Pdf Komiyama K, Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limnologica Effect of Eutrophication on Molluscan Community

Limnologica 41 (2011) 213–219 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Contents lists available at ScienceDirect provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Limnologica journal homepage: www.elsevier.de/limno Effect of eutrophication on molluscan community composition in the Lake Dianchi (China, Yunnan) Du Li-Na 1, Li Yuan 1, Chen Xiao-Yong ∗, Yang Jun-Xing ∗ State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650223, China article info abstract Article history: In this paper, three historical biodiversity datasets (from 1940s, 1980–1999 and 2000–2004) and results Received 9 September 2009 from the recent inventory are used to trace the long-term changes of the mollusks in the eutrophic Lake Received in revised form 28 July 2010 Dianchi. Comparison of the obtained results with those of earlier investigations performed during the Accepted 24 September 2010 period of 1940s and 1980–1999 as well as 2000–2004 showed that changes have occurred in the interval. There were 31 species and 2 sub-species recorded prior to the 1940s, but the species richness decreased Keywords: from a high level of 83 species and 7 sub-species to 16 species and one sub-species from 1990s to the Eutrophication early of 21st century in lake body. Species from the genera of Kunmingia, Fenouilia, Paraprygula, Erhaia, Mollusks community Dianchi basin Assiminea, Galba, Rhombuniopsis, Unionea and Aforpareysia were not found in Dianchi basin after 2000. The Historical datasets species from the genera Lithoglyphopsis, Tricula, Bithynia, Semisulcospira and Corbicula were only found in the springs and upstream rivers. -

Research and Practice in the Schools

Research and Practice in the Schools The Official Journal of the Texas Association of School Psychologists Volume 7, Issue 1 February 2020 Special Issue on Trauma-Informed School Psychology Practices Guest Editors: Julia Englund Strait, Kirby Wycoff, and Aaron Gubi Research and Practice in the Schools: The Official Journal of the Texas Association of School Psychologists Volume 7, Issue 1 February 2020 Special Issue on Trauma-Informed School Psychology Practices Guest Editors: Julia Englund Strait, Kirby Wycoff, and Aaron Gubi Editors: Jeremy R. Sullivan, University of Texas at San Antonio Arthur E. Hernandez, University of the Incarnate Word Editorial Review Board: Stephanie Barbre, HONDA Shared Service Arrangement A. Alexander Beaujean, Baylor University Felicia Castro-Villarreal, University of Texas at San Antonio Christy Chapman, Texas Tech University Sarah Conoyer, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Krystal (Cook) Simmons, Texas A&M University Kathy DeOrnellas, Texas Woman’s University Norma Guerra, University of Texas at San Antonio Elise N. Hendricker, University of Houston – Victoria David Kahn, Galena Park ISD Samuel Y. Kim, Texas Woman’s University Laurie Klose, RespectED, LLC Jennifer Langley, Grace Psychological Services, PLLC Coady Lapierre, Texas A&M University – Central Texas Ron Livingston, University of Texas at Tyler William G. Masten, Texas A&M University – Commerce Daniel McCleary, Stephen F. Austin State University Anita McCormick, Texas A&M University Ryan J. McGill, College of William & Mary Kerri Nowell, -

Aes Corporation

THE AES CORPORATION THE AES CORPORATION The global power company A Passion to Serve A Passion A PASSION to SERVE 2000 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT THE AES CORPORATION 1001 North 19th Street 2000 Arlington, Virginia 22209 USA (703) 522-1315 CONTENTS OFFICES 1 AES at a Glance AES CORPORATION AES HORIZONS THINK AES (CORPORATE OFFICE) Richmond, United Kingdom Arlington, Virginia 2 Note from the Chairman 1001 North 19th Street AES OASIS AES TRANSPOWER Arlington, Virginia 22209 Suite 802, 8th Floor #16-05 Six Battery Road 5 Our Annual Letter USA City Tower 2 049909 Singapore Phone: (703) 522-1315 Sheikh Zayed Road Phone: 65-533-0515 17 AES Worldwide Overview Fax: (703) 528-4510 P.O. Box 62843 Fax: 65-535-7287 AES AMERICAS Dubai, United Arab Emirates 33 AES People Arlington, Virginia Phone: 97-14-332-9699 REGISTRAR AND Fax: 97-14-332-6787 TRANSFER AGENT: 83 2000 AES Financial Review AES ANDES FIRST CHICAGO TRUST AES ORIENT Avenida del Libertador COMPANY OF NEW YORK, 26/F. Entertainment Building 602 13th Floor A DIVISION OF EQUISERVE 30 Queen’s Road Central 1001 Capital Federal P.O. Box 2500 Hong Kong Buenos Aires, Argentina Jersey City, New Jersey 07303 Phone: 852-2842-5111 Phone: 54-11-4816-1502 USA Fax: 852-2530-1673 Fax: 54-11-4816-6605 Shareholder Relations AES AURORA AES PACIFIC Phone: (800) 519-3111 100 Pine Street Arlington, Virginia STOCK LISTING: Suite 3300 NYSE Symbol: AES AES ENTERPRISE San Francisco, California 94111 Investor Relations Contact: Arlington, Virginia USA $217 $31 Kenneth R. Woodcock 93% 92% AES ELECTRIC Phone: (415) 395-7899 $1.46* 91% Senior Vice President 89% Burleigh House Fax: (415) 395-7891 88% 1001 North 19th Street $.96* 18 Parkshot $.84* AES SÃO PAULO Arlington, Virginia 22209 Richmond TW9 2RG $21 Av. -

