Davenport, J. Appositional Black Aesthetics FINAL1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Mixed-Race Women in the United States During the Early Twentieth Century

Of Double-Blooded Birth: A History of Mixed-Race Women in the United States during the Early Twentieth Century Jemma Grace Carter Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in American Studies at the University of East Anglia, School of Arts, Media, and American Studies January 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Often homogenised into broader narratives of African-American history, the historical experience of mixed-race women of black-white descent forms the central research focus of this thesis. Examining the lives of such women offers a valuable insight into how notions of race, class, gender and physical aesthetics were understood, articulated and negotiated throughout the United States during the early-twentieth century. Through an analysis of wide-ranging primary source material, from letters, diaries and autobiographies to advertisements, artwork and unpublished poetry, this thesis provides an interdisciplinary contribution to the field of Critical Mixed Race Studies, and African- American history. It builds on existing interpretations of the Harlem Renaissance by considering the significance of mixed-racial heritage on the formation of literature produced by key individuals over the period. Moreover, this research reveals that many of the visual and literary sources typically studied in isolation in fact informed one another, and had a profound impact on how factors such as beauty, citizenship, and respectability intersected, and specifically influenced the lives of mixed-race women. -

Lantern Slides SP 0025

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 What are Finding Aids? Finding aids are narrative guides to archival collections created by the repository to describe the contents of the material. They often provide much more detailed information than can be found in individual catalog records. Contents of finding aids often include short biographies or histories, processing notes, information about the size, scope, and material types included in the collection, guidance on how to navigate the collection, and an index to box and folder contents. What are Legacy Finding Aids? The following document is a legacy finding aid – a guide which has not been updated recently. Information may be outdated, such as the Historical Society’s contact information or exact box numbers for contents’ location within the collection. Legacy finding aids are a product of their times; language and terms may not reflect the Historical Society’s commitment to culturally sensitive and anti-racist language. This guide is provided in “as is” condition for immediate use by the public. This file will be replaced with an updated version when available. To learn more, please Visit DCHistory.org Email the Kiplinger Research Library at [email protected] (preferred) Call the Kiplinger Research Library at 202-516-1363 ext. 302 The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation’s capital. Founded in 1894, it serves a diverse audience through its collections, public programs, exhibits, and publications. THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Oral History Interview with Archibald Motley, 1978 Jan. 23-1979 Mar. 1

Oral history interview with Archibald Motley, 1978 Jan. 23-1979 Mar. 1 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview DB: Dennis Barrie AM: Archibald Motley DB: Today is January 23, 1978. I am here in the home of Archibald Motley, a Chicago artist. My name is Dennis Barrie. Today we're going to talk about Mr. Motley's life and career. I thought I'd start by asking you to give us a little background about your family, about the family you came from. AM: Well, I'd like to start first with my two grandmothers, the one on the side of my father and the one on the side of my mother, maternal and paternal. The grandmother that I painted was on the paternal side. She was the one I think I told you I cared so very, very much about. She was a very kind person, a nice person, she had so much patience. I've always hoped that I could continue her teaching that she taught me when I was young. I think I've done a pretty fair job of it because I still have the patience of Job not only in my work but I think I've it with people. Now I'm going over to the other grandmother. She was a pygmy from British East Africa, a little bit of a person, very small, she was about four feet, eight or nine inches. -

A Finding Aid to the Eldzier Cortor Papers, Circa 1930S-2015, Bulk 1972-2015 in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Eldzier Cortor papers, circa 1930s-2015, bulk 1972-2015 in the Archives of American Art Justin Brancato and Rayna Andrews Funding for the 2017 processing of this collection was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation. 2017 December 28 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1947-2012............................................................. 5 Series 2: Correspondence, 1970-2015.................................................................... 6 Series 3: Professional Files, -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

