A Programmer's Persp. 2Nd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSE 220: Systems Programming

Memory Allocation CSE 220: Systems Programming Ethan Blanton Department of Computer Science and Engineering University at Buffalo Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Allocating Memory We have seen how to use pointers to address: An existing variable An array element from a string or array constant This lecture will discuss requesting memory from the system. © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 2 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Memory Lifetime All variables we have seen so far have well-defined lifetime: They persist for the entire life of the program They persist for the duration of a single function call Sometimes we need programmer-controlled lifetime. © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 3 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Examples int global ; /* Lifetime of program */ void foo () { int x; /* Lifetime of foo () */ } Here, global is statically allocated: It is allocated by the compiler It is created when the program starts It disappears when the program exits © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 4 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary Examples int global ; /* Lifetime of program */ void foo () { int x; /* Lifetime of foo () */ } Whereas x is automatically allocated: It is allocated by the compiler It is created when foo() is called ¶ It disappears when foo() returns © 2021 Ethan Blanton / CSE 220: Systems Programming 5 Introduction The Heap Void Pointers The Standard Allocator Allocation Errors Summary The Heap The heap represents memory that is: allocated and released at run time managed explicitly by the programmer only obtainable by address Heap memory is just a range of bytes to C. -

Memory Allocation Pushq %Rbp Java Vs

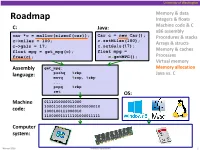

University of Washington Memory & data Roadmap Integers & floats C: Java: Machine code & C x86 assembly car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Procedures & stacks c.setMiles(100); c->miles = 100; Arrays & structs c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Memory & caches free(c); c.getMPG(); Processes Virtual memory Assembly get_mpg: Memory allocation pushq %rbp Java vs. C language: movq %rsp, %rbp ... popq %rbp ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 1 University of Washington Memory Allocation Topics Dynamic memory allocation . Size/number/lifetime of data structures may only be known at run time . Need to allocate space on the heap . Need to de-allocate (free) unused memory so it can be re-allocated Explicit Allocation Implementation . Implicit free lists . Explicit free lists – subject of next programming assignment . Segregated free lists Implicit Deallocation: Garbage collection Common memory-related bugs in C programs Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 2 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Allocation Programmers use dynamic memory allocators (such as malloc) to acquire virtual memory at run time . For data structures whose size (or lifetime) is known only at runtime Dynamic memory allocators manage an area of a process’ virtual memory known as the heap User stack Top of heap (brk ptr) Heap (via malloc) Uninitialized data (.bss) Initialized data (.data) Program text (.text) 0 Winter 2016 Memory Allocation 3 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Allocation Allocator organizes the heap as a collection of variable-sized blocks, which are either allocated or free . Allocator requests pages in heap region; virtual memory hardware and OS kernel allocate these pages to the process . -

Unleashing the Power of Allocator-Aware Software

P2126R0 2020-03-02 Pablo Halpern (on behalf of Bloomberg): [email protected] John Lakos: [email protected] Unleashing the Power of Allocator-Aware Software Infrastructure NOTE: This white paper (i.e., this is not a proposal) is intended to motivate continued investment in developing and maturing better memory allocators in the C++ Standard as well as to counter misinformation about allocators, their costs and benefits, and whether they should have a continuing role in the C++ library and language. Abstract Local (arena) memory allocators have been demonstrated to be effective at improving runtime performance both empirically in repeated controlled experiments and anecdotally in a variety of real-world applications. The initial development and subsequent maintenance effort of implementing bespoke data structures using custom memory allocation, however, are typically substantial and often untenable, especially in the limited timeframes that urgent business needs impose. To address such recurring performance needs effectively across the enterprise, Bloomberg has adopted a consistent, ubiquitous allocator-aware software infrastructure (AASI) based on the PMR-style1 plug-in memory allocator protocol pioneered at Bloomberg and adopted into the C++17 Standard Library. In this paper, we highlight the essential mechanics and subtle nuances of programing on top of Bloomberg’s AASI platform. In addition to delineating how to obtain performance gains safely at minimal development cost, we explore many of the inherent collateral benefits — such as object placement, metrics gathering, testing, debugging, and so on — that an AASI naturally affords. After reading this paper and surveying the available concrete allocators (provided in Appendix A), a competent C++ developer should be adequately equipped to extract substantial performance and other collateral benefits immediately using our AASI. -

