Rhododendron Update 2 Ver4 290814

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Laurel Or Rhododendron? Recreation Area Vol

U.S. Dept. of the Interior National Park Service . Spanning the Gap The newsletter of Delaware Water Gap National Mountain Laurel or Rhododendron? Recreation Area Vol. 7 No. 2 Summer 1984 These two members of the plant kingdom are often confused. Especially before they blossom, they resemble each other with their bushy appearance and long, dark-green leaves. Both plants ARE shrubs, and they are often seen growing together. Another thing they have in common: although some species have not been proven dangerous, it is well to consider ALL members of the laurel- (Above) Rhodendron. rhododendron-azalea group of plants as potentially toxic. The rhododendron (rhododenron maximum) is undoubtedly the most conspicuous understory plant in the mountain forests of Pennsylvania. In ravines and hollows and along shaded watercourses it often grows so luxuriantly as to form almost impenetrable tangles. In June or early July, large clusters of showy blossoms, ranging from white to light rosy- pink, appear at the ends of the branchlets. People travel many miles to witness the magnificent show which is provided by the rhododendron at flowering time. In the southern Appalachians the plant grows much larger than it ordinarily does in this area, often becoming a tree 25 feet or more in height. The dense thickets of rhododendron in the stream valleys and on the lower slopes of our mountains are favorite yarding grounds for deer when the Rhodendron. snows become deep in the wintertime. The dark- green, leathery leaves react to subfreezing temperatures by bending downward and rolling into a tight coil. Although the shrub is often browsed to excess, it has little or no nutritional value. -

Rosebay Rhododendron Rhododendron Maximum

SUMMER 2004, VOLUME 5, ISSUE 3 NEWSLETTER OF THE NORTH AMERICAN NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY Native Plant to Know Rosebay rhododendron Rhododendron maximum by Kevin Kavanagh Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, tucked away inside the Nantahala National Forest RANTON of North Carolina’s Appalachian G Mountains, is one of those RIGITTE North American pil- B grimages that all botanists should make at least once in ILLUSTRATION BY their lives.As a graduate student in for- est ecology, I had read about it in the scientific literature, one of the best examples of an old-growth ‘cove’ forest on the continent: massive tulip trees (Lirio- dendron tulipifera) more than 500 years old, east- ern hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) rivalling their large elliptic leaves forming a delicate pat- Appalachian chain.Although hardy in eastern their west-coast tern against the bright yellows of overstorey Canadian gardens, Rhododendron maximum rainforest cousins tulip trees in peak autumn coloration.Along does not penetrate naturally into Canada. in size and age, mountain streams, the trails wove in among While there are historical accounts from and, along the expansive rhododendron thickets that in Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova streams, dense under- places rose more than 10 metres (30 feet) over- Scotia, none of them, to my knowledge, have storey stands of rosebay rhododendrons head on gnarled stems (trunks!), the largest of been authenticated. (Rhododendron maximum) forming a dark which were close to 30 centimetres (one foot) In its native range, rosebay rhododendron canopy overhead. in diameter. (also known as great-laurel or great rhododen- To call it a canopy is not embellishment. -

Rhododendron Glenn Dale Hybrid Azaleas

U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Rhododendron Glenn Dale Hybrid Azaleas Nothing says spring like azaleas! One of the National Arboretum’s most popular plantings, the Glenn Dale Azaleas draw thousands for annual spring viewing. Horticulturist Benjamin Y. Mor- rison worked for over 25 years to create this superior group of winter-hardy azaleas with large, colorful flowers suitable for the Washington, DC region. We present a small vignette of the 454 named introductions to entice you to grow these lovely spring treasures. Check our on-line photo gallery and be sure to make an April visit to the Arboretum part of your tradition too! The south face of Mt. Hamilton at the National Arboretum in Washington, DC was planted with approximately 15,000 azaleas from Glenn Dale in 1946-47. In 1949, the Arboretum opened to the public for the first time during the azalea bloom. U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave., N.E., Washington, DC 20002 Glenn Dale Hybrid Azaleas Botanical Name: Rhododendron Glenn Dale hybrids Plants in the Glenn Dale azalea breeding program were initially assigned Bell or "B" numbers an old name for the Plant Introduction Station at Glenn Dale, MD. Plant Introduction (PI) numbers were assigned later. The first “B” number was assigned to ‘Dimity’ in 1937. and ‘Satrap’ received the last “ B” number in 1951 and PI number in 1952. Family Ericaceae Hardiness: U.S.D.A. Zones 6b-8 (some hardy to Zone 5) Development: In the late 1920’s B.Y. -

