That Championship Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Message

President’s Message his is perhaps the most exciting academic year ever on Hofstra’s campus, as we prepare to host the third and final presidential debate of the 2008 Telection season on October 15, and again present Educate ’08, our unprecedented series of lectures, conferences, exhibitions and events focused on the presidency, history, politics and social issues. For the fall Educate ’08 series, we host nationally known figures such as Robert Rubin and Paul O’Neill, George Stephanopoulos, Dee Dee Myers and Ari Fleischer, Mario Cuomo and the Council on Foreign Relations’ Richard Haass, and many other scholars, journalists and policymakers. The Center for Civic Engagement presents its sixth Day of Dialogue, with nearly 50 sessions on critical issues of the day for Democracy in Performance, a live performance featuring actors portraying historic figures. Many of our academic departments and centers, such as the Peter S. Kalikow Center for the Study of the American Presidency, the National Center for Suburban Studies, and Hofstra Entertainment, will also present events with a presidential theme. The Hofstra Cultural Center’s popular Joseph G. Astman International Concert Series features All American Music, while the Hofstra Cultural Center joins the Hofstra University Museum in presenting a reunion of the directors of Hofstra’s series of renowned presidential conferences for On the Record: A Hofstra Presidential Conference Retrospective. In addition to our exciting political series, the Hofstra Cultural Center and the academic departments continue to present a variety of lectures, concerts, dramatic performances and events that will engage and delight the entire Hofstra and surrounding communities. -

A Production of and Miss Reardon Drinks a Little

FISHER, ALBERT JAMES. A Production of And Miss Reardon Drinks a Little. (1975) Directed by: Miss Kathryn England. Pp. 107. It was the purpose of this study to research, produce and analyze the play And Miss Reardon Drinks a Little by Paul Zindel. The research of the play involved tracing previous productions of the play, the author's background, and study of the play itself. The production involved casting the play, assembling the crews and staging the play for performance on the mainstage of W. Raymond Taylor Theatre at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. The analysis involved evaluation of the finished performance in all areas of the production. A PRODUCTION OF AND MISS REARDON DRINKS A LITTLE by Albert James Fisher A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Greensboro 1975 Approved by APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Thesis Adviser Committee Members ^—-c*—AyuLtu r> Catatelof Acceptance by Committee ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is made to the faculty of the Theatre Division of the Department of Drama and Speech, especially Miss Kathryn England, thesis advisor, Dr. David R. Batcheller and Dr. Andreas Nomikos for their warmth and support and always generous help; to an excellent cast and crews; to Bonnie Becker, a superlative stage manager; to my friends Lauren K. Woods and Erminie Leonardis for their encouragement; to my parents; and to Jill Didier for her warm friendship during the difficult production period. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Author(s): DEREK H. ALDERMAN, JOSHUA INWOOD and JAMES A. TYNER Source: Southeastern Geographer , Vol. 58, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 227-249 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Southeastern Geographer This content downloaded from 152.33.50.165 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 18:12:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Race, Reputation, and the Politics of Black Villainy: The Fight of the Century DEREK H. ALDERMAN University of Tennessee JOSHUA INWOOD Pennsylvania State University JAMES A. TYNER Kent State University Foundational to Jim Crow era segregation and Fundacional a la segregación Jim Crow y a discrimination in the United States was a “ra- la discriminación en los EE.UU. -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller Revision Notes

Death of a Salesman By Arthur Miller Revision Notes Summary and Analysis of the play Act I - Opening scene to Willy’s first daydream Summary The play begins on a Monday evening at the Loman family home in Brooklyn. After some light changes on stage and ambient flute music (the first instance of a motif connected to Willy Loman’s faint memory of his father, who was once a flute-maker and salesman), Willy, a sixty-three-year-old travelling salesman, returns home early from a trip, apparently exhausted. His wife, Linda, gets out of bed to greet him. She asks if he had an automobile accident, since he once drove off a bridge into a river. Irritated, he replies that nothing happened. Willy explains that he kept falling into a trance while driving—he reveals later that he almost hit a boy. Linda urges him to ask his employer, Howard Wagner, for a non-travelling job in New York City. Willy’s two adult sons, Biff and Happy, are visiting. Before he left that morning, Willy criticized Biff for working at manual labour on farms and horse ranches in the West. The argument that ensued was left unresolved. Willy says that his thirty-four- year-old son is a lazy bum. Shortly thereafter, he declares that Biff is anything but lazy. Willy’s habit of contradicting himself becomes quickly apparent in his conversation with Linda. Willy’s loud rambling wakes his sons. They speculate that he had another accident. Linda returns to bed while Willy goes to the kitchen to get something to eat. -

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

African American Performance and Theater History: a Critical Reader

African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader Harry J. Elam, Jr. David Krasner, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS African American Performance and Theater History This page intentionally left blank ‘ ‘ African American Performance and Theater History a critical reader ‘‘‘ Edited by Harry J. Elam, Jr. David Krasner 1 2001 1 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota´ Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence HongKong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sa˜o Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright ᭧ 2001 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData African American performance and theater history: a critical reader / edited by Harry J. Elam, Jr. and David Krasner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–19–512724–2; ISBN 0–19–512725–0 (pbk.) 1. Afro-American theater. 2. American drama—Afro-American authors—History and criticism. I. Elam,Harry Justin. II. Krasner, David, 1952– PN2270.A35A46 2000 792'.089'96073—dc21 00–022463 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to making this book possible. We would like to begin by thanking our first editor, T. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

