A Flora of Waterton Lakes National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Floristic Inventory of Subalpine Parks in the Coeur D'alene River Drainage, Northern Idaho

FLORISTIC INVENTORY OF SUBALPINE PARKS IN THE COEUR D'ALENE RIVER DRAINAGE, NORTHERN IDAHO by Robert K. Moseley Conservation Data Center December 1993 Idaho Department of Fish and Game Natural Resource Policy Bureau 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost-share Project Idaho Panhandle National Forests Idaho Department of Fish and Game ABSTRACT Treeless summits and ridges in the otherwise densely forested mountains of northern Idaho, have a relatively unique flora compared with surrounding communities. Although small in area, these subalpine parks add greatly to the biotic diversity of the regional landscape and are habitats for several vascular taxa considered rare in Idaho. I conducted a floristic inventory of 32 parks in the mountains of the Coeur d'Alene River drainage and adjacent portions of the St. Joe drainage. The project is a cooperative one between the Idaho Department of Fish and Game's Conservation Data Center and the Idaho Panhandle National Forest. The subalpine park flora contains 151 taxa representing 97 genera in 34 families. Carex are surprisingly depauperate, in terms of both numbers and cover, as is the alien flora, which is comprised of only three species. I discovered populations of five rare species, including Carex xerantica, which is here reported for Idaho for the first time. Other rare species include Astragalus bourgovii, Carex californica, Ivesia tweedyi, and Romanzoffia sitchensis. Stevens Peak is the highest summit and is phytogeographically unique in the study area. It contains habitat for six taxa occurring nowhere else in the study area, all having high-elevation cordilleran or circumboreal affinities. -

Plant List As of 3/19/2008 Tanya Harvey T23S.R1E.S14 *Non-Native

compiled by Bohemia Mountain & Fairview Peak Plant List as of 3/19/2008 Tanya Harvey T23S.R1E.S14 *Non-native FERNS & ALLIES Cupressaceae Caprifoliaceae Blechnaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Lonicera ciliosa Alaska yellowcedar orange honeysuckle Blechnum spicant deer fern Calocedrus decurrens Lonicera conjugialis incense cedar purple-flowered honeysuckle Dennstaediaceae Juniperus communis Lonicera utahensis Pteridium aquilinum common juniper Utah honeysuckle bracken fern Sambucus mexicana Dryopteridaceae Pinaceae Abies amabilis blue elderberry Athyrium alpestre Pacific silver fir alpine lady fern Sambucus racemosa Abies concolor x grandis red elderberry Athyrium filix-femina hybrid white/grand fir lady fern Symphoricarpos albus Abies grandis common snowberry Cystopteris fragilis grand fir fragile fern Symphoricarpos mollis Pinus contorta var. latifolia creeping snowberry Dryopteris expansa lodgepole pine mountain shield-fern Celastraceae Pinus monticola Paxistima myrsinites Polystichum imbricans western white pine Oregon boxwood imbricate sword fern Pseudotsuga menziesii Polystichum lonchitis Cornaceae Douglas-fir holly fern Cornus nuttallii Tsuga heterophylla Pacific dogwood Polystichum munitum western hemlock sword fern Ericaceae Tsuga mertensiana Equisetaceae Arbutus menziesii mountain hemlock madrone Equisetum telmateia giant horsetail Taxaceae Arctostaphylos nevadensis Taxus brevifolia pinemat manzanita Polypodiaceae Pacific yew Gaultheria ovatifolia Polypodium glycyrrhiza slender wintergreen licorice fern TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS -

Botanical Resources Studies Final Report

Takatz Lake Hydroelectric Project Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Project No. 13234 Botanical Resources Studies Final Report Prepared for: City and Borough of Sitka Electric Department 105 Jarvis Street Sitka, Alaska 99835 Prepared by: HDR Alaska, Inc. 2525 C Street, Suite 305 Anchorage, AK 99503 In association with Lazy Mountain Biological Consulting Inundated club moss (Lycopodiella inundata) January 2014 Takatz Lake Hydroelectric Project, FERC No. 13234 Botanical Resources Studies - Final Report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction and Scope of the Studies .............................................................................................. 1 2 Study Area .......................................................................................................................................... 1 3 Literature and Information Review ................................................................................................. 5 3.1 Vegetation Types ....................................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Sensitive and Rare Plant Species ............................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Threatened and Endangered Species ............................................................................ 6 3.2.2 USFS-Designated Sensitive Species ........................................................................... -

