Programme Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

09 New Romanticisms, Complexities, Simplicities Student Copy

MSM CPP Survey EC 9. New… Romanticisms Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) ''In the beginning, I composed in a distinct style,'' Mr. Schnittke said in an interview in 1988, ''but as I see it now, my personality was not coming through. More recently, I have used many different styles, and quotations from many periods of musical history, but my own voice comes through them clearly now.’' He continued, ''It is not just eclecticism for its own sake. When I use elements of, say, Baroque music,'' he added, ''sometimes I'm tweaking the listener. And sometimes I'm thinking about earlier music as a beautiful way of writing that has disappeared and will never come back; and in that sense, it has a tragic feeling for me. I see no conflict in being both serious and comic in the same piece. In fact, I cannot have one without the other.’' NY Times obituary. Concerto Grosso no. 1 (1977) “a play of three spheres: the Baroque, the Modern and the Banal” (AS) String Quartet no. 2 (1980) Concerto for Mixed Chorus (1984-1985) Wolfgang Rihm (*1952) String Quartet No. 5 (1981-1983) Vigilia (2006) Jagden und Formen (1995-2001) MSM CPP Survey EC Morton Feldman (1926-1987) Rothko Chapel (1971) ‘In 1972, Heinz-Klaus Metzger obstreperously asked Feldman whether his music constituted a “mourning epilogue to murdered Yiddishkeit in Europe and dying Yiddishkeit in America.” Feldman answered: It’s not true; but at the same time I think there’s an aspect of my attitude about being a composer that is mourning—say, for example, the death of art. -

1996-1996 Achim Heidenreich

Neue Namen, alte Unbekannte Die EDITION ZEITGENÖSSISCHE MUSIK stärkte von Anfang an Individualität – nicht Lehrmeinungen (1986-1996) von Achim Heidenreich Seit 1986 gibt es die EDITION ZEITGENÖSSISCHE MUSIK (EDITION) des Deutschen Musikrats. Sie besteht aus musikalischen Porträts, in der Regel CDs, mit denen sich Komponistinnen und Komponisten, die das 40. Lebensjahr noch nicht erreicht haben sollten, häufig erstmals einer größeren Öffentlichkeit präsentieren können, sei es mit einem repräsentativen Querschnitt durch ihr Schaffen oder auch mit einem selbstgewählten Schwerpunkt. Ein größerer Bekanntheitsgrad und nicht selten weitere Aufträge sind die Folge. Auf diese Weise werden nicht nur die jungen Komponistinnen und Komponisten gefördert, auch wird das jeweils aktuelle Musikleben schwerpunktmäßig dokumentiert. Komponistinnen stellen insgesamt eher die Minderheit in den Veröffentlichungen dar. In der ersten Dekade bis 1996 waren es nur zwei: ADRIANA HÖLSZKY (*1953 / CD 1992) und BABETTE KOBLENZ (*1956 / CD 1990), inzwischen hat der Anteil deutlich zugenommen. Weitere Bewerbungsbedingungen um eine solche CD sind die deutsche Staatsbürgerschaft oder ein über eine längere Dauer in Deutschland liegender Lebensmittelpunkt. Wer also nur eine der beiden Vorgaben erfüllt, ist antragsberechtigt, die deutsche Staatsbürgerschaft ist nicht eine grundsätzliche Notwendigkeit. Wie die Geschichte der EDITION zeigt, wurden diese Antragsbedingungen sehr weise formuliert. Mit seiner hohen Orchester- und Opernhausdichte sowie seinen weitgehend studiengebührenfreien Studiengängen und der erstklassigen musikalischen Ausbildung an den Musikhochschulen gilt Deutschland weltweit nach wie vor als eine Art gelobtes Land, zumindest der klassischen und damit auch der zeitgenössischen und Neuen Musik. Entsprechend gestalten und entwickeln internationale Künstler das deutsche Musikleben entscheidend mit, was die CD-Reihe eindrucksvoll widerspiegelt. Die EDITION ist jedoch nicht nur eine reine Porträt-Reihe für Komponierende. -

