Overdone. Unfinished Business © 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

I L N O I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science University of Illinois Press 4 . $ 4 *. *"From the intriguing title to the final page, layers of cynical wit and care- ful choracter development occumulate achingfy in this beautfully rafted emotionally charged story" --Starred review, ScholLbary ornl *"Readers will take heart from the way Steve grows post his rebellion as they laugh at the plethora of comic situations and saply set up, welC executed punchllnes. "-Pointered review, Kirkus Reviews *"lt's Thomas's first novel and he has such an accurate voice that it screams read me now while I am hot and hot it is."-Starred review, VOYA 0689-80207.2 * $17.00 US/$23.O0 CAN (S&S BFYR) 0-689.80777-5 * $3.99 US/$4.99 CAN (Aladdin Ppoprboekst ALADDIN PAPERBACKS SIMON &f SCHUSTER BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS Imtprints of Simron &'P Schuster Children's Publishing· Division 1230 Avenue of the Americas * New Yorkr, NV 10020 THE B UL LE T IN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS September 1996 Vol. 50 No. 1 A LOOK INSIDE 3 THE BIG PICTURE American Fairy Tales: From Rip Van Winkle to the Rootabaga Stories comp. by Neil Philip; illustrated by Michael McCurdy 5 NEW BOOKS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE Reviewed titles include: 5 * The Story ofLittle Babaji by Helen Bannerman; illus. by Fred Marcellino 11 * The Abracadabra Kid by Sid Fleischman 16 * How to Make Holiday Pop-Ups by Joan Irvine; illus. -

The Art of Being Human First Edition

The Art of Being Human First Edition Michael Wesch Michael Wesch Copyright © 2018 Michael Wesch Cover Design by Ashley Flowers All rights reserved. ISBN: 1724963678 ISBN-13: 978-1724963673 ii The Art of Being Human TO BABY GEORGE For reminding me that falling and failing is fun and fascinating. iii Michael Wesch iv The Art of Being Human FIRST EDITION The following chapters were written to accompany the free and open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology course available at ANTH101.com. This book is designed as a loose framework for more and better chapters in future editions. If you would like to share some work that you think would be appropriate for the book, please contact the author at [email protected]. v Michael Wesch vi The Art of Being Human Praise from students: "Coming into this class I was not all that thrilled. Leaving this class, I almost cried because I would miss it so much. Never in my life have I taken a class that helps you grow as much as I did in this class." "I learned more about everything and myself than in all my other courses combined." "I was concerned this class would be off-putting but I needed the hours. It changed my views drastically and made me think from a different point of view." "It really had opened my eyes in seeing the world and the people around me differently." "I enjoyed participating in all 10 challenges; they were true challenges for me and I am so thankful to have gone out of my comfort zone, tried something new, and found others in this world." "This class really pushed me outside my comfort -

The Ultimate Playlist This List Comprises More Than 3000 Songs (Song Titles), Which Have Been Released Between 1931 and 2018, Ei

The Ultimate Playlist This list comprises more than 3000 songs (song titles), which have been released between 1931 and 2021, either as a single or as a track of an album. However, one has to keep in mind that more than 300000 songs have been listed in music charts worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century [web: http://tsort.info/music/charts.htm]. Therefore, the present selection of songs is obviously solely a small and subjective cross-section of the most successful songs in the history of modern music. Band / Musician Song Title Released A Flock of Seagulls I ran 1982 Wishing 1983 Aaliyah Are you that somebody 1998 Back and forth 1994 More than a woman 2001 One in a million 1996 Rock the boat 2001 Try again 2000 ABBA Chiquitita 1979 Dancing queen 1976 Does your mother know? 1979 Eagle 1978 Fernando 1976 Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! 1979 Honey, honey 1974 Knowing me knowing you 1977 Lay all your love on me 1980 Mamma mia 1975 Money, money, money 1976 People need love 1973 Ring ring 1973 S.O.S. 1975 Super trouper 1980 Take a chance on me 1977 Thank you for the music 1983 The winner takes it all 1980 Voulez-Vous 1979 Waterloo 1974 ABC The look of love 1980 AC/DC Baby please don’t go 1975 Back in black 1980 Down payment blues 1978 Hells bells 1980 Highway to hell 1979 It’s a long way to the top 1975 Jail break 1976 Let me put my love into you 1980 Let there be rock 1977 Live wire 1975 Love hungry man 1979 Night prowler 1979 Ride on 1976 Rock’n roll damnation 1978 Author: Thomas Jüstel -1- Rock’n roll train 2008 Rock or bust 2014 Sin city 1978 Soul stripper 1974 Squealer 1976 T.N.T. -