An Illustrated Key to the Hydrophyllaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE HYDROPHYLLACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and written by Lorna Allen & Linda Kershaw September 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using information primarily from Moss (1983), Douglas et. al. (1999), and Lesica (2012). Taxonomy follows VASCAN (Brouillet, 2019). The main references are listed at the end of the key. Please let us know if there are ways in which the keys can be improved. The 2018 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SH; SU, according to ACIMS, 2018) are noted in superscript (S1;S2;SU) after the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotic species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). HYDROPHYLLACEAE Waterleaf Family Key to Genera 01a Leaves mostly basal, kidney-shaped to rounded, shallowly lobed to deeply toothed (resembling some Micranthes species); plants ± hairless . Romanzoffia sitchensis S2 01b Stem and basal leaves present (or only stem leaves), mostly egg- to lance-shaped in outline (egg-shaped to round in Phacelia campanularia), smooth-edged to coarsely toothed or pinnately lobed; plants variously hairy . 02 1a 02a Flowers mostly solitary in leaf axils; uncommon, → in swAB . 03 02b Flowers in few- to many-flowered clusters (cymes) in leaf axils and/or at stem tips; variously distributed . 04 3a 03a Leaf lobes 3-5, smooth-edged; 2 persistent cotyledon leaves at the stem base, green, elliptic to spoon-shaped; flower stalks nodding; 3b calyx with tiny (<1 mm long) appendages bent- back between the sepals (→); stems with tiny, 4a downward-pointing prickles . -

Download a Printable Hiking Guide

Waterton Lakes National Park (continued) Lewis & Clark National Forest (continued) Genuine Montana Crandell Lake Trail: 2.18 Miles — Moderate Muddy Creek Falls: 5.0 Miles — Moderate This trail is short, scenic, and easy for the entire family. The trail This walk kicks off from the Old North Trail country and travels a rambles gently in either direction, revealing stunning views of mile down an old gas development road. The next mile will be off Mount Dungarvan, Blackiston Creek, Mount Crandell, and its -trail, with some rock hopping up the stream bed, through a Utah namesake, Crandell Lake. Resting pristinely in a low forested sad- -like canyon to the pristine falls. You will view a formerly pro- dle between Mount Crandell and Ruby Ridge, Crandell Lake is a posed well site deep in the canyon and wander through the larg- gorgeous emerald green color and often still as glass. Pristinely lush est old growth Douglas fir forest this side of the Divide. in the summer, Crandell Lake Trail is also popular for snowshoeing Paine Gulch: 6 Miles — Moderate when winter comes around. This hike walks up a valley to an open burn from the big Monarch Lineham Falls: 5.2 Miles — Moderate Burn that occurred over Labor Day in 2001. You will see lots of Great Falls is centrally located where the A hike to Lineham Falls is an easy day hike that leads through for- wild flowers that have been covered by snow all winter, as well as mountains meet the high plains. It is the gateway to ests of lodge-pole pine and aspen trees, switchbacks gently a mix of deciduous and evergreen trees. -