Richard Toop

Shadows of Ideas: on Walter Zimmermann's Work[1] Richard Toop Introduction It may well seem strange to you that an Englishman who emigrated to Australia long ago should be invited here to talk about the work of a composer currently living in Berlin. At the time, it rather surprised me too. But perhaps it can be justified on two grounds. First, we have had personal contact for almost 30 years, and a kind of 'co-existence' that goes back even further. In the third volume of Stockhausen's Texte[2], as well as the Stockhausen entry in the first edition (1980) of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, there is a photo of Stockhausen playing one of the Aus den sieben Tagen texts at the 1969 Darmstadt Summer Courses. Behind him one can see a small part of the audience, including the composer Nicolaus A. Huber and the now celebrated Wagner specialist John Deathridge. Also in the picture are the 20-year-old Walter Zimmermann, and the 24-year-old Richard Toop. As far as I can remember, we didn't meet at the time, and didn't get to talk to one another. But 4 years later, once I was Stockhausen's teaching assistant at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Cologne, we were in regular contact. Walter's flat was barely 500 m. away from mine, which was where I gave my classes. But even this short distance encapsulated some basic social divisions. Where I lived, in Kleverstrasse, there was a modestly endowed Polish Consulate to the left of my flat, and above it, according to the house owner, was a very discreetly run brothel. -

Tempo CLARENCE BARLOW's TECHNIQUE OF

Tempo http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM Additional services for Tempo: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here CLARENCE BARLOW'S TECHNIQUE OF ‘SYNTHRUMENTATION’ AND ITS USE IN IM JANUAR AM NIL Tom Rojo Poller Tempo / Volume 69 / Issue 271 / January 2015, pp 7 - 23 DOI: 10.1017/S0040298214000898, Published online: 02 January 2015 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0040298214000898 How to cite this article: Tom Rojo Poller (2015). CLARENCE BARLOW'S TECHNIQUE OF ‘SYNTHRUMENTATION’ AND ITS USE IN IM JANUAR AM NIL. Tempo, 69, pp 7-23 doi:10.1017/S0040298214000898 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM, IP address: 77.12.24.28 on 22 Jan 2015 TEMPO 69 (271) 7–23 © 2015 Cambridge University Press 7 doi:10.1017/S0040298214000898 clarence barlow’s technique of ‘synthrumentation’ and its use in im januar am nil Tom Rojo Poller Abstract: ‘Synthrumentation’ is a technique for the resynthesis of speech with acoustic instruments developed by the composer Clarence Barlow in the early 1980s. Over the past decade instru- mental speech synthesis has been Clarence Barlow. Photo by Birgit thematised by a diverse range of Faustmann. Used by permission of composers (e.g. Peter Ablinger Clarence Barlow. and Jonathan Harvey); however, Barlow’s work is rarely accorded the credit it deserves for the pioneering role it played in this field. This article seeks to explain the basic mechanics of the synthrumentation technique and to demonstrate its practical application through an analysis of Barlow’sensemblepieceIm Januar am Nil composed between 1981 and 1984. -

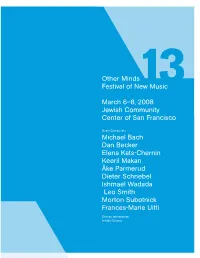

Other Minds 13 Program

Other Minds Festival of New Music March 6–8, 2008 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Guest Composers Michael Bach Dan Becker Elena Kats-Chernin Keeril Makan Åke Parmerud Dieter Schnebel Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith Morton Subotnick Frances-Marie Uitti Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director 34 12 16 B 7 19 15 A 2 36 1 Other Minds, in association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the Eugene and Elinor Friend Center for the Arts at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, presents Other Minds 13 Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director Jewish Community Center of San Francisco March 6-7-8, 2008 Table of Contents 3 Message from the Artistic Director 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction 6 Concert 1 7 Concert 1 Program Notes 10 Concert 2 11 Concert 2 Program Notes 14 Concert 3 15 Concert 3 Program Notes 20 Other Minds 13 Composers 24 About Other Minds Other Minds 13 Festival Staff 25 Other Minds 13 Performers 28 Festival Supporters A Gathering of Other Minds Program Design by Leigh Okies. Layout and editing by Adam Fong. © 2008 Other Minds. All Rights Reserved. The Djerassi Resident Artists Program is a proud co-sponsor of Other Minds Festival XIII The mission of the Djerassi Resident Artists Program is to support and enhance the creativity of artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection, and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty, and to preserve the land upon which the Program is situated. The Djerassi Program annually welcomes the Other Minds Festival composers for a five-day residency for collegial interaction and preparation prior to their concert performances in San Francisco. -

"Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen : Moments from a Double Portrait"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Érudit Article "Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen : moments from a double portrait" Bob Gilmore Circuit : musiques contemporaines, vol. 19, n° 2, 2009, p. 35-49. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037449ar DOI: 10.7202/037449ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 02:54 Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen : moments from a double portrait Bob Gilmore 1. Introduction : “le plus grand musicien actuel…” “Dans ses œuvres Stockhausen veut élargir le champ de la conscience humaine, il veut nous montrer des planètes nouvelles,” wrote Claude Vivier in December 1978 of the music of his former teacher. “Mais l’homme Stockhausen qui est-il? Dans Momente, au moment “KK” (K : Klang/son et K : Karlheinz) il nous offre son autoportrait : un grand appel solitaire et triste ; son urgence de dire est issue d’une grande solitude, d’un besoin de communiquer avec le reste du cosmos”.1 It is striking that these last words seem to apply equally 1. -

Kevin Volans' She Who Sleeps Witha Small Blanket: an Examination of the Intentions, Reactions, Musical Influences, and Idiomatic Implications

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2011 Kevin Volans' She Who Sleeps Witha Small Blanket: An Examination of the Intentions, Reactions, Musical Influences, and Idiomatic Implications Peter D. Breithaupt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Breithaupt, Peter D., "Kevin Volans' She Who Sleeps Witha Small Blanket: An Examination of the Intentions, Reactions, Musical Influences, and Idiomatic Implications" (2011). Master's Theses. 388. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/388 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KEVIN VOLANS' SHE WHO SLEEPS WITHA SMALL BLANKET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE INTENTIONS, REACTIONS, MUSICAL INFLUENCES, AND IDIOMATIC IMPLICATIONS by Peter D. Breithaupt A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofThe Graduate College in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofArts School ofMusic Advisor: Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2011 KEVIN VOLANS' SHE WHO SLEEPS WITHA SMALL BLANKET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE INTENTIONS, REACTIONS, MUSICAL INFLUENCES, AND IDIOMATIC IMPLICATIONS Peter D. Breithaupt, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2011 Using and expanding upon a theoretical model for examining the meaning of music presented by ethnomusicologist Timothy Taylor, one of the leading scholars on composer Kevin Volans and his music, this research will attempt to properly position Volans' percussion solo, She Who Sleeps witha Small Blanket, composed in 1985, within Volans' African Paraphrase classification. -

Programme Notes

Something New, Something Old, Something Else Philip Thomas - piano J.S.Bach Prelude and Fugue in C major (book 1) Prelude and Fugue in F major (book 2) A.Clementi Variazioni su B.A.C.H. (1984) R.Emsley Flow Form (1986-7) M.Finnissy Ives (1974) My Bonny Boy (1977) (from English Country Tunes ) C.Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) --- INTERVAL --- R.Emsley for piano 13 (2003) ** world premiere** Tonight's concert is the first of two this season - and hopefully of more in the future - grouped together under the title Something New, Something Old, Something Else . The primary intention is that a major new work is commissioned from a composer whose music I find to be radical, original and ultimately inspiring. Then, an older work by the same composer is chosen to go alongside the new work and the programme is completed by works by other composers, from any musical period or style, that might demonstrate connections, traces, influences, or even disparities. These works have been selected after discussions between the composers and myself. The two composers who have written new works this year - Richard Emsley for tonight's concert and Christopher Fox for the concert on 24th February 2004 - are composers whose music I first played in 2001 as part of my John Cage and Twenty-first Century Britain series at the Mappin Art Gallery. Since then I have heard and played more of their music in other contexts and have come to appreciate it in greater measure. Their music, though very different, beguiles, entrances and intrigues me. -

The Preservation of Subjectivity Through Form: the Radical Restructuring of Disintegrated Material in the Music of Gerald Barry, Kevin Volans and Raymond Deane

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2014-5 The Preservation Of Subjectivity Through Form: The Radical Restructuring Of Disintegrated Material In The Music Of Gerald Barry, Kevin Volans And Raymond Deane. Adrian Smith Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Composition Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Smith, A. (2014) The preservation of subjectivity through form: the radical restructuring of disintegrated material in the music of Gerald Barry, Kevin Volans and Raymond Deane.Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin.doi:10.21427/D7401T This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License THE PRESERVATION OF SUBJECTIVITY THROUGH FORM: THE RADICAL RESTRUCTURING OF DISINTEGRATED MATERIAL IN THE MUSIC OF GERALD BARRY, KEVIN VOLANS AND RAYMOND DEANE Adrian Smith BMus Submitted for the qualification of PhD Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald May 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis examines Adorno’s concept of ‘disintegrated musical material’ and applies it to the work of the Irish composers Raymond Deane (b. 1953), Gerald Barry (b. 1952) and Kevin Volans (b. 1949). Although all three of these composers have expressed firm commitments to the ideal of creating new and radical works, much of the material in their music is composed of elements abstracted from the tonal past. -

