Of Venice in the Work of F. Hopkinson Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Venetian June

A Venetian June by Anna Fuller A Venetian June I Venice "Si, Signore!" The gondola stirred gently, as with a long, quiet breath, and a moment later it had pushed its way out from among the thronging craft at the steps of the railway quay, and was gliding with its own leisurely motion across the sunlit expanse of the broad Canal. As the prow of the slender black bark entered a narrow side-canal and pursued its way between frowning walls and under low arched bridges,—as the deep resonant cry of the gondolier rang out, and an answer came like an echo from the hidden recesses of a mysterious watery crossway, the spirit of Venice drew near to the three travellers, in whose minds its strange and exquisite suggestion was received with varying susceptibility. To Pauline Beverly, sitting enthroned among the gondola cushions, this was the fulfilment of a dream, and she accepted it with unquestioning delight; her sister May, at the bar of whose youthful judgment each wonder of Europe was in turn a petitioner for approval, bestowed a far more critical attention upon the time-worn palaces and the darkly doubtful water at their base; while to Uncle Dan, sitting stiffly upright upon the little one-armed chair in front of them, Venice, though a regularly recurrent experience, was also a memory,—a memory fraught with some sort of emotion, if one might judge by the severe indifference which the old soldier brought to bear upon the situation. Colonel Steele was never effusive, yet a careful observer might have detected in his voice and manner, as he gave his orders to the gondolier, the peculiar cut-and-dried quality which he affected when he was afraid of being found out. -

Molesey Boat Club

RESOLUTE Molesey Men HOCR 2017 Event 6 - 9:50 AM Men’s Senior Masters 8 (50+) Position Name History Cox Adrian Ellison GB Olympic Gold 4+ in 1984 LA Olympics and multiple world medalist Stroke Magnus Burbanks GB multiple national champion at sculling 7 Ian McNuff GB Olympic/world bronzes 4- 1978-80 6 Martin Cross GB Olympic Gold 4+ 1984 LA Olympics, Olympic Bronze 1980 4- Moscow; multiple world medalist 5 Paul Wright GB national champion and Henley winner 4 John Beattie GB Olympic/world Bronzes 4- 1978-80, 1984 GB Olympian LA 3 Farrell Mossop GB multiple International 2 Paul Reynolds GB multiple International Bow Tony Brook NZ world champion and silver 8+ Event 26 - 3:24 PM Men’s Masters 8 (40+) Position Name History Cox Phelan Hill GB International - Gold Olympic 8+ 2016 Rio Stroke Artour Samsanov US International and 2004 Olympian-Athens 7 Ed Bellamy GB International and Oxford President 6 Tom Solesbury GB International, Olympian 2004 & 2008 5 Bobby Thatcher GB Olympian and world Silver 8+ 4 Dave Gillard GB International and Cambridge 3 Andrew Brennan US International and medalist 2 Tom Anderson Oxford Bow Tom Middleton GB Olympian LM2x Sydney 2000, Silver medalist in LM8+, 2000 Roster Bios for Event 6 - 9:50 AM Men’s Senior Masters 8 (50+) Cox: Adrian Ellison - World champ bronze x2 (M2+ 1981, M8 1989), Olympic gold (M4+ 1984) Adrian Ellison was born on 11 September 1958 and is a retired English rowing cox. He coxed the men's four which brought Steve Redgrave his first Olympic gold in Los Angeles in 1984. -

Sunny Boats Private Limited

+91-8048718675 Sunny Boats Private Limited https://www.indiamart.com/sunny-watersports/ Being a reckoned name, we are engaged in manufacturing, exporting and importing Water Sports Equipment and Tourist Boats. Offered range of boats has gained huge appreciation as having exceptional stability & tracking property. About Us The year was 1996 when we established our firm "Sunny Water Sports Products Private Limited", and began our journey as one of the eminent manufacturers, exporters and importers of Water Sports Equipment and Tourist Boats. These boats are available in various models be it required for trainers, riders, explorers or beginners, in several types. Designing & development task is done at our world- class infrastructure keeping in consideration the flawless configuration of these products. Depending upon the needs of users, we have assorted Kayaks – FRP & Carbon Kevlars, Rowing Shells – FRP & Carbon Kevlars and Training Boats, under our array of boats. Used prominently at water sports centers, at bird & wildlife sanctuaries, parks, lakes, tourist sports, these boats are offered with the assurance of maximal stability & manageability, that is their property to be carried out easily and being impact resistant. The complete manufacturing procedure is conducted & regulated under the strict surveillance of our expert professionals, following & maintaining industry set standards. Our workplace is organized & coordinated availed with advanced range of machinery & tools. In this process, we are supported by our competent professionals, -