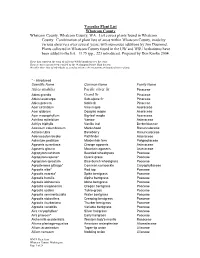

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA. List covers plants found in Whatcom County. Combination of plant lists of areas within Whatcom County, made by various observers over several years, with numerous additions by Jim Duemmel. Plants collected in Whatcom County found in the UW and WSU herbariums have been added to the list. 1175 spp., 223 introduced. Prepared by Don Knoke 2004. These lists represent the work of different WNPS members over the years. Their accuracy has not been verified by the Washington Native Plant Society. We offer these lists to individuals as a tool to enhance the enjoyment and study of native plants. * - Introduced Scientific Name Common Name Family Name Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir Pinaceae Abies grandis Grand fir Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Sub-alpine fir Pinaceae Abies procera Noble fir Pinaceae Acer circinatum Vine maple Aceraceae Acer glabrum Douglas maple Aceraceae Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf maple Aceraceae Achillea millefolium Yarrow Asteraceae Achlys triphylla Vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Aconitum columbianum Monkshood Ranunculaceae Actaea rubra Baneberry Ranunculaceae Adenocaulon bicolor Pathfinder Asteraceae Adiantum pedatum Maidenhair fern Polypodiaceae Agoseris aurantiaca Orange agoseris Asteraceae Agoseris glauca Mountain agoseris Asteraceae Agropyron caninum Bearded wheatgrass Poaceae Agropyron repens* Quack grass Poaceae Agropyron spicatum Blue-bunch wheatgrass Poaceae Agrostemma githago* Common corncockle Caryophyllaceae Agrostis alba* Red top Poaceae Agrostis exarata* -

Aterton - Glacier

ATERTON - GLACIER f _r«« Free Summer Newspaper Serving the Waterton - Glacier International Peace Park Region j_^RfONPARJT July 21,1999 Vol 8, Issue 7 Glacier's plan to preserve a "classic western national sr: park" by Reta Gilbert WEST GLACIER - After nearly four years of work, Glacier National Park last week released the almost-final version of their Gen p eral Management Plan - a guide to managing MCHERa.ElW GNP for the next 20 years. First the plan is published in the U.S. Feder al Register. After a 30 day public notification GJti&. period, the plan will be sent to John E. Cook, National Park Service Intermountain Region director, for his signature. When he signs, at last, the plan is final. The final version of the General Manage ment Plan is more a guide on how to proceed rather than a detailed plan of action. The goal remains to preserve Glacier as a "classic western national park". The top priority is the reconstruction of Going-to-the-Sun road. Instead of the old alter native where the road would be repaired on a fast track schedule with the west side to Logan Pass closed for up to two years and the east side up to Logan Pass closed for another two ,___?« MACLEOD' years, now the Park suggests a procedure to develop a plan but no plan is proposed. Busi ness response to the closures proposed last year GV>» was swift, immediate, and negative. No one liked closing the road. However, the steadily SWinCJSlGrS. Taking advantage of some ofthe little sunshine the region has deteriorating condition of Sun road does not had since spring are Cas, Monet and Mauve Holt, of Cardston. -

An Inventory of Rare Plants of Misty Fiords National Monument, Usda Forest Service, Region Ten

AN INVENTORY OF RARE PLANTS OF MISTY FIORDS NATIONAL MONUMENT, USDA FOREST SERVICE, REGION TEN A Report by John DeLapp Alaska Natural Heritage Program ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE University of Alaska Anchorage 707 A Street, Anchorage, Alaska 99501 February 8, 1994 ALASKA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 707 A Street • Anchorage, Alaska 99501 • (907) 279-4523 • Fax (907) 276-6847 Dr. Douglas A. Segar, Director Dr. David C. Duffy, Program Manager (UAA IS AN EO/AA EMPLOYER AND EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This cooperative project was the result of many hours of work by people within the Misty Fiords National Monument and the Ketchikan Area of the U.S. Forest Service who were dedicated to our common objectives and we are grateful to them all. Misty Fiords personnel who were key to the initiation and realization of this project include Jackie Canterbury and Don Fisher. Becky Nourse, Mark Jaqua, and Jan Peloskey all provided essential support during the field surveys. Also, Ketchikan Area staff Cole Crocker-Bedford, Michael Brown, and Richard Guhl provided indispensable support. Others outside of the Forest Service have provided assistance, without which this report would not be possible. Of particular note are Dr. David Murray, Dr. Barbara Murray, Carolyn Parker, and Al Batten of the University of Alaska Fairbanks Museum Herbarium. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................... -

Kachemak Bay Research Reserve: a Unit of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System