Two New Species of Rhododendron (Ericaceae) from Guizhou, China

Two New Species of Rhododendron (Ericaceae) from Guizhou, China Xiang Chen South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 510650, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; and Institute of Biology, Guizhou Academy of Sciences, 550009, Guiyang, People’s Republic of China. [email protected] Jia-Yong Huang Research Division, Management Committee for Baili Rhododendron Scenic Spot of Guizhou, 551500, Qianxi, People’s Republic of China Laurie Consaul Research Division, Botany, Canadian Museum of Nature, P.O. Box 3443, Station D, Ottawa, Ontario K1P 6P4, Canada. [email protected] Xun Chen Guizhou Academy of Sciences, 550001, Guiyang, People’s Republic of China. Author for correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT . Two new species, Rhododendron huang- 2005; Fang et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2006) and pingense Xiang Chen & Jia Y. Huang and R. lilacinum hundreds of similar herbarium specimens, we de- Xiang Chen & X. Chen (Ericaceae), from Guizhou scribe two previously undescribed species here. Province, China, are described and illustrated. Rhododendron huangpingense is close to the morpho- 1. Rhododendron huangpingense Xiang Chen & logically similar species R. oreodoxa Franch. var. Jia Y. Huang, sp. nov. TYPE: China. Guizhou: adenostylosum Fang & W. K. Hu and the sympatric Baili Rhododendron Nature Reserve, Pudi, species R. decorum Franch., from which it differs by 27u149N, 105u519E, 1719 m, 22 Apr. 2008, having short yellowish brown hairs on the leaves, the Xiang Chen 08024 (holotype, HGAS; isotype, rachis 15–18 mm long, a rose-colored corolla with MO). Figure 1. deep rose flecks, and the stigma ca. -

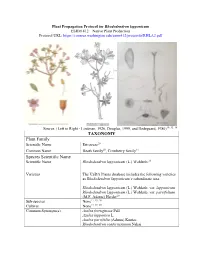

Plant Propagation Protocol for Rhododendron Lapponicum ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL

Plant Propagation Protocol for Rhododendron lapponicum ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/RHLA2.pdf Source: (Left to Right - Lindman, 1926, Douglas, 1999, and Hedegaard, 1980)10, 12, 16 TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Ericaceae20 Common Name Heath family20, Crowberry family14 Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb.20 Varieties The USDA Plants database includes the following varieties as Rhododendron lapponicum’s subordinate taxa. Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb. var. lapponicum Rhododendron lapponicum (L.) Wahlenb. var. parvifolium (M.F. Adams) Herder20 Sub-species None17, 19, 20 Cultivar None17, 19, 20 Common Synonym(s) Azalea ferruginosa Pall. Azalea lapponica L. Azalea parvifolia (Adams) Kuntze Rhododendron confertissimum Nakai Rhododendron lapponicum subsp. Parvifolium (Adams) T. Yamaz. Rhododendron palustre Turcz. Rhododendron parviflorum F. Schmidt Rhododendron parvifolium Adams Rhododendron parvifolium subsp. Confertissimum (Nakai) A.P. Khokhr.17, 19 Common Name(s) Lapland rosebay20 Species Code (as per USDA RHLA220 Plants database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range R. lapponicum’s circum-polar range includes North America’s Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, Europe’s Scandinavia and Russia, and Siberia and Northern Japan in Asia.1, 7, 11 Source: (USDA, 2018)20 Source: (Central Yukon Species Inventory Project, 2018)4 Ecological distribution R. lapponicum is found in the arctic tundra and is a circumpolar species that prefers limestone-rich clay, moss, and peat or igneous and serpentine soil types.5, 6, 8 Climate and elevation range R. lapponicum prefers cold arctic conditions and alpine elevations up to 6,000 feet.6, 8 Local habitat and abundance Because R. lapponicum is circum-polar, it is found in a variety of habitats and therefore does not have any commonly associated species.1, 6, 8, 11 Plant strategy type / successional R. -

Rhododendrons International the Online Journal of the World’S Rhododendron Organizations