P1083r2 | Move Resource Adaptor from Library TS to the C++ WP

P1083r2 | Move resource_adaptor from Library TS to the C++ WP Pablo Halpern [email protected] 2018-11-13 | Target audience: LWG 1 Abstract When the polymorphic allocator infrastructure was moved from the Library Fundamentals TS to the C++17 working draft, pmr::resource_adaptor was left behind. The decision not to move pmr::resource_adaptor was deliberately conservative, but the absence of resource_adaptor in the standard is a hole that must be plugged for a smooth transition to the ubiquitous use of polymorphic_allocator, as proposed in P0339 and P0987. This paper proposes that pmr::resource_adaptor be moved from the LFTS and added to the C++20 working draft. 2 History 2.1 Changes from R1 to R2 (in San Diego) • Paper was forwarded from LEWG to LWG on Tuesday, 2018-10-06 • Copied the formal wording from the LFTS directly into this paper • Minor wording changes as per initial LWG review • Rebased to the October 2018 draft of the C++ WP 2.2 Changes from R0 to R1 (pre-San Diego) • Added a note for LWG to consider clarifying the alignment requirements for resource_adaptor<A>::do_allocate(). • Changed rebind type from char to byte. • Rebased to July 2018 draft of the C++ WP. 3 Motivation It is expected that more and more classes, especially those that would not otherwise be templates, will use pmr::polymorphic_allocator<byte> to allocate memory. In order to pass an allocator to one of these classes, the allocator must either already be a polymorphic allocator, or must be adapted from a non-polymorphic allocator. The process of adaptation is facilitated by pmr::resource_adaptor, which is a simple class template, has been in the LFTS for a long time, and has been fully implemented. -

The Slab Allocator: an Object-Caching Kernel Memory Allocator

The Slab Allocator: An Object-Caching Kernel Memory Allocator Jeff Bonwick Sun Microsystems Abstract generally superior in both space and time. Finally, Section 6 describes the allocator’s debugging This paper presents a comprehensive design over- features, which can detect a wide variety of prob- view of the SunOS 5.4 kernel memory allocator. lems throughout the system. This allocator is based on a set of object-caching primitives that reduce the cost of allocating complex objects by retaining their state between uses. These 2. Object Caching same primitives prove equally effective for manag- Object caching is a technique for dealing with ing stateless memory (e.g. data pages and temporary objects that are frequently allocated and freed. The buffers) because they are space-efficient and fast. idea is to preserve the invariant portion of an The allocator’s object caches respond dynamically object’s initial state — its constructed state — to global memory pressure, and employ an object- between uses, so it does not have to be destroyed coloring scheme that improves the system’s overall and recreated every time the object is used. For cache utilization and bus balance. The allocator example, an object containing a mutex only needs also has several statistical and debugging features to have mutex_init() applied once — the first that can detect a wide range of problems throughout time the object is allocated. The object can then be the system. freed and reallocated many times without incurring the expense of mutex_destroy() and 1. Introduction mutex_init() each time. An object’s embedded locks, condition variables, reference counts, lists of The allocation and freeing of objects are among the other objects, and read-only data all generally qual- most common operations in the kernel. -

Fast Efficient Fixed-Size Memory Pool: No Loops and No Overhead

COMPUTATION TOOLS 2012 : The Third International Conference on Computational Logics, Algebras, Programming, Tools, and Benchmarking Fast Efficient Fixed-Size Memory Pool No Loops and No Overhead Ben Kenwright School of Computer Science Newcastle University Newcastle, United Kingdom, [email protected] Abstract--In this paper, we examine a ready-to-use, robust, it can be used in conjunction with an existing system to and computationally fast fixed-size memory pool manager provide a hybrid solution with minimum difficulty. On with no-loops and no-memory overhead that is highly suited the other hand, multiple instances of numerous fixed-sized towards time-critical systems such as games. The algorithm pools can be used to produce a general overall flexible achieves this by exploiting the unused memory slots for general solution to work in place of the current system bookkeeping in combination with a trouble-free indexing memory manager. scheme. We explain how it works in amalgamation with Alternatively, in some time critical systems such as straightforward step-by-step examples. Furthermore, we games; system allocations are reduced to a bare minimum compare just how much faster the memory pool manager is to make the process run as fast as possible. However, for when compared with a system allocator (e.g., malloc) over a a dynamically changing system, it is necessary to allocate range of allocations and sizes. memory for changing resources, e.g., data assets Keywords-memory pools; real-time; memory allocation; (graphical images, sound files, scripts) which are loaded memory manager; memory de-allocation; dynamic memory dynamically at runtime. -