Kaleidoscope: a Multicultural Booklist for Grades K-8. NCTE Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 454 524 CS 217 590 AUTHOR Yokota, Junko, Ed. TITLE Kaleidoscope: A Multicultural Booklist for Grades K-8. Third Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN -,0- 8141- - 2540 -9 _ ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 244p.; For the previous edition, see ED 415 507. Produced with the Committee To Revise the Multicultural Booklist, NCTE. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 25409: $21.95 members; $28.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Ethnic Groups; *Fiction; Multicultural Education; *Nonfiction; *Picture Books; Poetry IDENTIFIERS Information Books; *Multicultural Literature; *Trade Books ABSTRACT The third edition of this annotated bibliography collection offers students, teachers, and librarians a helpful guide to the best multicultural literature (published between 1996 and 1998) for elementary and middle school readers. With approximately 600 annotations on topics and formats including picture story books, realistic fiction, history and historical fiction, ceremonies and celebrations, biographies and autobiographies, informational books, poetry, and folklore, this collection continues the "Kaleidoscope" tradition of focusing on books by and about people of color--specifically African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Native Americans. Each annotation provides bibliographic information and an informative summary that encapsulates not only content but also ethnic focus, nationality, or country of origin. A 16-page insert featuring some of the covers of annotated books showcases the talents of designers and illustrators. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Vfties at S&PMER GAMES

August 11, 1984 NEWSPAPER $3.0 XCLUSIVITY SMALL WCTOR F TV.JjAblOS IEGGAE GAINS WIThfliDrE^ Ai 1USIC MARKS omif sifi fl VfTIES AT S&PMER GAMES IIAA-SPONSORS WORKSHOPS • ?p, viopG Standar ds i Billy Squier REFERENCE TOOLS YEARS OF CHARTS FOR THE INDUSTRY AT YOUR FINGERTIPS TWO CUMULATIVE VOLUME 1 Two cumulative volumes, one de- voted to Cash Box popular music singles charts from 1950 through 1981. The other devoted to Cash Box country singles charts from 1958 through 1982. Both Volumes are valuable resources to anyone whose business is the music business. 15 % savings off list pric for CASH BOX subscribe! COUNTRY SINGLES CHARTS ONLY $37.50 SINGLES CHARTS ONLY $41.50 LIST PRICE $49.50 Both volumes contain the main ar- tist and song-title indexes includ- ing a week-by-week listing of song chart positions. Also compiled in these spectacular volumes are: the "Top Ten" records of each year, the most chart hits by an artist, the most #1 hits by an artist, the most weeks at #1 by an artist, the most weeks at #1 by a single record, the records with the longest chart run, and a chronological list of #1 records. THE CASH BOX SINGLES CHARTS SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 52 Liberty Street, Metuchen, N.J. 08840 1950-1981 Yes, please send me copy/copies of the CASHBOX SINGLES CHARTS, | and 1950-1981 at the special price of $41.50 i each + $2.00 postage and handling. L THE CASH BOX copy/copies of THE CASH BOX COUNTRY SINGLES priceof CHARTS, 1958-1982 at the special ,j COUNTRY $37.50 each + $2.00 postage and handling. -

