Love-Triangles and the Structure of Fahrenheit 451: Creating Contrast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher (Last Name) Title and Author of Book Brief Summary Secura the Hate You Give--Angie Thomas “Sixteen-Year-Old Star

Teacher Title and author Brief summary (Last of book Name) Secura The Hate You “Sixteen-year-old Starr Carter moves between two worlds: Give--Angie the poor neighborhood where she lives and the fancy Thomas suburban prep school she attends. The uneasy balance between these worlds is shattered when Starr witnesses the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend Khalil at the hands of a police officer. Khalil was unarmed.What everyone wants to know is: what really went down that night? And the only person alive who can answer that is Starr.” This book addresses controversial issues of interest to many adolescents and includes scenes and language that reflect mature content. Imbarus Out of the Dr. Aura Imbarus vividly details Christmas Day 1989, Transylvania when she, her parents and hundreds of shoppers drew Night--Aura sudden sniper fire as Romania descended into the Imbarus violence of a revolution that challenged one of the most draconian regimes in the Soviet bloc. Aura recalls a grisly execution that rocked the world and led to five harrowing days of bloody chaos as she and her family struggled to survive. The next day, Communist-controlled television released photos showing that dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife had been assassinated-though many Romanians, the author included, believed the executions had been staged since Ceausescu was known for using stand-ins to pose for him. Nevertheless, Aura tries to convince herself that life post-revolution will be different, but little changes. On May 7, 1997, with two pieces of luggage and a powerful dream, Aura and her new husband flee to America. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Promethean Rebellion in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit

Vol. 4 (2012) | pp. 1-20 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_AMAL.2012.v4.40586 PROMETHEAN REBELLION IN RAY BRADBURY’S FAHRENHEIT 451: THE PROTAGONIST’S QUEST FERNANDA LUÍSA FENEJA ISLA CAMPUS LISBOA – LAUREATE INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITIES ULICES/CEAUL (UNIVERSITY OF LISBON CENTRE FOR ENGLISH STUDIES) [email protected] Article received on 01.02.2012 Accepted on 14.08.2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to reflect on the role of myth in science fiction narrative, namely on the specific forms it may take in utopian/dystopian fiction, such as Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury. The personal development of the main character, Guy Montag, constitutes the focus of this analysis, by which we aim to shed some light on the relation between the meaning of the novel and the Promethean features he evinces in the context of a dystopian novel. The symbolic power of fire and of books is also of core relevance to this study, not only because they highlight the hero’s inheritance of the Promethean myth, but also because they provide a deeper insight into the exegetic possibilities of dystopian fiction. KEYWORDS Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, Prometheus myth, rebellion, dystopia, science fiction, protagonist. 1. INTRODUCTION Social criticism has been closely associated with science fiction narrative, inasmuch as the alternative worlds depicted often draw on critical aspects of contemporary society or history, in order to metaphorically highlight its frailties. Resorting to sophisticated technological apparatus, most science fiction texts manage thereby to attain a symbolic level of significance that is somehow reinforced by the apparent gap between the real, recognizable world disclosed in the texts, and the narrative settings and chronotopes framing them. -

Portsmouth Christian Academy at Dover Upper School Recommended Summer Reading June 2013

Portsmouth Christian Academy at Dover Upper School Recommended Summer Reading June 2013 Portsmouth Christian Academy’s Upper School library recommends the following books for your summer reading enjoyment and to keep your reading skills sharp for the coming year! You’ll find various genres represented here: current popular titles and classic works, fiction and nonfiction, Christian and secular titles: in other words, something for every reading interest, so enjoy! Note: Different books are appropriate for and appeal to different ages, reading levels, personalities, interests, beliefs and lifestyles. As always, please use both your own discretion and your parents’ guidance in choosing what to read. NOTE: In this year’s reading list, articles on dystopian fiction and on the author Ray Bradbury are followed by the general reading list. Dystopian Fiction: I want a book like The Hunger Games! Suggestions: Card, Orson Scott. Ender’s Game and Ender in Exile. Cashore, Kristen. Graceling and Bitterblue. Condie, Ally. Matched, Crossed, Reached. Dashner, James. The Maze Runner, The Scorch Trials, Death Cure, The Kill Order. Lowry, Lois. The Giver, Gathering Blue, Messenger, Son. Lu, Marie. Legend, Prodigy. Roth, Veronica. Divergent, Insurgent. 1 Suzanne Collins’ runaway bestseller trilogy The Hunger Games was a product of the author’s love for military history and also her fascination with the gladiators of ancient Rome. The admittedly horrifying idea of children being forced to fight to the death, or otherwise manipulated in a dystopian society, finds echoes in other books published before and since, such as Ender’s Game and Ender in Exile by Orson Scott Card. -