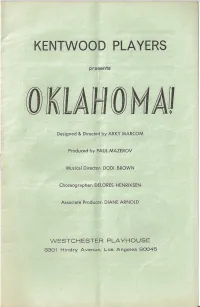

Program Design Paul Mazerov Program Coordinator

KENTWOOD PLAYERS presents Designed & Directed by ARKY MARCOM Produced by PAUL MAZEROV Musical Director: 0001, BROWN Choreographer: DELORESHENRIKSEN . Associate Producer: DIANE ARNOLD WESTCHESTER PLAYHOUSE 8301 Hindry Avenue, Los Angeles 90045 COMING ATTRACTIONS ... ~977 NOV. 11 to DEC. 17, "DIAL M FOR MURDER" - Exciting mystery by FREDERICK KNOTT. "Quiet in style but'tingling with excitement OKLAHOMA! underneath." - N.Y. Times. Director: Max Stormes. Casting: Sept. Music by: RICHARD RODGERS Book & Lyrics by: OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II 12·13,8:00 p.m. Producer: Chris David-Belyea. Based on LYNN RIGG'S "GREEN GROWS THE LILACS" As Originally Produced by: THE THEATRE GUILD. COMING ATTRACTIONS ... ~978 SPECIAL PERMISSION OF THE RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN MUSIC LIBRARY JAN. 20·FEB. 25, "BUTTERFLIES ARE FREE." By LEONARD GERSHE. "Funny when it means to be. sentimental when it is so CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE inclined, and heart warming." NN. Daily News. Director: C. Clarke Bell. f~B~~:~~;~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::~'i-~~~~1:~~:~5 MAR. 17·APRIL 22, "ALL THE WAY HOME." By TAD MOSEL. This IKE SKIDMORE . Norman Jay Goldman portrait of early 20th Century American life won both the Pulitzer ~~N\-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-_~~-_-_-_-_-_-_-_-=:':': -.-_-_-_.-:_-.'-_-_-:~~--D~-V~a~:_tl~:~s~1~-_~-_-_~~-_-_-_-_~-_-_-_-_-_-_- Prize and Critics' Circie Award. Director: Charles Briles. WILL PARKER Peter von Ehren ro~ JUD FRY __Lawrence Ma rrlll ADO ANNIE CARNES ' Jama Tege er SPECIAL GROUP RATES All HAKIM Peter M. Eberhardt GERTIE CUMMMINGS Molly Bea Tweten Kentwood Players offers your group or organization an attractive way to arrange a desirable social event, or to plan a fund-ralsing project for any worthy cause. -

The Heidi Chronicles As Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States

Facultad de Humanidades Sección de Filología The Heidi Chronicles as Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States Trabajo de Fin de Grado presentado por la alumna Beatriz Sánchez Ramos bajo la supervisión de la Dra. Matilde Martín González Dpto. Filología Inglesa y Alemana Grado en Estudios Ingleses Curso 2014-15 Convocatoria de julio de 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Second Feminist Wave: A Brief Account 3. The Heidi Chronicles seen from the perspective of Second Wave Feminist Theory 4. Conclusion 5. Works Cited Abstract This final degree dissertation aims to show how vital was the Second Wave Feminism in the twentieth century in terms of women’s struggle for better conditions. This period of intense fight has been the object of many literary and critical works, such as novels, collections of poetry and scholarly articles. From the huge bibliography on this topic I have chosen to focus on The Heidi Chronicles, a play written by Wendy Wasserstein (1950-2006) which reflects and engages with the main concerns raised by women in the period covering the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Thus, I argue that this text could very well illustrate the political, social and theoretical aspects developed within the Second Feminist Wave in the United States. A further reason for choosing this work has to do with the possibilities of theatre as a cultural manifestation to deal with questions that include gender relations and social themes. The theatre has always implied an interaction between characters in a literal way, and this turns it perhaps into the most straightforward genre to involve the public – the audience – or the readership. -

M. Butterfly As Total Theatre

M. Butterfly as Total Theatre Mª Isabel Seguro Gómez Universitat de Barcelona [email protected] Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly from the perspective of a semiotics on theatre, following the work of Elaine Aston and George Savona (1991). The reason for such an approach is that Hwang’s play has mostly been analysed as a critique of the interconnections between imperialism and sexism, neglecting its theatricality. My argument is that the theatrical techniques used by the playwright are also a fundamental aspect to be considered in the deconstruction of the Orient and the Other. In a 1988 interview, David Henry Hwang expressed what could be considered as his manifest on theatre whilst M. Butterfly was still being performed with great commercial success on Broadway:1 I am generally interested in ways to create total theatre, theatre which utilizes whatever the medium has to offer to create an effect—just to keep an audience interested—whether there’s dance or music or opera or comedy. All these things are very theatrical, even makeup changes and costumes—possibly because I grew up in a generation which isn’t that acquainted with theatre. For theatre to hold my interest, it needs to pull out all its stops and take advantage of everything it has— what it can do better than film and television. So it’s very important for me to exploit those elements.… (1989a: 152-53) From this perspective, I would like to analyse the theatricality of M. Butterfly as an aspect of the play to which, traditionally, not much attention has been paid to as to its content and plot.