SENATE Official Committee Hansard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

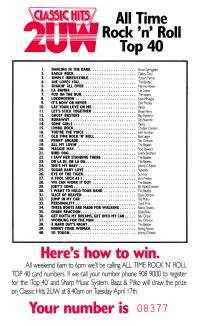

2UW All Time Rock'n'roll Top 40

All Time Rock 'n' Roll Top 40 I. DANCING IN THE DARK Bruce Springsteen 2. EAGLE ROCK Daddy Cool 3. SIMPLY IRRESISTIBLE Robert Palmer 4. SHE LOVES YOU The Beatles 5. SHAKIN' ALL OVER Normie Rowe 6. LA BAMBA Los Lobos 7. FOX ON THE RUN The Sweet 8. LOCOMOTION Kylie Minogue 9. IT'S NOW OR NEVER Elvis Presley 0. LAY YOUR LOVE ON ME Racey I. LET'S STICK TOGETHER Bryan Ferry 2. GHOST BUSTERS Ray Parker Jr 3. RUNAWAY Del Shannon 4. SOME GIRLS Racey S. LIMBO ROCK Chubby Checker 6. YOU'RE THE VOICE John Farnham 7. OLD TIME ROCK 'N' ROLL Bob Seger 8. PENNY ARCADE Roy Orbison 9. ALL MY LOVIN' The Beatles 20. MAGGIE MAY Rod Stewart 21. BIRD DOG Everly Brothers 22. I SAW HER STANDING THERE The Beatles 23. OB LA DI, OB LA DA The Beatles 24. SHE'S MY BABY Johnny O'Keefe 25. SUGAR BABY LOVE Rubettes 26. EYE OF THE TIGER Survivor 27. A FOOL SUCH AS I Elvis Presley 28. WE CAN WORK IT OUT The Beatles 29. JOEY'S SONG Bill Haley/Comets 30. I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND The Beatles 31. SLICE OF HEAVEN Dave Dobbyn 32. JUMP IN MY CAR Ted Mulry 33. PERSONALITY . Lloyd Price 34. THESE BOOTS ARE MADE FOR WALKING Nancy Sinatra 35. CHAIN REACTION Diana Ross 36. GET OUTTA MY DREAMS, GET INTO MY CAR Billy Ocean 37. WORKING FOR THE MAN Roy Orbison 38. A HARD DAY'S NIGHT The Beatles 39. HONKY TONK WOMAN Rolling Stones 40. -

Headline Act Normie Rowe AM

Headline Act Normie Rowe AM Melbourne-born Normie Rowe is one of the most recognised names in Australian music. He released a string of Australian pop hits that kept him at the top of the Australian charts and made him the most popular solo performer of the mid- 1960s. Rowe's double-sided hit "Que Sera Sera" / "Shakin' All Over" was one of the most successful Australian singles of the 1960s. Between 1965 and 1967 Rowe was Australia's most popular male star but his career was cut short when he was drafted for compulsory National Service when his name came up in first 1968 intake. In 1987, Normie landed the lead role of Jean Valjean in the musical ‘Les Miserables’, which he played to great acclaim in over 600 performances. He then appeared in leading roles in a string of musicals, including ‘Annie’, ‘Chess’, ‘Evita’, ‘Cyrano’, ‘Get Happy’ and ‘Oklahoma’. In 2002 he stole the show with his performances of ‘Que Sera, Sera’ and ‘Shakin' All Over’ on the hugely successful ‘Long Way To The Top’ concert series which played to 160,000 people across Australia and became a hit CD/DVD and national television broadcast. In 2005 Normie Rowe was inducted into the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) Hall of Fame. In that year he was also recognized by the Australian War Memorial as a National Hero, alongside the likes of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith, Vivien Bullwinkle, Keith Miller, Chips Rafferty and 45 other heroes of Australia. Normie Rowe has become a leading advocate and spokesman for the Vietnam Veterans and in 1987 and 1992 he was instrumental as a member of the National Committees for the Vietnam Veterans Welcome Home Parade and the Vietnam National Memorial Dedication. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Civic Hall Roster