Zen in the Art of Writing – Ray Bradbury

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ray Bradbury has published some twenty-seven books—novels, stories, plays, essays, and poems—since his first story appeared when he was twenty years old. He began writing for the movies in 1952—with the script for his own Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The next year he wrote the screenplays for It Came from Outer Space and Moby Dick. And in 1961 he wrote Orson Welles's narration for King of Kings. Films have been made of his "The Picasso Summer," The Illustrated Man, Fahrenheit 451, The Mar- tian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the short animated film Icarus Montgolfier Wright, based on his story of the history of flight, was nominated for an Academy Award. Since 1985 he has adapted his stories for "The Ray Bradbury Theater" on USA Cable television. ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING RAY BRADBURY JOSHUA ODELL EDITIONS SANTA BARBARA 1996 Copyright © 1994 Ray Bradbury Enterprises. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments to reprint may be found on page 165. Published by Joshua Odell Editions Post Office Box 2158, Santa Barbara, CA 93120 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bradbury, Ray, 1920— Zen in the art of writing. 1. Bradbury, Ray, 1920- —Authorship. 2. Creative ability.3. Authorship. 4. Zen Buddhism. I. Title. PS3503. 167478 1989 808'.os 89-25381 ISBN 1-877741-09-4 Printed in the United States of America. Designed by The Sarabande Press TO MY FINEST TEACHER, JENNET JOHNSON, WITH LOVE CONTENTS PREFACE xi THE JOY OF WRITING 3 RUN FAST, STAND STILL, OR, THE THING AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, OR, NEW GHOSTS FROM OLD MINDS 13 HOW TO KEEP AND FEED A MUSE 31 DRUNK, AND IN CHARGE OF A BICYCLE 49 INVESTING DIMES: FAHRENHEIT 451 69 JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: DANDELION WINE 79 THE LONG ROAD TO MARS 91 ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS 99 THE SECRET MIND 111 SHOOTING HAIKU IN A BARREL 125 ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING 139 . -

Ray Bradbury Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8mw2pqh Online items available Willis E. McNelly Science Fiction Collection: Ray Bradbury papers Finding aid created by University Archives and Special Collections staff using RecordEXPRESS California State University, Fullerton. University Archives and Special Collections 800 N. State College Blvd. Pollak Library South, Room 352 Fullerton, California 92834-4150 (657) 278-4751 [email protected] http://www.library.fullerton.edu/ 2021 Willis E. McNelly Science Fiction SC-06-RB 1 Collection: Ray Bradbury papers Descriptive Summary Title: Willis E. McNelly Science Fiction Collection: Ray Bradbury papers Dates: 1946 - 1981 Collection Number: SC-06-RB Creator/Collector: Extent: 6 boxes Online items available http://archives.fullerton.edu/repositories/5/resources/60 Repository: California State University, Fullerton. University Archives and Special Collections Fullerton, California 92834-4150 Abstract: The Ray Bradbury papers contains original manuscripts of The Fireman, Fahrenheit 451, short stories, and first editions donated and signed by Ray Bradbury. Autgraphed play program of CSUF Theater Dept. production of the Dandelion Wine musical, 1971. Language of Material: English Access The collection is open for research. Preferred Citation Willis E. McNelly Science Fiction Collection: Ray Bradbury papers. California State University, Fullerton. University Archives and Special Collections Biography/Administrative History Ray Bradbury, in full Ray Douglas Bradbury, (born August 22, 1920, Waukegan, Illinois, U.S.—died June 5, 2012, Los Angeles, California), American author best known for his highly imaginative short stories and novels that blend a poetic style, nostalgia for childhood, social criticism, and an awareness of the hazards of runaway technology. Bradbury’s next novel, Fahrenheit 451 (1953), is regarded as his greatest work. -