Annual Report 08/09

2009 Informe anual Ayudamos a los pueblos indígenas a defender sus vidas, proteger sus tierras y decidir 2009 Este informe abarca su propio el trabajo de Survival durante un año, hasta futuro. principios de 2009 DONDEQUIERA QUE SE ENCUENTREN, LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS SE VEN PRIVADOS DE SU SUSTENTO Y MODO DE VIDA: LA MINERÍA, LA TALA O LOS s COLONOS LOS EXPULSAN DE SUS TIERRAS; SON DESPLAZADOS A LA FUERZA POR PRESAS, RANCHOS DE GANADO O RESERVAS DE CAZA. ESTOS ABUSOS A o MENUDO SE JUSTIFICAN ALEGANDO QUE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS SON, DE v ALGUNA FORMA, “PRIMITIVOS” O “ATRASADOS”. SURVIVAL TRABAJA POR UN i t MUNDO EN EL QUE LA DIVERSIDAD DE MODOS DE VIDA INDÍGENAS SEA COMPRENDIDA Y ACEPTADA, EN EL QUE NO SE TOLERE LA OPRESIÓN QUE e SUFREN Y SEAN LIBRES DE VIVIR EN SUS PROPIAS TIERRAS SEGÚN SUS MODOS j DE VIDA, EN PAZ, LIBERTAD Y SEGURIDAD. b nuestros objetivos o Survival trabaja para: • ayudar a los pueblos indígenas y tribales a ejercer su derecho a la supervivencia y a la autodeterminación ; • asegurar que los intereses de los pueblos indígenas y tribales estén adecuadamente representados en todas las decisiones que afecten a su futuro ; • asegurar a los pueblos indígenas y tribales la propiedad y la utilización de tierras y recursos adecuados, y obtener el reconocimiento de sus derechos sobre sus tierras tradicionales . nuestros métodos educación y sensibilización Survival produce publicaciones acerca de los pueblos indígenas dirigidas a centros educativos y al público general. Promovemos la idea de que los pueblos indígenas son tan “modernos” como el resto de nosotros, y que tienen derecho a vivir en su propia tierra, de acuerdo con sus propias creencias. -

The Art of Being Human: a Textbook for Cultural Anthropology

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2018 The Art of Being Human: A Textbook for Cultural Anthropology Michael Wesch Kansas State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Multicultural Psychology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wesch, Michael, "The Art of Being Human: A Textbook for Cultural Anthropology" (2018). NPP eBooks. 20. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. student submissions at anth101.com Anthropology is the study of all humans in all times in all places. But it is so much more than that. “Anthropology“ requires strength, valor, and courage,” Nancy Scheper-Hughes noted. “Pierre Bourdieu called anthropology a combat sport, an extreme sport as well as a tough and rigorous discipline. … It teaches students not to be afraid of getting one’s hands dirty, to get down in the dirt, and to commit yourself, body and mind. Susan Sontag called anthropology a “heroic” profession.” WhatW is the payoff for this heroic journey? You will find ideas that can carry you across rivers of doubt and over mountains of fear to find the the light and life of places forgotten. Real anthropology cannot be contained in a book. -

Scholz.No › Wordpress › Wp-Content › Uploads › 2010

GRATIS-NYTT NUMMER! sommeren 2009 STOR FESTIVAL- QUIZ VINN FESTIVALPASS PRETENDERS TIL NORWEGIAN WOOD SOMMERENS FERGIE BESTE FILMER TIL QUART'N YOGA I NORDMARKA Hvis det finnes en sko som får hard asfalt til å føles som myk mose, som trener kjernemuskulaturen din mens du går og står, kan lindre smerter i rygg og knær, avlaste leddene dine og gi deg bedre kroppsholdning - hvorfor ikke prøve den? Nytt design, samme effekt! www.masainorge.no www.masainorge.no 2 tter en så fantastisk pinse, vil vi bare ha mer. Mer sol, flere lettkledde mennesker, mer god mat på grillen, mer godt i glasset- rett og slett mer! I denne utgaven av Cafemagasinet får du nettopp det. Her er . litt av hvert du kan glede deg over. Først og fremst festivaler. frognerbadet oslo For hva er vel sommeren uten festivaler? Vi snakker Norwegian . 9 11.-14. juni 200 EWood, Hove, Øya og Quarten. På Wood møter du blant andre Duffy, Neil Young, Big Bang og ikke minst The Pretenders og Chrissie Hynde. Her kan festivaldeltakerne til og med benytte seg av svømmebassengene hvis det skulle bli for hett. Hove Torsdag 11. juni Lørdag 13. juni frister med telt og strand i tillegg til god musikk fra artister som The Killers og Franz Ferdinand. De starter opp en dag tidligere enn planlagt, UTSOLGT NeilYoung BigBang så merk at campen åpner allerede fredag & his 19.juni. Øya har fått tak i Rise Against The Pretenders som er et melodisk hardpunkrock band Electric fra Chicago. Bandet startet opp i 1999, Todd Rundgren og har så langt sluppet ut fem plater. -