PROGRAM SESSIONS Madison Suite, 2Nd Floor, Hilton New York Chairs: Karen K

Wednesday the Afterlife of Cubism PROGrAM SeSSIONS Madison Suite, 2nd Floor, Hilton New York Chairs: Karen K. Butler, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Wednesday, February 9 Washington University in St. Louis; Paul Galvez, University of Texas, Dallas 7:30–9:00 AM European Cubism and Parisian Exceptionalism: The Cubist Art Historians Interested in Pedagogy and Technology Epoch Revisited business Meeting David Cottington, Kingston University, London Gibson Room, 2nd Floor Reading Juan Gris Harry Cooper, National Gallery of Art Wednesday, February 9 At War with Abstraction: Léger’s Cubism in the 1920s Megan Heuer, Princeton University 9:30 AM–12:00 PM Sonia Delaunay-Terk and the Culture of Cubism exhibiting the renaissance, 1850–1950 Alexandra Schwartz, Montclair Art Museum Clinton Suite, 2nd Floor, Hilton New York The Beholder before the Picture: Miró after Cubism Chairs: Cristelle Baskins, Tufts University; Alan Chong, Asian Charles Palermo, College of William and Mary Civilizations Museum World’s Fairs and the Renaissance Revival in Furniture, 1851–1878 Series and Sequence: the fine Art print folio and David Raizman, Drexel University Artist’s book as Sites of inquiry Exhibiting Spain at the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 Petit Trianon, 3rd Floor, Hilton New York M. Elizabeth Boone, University of Alberta Chair: Paul Coldwell, University of the Arts London The Rétrospective and the Renaissance: Changing Views of the Past Reading and Repetition in Henri Matisse’s Livres d’artiste at the Paris Expositions Universelles Kathryn Brown, Tilburg University Virginia Brilliant, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Hey There, Kitty-Cat: Thinking through Seriality in Warhol’s Early The Italian Exhibition at Burlington House Artist’s Books Andrée Hayum, Fordham University Emerita Lucy Mulroney, University of Rochester Falling Apart: Fred Sandback at the Kunstraum Munich Edward A. -

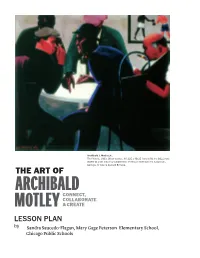

Motley-Lesson-The-Plotters.Pdf

Archibald J. Motley Jr., The Plotters, 1933. Oil on canvas, 36.125 x 40.25 inches (91.8 x 102.2 cm). Walter O. and Linda Evans Collection of African American Art, Savannah, Georgia. © Valerie Gerrard Browne. THE ART OF ARCHIBALD CONNECT, COLLABORATE MOTLEY & CREATE: LESSON PLAN by Sandra Saucedo-Flagan, Mary Gage Peterson Elementary School, Chicago Public Schools Summary of lesson plan In this unit for 4th grade language arts, students will study different people of past and modern history that are known to be “revolutionaries.” The term “revolutionary” follows Merriam Webster’s definition as someone who “participated in or brought about a major or fundamental change.” As students study various worldly figures, they will answer the question, “What makes this person a revolutionary?” Using text references and their own inferences based on what information they have gathered, students will be able to answer this question. Students will also explore the big idea of persever- ance; namely how the revolutionaries overcome conflict and stay true to their convictions. Big Idea • A theme is a message that the author/artist wants readers/viewers to understand about people, life, and the world in which we live. • Authors/Artists make decisions about topics in order to communicate ideas and experiences. • Perseverance has many qualities including fear, hard work, discipline, commitments, failure, and passion. Interpretations of a text involve linking information across parts of a text and determining importance of the information presented. • References from texts provide evidence to support conclusions drawn about the message, the information presented, and/or the author’s/artist’s perspective. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Carrie Mae Weems

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Carrie Mae Weems Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Weems, Carrie Mae, 1953- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Carrie Mae Weems, Dates: September 10, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:57:58). Description: Abstract: Visual artist Carrie Mae Weems (1953 - ) was an award-winning folkloric artist represented in public and private collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and The Art Institute of Chicago. Weems was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 10, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_175 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Visual artist Carrie Mae Weems was born on April 20, 1953 in Portland, Oregon to Myrlie and Carrie Weems. Weems graduated from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia with her B.F.A. degree in 1981, and received her M.F.A. degree in photography from the University of California, San Diego in 1984. From 1984 to 1987, she participated in the graduate program in folklore at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1984, Weems completed her first collection of photographs, text, and spoken word entitled, Family Pictures and Stories. Her next photographic series, Ain't Jokin', was completed in 1988. She went on to produce American Icons in 1989, and Colored People and the Kitchen Table Series in 1990. -

