A Medieval Logboat from the River Conon | 307

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Chronology for Crannogs in North-East Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 147, Pp

Stratigos, M. J. and Noble, G. (2018) A new chronology for crannogs in north-east Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 147, pp. 147-173. (doi:10.9750/PSAS.147.1254) There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/165849/ Deposited on: 25 July 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk This is the peer-reviewed, revised but unedited version of an article which will be published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. A new chronology for crannogs in north-east Scotland Michael J Stratigos and Gordon Noble ABSTRACT This article presents the results of a programme of investigation which aimed to construct a more detailed understanding of the character and chronology of crannog occupation in north- east Scotland, targeting a series of sites across the region. The emerging pattern revealed through targeted fieldwork in the region shows broad similarities to the existing corpus of data from crannogs in other parts of the country. Crannogs in north-east Scotland now show evidence for origins in the Iron Age. Further radiocarbon evidence has emerged from crannogs in the region revealing occupation during the 9th–10th centuries ad, a period for which there is little other settlement evidence in the area. Additionally, excavated contexts dated to the 11th–12th centuries and historic records suggest that the tradition of crannog dwelling continued into the later medieval period. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

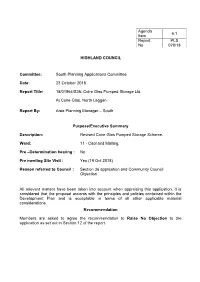

Item Report PLS No 078/18

Agenda 6.1 Item Report PLS No 078/18 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: South Planning Applications Committee Date: 23 October 2018 Report Title: 18/01564/S36: Coire Glas Pumped Storage Ltd. At Coire Glas, North Laggan. Report By: Area Planning Manager – South Purpose/Executive Summary Description: Revised Coire Glas Pumped Storage Scheme. Ward: 11 - Caol and Mallaig. Pre –Determination hearing : No Pre meeting Site Visit : Yes (19 Oct 2018) Reason referred to Council : Section 36 application and Community Council Objection All relevant matters have been taken into account when appraising this application. It is considered that the proposal accords with the principles and policies contained within the Development Plan and is acceptable in terms of all other applicable material considerations. Recommendation Members are asked to agree the recommendation to Raise No Objection to the application as set out in Section 12 of the report. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The proposal is a “national development” but not one advanced under Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997. The application requires determination by Scottish Ministers under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989. However, if approved, Scottish Ministers will issue a Direction under Section 57(2) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 that deemed planning permission be granted for the development. 1.2 Consent for abstraction, diversion and use of water for generating electricity is also being sought under Section 10(5) and Schedule 5 of the Electricity Act 1989. This requires licences from Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2006 (CAR). 1.3 The Council at this stage is a consultee on the proposed development. -

1 Minutes of Conon Bridge Community Council Meeting

MINUTES OF CONON BRIDGE COMMUNITY COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE STAFF ROOM AT BEN WYVIS PRIMARY SCHOOL ON WEDNESDAY 21 JUNE 2017 PRESENT Fiona MacKintosh (FM), Jim Attwood (JA), Alistair MacKintosh (AM), Jane Attwood (IJA), Councillor Margaret Paterson (part attendance), PC Kevin Taylor (Police Scotland) and one member of the public. WELCOME Fiona MacKintosh welcomed everyone to the meeting. 1. Apologies Hazel Bushell and Councillor Alistair MacKinnon. Councillor Graham Mackenzie by email at 19.20 2. Police Report PC Kevin Taylor opened by advising the meeting that he had only been in the area since February 2017 and had been in the police force for the last ten years. He hoped that he would be able to come to future meetings but that depended on operational duties and he would endeavour to meet the expectations of the community. Although he had only been in the area for a few months he could already see that there were two main problems within the local area, these being anti-social behaviour and neighbour disputes. Two offences had been reported to the Procurator Fiscal this month and PC Taylor hoped that these would be dealt with robustly. He is working very closely with the housing associations and The Highland Council in trying to resolve the ongoing neighbour situations. Also of note were various incidents involving vandalism and one instance of shoplifting by a child. This has been reported to the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA). Currently the Conon Bridge area is seeing an increase in the level of reported anti-social behaviour by youths. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

