Final Format.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

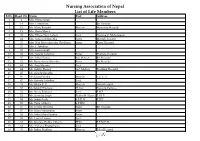

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Sweet Child of Mine

www.fridayweekly.com.np Every Thursday | ISSUE 64 | RS. 20 SUBSCRIBER COPY 27 April 2011 | !$ a}zfv @)^* �������� ������������������������������������������������� 4 5 10 157 16 17 PAGE3 PAGE3 HALLOFFRAME ENTERTAINMENT GOURMET GOURMET Summer Style Soul Connection About Town The Red Baron Crab in the Fields Delicious Memoirs Summer is here with a whole Excerpts from Mannat A photographic rewind This time, we pick Another remarkable Take home good food new season of style and Shrestha’s Rendezvous of the events and hap- the biopic on the invention from our memories and tangible fashion. Fashionistas from the with Kailash Kher – the penings in town – take a legendary WWI chef at play – a marine gifts and memoirs screen give us a sneak peek man who can make grown look at what you did or fighter pilot Manfred dish with a Nepali from your visit at Café into their summer wardrobe. men cry with his songs. didn’t miss. von Richthofen. twist! Cheeno. THE COMPLETE FAMILY MA GAZINE SWEET CHILD OF MINE KIDS PHOTO COMPETITION PRIZES WINNER n Bangkok Holiday Package for 4 (2 Adults + 2 Children – under 8 years) n Picture on the cover of Healthy Life’s July issue n Family photo frame from Photo Concern n Horlicks Gift Hamper worth Rs. 7,000 1st Runner Up n Children’s bedroom set from SB Furniture worth Rs. 67,000 n Horlicks gift hamper worth Rs. 3,000 2nd Runner Up n Microwave oven from IFB worth Rs. 24,000 n Horlicks gift hamper worth Rs.2,000 and many more prizes for more information visit healthylife.com.np PARTNERS www.fridayweekly.com.np Every Thursday | ISSUE 64 | RS. -

Nepal-Urban-Housing-Sector-Profile

NEPAL URBAN HOUSING SECTOR PROFILE Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2010 An electronic version of this publication is available for download from the UN-HABITAT web-site at http://www.unhabitat.org All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) P.O. Box 30030, GPO Nairobi 0010, Kenya Tel: +254 20 762 3120 Fax: +254 20 762 3477 Web: www.unhabitat.org DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the United Nations, and a failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. Excerpts from the text may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. HS Number: HS/079/11E ISBN Number (Volume): 978-92-1-132373-3 ISBN Number (Series): 978-92-1-131927-9 Layout: Gideon Mureithi Printing: UNON, Publishing Services Section, Nairobi, ISO 14001:2004-certified. NEPAL URBAN HOUSING SECTOR PROFILE NEPAL URBAN HOUSING SECTOR PROFILE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS HOUSING PROFILE CORE TEAM Supervisor: Claudio Acioly Jr. Task Managers: Christophe Lalande, Rasmus Precht and Lowie Rosales National Project Managers: Prafulla Man Singh Pradhan and Padma Sunder Joshi Principal Authors: Ester van Steekelenburg and the Centre for Integrated Urban Development Team (CIUD): Mr. -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

Peace Corps / Nepal 22

Peace Corps / Nepal 22 A Retrospective on the Post-Peace Corps Careers of Trainees, Trainers, Staff & RPCVs Peace Corps / Nepal 22 1970 - 2010 A Retrospective on the Post-Peace Corps Careers of Trainees, Trainers, Staff & RPCVs John P. Hughes, Editor Washington, DC March 2010 Dedicated to the Memory of Mike Furst (1927-2005) Peace Corps Country Director - Nepal 1970-72 Cover Photo: Tommy Randall and Jim Walsh resting at a pass south of Okhaldhunga in March 1972. 2 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Map of Nepal ....................................................................................................... 11 Nepal 22 Training Program ..................................................................................... 12 Rice Fields of the Nepal Terai ................................................................................... 27 Wheat Project in the Nepal Terai .............................................................................. 28 The Nixon Peace Corps .......................................................................................... 29 The Peace Corps & the Draft .................................................................................... 31 HMG & the Panchayat System .................................................................................. 33 Peace Corps Nepal Staff -