1 Pronocephaloid Cercariae

This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Journal of Helminthology. The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X19000981. Pronocephaloid cercariae (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda) from gastropods of the Queensland coast, Australia. Thomas H. Cribb1, Phoebe A. Chapman2, Scott C. Cutmore1 and Daniel C. Huston3 1 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia. 2 Veterinary-Marine Animal Research, Teaching and Investigation, School of Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland, Gatton, QLD 4343, Australia. 3Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, The University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia. Running head: Queensland pronocephaloid cercariae. Author for correspondence: D.C. Huston, Email: [email protected]. 1 Abstract The superfamily Pronocephaloidea Looss, 1899 comprises digeneans occurring in the gut and respiratory organs of fishes, turtles, marine iguanas, birds and mammals. Although many life cycles are known for species of the Notocotylidae Lühe, 1909 maturing in birds and mammals, relatively few are known for the remaining pronocephaloid lineages. We report the cercariae of five pronocephaloid species from marine gastropods of the Queensland coast, Australia. From Lizard Island, northern Great Barrier Reef, we report three cercariae, two from Rhinoclavis vertagus (Cerithiidae) and one from Nassarius coronatus (Nassariidae). From Moreton Bay, southern Queensland, an additional two cercariae are reported from two genotypes of the gastropod worm shell Thylacodes sp. (Vermetidae). Phylogenetic analysis using 28S rRNA gene sequences shows all five species are nested within the Pronocephaloidea, but not matching or particularly close to any previously sequenced taxon. In combination, phylogenetic and ecological evidence suggests that most of these species will prove to be pronocephalids parasitic in marine turtles. -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A. -

![Transatlantica, 1 | 2011, « Senses of the South / Référendums Populaires » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 20 Décembre 2011, Consulté Le 29 Avril 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8299/transatlantica-1-2011-%C2%AB-senses-of-the-south-r%C3%A9f%C3%A9rendums-populaires-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-20-d%C3%A9cembre-2011-consult%C3%A9-le-29-avril-2021-2808299.webp)

Transatlantica, 1 | 2011, « Senses of the South / Référendums Populaires » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 20 Décembre 2011, Consulté Le 29 Avril 2021

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2011 Senses of the South / Référendums populaires Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5221 DOI : 10.4000/transatlantica.5221 ISSN : 1765-2766 Éditeur AFEA Référence électronique Transatlantica, 1 | 2011, « Senses of the South / Référendums populaires » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 20 décembre 2011, consulté le 29 avril 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5221 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.5221 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 29 avril 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Senses of the South Dossier dirigé par Géraldine Chouard et Jacques Pothier Senses of the South Géraldine Chouard et Jacques Pothier The Gastrodynamics of Edna Pontellier’s liberation. Urszula Niewiadomska-Flis “Key to the highway”: blues records and the great migration Louis Mazzari Eudora Welty: Sensing the Particular, Revealing the Universal in Her Southern World Pearl McHaney Tennessee Williams’s post-pastoral Southern gardens in text and on the movie screen Taïna Tuhkunen “Magic Portraits Drawn by the Sun”: New Orleans, Yellow Fever, and the sense(s) of death in Josh Russell’s Yellow Jack Owen Robinson Imagining Jefferson and Hemings in Paris Suzanne W. Jones Référendums populaires Dossier dirigé par Donna Kesselman Direct Democracy -

A Morphological, Molecular and Life Cycle Study of the Capybara Parasite Hippocrepis Hippocrepis (Trematoda: Notocotylidae)