Sydney Rowing Club

Sydney Rowing Club Saturday, 21 February 2009 Sydney International Regatta Centre Penrith Lakes, NSW 1 SB4 4+ School 4th Four ........................................................................... Final 2 SB3 4+ School 3rd Four ........................................................................... Final 3 SB2 4+ School 2nd Four .......................................................................... Final 4 SB1 4+ School 1st Four ............................................................................ Final 5 SB3 8+ School Third Eight ....................................................................... Final 6 WU19/21 2x Women's Under 19 / Under 21 Double Scull ............................... Final 7 MU19/21 2- Men's Under 19 / Under 21 Pair .................................................. Final 8 WO/U23 4- Womens Open/Under 23 Coxless Four ....................................... Final 9 MO/L/U23 4x Mens Open/Lwt/Under 23 Quad Scull ......................................... Final 10 MU17 2x Men's Under 17 Double Scull ...................................................... Final 11 VW 2- Women's Masters Pair ................................................................. Final 12 VM 4+ Men's Masters Coxed Four .......................................................... Final 13 VM 4- Men's Masters Coxless Four ....................................................... Final 14 SB2 8+ School 2nd Eight .......................................................................... Final 15 SB1 8+ School 1st Eight .......................................................................... -

July 2019 News

JULY 2019 NEWS Above: Henley Royal Regatta scene with our Wyfold crew in the foreground News covered this month • Ria Thompson takes gold at World Under 23 Championships • Gold and Bronze for Mercantile at Under 23 Championships • Racing begins tonight in the World Under 23 Championships • Celebration of lives – Martin Owen and Libby Douglas • Vale Martin Owen • Vale Libby Douglas • WC3 – Australia and Mercs dominate • WC3 – All Mercs members through semi finals and reps on Saturday • WC3 – time trials replace heats • World Cup 3 – Friday heats postponed due to weather • Mercs at World Cup 3 – Racing starts Friday • Trustees announce more grants • Australian Under 23 Men’s eight announced – 2 more Mercs members added to the team • Mercantile mourns the loss of Nick Garratt AM • Henley Day 5 – Sunday • Henley Day 4 – Saturday • Henley Day 3 – Friday • Henley Day 2 – Thursday • Henley Day 1 -Wednesday • Henley Royal Regatta preview • Yet more Mercs members in the Australian Under 23 team • Foundation trustees announce further grants from the Cooper Fund • From the Archives – Club fundraising in 1883 ______________________________________________________________________________ Ria Thompson takes gold at World Under 23 Championships Published 29th July 2019 Ria Thompson, who rowed for Mercantile before moving to Queensland to study, won the under 23 single scull last night in a superb race. She started relatively slowly and was in fourth place throughout the first 1000m. She then did a powerful third 500m rowing through all but the leading American sculler. Ria had the momentum and then broke the American is the final stages of the race. The men’s eight raced their final and finished sixth. -

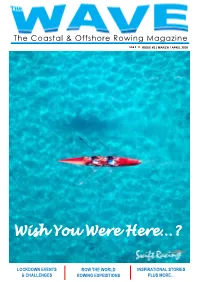

Wish You Were Here…?

The Coastal & Offshore Rowing Magazine ISSUE #3 | MARCH / APRIL 2020 Wish You Were Here…? LOCKDOWN EVENTS ROW THE WORLD INSPIRATIONAL STORIES & CHALLENGES ROWING EXPEDITIONS PLUS MORE… WELCOME ISSUE #3 | WELCOME Welcome to Issue #3 of The Wave – the Coastal and We also bring you Rannoch’s Row The World and their Offshore Magazine. new flagship boat Roxy and her expeditions which you can be a part of. Due to the strange circumstances we find ourselves in, We also want to get you dreaming of a rowing holiday, we have been beached in lockdown with many events so in this issue we will be introducing you to the Coastal cancelled but that hasn’t stopped the challenges! & Gig Rowing Camp 2021. In this issue, we’re not going to dwell on the COVID-19 The Wave Rowing website will become soon feature situation or recommending workouts – there’s plenty of some exciting content so stay tuned! that already on the internet and filling up your social media feeds! We have also omitted the news section. Thank you for all your kind comments and feedback in relation to Issue #2 and the reception of The Wave Instead we wanted to have a positive feel to the issue Rowing in general. It really means a lot and love to hear so we are focusing on the events and achievements your feedback in order to help it grow. that people are undertaking in the Coastal & Offshore Is something missing or looks like we forgot to mention? community. The innovations of some clubs in hosting We need you to send us your press releases including events and clubs coming together to compete against photos so we can feature this for you! each other. -

“ I'm Going to My Kid's Regatta. Now What?”