The Edinburgh Union Canal Strategy

The Edinburgh Union Canal Strategy DECEMBER 2011 The Edinburgh Union Canal Strategy The Edinburgh Union Canal Strategy Contents THE EDINBURGH UNION CANAL STRATEGY 3 ince its re-birth as part of the Millennium Link Project the Union Canal has come a long way from a derelict CONTENTS 3 S backwater to become one of Edinburgh’s most important heritage, recreational and community assets. The BACKGROUND 4 Union Canal is now enjoyed on a daily basis by people from across the city and beyond for a variety of uses such as boating, rowing, walking, cycling and fi shing. THE EDINBURGH UNION CANAL STRATEGY KEY AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 5 The Union Canal is also a focus for new development, The City of Edinburgh Council (CEC) and British Current Context 7 particularly at Fountainbridge, for new canal boat Waterways Scotland (BWS) have prepared this strategy SCOTLAND’S CANALS 9 moorings and marinas and for canal-focused for the Union Canal within the Edinburgh area to THE UNION CANAL IN EDINBURGH 9 community activities. However, as the canal is guide its development and to promote a vision of the HISTORY AND HERITAGE 10 developed, it must also be protected and its potential place we wish the Union Canal to be. PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT 11 maximised for the for the benefi t of the wider ENVIRONMENT AND BIODIVERSITY 12 community and environment. MOVEMENT AND CONNECTIVITY 13 COMMUNITY AND TOURISM 14 The Strategy 15 “The Union Canal is one of Edinburgh’s hidden gems. We hope this Strategy OPPORTUNITY 1 - ACCESS TO THE UNION CANAL 16 will allow more of our citizens to appreciate and benefi t from its beauty as OPPORTUNITY 2 - WATERWAY, DEVELOPMENT AND ENVIRONMENT 18 well as the economic development potential it provides.” OPPORTUNITY 3 - COMMUNITY, RECREATION AND TOURISM 20 Councillor Tim McKay, Edinburgh Canal Champion OPPORTUNITY 4 - INFRASTRUCTURE, DRAINAGE, CLIMATE CHANGE 22 The Canal Hubs 23 “The publication of the new Edinburgh Canal Strategy is a major milestone in the renaissance of the RATHO 26 two hundred year old Union Canal. -

Crannogs — These Small Man-Made Islands

PART I — INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Islands attract attention.They sharpen people’s perceptions and create a tension in the landscape. Islands as symbols often create wish-images in the mind, sometimes drawing on the regenerative symbolism of water. This book is not about natural islands, nor is it really about crannogs — these small man-made islands. It is about the people who have used and lived on these crannogs over time.The tradition of island-building seems to have fairly deep roots, perhaps even going back to the Mesolithic, but the traces are not unambiguous.While crannogs in most cases have been understood in utilitarian terms as defended settlements and workshops for the wealthier parts of society, or as fishing platforms, this is not the whole story.I am interested in learning more about them than this.There are many other ways to defend property than to build islands, and there are many easier ways to fish. In this book I would like to explore why island-building made sense to people at different times. I also want to consider how the use of islands affects the way people perceive themselves and their landscape, in line with much contemporary interpretative archaeology,and how people have drawn on the landscape to create and maintain long-term social institutions as well as to bring about change. The book covers a long time-period, from the Mesolithic to the present. However, the geographical scope is narrow. It focuses on the region around Lough Gara in the north-west of Ireland and is built on substantial fieldwork in this area. -

VIKING AGE SILVER HOARDS in IRELAND Regional Trade and Cultural Identity

VIKING AGE SILVER HOARDS IN IRELAND Regional trade and cultural identity Linn Marie Krogsrud Master’s thesis in Archaeology Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo Autumn 2008 Cover image: Unlocalized mixed hoard from Antrim c. AD 910 (after Sheehan 2001:54; with courtesy of Ulster Museum, Belfast) Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my supervisor Lotte Hedeager for her constructive support and optimism. She has made this thesis seem, at times, almost easy to write. Secondly, my other supervisor Stephen Harrison deserves much credit for all his help: his knowledge of Viking Age Ireland and supply of hand-outs have been invaluable. A warm thank you also goes to Julie Lund for stepping in for Lotte. John Sheehan and Charles Doherty willingly shared their ideas and off-prints with me, for which I am very grateful. I would also like to thank Dr. Colmán Etchingham for his bibliography tips, and Unn Pedersen for providing me with the article on Woodstown. A special thank you goes to Zanette T. Glørstad for leading me to the Viking Age silver hoards and for supplying me with one of her articles. Many thanks go to Herdis Hølleland and Tale Marthe Dæhlen for proof-reading the final draft of the thesis. All the students at Blindernveien 11 deserve thanks for all the non-academic conversations in the lunch room, especially Anna Alexandra Myrer, Grethe Móell Pedersen, Gunnhild Wentzel, Maria Valum, Annette Solberg and Elise Naumann. Irish transplant Joanne Ó Sullivan also deserves credit. At last, I would like to thank my family and my good friends Suzanne Leidl and Anja Steinsland for all their support. -

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar Introduction The Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland from August 14-26, 2014, was organized for Clan Dunbar members with the primary objective to visit sites associated with the Dunbar family history in Scotland. This Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland focused on Dunbar family history at sites in southeast Scotland around Dunbar town and Dunbar Castle, and in the northern highlands and Moray. Lyle Dunbar, a Clan Dunbar member from San Diego, CA, participated in both the 2014 tour, as well as a previous Clan Dunbar 2009 Tour of Scotland, which focused on the Dunbar family history in the southern border regions of Scotland, the northern border regions of England, the Isle of Mann, and the areas in southeast Scotland around the town of Dunbar and Dunbar Castle. The research from the 2009 trip was included in Lyle Dunbar’s book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part I-The Earls of Dunbar, recently published in May, 2014. Part I documented the early Dunbar family history associated with the Earls of Dunbar from the founding of the earldom in 1072, through the forfeiture of the earldom forced by King James I of Scotland in 1435. Lyle Dunbar is in the process of completing a second installment of the book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part II- After the Fall, which will document the history of the Dunbar family in Scotland after the fall of the earldom of Dunbar in 1435, through the mid-1700s, when many Scots, including his ancestors, left Scotland for America. -