PERFORMERS, SPEAKERS & EVENTS AT CIVIC HALL 1956 – 2002 * List with sources of information * Queries over conflicting or uncertain dates 60/40 Dance, 1 June 2002: [Source: Typed playlist, Graeme Vendy] 60/40 Dances held over long period, featuring local and nationally significant performers ACDC - Giant Dose of Rock and Roll Tour Jan 14 1977 Larry Adler (harmonica), ABC Celebrity Concert Series, 1 November 1961 Laurie Allan - guitar accompanied World Champion boxer Lionel Rose, 1970 The Angels 1990 [Courier article July 3, 2010. Graeme Vendy] Archbishop of Canterbury. Concelebrated Mass, 1985. 1 May Winifred Atwell, (pianist) 29 April 1965; The Winifred Atwell Show – 16 March 1962; 1972 [Source: Mary Kelly programmes] Australian Crawl, 1982, December 18, 1983 [Source: Graeme Plenter photo] AZIO, 1 December, 2013 (outside steps) Ballarat College Centenary Celebrity Concert & Official Opening 3 July, 1964. [Programme, Collection BCC – Heather Jackson Archivist] Ballarat College Centenary Dinner 4 July, 1964. [Programme & photos, Collection BCC] Ballarat & Clarendon College, Speech Night, 1999: [Source: Program, Graeme Vendy] Ballarat Choral Society & Ballarat Symphony Orchestra, Handel’s Messiah, December 1961 – 1965. 18 Dec 1963, 16 Dec 1964, 15 Dec 1965 [Source: programs donated by Norm Newey] Ballarat City Choir 1965, Ballarat Civic Male Choir 1956, 1965, 1977 Ballarat Ladies’ Pipe Band & National Dancing Class Ballarat Light Opera Company, 1957, 1959, 1960 Ballarat Teachers’ College Annual Graduation Ceremony, 9 Dec 1960. Speaker Prof Z. Cowan, Barrister-at-Law [Source: Invitation to Mrs Hathaway. Coll. Merle Hathaway] Ballarat Symphony Orchestra, Premier Orchestral Concert, with Leslie Miers (pianist) 1965 Ballarat Symphony Orchestra “Music to Enjoy” concert, 13 Aug 1967, cond. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Dylan Review, Summer 2020

DYLAN REVIEW, SUMMER 2020 MASTHEAD CO-EDITORS Raphael Falco, University of Maryland, Baltimore County Paul Haney, University of Massachusetts, Boston Lisa O'Neill Sanders, Founder DR, Saint Peter's University Shelby Nathanson, Digital Editor Nicole Font, Assistant to the Editors EDITORIAL BOARD Mitch Blank, New York City Michael Gilmour, Providence University College (Canada) Nina Goss, Fordham University Charles O. Hartman, Connecticut College Jonathan Hodgers, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Reginio, Alfred University Christopher Rollason, Luxembourg Richard Thomas, Harvard University Dylan Review 2.1 (Summer 2020) DYLAN REVIEW, SUMMER 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL TOPIC: CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS………………….……………………………..2 REVIEWS Charles O. Hartman, Rough and Rowdy Ways: Containing History….………....3 John Hunt and Tim Hunt, Travelin’ Thru ...…………………..……………………....16 THE DYLANISTA………………………………………………………………………………28 ARTICLES Richard F. Thomas, “And I Crossed the Rubicon”: Another Classical Dylan....35 Graley Herren, Young Goodman Dylan: Chronicles at the Crossroads..……..65 SONG CORNER Anne Margaret Daniel, “Murder Most Foul”….…………………………………….83 INTERVIEWS Mark Davidson…………………………………………………………………………... 95 LETTERS………………………………………………………………………………….…...106 CONTRIBUTORS…………………………………………………………………….………107 BOOKS RECEIVED………………………………………………………………………….109 BOB DYLAN LYRICS, COPYRIGHT INFORMATION……………………………………110 1 Dylan Review 2.1 (Summer 2020) SPECIAL TOPIC: CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS THE COPS DON’T NEED YOU AND MAN THEY EXPECT THE SAME For the next issue of the Dylan Review, Winter 2.2, the Editors invite articles and Song Corner essays on the special topic of political authority and race in Dylan’s work. Up on Housing Project Hill It’s either fortune or fame You must pick one or the other Though neither of them are to be what they claim If you’re lookin’ to get silly You better go back to from where you came Because the cops don’t need you And man they expect the same This familiar stanza from “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” sets the tenor for the Editors’ special topic. -