“ I’m going to my kid’s regatta. Now what?” Welcome to the world of not knowing what your rower is talking about…shell, rigging, coxswain, catching a “crab”, feathering, “power 10”…! And don’t forget the regatta…what am I supposed to be watching for? And where? And how do I know if they won? Or not? Where are they? Well, we’ve all been there. And we’re all still learning. To help parents just starting out, we’ve pulled together some information about rowing and regatta basics. Adopted from USRowing (with editing and additions): First, a little history. The first reference to a “regata” appeared in 1274, in some documents from Venice. (Impress your rower with that…) The first known ‘modern’ rowing races began from competition among the professional watermen that provided ferry and taxi service on the River Thames in London, drawing increasingly larger crowds of spectators. The sport grew steadily, spreading throughout Europe, and eventually into the larger port cities of North America. Though initially a male-dominated sport (what’s new?), women’s rowing can be traced back to the 19th century. An image of a women’s double scull race made the cover of Harper’s Weekly in 1870. In 1892, four young women from San Diego, CA started ZLAC Row Club, the oldest all women’s rowing club in the world. Sculling and Sweep Rowing Athletes with two oars – one in each hand – are scullers. There are three sculling events: the single – 1x (one person), the double – 2x (two) and the quad – 4x (four). -

Chapter 1 History S

Chapter 1 History S. Volianitis and N.H. Secher “When one rows, it’s not the rowing which moves the neither the Olympic nor the Spartathlon games ship: rowing is only a magical ceremony by means of included on-water competitions. The earliest record which one compels a demon to move the ship.” of a rowing race, The Aeneiad, written between 30 Nietzsche and 19 BC by Virgil, describes a competition in the Greek fl eet that was in Troy around 800 BC. Also, there is evidence that more than 100 boats and 1900 oarsmen participated in rowing regattas organized Development of rowing by the Roman Emperors Augustus and Claudius. A reconstruction of an Athenian trieres (three rows of oars; Fig. 1.1), the warship of the classical world, In parallel with the two milestones in the 37 m long and 5.5 m wide with up to 170 oarsmen, development of human transportation on land — named Olympias, was built in Piraeus in 1987 and the domestication of animals and the discovery of was used in the torch relay of the 2004 Olympic the wheel — the construction of water-borne vessels Games in Athens (Fig. 1.2). enabled the transport of large amounts of goods Because modern humans are on average long before the development of extensive road net- approximately 20 cm taller than ancient Greeks, works. The effective use of leverage which facilitates the construction of a craft with the precise dimen- propulsion of even large boats and ships indepen- sions of the ancient vessel led to cramped rowing dent of the direction of the wind established the oar conditions and, consequently, restrictions on the as the most cost-effective means of transportation. -

Boathouse Chatter Issue 8

February 2021 - Issue 8 BOATHOUSE CHATTER ➢ Welcome Welcome to Boathouse Chatter. Boris Johnson’s road map to take the country out of ‘lockdown’ has been published and provides a glimmer of hope that we will be back on the water in the not too Thanks for all the people who have distant future which is great news. The current direction of travel suggests that contributed to the Newsletter. You outdoor sport will be allowed to start again around the 29th March 2021 – just as the have made it a very full and varied weather is starting to improve! At this stage, all government and British Rowing issue. It would be great if we could guidance is subject to infection levels continuing to fall and vaccination levels keep the contributions coming in continuing to rise. The Trustees are keeping a close eye on the unfolding guidance and for future issues. Please let us know will send out details of our own return to rowing as we get closer to the end of the your news and what you’re doing month. to get by – stay in touch! Our Annual General Meeting will be held via zoom on Sunday 28th March 2021. Please keep an eye on the email forum and the website forum for regular updates and let us know if you plan to attend by emailing [email protected]. Please send your news to [email protected] by Sunday 21st March 2021. Next The Trustees continue to meet regularly. If you have any queries or concerns, please issue Sunday 28th March 2021 contact Dan directly at [email protected] . -