Kachemak Bay Ecological Characterization A Site Profile of the Kachemak Bay Research Reserve: A Unit of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System Compiled by Carmen Field and Coowe Walker Kachemak Bay Research Reserve Homer, Alaska Published by the Kachemak Bay Research Reserve Homer, Alaska 2003 Kachemak Bay Research Reserve Site Profile Contents Section Page Number About this document………………………………………………………………………………………………………… .4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Reserve ……………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Physical Environment Climate…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Ocean and Coasts…………………………………………………………………………………..11 Geomorphology and Soils……………………………………………………………………...17 Hydrology and Water Quality………………………………………………………………. 23 Marine Environment Introduction to Marine Environment……………………………………………………. 27 Intertidal Overview………………………………………………………………………………. 30 Tidal Salt Marshes………………………………………………………………………………….32 Mudflats and Beaches………………………………………………………………………… ….37 Sand, Gravel and Cobble Beaches………………………………………………………. .40 Rocky Intertidal……………………………………………………………………………………. 43 Eelgrass Beds………………………………………………………………………………………… 46 Subtidal Overview………………………………………………………………………………… 49 Midwater Communities…………………………………………………………………………. 51 Shell debris communities…………………………………………………………………….. 53 Subtidal soft bottom communities………………………………………………………. 54 Kelp Forests…………………………………………………….…………………………………….59 Terrestrial Environment…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 61 Human Dimension Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

A Second Annotated Checklist of Vascular Plants in Wells Gray Provincial Park and Vicinity, British Columbia, Canada

A second annotated checklist of vascular plants in Wells Gray Provincial Park and vicinity, British Columbia, Canada Version 1: April, 2011 Curtis R. Björk1 and Trevor Goward2 ENLICHENED CONSULTING LTD. Box 131, Clearwater, BC, V0E 1N0, Canada [email protected], [email protected] Vascular Plants in Wells Gray SUMMARY Wells Gray Provincial Park is a vast wilderness preserve situated in the mountains and highlands of south-central British Columbia. The first major floristic study of the vascular plants of Wells Gray and its vicinity was published in 1965 by Leena Hämet-Ahti, who documented 550 taxa, including a first Canadian record of Carex praeceptorium. The present study contributes nearly 500 additional taxa documented by us between 1976 and 2010 in connection with our personal explorations of the Clearwater Valley. The vascular flora of Wells Gray Park and vicinity now stands at 1046 taxa, including 881 native species and 165 species introduced from Eurasia and other portions of British Columbia. Wells Gray Park is notable both for the presence of numerous taxa (45) at or near the northern limits of their range, as well as for an unexpectedly high number of taxa (43) accorded conservation status by the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. Antennaria corymbosa has its only known Canadian locality within Wells Gray, while five additional species reported here are known in Canada from fewer than six localities. About a dozen unknown, possibly undescribed taxa have also been detected. Botanical inventory has thus far been confined to the southern portions of Wells Gray. Future studies in northern half of the park will certainly greatly increase our knowledge of the biological diversity safeguarded in this magnificent wilderness preserve. -

Parks Canada Mountain Guide

Mountain Guide 2014 - 2015 Your official guide to discovering Canada’s mountain national parks Également offert en français P. Zizka P. YOU’VE GOT TO SEE THIS! P. Zizka P. Welcome to the mountain national parks and national historic sites Exceptional places. Endless opportunities. On behalf of Canadians, Parks Canada protects a network of remarkable places from coast to coast to coast. The mountain national parks are more than just unique places to visit – they are experiences awaiting your discovery. Four of the mountain national parks – Banff, Jasper, Yoho and Kootenay – have been recognized by UNESCO as part of the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site, for the benefit and enjoyment of all nations. Among the attributes that warranted this designation were vast wilderness, floral and faunal diversity, outstanding natural beauty and features such as Lake Louise, Maligne Lake, the Columbia Icefield and the Burgess Shale. Waterton Lakes National Park is the Canadian portion of the internationally acclaimed Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. 2 For Destination Information What’s Inside... Banff Yoho National Historic Sites 4 Banff Visitor Centre: Yoho Visitor Centre: 403-762-1550 250-343-6783 Banff 6 Lake Louise Visitor Centre: Accommodations, restaurants and 403-522-3833 activities in Field: Banff Lake Louise Tourism: field.ca Icefields Parkway 13 403-762-8421 banfflakelouise.com Glacier and Yoho Jasper 16 Tourism Golden: Jasper 1-800-622-4653 Kootenay 21 Jasper Information Centre: tourismgolden.com