Sunrise Playlist Kalenderwoche 05 / 2002

JAM/FM – Sunrise Montag-Freitag 6:00-10:00 Uhr Mit Jörg Wachsmuth Playlist KW 05-2002 Montag, 28. Januar 2002 Zeit Interpret Titel Label 6:05 Aaliyah More Than A Woman Blackground 6:09 Ginuwine Differences Epic 6:15 St. Lunatics Groovin Tonight Universal 6:20 Nelly #1 (Radio) Virgin 6:23 Jocelyn Brown Somebody Else´s Guy Target 6:26 Princess Superstar Bad Babysitter Rapster 6:33 Somethin For The People feat Now U Wanna Warner Xzibit 6:37 Gangstarr You Know My Steez Cooltempo 6:44 Faith Evans You Gets No Love Arista 6:48 Eric Sermon I´m Hot J-Records 6:54 AZ feat SWV Hey AZ Cooltempo 6:58 Foxy Brown Hot Spot DefJam Zeit Interpret Titel Label 7:05 Mary J Blige Family Affair MCA 7:09 Busta Rhymes Break Y Neck J-Records 7:15 Ol´Dirty Bastard Sussudio Warner 7:20 Jaheim feat. Next Anything Warner 7:24 Samy Deluxe Weck Mich Auf EMI 7:26 A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It Columbia 7:33 Nas Got Ur Self A... Columbia 7:37 DrDre & Snoop Dogg The Wash Aftermath 7:44 Cypress Hill Low Rider Columbia 7:47 Mystikal Bouncin´Back Jive 7:54 Mariah Carey Honey (SoSoDef) Columbia 7:57 Xzibit Front 2 Back Loud Zeit Interpret Titel Label 8:05 Ludacris Roll Out DefJam 8:09 R. Kelly The World´s Greatest Jive 8:14 Exhale Chillin In Your Benz Real Deal 8:19 Mis-Teeq One Night Stand Telstar 8:22 Stephanie Mills This Empty Place Motown 8:26 Jennifer Lopez Feeln So Good Work 8:33 P. -

House Recommends Finals Schedule Review by Jaime Walker "When I Talked to Them

WEDNESDAY TODAY APRIL 12,2000 The TCU-UT 97th Year • Number 99 matchup at The Ballpark in High 67 Arlington was rained out Low 57 Tuesday night and will not Ww be rescheduled. TOMORROW High 73 Low 63 Sports, page 9 Fort Worth, Texas Serving Texas Christian University since 1902 www.skiff.tcu.edu House recommends finals schedule review By Jaime Walker "When I talked to them. 80 percent STAFF REPORTER SGA budgets for next year pass despite opposition, lack of debate voted against it." he said "I felt that's The House of Student Representa- what I had to do (Tuesday) because tives voted 23-20, with three absten- view the policy and come up with the made it very clear that they like the idea of a change," she said. "Person- grades are on the line. When we start they elected me to represent them." tions, to encourage the administration plan that is best for the students,'" said schedule the way it is." he said. "They ally, l take a lot of upper-level classes, considering changing the schedule Sherley Hall representative Jenny to review policies surrounding the fi- Brian Casebolt, chairman of the Aca- saw our proposal as just prolonging and I am already thinking of ways to during that time, it penetrates people, Specht also opposed the bill. For her. nals schedule. demic Affairs Committee. the inevitable. The way they look at use that day. It would make my life so and there are a lot of opinions." the vote was not just a chance to ex- In an individual role-call vote, each As he presented the resolution to it, finals are stressful anyway. -

B.Iiboa D R &B RADIO PLAYLISTS and RETAIL STORE SALES REPORTS 110T Roggini P Licip COLLECTED, COMPILED, and PROVIDED by SOUNDSCAN