Rhododendrons International The Online Journal of the World’s Rhododendron Organizations V i s re n y ro as d en od Rhod Azaleas Volume 2, 2018. Part 2 - Rhododendron Articles of Broad Interest Rhododendrons International 1 Contents ii From the Editor, GLEN JAMIESON 1 Part 1. Rhododendron Organisations in Countries with American Rhododendron Society Chapters 1 Canadian Rhododendron Societies, GLEN JAMIESON AND NICK YARMOSHUK 41 Danish Rhododendron Society, JENS HOLGER HANSEN 45 Rhododendron Society in Finland, KRISTIAN THEQVIST 57 Rhododendrons in the Sikkimese Himalayas, and the J.D. Hooker Chapter, KESHAB PRADHAN 73 Rhododendrons in The Netherlands and Belgium, HENRI SPEELMAN 86 Rhododendron Species Conservation Group, United Kingdom, JOHN M. HAMMOND 95 The Scottish Rhododendron Society, JOHN M. HAMMOND 102 Part 2. Rhododendron Articles of Broad Interest 102 Maintaining a National Collection of Vireya Rhododendrons, LOUISE GALLOWAY AND TONY CONLON 116 Notes from the International Rhododendron Register 2016, ALAN LESLIE 122 A Project to Develop an ex situ Conservation Plan for Rhododendron Species in New Zealand Collections, MARION MACKAY 128 A Summary of Twenty Years in the Field Searching for Wild Rhododendrons, STEVE HOOTMAN 138 Vireyas from West and East: Distribution and Conservation of Rhododendron section Schistanthe, MARION MACKAY JOURNAL CONTACTS Journal Editor: Glen Jamieson, Ph.D. Issue Layout: Sonja Nelson Journal Technical Reviewers: Gillian Brown, Steve Hootman, Hartwig Schepker, Barbara Stump. Comments on any aspect of this new journal and future articles for consideration should be submitted in digital form to: Dr. Glen Jamieson [email protected] Please put “Rhododendrons International” in the subject line. i From the Editor Dr. -

AZALEA (Rhododendron Sp. 'Mandarin Lights') J. W. Pscheidt, S

AZALEA (Rhododendron sp. ‘Mandarin Lights’) J. W. Pscheidt, S. Cluskey & J. P. Bassinette CAMELLIA (Camellia hybrid ‘April Dawn’) Dept. of Botany and Plant Pathology MAPLE (Acer palmatum ‘Bloodgood’) Oregon State University RHODODENRON (Rhododendron hybrid ‘Roseum Elegans’) Corvallis, OR 97331-2903 IR-4 Crop Safety Ornamental Protocol Numbers 10-015 and 10-024. Plants were obtained from local nurseries during the spring of 2010 and grown at the Botany and Plant Pathology Field Laboratory. Camellias (Camellia hybrid ‘April Dawn’) grown in 5 gal pots were received on 2 Apr. Plants arrived in good condition just past flowering and beginning to push new shoots. Deciduous azaleas (Rhododendron sp. ‘Mandarin Lights’) and evergreen rhododendrons (Rhododendron hybrid ‘Roseum Elegans’) grown in 1 gal pots were received on 13 Apr. Plants arrived in good condition and prior to bud break. Azaleas were cut back on 4 May to make working with the plants easier. Azaleas, Camellias and Rhododendrons were grown in a Quonset-style house covered only with shade cloth. Bare-root, dormant Japanese Maples (Acer palmatum ‘Bloodgood’) were received on 5 May. Trees (grade 3 ft CB) arrived bundled from cold storage ready to break bud and were healed into saw dust until potting. Trees were planted on 13 May into #10 sized pots with ‘Sun Grow Sunshine Mix SB40’ media (35 to 40% Canadian sphagnum peat moss, fir bark, pumice/cinders, dolomitic limestone, gypsum and a wetting agent). Trees were grown between widely spaced mature cherry trees. Fungicide treatments and plants (pots) for this trial were arranged in a randomized complete block design. -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