OTHELLO by William Are, M Shakespeare Ew Y B Lo , R D O

SHADY SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY PROUDLY PRESENTS OTHELLO by William are, m Shakespeare ew y b lo , r d O , “ o f j e a l o u s ” y … July 25-August 29 at Sanborn Park WWW.SHADYSHAKES.ORG SHADY SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY PROUDLY PRESENTS Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen Adapted for the stage by Joseph Hanreddy and J.R. Sullivan “You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” August 1 - 31 at Sanborn Park Table of Contents Othello Cast ....................................................................................... 2 Othello Synopsis ................................................................................ 2 Othello Director’s Notes ................................................................... 3 Pride and Prejudice Cast ..................................................................... 4 Pride and Prejudice Synopsis .............................................................. 4 Pride and Prejudice Director’s Notes ................................................. 5 2014 Shady Shakespeare Crew ......................................................... 8 A Note from the Managing Director ............................................... 9 Artist Biographies ........................................................................... 10 2014 Sanborn Park Season Schedule ............................................. 13 2014 Season Sponsors .................................................................... 17 2014 Donors .................................................................................. -

Darkness Always Finds the Light

Mario Grill, BA Darkness Always Finds the Light: Emotion and Narrative in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Three Californias MASTER THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Programme: Master's programme English and American Studies Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Assoc. Prof. Dr. Alexa Weik von Mossner Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, April 2019 Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that • - the submitted academic thesis is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, • - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, • - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been in- cluded either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), • - to date, I have not submitted this thesis to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that • - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the pur- pose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Mario Grill e.h. Klagenfurt, 01.04.2019 (Signature)* (Place, date) For my sister Table of Contents AFFIDAVIT .......................................................................................................................................... -

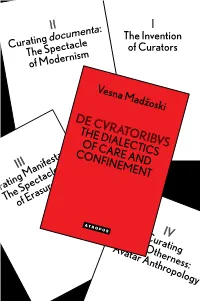

The Spectacle of Modernism IV Curating the Otherness

w DE $18.95 Philosophy / Media CVRATORIBVS II : I DE CVRATORIBVS documenta The Invention THE DIALECTICS OF CARE AND CONFINEMENT Curating of Curators The Spectacle How are we to analyze power relations in the current system of contemporary art, or the presumably non-existing censorship in of Modernism this free and democratic domain? The important event that struck Vesna Madzoski Vesna the art world in the last century was the appearance of a new agent on the art scene: that of a curator. The following analysis has Vesna Madzoski the ambition to strip curating down to its essence, by comparing three main domains in which we find this profession active: the ̌ ˇ Roman Empire, contemporary arts, and contemporary zoos. Two large-scale manifestations served as platforms for the DE CVRATORIBVS promotion and recognition of this profession, both with a clear THE DIALECTICS political mandate as well: documenta in Kassel, Germany, and the traveling Manifesta—European Biennial of Contemporary Art. OF CARE AND The third case-study, the Hollywood blockbuster film AVATAR, CONFINEMENT continues the discussion where the analysis of Manifesta brought us and, somehow, this perfect 3D cinematic image brings us back III to curators. What this historical overview made clear was, that what all those various agents have in common is a duty to pro- tect those considered to be in need of protection, which further Curating Manifesta: opened up the questions of who decided this, and where the The Spectacle threshold is when care becomes confinement. of Erasure Vesna Madzoskǐ is an independent writer and Think Media: EGS Media researcher based in Amsterdam. -

