTION: A Dangerous Profession Journalism in India has always been a difficult calling. -

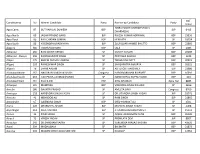

Constituency No Winner Candidate Party Runner-Up Candidate Party Votes GIRRAJ SINGH DHARMESH (G.S

Diff. Constituency No Winner Candidate Party Runner-up Candidate Party Votes GIRRAJ SINGH DHARMESH (G.S. Agra Cantt. 87 GUTIYARI LAL DUWESH BSP BJP 6415 DHARMESH) Agra North 89 JAGAN PRASAD GARG BJP RAJESH KUMAR AGRAWAL BSP 23356 Agra Rural 90 KALI CHARAN SUMAN BSP HEMLATA SP 18754 Agra South 88 YOGENDRA UPADHYAYA BJP ZULFIQUAR AHMED BHUTTO BSP 22960 Ajagara 385 TRIBHUVAN RAM BSP LALJI SP 2083 Akbarpur 281 RAM MURTI VERMA SP SANJAY KUMAR BSP 26286 Akbarpur - Raniya 206 RAMSWAROOP SINGH SP PRATIBHA SHUKLA BSP 1243 Alapur 279 BHEEM PRASAD SONKAR SP TRIBHUVAN DATT BSP 30023 Aliganj 103 RAMESHWAR SINGH SP SANGHMITRA MAURYA BSP 26021 Aligarh 76 ZAFAR AALAM SP ASHUTOSH VARSHNEY BJP 23086 Allahabad North 262 ANUGRAH NARAYAN SINGH Congress HARSHVARDHAN BAJPAYEE BSP 16092 Allahabad South 263 HAJI PARVEJ AHMAD (TANKI) SP NAND GOPAL GUPTA NANDI BSP 414 Allahabad West 261 POOJA PAL BSP ATIQ AHAMAD Apna Dal 8885 Amanpur 101 MAMTESH BSP VIRENDRA SINGH SOLANKI SP 3656 Amethi 186 GAYATRI PRASAD SP AMEETA SINH Congress 8760 Amritpur 193 NARENDRA SINGH YADAV SP DR. JITANDRA SINGH YADAV JKP 18971 Amroha 41 MEHBOOB ALI SP RAM SINGH BJP 21805 Anupshahr 67 GAJENDRA SINGH BSP SYED HIMAYAT ALI SP 3501 Aonla 126 DHARM PAL SINGH BJP MAHIPAL SINGH YADAV SP 4408 Arya Nagar 214 SALIL VISHNOI BJP JITENDRA BAHADUR SINGH SP 15411 Asmoli 32 PINKI SINGH SP AQEEL UR REHMAN KHAN BSP 26389 Atrauli 73 VIRESH YADAV SP PREMLATA DEVI JKP 8867 Atrauliya 343 DR.SANGRAM YADAV SP SURENDRA PRASAD MISHRA BSP 43620 Aurai 394 MADHUBALA SP BAIJNATH BSP 21873 Auraiya 204 MADAN SINGH ALIAS -

Regional Connectivity Scheme Giving the Much Needed UDAN to India Editorial

Vol. 01 | Issue 02 | Dec'17-Feb'18 REGIONAL CONNECTIVITY SCHEME Giving the much needed UDAN to India EDITORIAL AVIATION INDUSTRY GROWS WINGS Dr. BP Sharma Chairman and MD, PHL Dear Readers, Pawan Hans is proud to announce its participation in “Wings India 2018” to be held from March 8th to 11th in Hyderabad. It is one of the biggest international exhibition and conference on the Aviation sector, providing a congenial forum catering to the rapidly changing dynamics of the sector, focusing on new business acquisition, investments, policy formation B2B MoUs and promoting regional connectivity. The event is jointly, inter – alia, supported by Pawan Hans. Pawan Hans – A Mini Ratna” CPSE of Government of India under Ministry of Civil Aviation is a leader in providing helicopter services in India focusing on Off-shore, On-shore, Corporate helicopter services and providing services for promoting Heli Tourism, smart business solutions such as helicopter emergency services, disaster management, hot line washing of transmission lines, surveillance of law & order and the regional air connectivity. Pawan Hans has been instrumental in developing world class infrastructure for helicopter industry and has developed Nation’s First Integrated heliport in Delhi last year as one-point-solution for helicopter services, skill development and MRO services. Continue with the Vision of “New Look, New Horizon”, Pawan Hans is committed to provide its best in class helicopter services and expanding its horizons towards complementary services of providing better infrastructure, skill development, MRO, and consultancy services for overall growth of Helicopter Industry in India. Today) will provide you with in-depth view of the general aviation sector in the country andThis outside2nd edition country. -

Phd Chamber Bulletin

PHD CHAMBER BULLETIN Vol. XLIII No. 4 April - 2021 ` 25 PHD Chamber Bulletin | April 2021 1 2 PHD Chamber Bulletin | April 2021 PHD Chamber Bulletin | April 2021 3 4 PHD Chamber Bulletin | April 2021 Celebrating International Women’s Day 2021 Chief Guest, Ms. Anusuiya Uikey, Hon’ble Governor, Chhattisgarh MONTHLY NEWS BULLETIN OF PHD CHAMBER President Mr. Sanjay Aggarwal CONTENTS Senior Vice President Mr. Pradeep Multani PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 6 Vice President Mr. Saket Dalmia CHAMBER AT WORK 9 Editor: FOCUS STATES 59 Mr. Saurabh Sanyal Secretary General INTERFACE 81 HEADWAY Production Editor: Towards Inclusive Growth 89 Ms. Neelu Kapoor Economist & Bulletin Head COMMUNIQUE India Inc. is the official publication of PHD Chamber of Expressions 103 Commerce and Industry and any part of the publication may not be reproduced or transmitted in any other form in whole or in part without the written permission of the publishers. The MoUs 105 opinions and views expressed within this publication are not necessarily those of the publishers. The publishers regret that they cannot accept liability for errors or omissions in this issue. New Members 107 For further information and feedback, please contact: Media Buzz 108 PHD CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY PHD House, 4/2 Siri Institutional Area August Kranti Marg, New Delhi-110016 Phone : 91-11-26863801-04 Fax : 91-11-26855450 Email : [email protected] Website : www.phdcci.in PHD Chamber Bulletin | April 2021 5 MESSAGE President’s MESSAGE Friends, We hope this finds you all safe and well. The one thing that all of us have hoped and prayed for is an end to this relentless viral onslaught.