New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival __

NEW YORK CITY ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC FESTIVAL __ JUNE 2-8, 2014 __ www.nycemf.org CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S WELCOME 5 FESTIVAL SCHEDULE 6 COMMITTEE & STAFF 8 PROGRAMS AND NOTES 9 INSTALLATIONS 62 COMPOSERS 63 PERFORMERS 97 WORKSHOP 107 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THE CARY NEW MUSIC PERFORMANCE FUND DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Welcome to NYCEMF 2014! On behalf of the Steering Committee, it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2014 New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival. We have an exciting program of 31 concerts over seven days at the Abrons Arts Center in new York City. We hope that you will enjoy all of them! We would first like to express our sincere appreciation to the following people and organizations who have contributed to us this year, in particular: - The Cary New Music Performance Trust - The Genelec corporation, for providing us with loudspeakers to enable us to play all concerts in full surround sound - Fractured Atlas/Rocket Hub - The staff of the Abrons Arts Center, who have helped enormously in the presentation of our concerts - East Carolina University, New York University, Queens College C.U.N.Y., Ramapo College of New Jersey, and the State University of New York at Stony Brook, for lending us equipment and facilities - Harvestworks, Inc. For hosting a reception, and for their advice and guidance - The Steering Committee, who spent numerous hours in planning all aspects of the events - All the composers who submitted the music that we will be playing. None of this could have happened without their support Hubert Howe -

Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen : Moments from a Double Portrait Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen: Moments from a Double Portrait Bob Gilmore

Document generated on 09/28/2021 1:38 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen : moments from a double portrait Claude Vivier and Karlheinz Stockhausen: moments from a double portrait Bob Gilmore Stockhausen au Québec Article abstract Volume 19, Number 2, 2009 That Karlheinz Stockhausen played a crucial role in the musical development of the young Claude Vivier is beyond question. In an autobiographical note URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037449ar written in 1975, Vivier noted: “Born in Montreal in 1948. Born to music with DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037449ar Gilles Tremblay in 1968. Born to composition with Stockhausen in 1972. Indeed, the widespread view is that, during the years he studied formally with See table of contents Stockhausen at the Hochschule für Musik in Cologne (1972-74), Vivier hero-worshipped the German composer. Widely regarded as one of the leading figures of the international musical avant-garde, Stockhausen had held for two decades a position that, by the time Vivier began formal studies with him, was Publisher(s) under assault. The whole system of values for which he stood, musical and Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal otherwise, was being questioned to its foundations, even, in some quarters, reviled and demonised. The relationship between the young Vivier and his distinguished teacher is therefore a complex one. While Vivier evidently fell ISSN powerfully under the sway of Stockhausen’s music and ideas and his 1183-1693 (print) charismatic and domineering personality, this article explores the effect on 1488-9692 (digital) him of the changing attitudes toward Stockhausen as the 1970s wore on. -

Croft Lachenmann Taylor Zimmerman

Philip Thomas - piano ...du second infini (2000) John Croft Serynade (1998/2000) Helmut Lachenmann ---- INTERVAL ---- Patterns 1 (1973) Failure (2000) Mark R. Taylor Wüstenwanderung (1986) Walter Zimmermann This evening's concert presents a defiantly avant-garde selection of music by four composers, from Germany and the U.K., who celebrate the imperative to create new contexts in which to stimulate fresh musical and artistic thought. Avoiding recent (and not-so-recent) trends and clichés, each composer sets forth a situation which is pursued rigorously, intelligently, and unsentimentally. From such a stance is revealed a fresh spring of creativity which captivates us, challenging us to reconsider our listening and perceptual habits, enlarging our experience and leading to a furthering of our intellectual and sensual capacities. The first half features two pieces which are concerned with the prolongation and tracing of the created (attacked) sound. In their different ways, both Lachenmann and Croft explore and focus upon the dialectic between the percussive nature of the piano and the after-life of attack upon its strings. Both composers attempt to get to the truth of the nature of the piano, embracing its limitations and capabilities as an instrument upon which so much depends on the initial attack and from which the potential variety of timbre and manner of decay appears incapable of being exhausted. The second half of the programme explores a different arena of compositional thought - that of process. The extreme simplicity and cool objectivity of Mark R. Taylor's early work, Patterns 1, as with the short pieces making up Failure, reveals, to the listener willing to 'tune in', a greater complexity than the material and elemental process would suggest.