RESEARCH ARTICLE A morphological, molecular and life cycle study of the capybara parasite Hippocrepis hippocrepis (Trematoda: Notocotylidae) Jordana C. A. Assis☯, Danimar Lopez-HernaÂndez³, Eduardo A. Pulido-Murillo³, Alan ³ ☯ L. Melo , Hudson A. PintoID * LaboratoÂrio de Biologia de Trematoda, Department of Parasitology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Hippocrepis hippocrepis is a notocotylid that has been widely reported in capybaras; how- ever, the molluscs that act as intermediate hosts of this parasite remain unknown. Further- OPEN ACCESS more, there are currently no molecular data available for H. hippocrepis regarding its Citation: Assis JCA, Lopez-HernaÂndez D, Pulido- Murillo EA, Melo AL, Pinto HA (2019) A phylogenetic relationship with other members of the family Notocotylidae. In the present morphological, molecular and life cycle study of study, we collected monostome cercariae and adult parasites from the planorbid Biompha- the capybara parasite Hippocrepis hippocrepis laria straminea and in the large intestine of capybaras, respectively, from Belo Horizonte, (Trematoda: Notocotylidae). PLoS ONE 14(8): Minas Gerais, Brazil. We subjected them to morphological and molecular (amplification and e0221662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0221662 sequencing of partial regions of 28S and cox-1 genes) studies. Adult parasites collected from the capybaras were identified as H. hippocrepis and the sequences obtained for both Editor: Petr Heneberg, Charles University, CZECH REPUBLIC molecular markers showed 100% similarity with monostome cercariae found in B. -

Tuesday, November 19, 2013 13

Tuesday, November 19, 2013 13 08:00-09:00 Your own personal genome: ethical issues in direct- Welcome coffee to-consumer (DTC) genomics services Amy Michelle DeBaets, USA 09:00-10:30 The ethics of preimplantational diagnosis in “savior” CONSULTA WORKSHOP (1) Hall B embryos ETHICS AND MEDICINE: ISSUES AND PROBLEMS IN Iuri Cosme Dutra da Silva, Brazil SOME AWARD AREAS – I Co-Chairs: Antonio Lepre, Filiberto Cimino Enhancing human persons: does it violate human “Nature”? Current legislation in the field of preimplantation Jason T. Eberl, USA genetic diagnosis in European Union members Francesco Paolo Busardò, Italy Genetic data protection and reuse: ethical implications and legal issues Which consent in biobank-based research María Magnolia Pardo-López, Spain Gianluca Montanari Vergallo, Italy WPA SECTION ON PSYCHIATRY, Hall E The donation of a person’s body after death: a question LAW AND ETHICS (1) of ethics and science Co-Chairs: Oren Asman, Harold J. Bursztajn Alessandro Bonsignore, Italy Ethical considerations in legal representation of older Clinical experimentation on vulnerable subjects: issues clients with diminished capacity or impaired on the evaluation of a study on patients of the Italian competence secure hospitals (OPG) Meytal Segal-Reich, Israel Valeria Marino, Italy The study of massive psychic trauma and resilience is Immigrants! How Italian emergency health workers fundamental for ethically informed psychiatric perceive the “other” patients diagnosis, treatment and forensic evaluation Paola Antonella Fiore, Italy Harold -

Escinsighteurovision2011guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Foreword 3 Editors Introduction 4 Albania 5 Armenia 7 Austria 9 Azerbaijan 11 Belarus 13 Belgium 15 Bosnia & Herzegovina 17 Bulgaria 19 Croatia 21 Cyprus 23 Denmark 25 Estonia 27 FYR Macedonia 29 Finland 31 France 33 Georgia 35 Germany 37 Greece 39 Hungary 41 Iceland 43 Ireland 45 Israel 47 Italy 49 Latvia 51 Lithuania 53 Malta 55 Moldova 57 Norway 59 Poland 61 Portugal 63 Romania 65 Russia 67 San Marino 69 Serbia 71 Slovakia 73 Slovenia 75 Spain 77 Sweden 79 Switzerland 81 The Netherlands 83 Turkey 85 Ukraine 87 United Kingdom 89 ESC Insight – 2011 Eurovision Info Book Page 2 of 90 Foreword Willkommen nach Düsseldorf! Fifty-four years after Germany played host to the second ever Eurovision Song Contest, the musical jamboree comes to Düsseldorf this May. It’s a very different world since ARD staged the show in 1957 with just 10 nations in a small TV studio in Frankfurt. This year, a record 43 countries will take part in the three shows, with a potential audience of 35,000 live in the Esprit Arena. All 10 nations from 1957 will be on show in Germany, but only two of their languages survive. The creaky phone lines that provided the results from the 100 judges have been superseded by state of the art, pan-continental technology that involves all the 125 million viewers watching at home. It’s a very different show indeed. Back in 1957, Lys Assia attempted to defend her Eurovision crown and this year Germany’s Lena will become the third artist taking a crack at the same challenge. -

205 Book Reviews Samer S. Yohanna, the Gospel of Mark in the Syriac Harklean Version. an Edition Based Upon the Earliest Witness