Unit 2: the Novel Fahrenheit 451: the Antihero

Name: _____________________________________ Block: _____ Date: ____________ Unit 2: The Novel Fahrenheit 451: The Antihero Directions: Pay careful attention to the video titled “An antihero of one’s own” by Tim Adams. Afterward, complete the following. 1. Our ancestors calmed our fears of powerlessness by giving us heroes to defeat the monsters that lived outside of ourselves. What does Adams say is the contemporary storytellers’ message? 2. Explain why antiheroes are more relatable than the heroes of ancient literature (such as Hercules, Beowulf, or King Arthur). 3. Name your favorite characters in literature. Are they antiheroes? Explain why or why not. 4. Antihero’s Story: For each stage of the anti-hero’s journey, cite examples from Fahrenheit 451 that demonstrate Guy Montag is an anti-hero. Initially Conforms to Society’s Rules Starts to Object, Finds Outsiders with Whom to Voice Questions Unwisely Shares Questions with an Authority Figure Openly Challenges Society 5. The video says that “Beowulf’s greatest enemy was mortality, Othello’s jealously, Hiccup self-doubt.” What do you believe is Guy Montag’s “greatest enemy?” Why? Ms. Muhlbaier Language Arts Name: _____________________________________ Block: _____ Date: ____________ Unit 2: The Novel Fahrenheit 451: Directions: Pay careful attention to the video titled “An antihero of one’s own” by Tim Adams. Afterward, complete the following. 1. Our ancestors calmed our fears of powerlessness by giving us heroes to defeat the monsters that lived outside of ourselves. What does Adams say is the contemporary storytellers' message? We must overcome the monsters that are not outside of us but within us. -

Montag's Transformation in the Dystopian World of Ray Bradbury's

The 5th TICC International Conference 2020 in Multidisciplinary Research Towards a Sustainable Society November 26th – 27th, 2020, Khon Kaen, Thailand MONTAG’S TRANSFORMATION IN THE DYSTOPIAN WORLD OF RAY BRADBURY’S FAHRENHEIT 451 Aphiradi Suphap1 Department of Western Languages, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences1 Thaksin University, Songkhla 90000, Thailand Email: [email protected] Abstract: This academic paper aims to explore Fahrenheit 451’s protagonist, Guy Montag’s transformation throughout the story to investigate how he has changed in the dystopian society where freedom is limited and information is distorted and if he succeeds in his transformation. The textual analysis is mainly employed in this article. His transformation is divided into four categories: transforming from indifferent to inquisitive; ignorant citizen to knowledgeable man; conforming to the society to rebelling against the society; and belonging to the society to the alienated person. Each state of transformation demonstrates his self-development. It enlightens him and gains him new knowledge that the state he lives in is full of false information and also discovers that he is not truly happy because he does not realize that he is forced to live the restricted life which he does not have any aims and does not genuinely have feelings for anything around him.After being through those transformations, he is, finally, successfulin seeing the world in the completely different perspectives and can start his new life outside the dystopian state. Keywords: Montag’s transformation, dystopia, Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury 1. Introduction Dystopia is “an apocalyptic version of future world with man taken over by the machine and technology playing havoc with human life. -

Ted Ankara College Foundation Private High School

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by TED Ankara College IB Thesis Barış Kandemir 001129-0064 TED ANKARA COLLEGE FOUNDATION PRIVATE HIGH SCHOOL ENGLISH B CATEGORY 3 EXTENDED ESSAY Candidate Name: Barış Kandemir Candidate Number: 001129-0064 Session: May 2014 Supervisor Name: Dilek Göktaş Word Count: 3722 Research Question: To what extent is the transformation of the protagonist in Fahrenheit 45(Guy Montag) similar or different to the protagonist in 1984 (Winston Smith) Barış Kandemir 001129-0064 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1) ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………..3 2) INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….4 3) ANALYSIS OF PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS………………………………8 A) GUY MONTAG………………………………………………………………8 B) WINSTON SMITH…………………………………………………………..11 4) CORRELATION BETWEEN THE TRANSFORMATION PROCESSES…15 5) CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………17 6) BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………18 2 Barış Kandemir 001129-0064 ABSTRACT This extended essay explores the extent of the similarities and differences between the transformations of the protagonists Guy Montag and Winston Smith. The research question is divided into the analysis of each protagonist with respect to their reality, which basically consists of oppressing, totalitarian, and manipulating governments, forcing their society to be emotionless and empty individuals. This investigation includes references to the novels, providing an in-depth analysis of each protagonist. These analyses consist of the adverse effects of the antagonist on the character and the role of supporting characters in the process. Apparently, combined with the nature of the protagonists, these effects comprise a great deal of complexity so this essay comprises of two sections where the characters are analyzed and a third part, in which the correlations of the events are evaluated. The information provided on this essay is based on the logical interpretation of knowledge into a reasoning system.