Effective STL

Effective STL Author: Scott Meyers E-version is made by: Strangecat@epubcn Thanks is given to j1foo@epubcn, who has helped to revise this e-book. Content Containers........................................................................................1 Item 1. Choose your containers with care........................................................... 1 Item 2. Beware the illusion of container-independent code................................ 4 Item 3. Make copying cheap and correct for objects in containers..................... 9 Item 4. Call empty instead of checking size() against zero. ............................. 11 Item 5. Prefer range member functions to their single-element counterparts... 12 Item 6. Be alert for C++'s most vexing parse................................................... 20 Item 7. When using containers of newed pointers, remember to delete the pointers before the container is destroyed. ........................................................... 22 Item 8. Never create containers of auto_ptrs. ................................................... 27 Item 9. Choose carefully among erasing options.............................................. 29 Item 10. Be aware of allocator conventions and restrictions. ......................... 34 Item 11. Understand the legitimate uses of custom allocators........................ 40 Item 12. Have realistic expectations about the thread safety of STL containers. 43 vector and string............................................................................48 Item 13. Prefer vector -

Memory Allocation

University of Washington Today ¢ Dynamic memory allocaon § Size of data structures may only be known at run 6me § Need to allocate space on the heap § Need to de-allocate (free) unused memory so it can be re-allocated ¢ Implementaon § Implicit free lists § Explicit free lists – subject of next programming assignment § Segregated free lists ¢ Garbage collecon ¢ Common memory-related bugs in C programs Autumn 2012 Memory Alloca7on 1 University of Washington Process Memory Image memory protected kernel virtual memory from user code stack %esp What is the heap for? How do we use it? run-me heap uninialized data (.bss) inialized data (.data) program text (.text) 0 Autumn 2012 Memory Alloca7on 2 University of Washington Process Memory Image memory protected kernel virtual memory from user code stack %esp Allocators request addional heap memory from the kernel using the sbrk() funcon: the “brk” ptr error = sbrk(amt_more) run-me heap (via malloc) uninialized data (.bss) inialized data (.data) program text (.text) 0 Autumn 2012 Memory Alloca7on 3 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Alloca7on ¢ Memory allocator? Applica7on § VM hardware and kernel allocate pages § Applicaon objects are typically smaller Dynamic Memory Allocator § Allocator manages objects within pages Heap Memory ¢ How should the applica4on code allocate memory? Autumn 2012 Memory Alloca7on 4 University of Washington Dynamic Memory Alloca7on ¢ Memory allocator? Applica7on § VM hardware and kernel allocate pages § Applicaon objects are typically smaller Dynamic Memory Allocator -

Composing High-Performance Memory Allocators

Composing High-Performance Memory Allocators Emery D. Berger Benjamin G. Zorn Kathryn S. McKinley Dept. of Computer Sciences Microsoft Research Dept. of Computer Science The University of Texas at Austin One Microsoft Way University of Massachusetts Austin, TX 78712 Redmond, WA 98052 Amherst, MA 01003 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT server [1] and Microsoft’s SQL Server [10], use one or more cus- Current general-purpose memory allocators do not provide suffi- tom allocators. cient speed or flexibility for modern high-performance applications. Custom allocators can take advantage of certain allocation pat- Highly-tuned general purpose allocators have per-operation costs terns with extremely low-cost operations. For example, a program- around one hundred cycles, while the cost of an operation in a cus- mer can use a region allocator to allocate a number of small objects tom memory allocator can be just a handful of cycles. To achieve with a known lifetime and then free them all at once [11, 19, 23]. high performance, programmers often write custom memory allo- This customized allocator returns individual objects from a range cators from scratch – a difficult and error-prone process. of memory (i.e., a region), and then deallocates the entire region. In this paper, we present a flexible and efficient infrastructure The per-operation cost for a region-based allocator is only a hand- for building memory allocators that is based on C++ templates and ful of cycles (advancing a pointer and bounds-checking), whereas inheritance. This novel approach allows programmers to build cus- for highly-tuned, general-purpose allocators, the per-operation cost tom and general-purpose allocators as “heap layers” that can be is around one hundred cycles [11]. -