Book Reviews Samer S. Yohanna, The Gospel of Mark in the Syriac Harklean Version. An Edition Based upon the Earliest Witnesses, Biblica et Orientalia 52 (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2015). Pp. xi + 196; € 60. ANDREAS JUCKEL,UNIVERSITY OF MÜNSTER The book under review is the doctoral dissertation of Samer Soreshow Yohanna, Chaldean priest and member of the Chal- dean Antonian Order of St. Hormizd (Iraq). It was supervised by Craig Morrison, O. Carm. and St. Pisano, S. J. and defended in 2014 at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome. The idea behind this book is clear and simple: to provide scholars with the (still missing) critical edition of the arklean Gospel of Mark, based on the earliest arklean manuscripts and pre- sented ‘in a user-friendly style, that will allow scholars to read this version, study its character and appreciate its place in the New Testament criticism’ (p. 8). The introduction clearly states that this book does not intend to offer such a text-critical study, but rather a convenient display of the Syriac evidence as a preparatory stage for textual criticism and for establishing the ‘original’. There is no explicit theory concerning the history of the text or the ‘critical’ approach to the ‘original’. A critical im- pact Yohanna expects from the restriction to the earliest arklean Gospel manuscripts and especially from the inclusion of his ms. C, a Gospel codex in the possession of the Chalde- ans in Iraq, which here for the first time is fully described and used in a scholarly publication.1 This 10th/11th cent. -

The Great Patriotic

MAY 2009 www.passportmagazine.ru The Great Patriotic War In Films and TV Fred Flintstone Pays the Bills Mamo Mia! The alternative universe of the Eurovision Song Contest Travel to: The Kamchatka Peninsular, Mongolia, the Russian North Robert De Niro at Nobu Contents 4 What’s On in Moscow 7 May Holidays 8 Previews Passport selection of May cultural events 8 15 Sport Expat Over 28s Football League 16 Ballet Napoli at the Stansilavsky and Nemirovich- Danchenko Music Theater 20 Cinema Russian War Films 16 The Animation Industry in Trouble 24 Art History Bari-Aizenman Anatoly Bichukov 28 City Beat Izmailovsky Park The History of Kiosks 28 32 Religion St. Catherine’s Church, Moscow 34 Travel Kamchatka Mongolia Kargopolye (The Russian North) 34 42 Restaurant Review Nobu. Opening in Moscow 44 Wine Tasting Four Years of Bordeaux Wines 46 Wine & Dine Listings 48 Out & About 48 50 How To Get a bicycle or scooter in Moscow 52 Columns Legal Column. Daniel Klein Financial Column. Matthew Partridge Real estate Column. Michael Bartley Flintstone tells Wilma where the money has gone 50 May 2009 1 Letter from the Publisher The inclusion of an article about Soviet war fi lms in this month’s Passport is a refl ection of the importance that the Great Patriotic War Expats Are Welcome still plays in Russians’ consciousness. There has been a resurgence in The New English Communication Club interest in war fi lms and TV serials about the Great Patriotic War and viewing ratings have soared. This is hardly surprising given the sheer (NECC) meets twice a week at Cofemax cafe. -

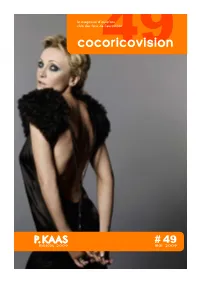

Cocoricovision49

le magazine d’eurofans club des fans de l’eurovision cocoricovision49 P. KAAS 49 moscou 2009 mai# 2009 édito C’est quand même surprenant qu’il ne saisisse pas cette occasion ! C’est vrai, normalement, en temps de crise, rien ne vaut un grand événement (sportif le plus souvent mais là on en est pas loin) pour faire oublier aux masses leur quotidien, leur belle-mère et leur banquière. En plus c’est chez son copain Poutine ! (Décidément il a plein d’amis français…) Moi j’imagine déjà partout dans Paris des calicots à l’effigie de P.K. surplombée d’un oiseau de paradis. Une petite allocution télé pour l’occasion ce serait bien aussi. Bien sûr si l’avion de la délégation norvégienne n’explose pas en vol, que la Turque se met à marcher SOMMAIRE en pataugasses (oui ça évite les entorses le billet du Président. 02 intempestives) et que la machine 54ème concours eurovision de la chanson infernale ukrainienne demi-finale 1 - 12 mai 2009 . 05 reste bloquée dans les cintres, demi-finale 2 - 14 mai 2009 . 23 ça fait beaucoup finale - 16 mai 2009 . 42 d’investissements, pour qu’au bout du compte, infos en vrac . 47 M’dame Michu n’oublie previews 2009 . 48 rien du tout. Mais moi je dis, dans la vie, faut le choix des eurofans . 52 être joueur. Allé Nico, le pronostic des eurofans . 53 faut y croire ! Paris 2010 ! 10 années qui ont changé... 54 bonne chance Patricia ! . 59 … en attendant, voici le cocoricovision n°49. Copycat fait rêver la Belgique ! .