Microsoft Outlook

Joey Steil From: Leslie Jordan <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, September 25, 2018 1:13 PM To: Angela Ruberto Subject: Potential Environmental Beneficial Users of Surface Water in Your GSA Attachments: Paso Basin - County of San Luis Obispo Groundwater Sustainabilit_detail.xls; Field_Descriptions.xlsx; Freshwater_Species_Data_Sources.xls; FW_Paper_PLOSONE.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S1.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S2.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S3.pdf; FW_Paper_PLOSONE_S4.pdf CALIFORNIA WATER | GROUNDWATER To: GSAs We write to provide a starting point for addressing environmental beneficial users of surface water, as required under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). SGMA seeks to achieve sustainability, which is defined as the absence of several undesirable results, including “depletions of interconnected surface water that have significant and unreasonable adverse impacts on beneficial users of surface water” (Water Code §10721). The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a science-based, nonprofit organization with a mission to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. Like humans, plants and animals often rely on groundwater for survival, which is why TNC helped develop, and is now helping to implement, SGMA. Earlier this year, we launched the Groundwater Resource Hub, which is an online resource intended to help make it easier and cheaper to address environmental requirements under SGMA. As a first step in addressing when depletions might have an adverse impact, The Nature Conservancy recommends identifying the beneficial users of surface water, which include environmental users. This is a critical step, as it is impossible to define “significant and unreasonable adverse impacts” without knowing what is being impacted. To make this easy, we are providing this letter and the accompanying documents as the best available science on the freshwater species within the boundary of your groundwater sustainability agency (GSA). -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Washington Flora Checklist a Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium

Washington Flora Checklist A checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium The Washington Flora Checklist aims to be a complete list of the native and naturalized vascular plants of Washington State, with current classifications, nomenclature and synonymy. The checklist currently contains 3,929 terminal taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties). Taxa included in the checklist: * Native taxa whether extant, extirpated, or extinct. * Exotic taxa that are naturalized, escaped from cultivation, or persisting wild. * Waifs (e.g., ballast plants, escaped crop plants) and other scarcely collected exotics. * Interspecific hybrids that are frequent or self-maintaining. * Some unnamed taxa in the process of being described. Family classifications follow APG IV for angiosperms, PPG I (J. Syst. Evol. 54:563?603. 2016.) for pteridophytes, and Christenhusz et al. (Phytotaxa 19:55?70. 2011.) for gymnosperms, with a few exceptions. Nomenclature and synonymy at the rank of genus and below follows the 2nd Edition of the Flora of the Pacific Northwest except where superceded by new information. Accepted names are indicated with blue font; synonyms with black font. Native species and infraspecies are marked with boldface font. Please note: This is a working checklist, continuously updated. Use it at your discretion. Created from the Washington Flora Checklist Database on September 17th, 2018 at 9:47pm PST. Available online at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/waflora/checklist.php Comments and questions should be addressed to the checklist administrators: David Giblin ([email protected]) Peter Zika ([email protected]) Suggested citation: Weinmann, F., P.F. Zika, D.E. Giblin, B. -

Russian Gulch Vascular Plant List 2009 -Teresa Sholars

Russian Gulch Vascular Plant List 2009 -Teresa Sholars Rank Binomial Common Name Family FERNS Blechnaceae Struthiopteris spicant (Blechnum s.) deer fern Blechnaceae Dryopteridaceae Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum lady fern Dryopteridaceae Polystichum munitum western sword fern Dryopteridaceae Dennstaedtiaceae Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens bracken Dennstaedtiaceae Pteridaceae Adiantum aleuticum five-finger fern Pteridaceae GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae Hesperocyparis pygmaea (Cupressus p.) pygmy cypress Cupressaceae Pinaceae Abies grandis grand fir Pinaceae 1B.2 Pinus contorta ssp. bolanderi Bolander's pygmy pine Pinaceae Pinus contorta ssp. contorta beach pine Pinaceae Pinus muricata Bishop pine Pinaceae Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii Douglas fir Pinaceae Tsuga heterophylla western hemlock Pinaceae Taxodiaceae Sequoia sempervirens coast redwood Taxodiaceae EUDICOTS Anacardiaceae Toxicodendron diversilobum western poison oak Anacardiaceae Apiaceae Angelica hendersonii angelica Apiaceae Araceae Lysichiton americanus (Lysichiton americanum) yellow skunk cabbage Araceae Asteraceae Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae Adenocaulon bicolor trail plant Asteraceae Anaphalis margaritacea pearly everlasting Asteraceae Baccharis pilularis coyote brush Asteraceae Cirsium vulgare * bull thistle Asteraceae Gnaphalium sp. cudweed Asteraceae Senecio minimus (Erechtites minima) * Australian fireweed Asteraceae Carduus pycnocephalus Italian thistle Asteraceae Berberidaceae Achlys triphylla ssp. triphylla vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Berberis