3 82 Page.Indd

July 2011 ISSUE 6, Rs. 30 facebook.com/teenzmagazine www.teenz.com.np YOUR TIME IS NOW ALL ABOUT THE HeartbreakHeartbreak BEAUTY QUEENS StoryStory 100 New4 gadgets what would you save if to watch out your house was on fi re Of Randolph And America A student shares her journey SlamSlam PoetsPoets inin thethe riserise DATING TRENDS From Around The World Colr Therapy- Heal yourself with clothes TeenageTeenage Crisis?Crisis? TACKLE THEM HEAD ON JULY | TEENZ ISSUE 6 JULY, 2011 JULY 2011 contents 49 TEENAGE CRISIS Red stripe shirt, United Colors of Benetton, Rs 4,799 Being a teenager is Levi’s Jeans, U.F.O, Rs 1,498 never easy with all Red stripe cotton belt, the problems you are United Colors of Benetton, Rs 1,500 bound to face, read Red tees, Store One, Rs 999 about everything you fear as a teenager. Yellow print tees, U.F.O, Rs 998 Purple half pant, Rs 398 47 ON THE COVER AND AS WE WALKED Read the exciting journey of our reporter as he follows the students of Gyanodaya Residential School on their hiking trip 47 COLOR THERAPY AHILYA SHARMA Learn how to splash PHOTOGRAPHY: new excitng color into PIX- THE LIGHT SKETCH your wardrobe. WARDROBE: FMIRROR.COM MAKE-UP & HAIR: LOKESH THAPA FASHION CO-ORDINATOR: NITESH SHERCHAN ISSUE 6 JULY, 2011 FEATURE CONFESSIONS CLIPPED WINGS Feel like a fl ightless bird? 58 Find out how different JULY BREAKING things can tie you down INTO 2011 BREAKUPS contents FEATURE 20 GAMING HIGH SCHOOL BLUES High-school can be a 18 grueling experience, read how diffi cult it could be RETRO RAVE Read how an out-dated console system has still inspired gamers FICTION 64 today. -

A 50Th Anniversary Report

Memories and Meaning: A 50th Anniversary Report Peace Corps Nepal Group 17 December 2018 i Foreword In his November 2, 1960 speech at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, then- Senator John F. Kennedy proposed "a peace corps of talented men and women" who would dedicate themselves to the progress and peace of developing countries. This report explores the experiences and impacts of the 17th such group to be sent to the fifth poorest country in the world: Nepal. The year was 1968, a time of political and social turmoil in the United States; it was a time for taking sides in the struggle for or against peace, justice, and equality. Each of the 32 lives reported here was transformed dramatically, unpredictably, and irreversibly with respect to those moral choices and guiding human values, impacting their career paths, life partners, and enduring personal relations, inside Nepal and out. Taken together, these writers attest to an amazing diversity of backgrounds at the time of entrance into the Peace Corps. They were intellectuals; farmers; foresters; recent graduates in economics, business, political science, linguistics, math, history, psychology and philosophy; and teachers of English and agricultural science. But thanks to intensive training in pre- mechanized agriculture, four South Asian languages and Hindu culture in both Cactus Corners, California and Parwanipur, Nepal, they were transformed into a dedicated team of volunteers ─ open, willing to learn, courageous, sincere, energetic, and peace-loving ─ in a word, fundamentally good people equipped as well as at all possible for the challenges ahead. Those challenges saw a total of 76 of us scattered far and wide into single postings across the taraai and middle hills of a 9-million-person country (see map, page 7). -

Voices from the Field: Country Partnership Strategy (2005-2009)

Voices from the Field: On the Road to Inclusion Between January and April 2008, the Nepal Resident Mission organized regional consultations as part of the country partnership strategy 2005–2009 midterm review. The consultations aimed to assess the ground realities and gather the local stakeholders' perceptions of the strategy's underlying assumptions, particularly in light of changes in Nepal's political situation since the strategy was formulated in 2004. This publication summarizes the responses, key discussions, and concerns and issues raised during the local consultations. About the Asian Development Bank VOICES ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its from the Field developing member countries substantially reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two Country Partnership Strategy (2005–2009) Midterm Review thirds of the world’s poor. Nearly 1.7 billion people in the region live on $2 or less a Regional Consultations day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. In 2007, it approved $10.1 billion of loans, $673 million of grant projects, and technical assistance amounting to $243 million. Head Office Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444 Fax +63 2 636 2444 [email protected] www.adb.org Nepal Resident Mission On the Srikunj, Kamaladi, Ward No.