COMPILED FROM A NATIONAL SAMPLE OF BROADCAST DATA SYSTEMS B.Iiboa d R &B RADIO PLAYLISTS AND RETAIL STORE SALES REPORTS 110T Roggini p_licip COLLECTED, COMPILED, AND PROVIDED BY SOUNDSCAN. O TM .I1n1 SoundScan® DECEMBER 25, 1999 1111111 IC .IniOM LElit AWILWEratiC KS ----D z z ¡,, OE- CJ rn zo ,- g W Ñ w o = TITLE ARTIST w w 3 o TITLE ARTIST IT. c.1 c5 PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) ó = i ó 3 a IMPRINT & NUMBER/PROMOTION LABEL a a IT 3 n 3 cv ¢ 3 5 PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT & NUMBER/PROMOTION LABEL a a QUIET STORM MOBB DEEP No. 1 50 43 45 37 * 35 `- HAVOC (A. JOHNSON ,K.MUCHITA,M.GLOVER,S.ROBINSON) (T) LOUD 65718 * /COLUMBIA t U KNOW WHAT'S UP 7 weeks at No. 1 DON JONES 1 1 1 1 18 EDDIEF., D. E. FERRELL, TY, UGHTY( D.UGH CUGHTY, D. MUHAMMAD ,AHAM)LTON,D,DAMONV.MCKENZIE) { CJ(O )UNTOUCHABLEM.VACE24420/ARISTAT I LIKE IT SAMMIE 51 54 - 2 * 51 D.AUSTIN (D.AUSTIN,G.WHITE) (C) (D) (T) FREEWORLD 58776/CAPITOL HOT BOYZ MISSY t 3 3 11 "MISDEMEANOR" ELLIOTT' FEAT. NAS, EVE & Q-TIP Q2 TIMBALAND 2 U UNDERSTAND (M.ELLIOTT,T.MOSLEY) (C) (D) (T) (X) THE GOLD MIND/EASTWEST 64029/EEG t 52 60 63 4 JUVENILE 52 M.FRESH (B.THOMAS,T.GREY) CASH MONEY ALBUM CJT 24/7 KEVON EDMONDS 3 2 2 16 * 2 A.RAY (A.RAY,SCOTT,SMITH) (C) (D) ) (X) RCA 65924 TURN YOUR LIGHTS DOWN LOW LAURYN HILL & BOB MARLEY (T) t 53 53 54 g 53 THE MARLEY BOYZ ( B .MARLEY,M.RIPERTON,R.J.RUDOLPH) COLUMBINISLAND /IDJMG ALBUM & SOUNDTRACK CUT t GREATEST GAINER/ALES/S `"`- DO IT AGAIN (PUT YA HANDS UP) JAY -Z FEAT. -

The Socio-Political Influence of Rap Music As Poetry in the Urban Community Albert D

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community Albert D. Farr Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Farr, Albert D., "The ocs io-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community" (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 182. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The socio-political influence of rap music as poetry in the urban community by Albert Devon Farr A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee Jane Davis, Major Professor Shirley Basfield Dunlap Jose Amaya Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 Copyright © Albert Devon Farr, 2002. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Albert Devon Farr has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Ill My Dedication This Master's thesis is dedicated to my wonderful family members who have supported and influenced me in various ways: To Martha "Mama Shug" Farr, from whom I learned to pray and place my faith in God, I dedicate this to you. -

Zj-W He Fasting

A SEL EC T I O N F R O M ’ M R . H EI N E M A N N S M ED I C A L A N D S C I E N T I F I C B O O ! S . T HE SIM PLE LIFE SER I ES. Ea chv l me r v th ri ce 2 . 6d . e . c . 8 o . c P 3 o u lo . n t WH Y WO R R Y ? B G R G I T MD EO E L N O LN WA O N . y C L . TH SE N ER V ES O . B GEO R GE LI N O LN W LTON MD . y C A . SEL F H EL P F O R N ER VO U S WO MEN . F ami l iar T al ks on Eco n o m in N erv ous Ex e i re. B O H N ! Ml C H ELL M D . p nd tu y J . I E TI I T ITI O IM I I ED SC N F C NU R N S PL F . A C ondensed S tatement and Ex l a n a tio n f or Ev e r bod of he O b erv i ? C h i e e y t s at ons o tt nd n . F l e tcfier ther . B GO OD WI N . and o s y BR OWN A M w i h S eme t r , t a uppl n a y C h er b .