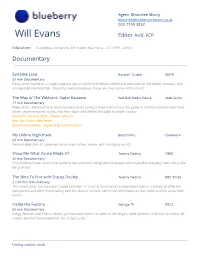

Will Evans Editor A Vid, FCP

Agent: Bhavinee Mistry [email protected] 020 7199 3852 Will Evans Editor Avid, FCP Education St Andrews University, Art History Ma (Hons) - 2:1 (1999 - 2004 ) Documentary Extreme Love Barcroft Studios WeTV 60 min Documentary Docu-series based on a hugely popular digital series that follows weird and wild tales of incredible, unusual, and unexpected relationships. Shocking and outrageous, these are love stories with a twist! The Way of The Wildcard: Sadat Kawawa Red Bull Media House Web Series 17 min Documentary Web series - Observational documentary series telling stories from across the globe of unlikely athletes who have taken unconventional routes into their sport and defied the odds to reach success. Realscreen Awards 2018 – Double Winners Best Non-Fiction Web Series Award of Excellence – Digital & Branded Content My Online Nightmare Blast! Films Channel 4 60 min Documentary Remarkable tales of scammers who lured victims online, with terrifying results. Show Me What You’re Made Of Twenty Twenty CBBC 30 min Documentary Five children travel across the world to live and work alongside the people who make the everyday items they take for granted. The Nine To Five with Stacey Dooley Twenty Twenty BBC Three 2 x 30 min Documentary This series gives five teenagers (aged between 16 and 18) the chance to experience jobs in a variety of different workplaces and offer those taking part the chance to learn some real life lessons as they work and live away from home. Inside the Factory Voltage TV BBC2 60 min Documentary Gregg Wallace and Cherry Healey get exclusive access to some of the largest food factories in Britain to reveal the secrets behind food production on an epic scale. -

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988

Ladyslipper Catalog • and Resource Guide • 1988 Records • Tapes Compact Discs Videos V\M Women Mf\A About Ladyslipper Ladyslipper is a North Carolina non-profit, tax- 1982 brought the first release on the Ladys exempt organization which has been involved lipper label Marie Rhines/Tartans & Sagebrush, in many facets of women's music since 1976. originally released on the Biscuit City label. In Our basic purpose has consistently been to 1984 we produced our first album, Kay Gard heighten public awareness of the achievements ner/A Rainbow Path. In 1985 we released the of women artists and musicians and to expand first new wave/techno-pop women's music al the scope and availability of musical and liter bum, Sue Fink/Big Promise; put the new age ary recordings by women. album Beth York/Transformations onto vinyl; and released another new age instrumental al One of the unique aspects of our work has bum, Debbie Fier/Firelight. Our purpose as a been the annual publication of the world's most label is to further new musical and artistic direc comprehensive Catalog and Resource Guide of tions for women artists. Records and Tapes by Women—the one you now hold in your hands. This grows yearly as Our name comes from an exquisite flower the number of recordings by women continues which is one of the few wild orchids native to to develop in geometric proportions. This anno North America and is currently an endangered tated catalog has given thousands of people in species. formation about and access to recordings by an expansive variety of female musicians, writers, Donations are tax-deductible, and we do need comics, and composers. -

Untitled Meditation No

TABLE OF CONTENTS Ordering Information 2 Women's Spirituality * New Age 36 Ladyslipper On-Line! http://ww.ladyslipper.org 3 Women's Music * Feminist * Lesbian 45 Order Blank 4 Alternative 53 Gift Orders * Gift Certificates 5 Rock * Pop 56 Ladyslipper Listen Line * Buy A Brick 6 Folk * Singer-Songwriter 58 Ladyslipper Mailing List * E-Mail List 8 Country 63 How To Celebrate Our 20th Anniversary? 9 Jazz 64 Ladyslipper's Top 100 10 Blues 65 Musical Month Club * Donor Discount Club 11 Gospel 66 Free Gifts * Cassette Madness Sale 12 R&B * Rap 66 Holiday 13 Dance 67 Cards * Posters * Grab-Bags 16 Cabaret 68 Calendars 17 Soundtracks 69 Classical 18 Choral 70 World 20 "Mehn's Music" 72 Celtic * British Isles 21 Comedy 76 European 26 Spoken 77 Latin American 27 Babyslipper Catalog 78 Asian * Pacific 29 Videos 79 Arabic * Middle Eastern 29 T-Shirts * Music Screeners 83 Jewish 30 Songbooks 83 African 31 Books 84 African Heritage 31 Readers' Comments 85 Native American 33 Ladyslipper Anniversary Concerts 86 Drumming * Percussion 34 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper PO Box 3124, Durham NC 27715 USA PHONE ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fn 9-9. Sat 11-5 Eastern Time FAX ORDERS: 919-383-3525 INFORMATION: 919-383-8773 ORDERING INFO E-MAIL: orders®! adyshpperorg WEB SITE: http//w PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available.