Rowing Instruction Guide 2018

Founded 26 May 1848 Patroness: H.K.H. Prinses Beatrix Honorary Chairman: the Mayor of Amsterdam KONINKLIJKE AMSTERDAMSCHE ROEI – EN ZEILVEREENIGING ‘DE HOOP’ INSTRUCTION GUIDE for starting rowers Weesperzijde 1046a, 1091 EH Amsterdam, telefoon: 020 – 6657844 [email protected] www.karzvdehoop.nl CONTENTS 1. ROWING TECHNIQUE 1.1. Sculling (two oars) 1.2. Sweep rowing (one oar) 2. COMMANDS 2.1. Bringing the boat in and out 2.2. Getting into the boat 2.3. Move away from the pontoon 2.4. Landing 2.5. Getting out of the boat 2.6. Reducing speed and stopping 2.7. Backing (reverse rowing) 2.8. Changing direction (by the rowers) 2.9. Passing obstacles 2.10. Draw pressure 3. ROWING EXAMS 3.1. Permissions 3.2. Requirements for S-I and B-I exam 3.3. Requirements for S-II and B-II exam 3.4. Requirement for S-III and B-III exam 3.5. Questions about boat components 3.6. Questions about navigation rules for rowers 4. ROWING MATERIAL 4.1. Boat components 4.2. Oars 4.3. Boat prices 5. BOAT TYPES 5.1. Racing material 5.2. Touring material 5.3. Material for instruction and training 6. ROWING FROM THE DOCK AND LANDING 6.1. Rowing away from the dock 6.2. Rowing away with strong wind 6.3. Landing 6.4. Landing with strong wind 7. USEFUL TIPS FOR COXING 8. NAVIGATION RULES FOR ROWERS 8.1. Important navigation rules from BPR 8.2. Sound signals 8.3. Illumination 8.4. Bridges 2 Rowing Instruction Guide KAR&ZV De Hoop - November 2018 1. -

Ride the Tide: This Summer, There Are Many Ways to Explore the Providence River

Ride the Tide: This summer, there are many ways to explore the Providence River Marcello; photo credit: Alison O’Donnell Providence is a hopping city — usually. We find ourselves a bit limited this summer, because COVID, but because Phase 2 reopened some businesses and parks in the state, we once again have recreation options on the water. In fact, more options than ever before! Matthew “Marcello” Haynes became a gondolier in 1999, something he’d always wanted to do. You’ve likely seen him rowing down the river at a WaterFire event. In 2007, he bought the company La Gondola. Right about that time, Tom McGinn bought the Providence River Boat Company. Then, in spring 2017, as Marcello describes it, “I, Tom and his partner, Kristin Stone, sat for a pint one night and decided we’d like to open a kayak company. So we’ve been contemporaries on the river for quite some time.” Together they started Providence Kayak, now in its fourth season. Venn diagram aside, whether you’re looking to ride the Providence River in a gondola, kayak or river boat, they’ve got ya covered. They started with a dozen kayaks and built up from there. Ever expanding to accommodate their customers, this year includes additional choices. “We have 17 kayaks on the water right now,” says Marcello, “and we’re working on getting a fleet of ‘pedal’ boats on the water, which hold up to four passengers. Instead of having a flywheel, they have propellers attached to each pedaling mechanism,” explains the former physics teacher. -

Download the Learn-To-Row Brochure

Want to learn how to row but Learn to Scull 101 don't know how to get started? Six 2-hour Saturday/Sunday group rows in a quadruple scull with two students and two experienced instructors or a double Learn the sport's fundamentals scull with one student and one instructor. Experience the with our exciting new Learn To rhythm and beauty of team boat rowing. Sessions will be held Row (LTR) options. Prior rowing from 10AM-noon starting May 18th & May 19th and experience is not required. concluding June 8th & June 9th. (Note: Classes will not be held Memorial Day weekend.) Classes are held at Island MetroPark boat house and on Learn to Scull 102 the beautiful Great Miami River Six 2-hour Saturday/Sunday sessions in a single scull with instruction and demonstration by an experienced rower and 104 E Helena St additional coaching from a safety launch. Step up to the Dayton, Ohio challenge of rowing a single with a group. Sessions will be held from 10AM-noon starting June 15th & June 16th and concluding June 29th & June 30th. Learn to Scull 101 is encouraged but not required. LTS101 participants may sign up for free. Learn to Sweep Six 2-hour Tuesday/Thursday group rows in an 8+ with four students, four experienced rowers, and a coxswain. The sweep 8+ is the biggest and fastest boat you see at rowing events. Sessions will be held from 6-8PM June 4th & June 6th and concluding June 18th & June 20th. LTS101 and LTS102 participants who want to experience sweep may sign up for free.