Great Glen Way

Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Great Glen Way The Great Glen Way runs 73 miles following the Great Glen from Fort William on the Atlantic west coast to Inverness on the North Sea. This is a dramatic, but pleasantly relaxed, Scottish Coast to Coast route following one of the Highlands most celebrated glens. From Loch Linnhe on the Atlantic coast the route follows canal towpaths, loch shore paths and forestry tracks to reach Inverness, capital of the Highlands. This is a relatively easy, low level route providing great views of the Lochs of the Great Glen and fine panoramas of the surrounding Highlands. With good waymarking, this trail is a good introduction to the Scottish Highlands. To book please visit www.mickledore.co.uk or call +44 (0) 17687 72335 1166 1 Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Summary be rougher or muddy, so good footwear essential. the riverside path and canal towpath to the highland Why do this walk? village of Gairlochy, at the foot of Loch Lochy. • Walk from coast to coast through the Scottish How Much Up & Down? Amazingly little considering Gairlochy - South Laggan: The shores of highlands, on well made paths without too much the size of the surrounding mountains! Some Loch Lochy ascent. short steep ascents and a longer climb of 300m to This 13 mile section follows the northern • The Caledonian Canal provides an interesting Blackfold on the final day. bank of Loch Lochy for its entire length. It is backdrop and historical interest along much of characterised by fairly easy walking on forestry the route. -

The A9-A96 Inshes to Smithton CPO Schedule

THE A9 and A96 TRUNK ROADS (INSHES TO SMITHTON) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 201[ ] Made 201[ ] The Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 and the Acquisition of Land (Authorisation Procedure) (Scotland) Act 1947. The Scottish Ministers (hereinafter referred to as “the acquiring authority”) in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 103 to 108 inclusive as read with section 110(2) of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 hereby make the following compulsory purchase order- 1. This Order may be cited as the A9 and A96 Trunk Roads (Inshes to Smithton) Compulsory Purchase Order 201[ ]. 2. Subject to the provisions of this Order, the acquiring authority are hereby authorised to purchase compulsorily for the purpose of improving the A96 Aberdeen – Inverness Trunk Road and the M9/A9 Edinburgh – Stirling – Thurso Trunk Road by constructing the new Inshes to Smithton Road between Inshes in the vicinity of Culloden, Inverness-shire and Smithton Roundabout, Inverness, the land and servitude rights which are described in the Schedule hereto and are numbered and shown delineated in red and coloured pink and blue respectively, on the map signed with reference to this Order and marked “Map referred to in the A9 and A96 Trunk Roads (Inshes to Smithton) Compulsory Purchase Order 201[ ]”. 3. In relation to the foregoing purchase section 70 of the Railways Clauses Consolidation (Scotland) Act 1845 and sections 71 to 78 of that Act as originally enacted and not as amended for certain purposes by section 15 of the Mines (Working Facilities and Support) Act 1923 are hereby incorporated with the enactment under which the said purchase is authorised, subject to the modifications that references in the said sections to the company shall be construed as references to the acquiring authority and references to the railway or works shall be construed as references to the land authorised to be purchased and any building or works constructed or to be constructed thereon. -

Openness & Accountability Mailing List

Openness & Accountability Mailing List AINA Amateur Rowing Association Anglers Conservation Association APCO Association of Waterway Cruising Clubs British Boating Federation British Canoe Union British Marine Federation Canal & Boat Builder’s Association CCPR Commercial Boat Operators Association Community Boats Association Country Landowners Association Cyclist’s Touring Club Historic Narrow Boat Owners Club Inland Waterways Association IWAAC Local Government Association NAHFAC National Association of Boat Owners National Community Boats Association National Federation of Anglers Parliamentary Waterways Group Rambler’s Association The Yacht Harbour Association Residential Boat Owner’s Association Royal Yachting Association Southern Canals Association Steam Boat Association Thames Boating Trades Association Thames Traditional Boat Society The Barge Association Upper Avon Navigation Trust Wooden Canal Boat Society ABSE AINA Amber Valley Borough Council Ash Tree Boat Club Ashby Canal Association Ashby Canal Trust Association of Canal Enterprises Aylesbury Canal Society 1 Aylesbury Vale District Council B&MK Trust Barnsley, Dearne & & Dover Canal Trust Barnet Borough Council Basingstoke Canal Authority Basingstoke Canal Authority Basingstoke Canal Authority Bassetlaw District Council Bath North East Somerset Council Bedford & Milton Keynes Waterway Trust Bedford Rivers Users Group Bedfordshire County Council Birmingham City Council Boat Museum Society Chair Bolton Metropolitan Council Borough of Milton Keynes Brent Council Bridge 19-40