A Progressive Register Allocator for Irregular Architectures

A Progressive Register Allocator for Irregular Architectures David Koes and Seth Copen Goldstein Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University {dkoes,seth}@cs.cmu.edu Abstract example, graph coloring). Ideally, the reduction produces a problem that is proper, expressive, and progressive. We Register allocation is one of the most important op- define these properties as follows-aregister allocator is: timizations a compiler performs. Conventional graph- coloring based register allocators are fast and do well on • Proper if an optimal solution to the reduced problem regular, RISC-like, architectures, but perform poorly on ir- is also an optimal register allocation. Since optimal regular, CISC-like, architectures with few registers and non- register allocation is NP-complete [25, 20], it is un- orthogonal instruction sets. At the other extreme, optimal likely that efficient algorithms will exist for solving register allocators based on integer linear programming are the reduced problem. The optimality criterion can be capable of fully modeling and exploiting the peculiarities of any metric that can be statically evaluated at compile irregular architectures but do not scale well. We introduce time such as code size or compiler-estimated execution the idea of a progressive allocator. A progressive allocator time. finds an initial allocation of quality comparable to a con- • ventional allocator, but as more time is allowed for compu- Expressive if the reduced problem is capable of ex- tation the quality of the allocation approaches optimal. This plicitly representing architectural irregularities and paper presents a progressive register allocator which uses a costs. For example, such a register allocator would be multi-commodity network flow model to elegantly represent able to utilize information about the cost of assigning the intricacies of irregular architectures. -

Implementing a New Register Allocator for the Server Compiler in the Java Hotspot Virtual Machine

UPTEC IT 15011 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2015 Implementing a New Register Allocator for the Server Compiler in the Java HotSpot Virtual Machine Niclas Adlertz Institutionen för informationsteknologi Department of Information Technology Abstract Implementing a New Register Allocator for the Server Compiler in the Java HotSpot Virtual Machine Niclas Adlertz Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten The Java HotSpot Virtual Machine currently uses two Just In Time compilers to increase the performance of Java code in execution. The client and server compilers, Besöksadress: as they are named, serve slightly different purposes. The client compiler produces Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 code fast, while the server compiler produces code of greater quality. Both are Hus 4, Plan 0 important, because in a runtime environment there is a tradeoff between compiling and executing code. However, maintaining two separate compilers leads to increased Postadress: maintenance and code duplication. Box 536 751 21 Uppsala An important part of the compiler is the register allocator which has high impact on Telefon: the quality of the produced code. The register allocator decides which local variables 018 – 471 30 03 and temporary values that should reside in physical registers during execution. This Telefax: thesis presents the implementation of a second register allocator in the server 018 – 471 30 00 compiler. The purpose is to make the server compiler more flexible, allowing it to produce code fast or produce code of greater quality. This would be a major step Hemsida: towards making the client compiler redundant. http://www.teknat.uu.se/student The new register allocator is based on an algorithm called the linear scan algorithm, which is also used in the client compiler. -

GUARDER: a Tunable Secure Allocator

GUARDER: A Tunable Secure Allocator Sam Silvestro, Hongyu Liu, and Tianyi Liu, University of Texas at San Antonio; Zhiqiang Lin, Ohio State University; Tongping Liu, University of Texas at San Antonio https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity18/presentation/silvestro This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium. August 15–17, 2018 • Baltimore, MD, USA ISBN 978-1-939133-04-5 Open access to the Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX. GUARDER: A Tunable Secure Allocator Sam Silvestro∗ Hongyu Liu∗ Tianyi Liu∗ Zhiqiang Lin† Tongping Liu∗ ∗University of Texas at San Antonio †The Ohio State University Abstract Vulnerability Occurrences (#) Heap Overflow 673 Due to the on-going threats posed by heap vulnerabili- Heap Over-read 125 Invalid-free 35 ties, we design a novel secure allocator — GUARDER— Double-free 33 to defeat these vulnerabilities. GUARDER is different Use-after-free 264 from existing secure allocators in the following aspects. Existing allocators either have low/zero randomization Table 1: Heap vulnerabilities reported in 2017. entropy, or cannot provide stable security guarantees, where their entropies vary by object size classes, exe- dows versions [12]. Heap vulnerabilities still widely ex- cution phases, inputs, or applications. GUARDER en- ist in different types of in-production software, where Ta- sures the desired randomization entropy, and provides an ble 1 shows those reported in the past year at NVD [29]. unprecedented level of security guarantee by combining Secure memory allocators typically serve as the first all security features of existing allocators, with overhead line of defense against heap vulnerabilities.