Fryd, “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 1, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Vivian Green Fryd, “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 1, no. 2 (Fall 2015), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1527. Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist Vivien Green Fryd, Professor, Vanderbilt University Richard Powell, editor Exh. cat. Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2014; 192 pp.; 69 b/w and 88 color ills.; $30.17 (paper); ISBN: 9780938989370 Exhibition schedule: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, January 30-May 11, 2014; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, TX, June 14- September 7, 2014; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, October 19, 2014- February 1, 2015; Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL, March 6-August 31, 2015; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, Fall 2015 Organized and edited by the art historian Richard Powell, this exhibition and its accompanying catalogue mark the first full-scale retrospective in twenty years of the paintings by Archibald J. Motley, Jr. (1891-1981).1 Consisting of forty-two works created between 1919 and 1961, the exhibition and richly illustrated catalogue highlight the Harlem Renaissance artist’s vividly colored portraits, street scenes, and social gatherings of African Americans living in Chicago. Motley’s bold, strident colors, exaggerated gestures and facial expressions, flattened spaces, and compressed figures merge together in public spaces with journalpanorama.org • [email protected] • ahaaonline.org Vivien Green Fryd, “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” Page 2 neon lights and signs, participating in modern day leisure activities. This includes nightclubs and cabaret shows, concerts and plays, exhibitions and movie screenings. -

Security Council Provisional Asdf Seventieth Year 7389Th Meeting Monday, 23 February 2015, 10 A.M

United Nations S/ PV.7389 Security Council Provisional asdf Seventieth year 7389th meeting Monday, 23 February 2015, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Wang Yi/Mr. Wang Min/Mr. Cai Weiming . ......... (China) Members: Angola. Mr. Augusto Chad .......................................... Mr. Mangaral Chile .......................................... Mr. Barros Melet France ......................................... Mr. Delattre Jordan ......................................... Mrs. Kawar Lithuania . ...................................... Mr. Linkevičius Malaysia ....................................... Mr. Aman New Zealand .................................... Mr. McCully Nigeria . ........................................ Mr. Wali Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Lavrov Spain .......................................... Mr. Ybañez United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ... Sir Mark Lyall Grant United States of America . .......................... Ms. Power Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) ................... Mrs. Rodríguez Gómez Agenda Maintenance of international peace and security Reflect on history, reaffirm the strong commitment to the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations Letter dated 3 February 2015 from the Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General (S/2015/87) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official -

Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017

Description of document: Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017 Requested date: 18-June-2017 Released date: 03-October-2018 Posted date: 15-October-2018 Source of document: Records Request Assistant General Counsel Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel MRC 012 PO Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 Fax: 202-357-4310 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 0 Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel VIA US MAIL October 3, 2018 RE: Your Request for Smithsonian Records (request number 48730) This responds to your request, dated June 18, 2017 and received in this Office on June 27, 2017, for "a copy of the meeting minutes from the Hirschhorn (sic) Museum Board of Trustees, during the time period 2013 to present." The Smithsonian responds to requests for records in accordance with Smithsonian Directive 807 - Requests for Smithsonian Institution Information (SD 807) and applies a presumption of disclosure when processing such requests. -

Commemorative Works Catalog

DRAFT Commemorative Works by Proposed Theme for Public Comment February 18, 2010 Note: This database is part of a joint study, Washington as Commemoration, by the National Capital Planning Commission and the National Park Service. Contact Lucy Kempf (NCPC) for more information: 202-482-7257 or [email protected]. CURRENT DATABASE This DRAFT working database includes major and many minor statues, monuments, memorials, plaques, landscapes, and gardens located on federal land in Washington, DC. Most are located on National Park Service lands and were established by separate acts of Congress. The authorization law is available upon request. The database can be mapped in GIS for spatial analysis. Many other works contribute to the capital's commemorative landscape. A Supplementary Database, found at the end of this list, includes selected works: -- Within interior courtyards of federal buildings; -- On federal land in the National Capital Region; -- Within cemeteries; -- On District of Columbia lands, private land, and land outside of embassies; -- On land belonging to universities and religious institutions -- That were authorized but never built Explanation of Database Fields: A. Lists the subject of commemoration (person, event, group, concept, etc.) and the title of the work. Alphabetized by Major Themes ("Achievement…", "America…," etc.). B. Provides address or other location information, such as building or park name. C. Descriptions of subject may include details surrounding the commemorated event or the contributions of the group or individual being commemorated. The purpose may include information about why the commemoration was established, such as a symbolic gesture or event. D. Identifies the type of land where the commemoration is located such as public, private, religious, academic; federal/local; and management agency.