Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (Pahs) | ATSDR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capture and Reuse of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) for a Plastics Circular Economy: a Review

processes Review Capture and Reuse of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) for a Plastics Circular Economy: A Review Laura Pires da Mata Costa 1 ,Débora Micheline Vaz de Miranda 1, Ana Carolina Couto de Oliveira 2, Luiz Falcon 3, Marina Stella Silva Pimenta 3, Ivan Guilherme Bessa 3,Sílvio Juarez Wouters 3,Márcio Henrique S. Andrade 3 and José Carlos Pinto 1,* 1 Programa de Engenharia Química/COPPE, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Cidade Universitária, CP 68502, Rio de Janeiro 21941-972, Brazil; [email protected] (L.P.d.M.C.); [email protected] (D.M.V.d.M.) 2 Escola de Química, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Cidade Universitária, CP 68525, Rio de Janeiro 21941-598, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Braskem S.A., Rua Marumbi, 1400, Campos Elíseos, Duque de Caxias 25221-000, Brazil; [email protected] (L.F.); [email protected] (M.S.S.P.); [email protected] (I.G.B.); [email protected] (S.J.W.); [email protected] (M.H.S.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-21-3938-8709 Abstract: Plastic production has been increasing at enormous rates. Particularly, the socioenvi- ronmental problems resulting from the linear economy model have been widely discussed, espe- cially regarding plastic pieces intended for single use and disposed improperly in the environment. Nonetheless, greenhouse gas emissions caused by inappropriate disposal or recycling and by the Citation: Pires da Mata Costa, L.; many production stages have not been discussed thoroughly. Regarding the manufacturing pro- Micheline Vaz de Miranda, D.; Couto cesses, carbon dioxide is produced mainly through heating of process streams and intrinsic chemical de Oliveira, A.C.; Falcon, L.; Stella transformations, explaining why first-generation petrochemical industries are among the top five Silva Pimenta, M.; Guilherme Bessa, most greenhouse gas (GHG)-polluting businesses. -

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002 Members Present: Dr Stephen Heller, Prof Herbert Kaesz, Prof Dr Alexander Lawson, Prof G. Jeffrey Leigh, Dr Alan McNaught (President), Dr. Gerard Moss, Prof Bruce Novak, Dr Warren Powell (Secretary), Dr William Town, Dr Antony Williams Members Absent: Dr. Michael Dennis, Prof Michael Hess National representatives Present: Prof Roberto de Barros Faria (Brazil) The second meeting of the Division Committee of the IUPAC Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation held in the Great Republic Room of the Westin Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, USA was convened by President Alan McNaught at 9:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 18, 2002. 1.0 President McNaught welcomed the members to this meeting in Boston and offered a special welcome to the National Representative from Brazil, Prof Roberto de Barros Faria. He also noted that Dr Michael Dennis and Prof Michael Hess were unable to be with us. Each of the attendees introduced himself and provided a brief bit of background information. Housekeeping details regarding breaks and lunch were announced and an invitation to a reception from the U. S. National Committee for IUPAC on Tuesday, August 20 was noted. 2.0 The agenda as circulated was approved with the addition of a report from Dr Moss on the activity on his website. 3.0 The minutes of the Division Committee Meeting in Cambridge, UK, January 25, 2002 as posted on the Webboard (http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.rtf and http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.pdf) were approved with the following corrections: 3.1 The name Dr Gerard Moss should be added to the members present listing. -

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Migration from Creosote-Treated Railway Ties Into Ballast and Adjacent Wetlands

United States In cooperation Department of with the Agriculture Polycyclic Aromatic United States Forest Service Department of Transportation Hydrocarbon Migration Forest Products Federal Laboratory Highway Administration From Creosote-Treated Research Paper FPL−RP−617 Railway Ties Into Ballast and Adjacent Wetlands Kenneth M. Brooks Abstract from the weathered ties at this time. No significant PAH loss was observed from ties during the second summer. A Occasionally, creosote-treated railroad ties need to be small portion of PAH appeared to move vertically down into replaced, sometimes in sensitive environments such as the ballast to approximately 60 cm. Small amounts of PAH wetlands. To help determine if this is detrimental to the may have migrated from the ballast into adjacent wetlands surrounding environment, more information is needed on during the second summer, but these amounts were not the extent and pattern of creosote, or more specifically poly- statistically significant. These results suggest that it is rea- cyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH), migration from railroad sonable to expect a detectable migration of creosote-derived ties and what effects this would have on the surrounding PAH from newly treated railway ties into supporting ballast environment. This study is a report on PAH level testing during their first exposure to hot summer weather. The PAH done in a simulated wetland mesocosm. Both newly treated rapidly disappeared from the ballast during the fall and and weathered creosote-treated railroad ties were placed in winter following this initial loss. Then statistically insignifi- the simulated wetland. As a control, untreated ties were also cant vertical and horizontal migration of these PAH suggests placed in the mesocosm. -

Electronic Cigarettes (E-Cigarettes)

Electronic Cigarettes (e-cigarettes) Electronic cigarettes (also called -e cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems) are battery-operated devices designed to deliver nicotine with flavorings and other chemicals to users in vapor instead of smoke. They can be manufactured to resemble traditional tobacco cigarettes, cigars or pipes, or even everyday items like pens or USB memory sticks; newer devices, such as those with fillable tanks, may look different. More than 250 different e-cigarette brands are currently on the market. While e-cigarettes are often promoted as safer alternatives to traditional cigarettes, which deliver nicotine by burning tobacco, little is actually known yet about the health risks of using these devices. How do e-cigarettes work? Electronic cigarettes are Most e-cigarettes consist of three different components, including: battery-operated devices a cartridge, which holds a liquid solution containing varying amounts of designed to deliver nicotine nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals with flavorings and other a heating device (vaporizer) chemicals to users in vapor a power source (usually a battery) instead of smoke. In many e-cigarettes, puffing activates the battery-powered heating device, Although they do not which vaporizes the liquid in the cartridge. The resulting aerosol or vapor is produce tobacco smoke, then inhaled (called "vaping"). e-cigarettes still contain nicotine and other Are e-cigarettes safer than conventional cigarettes? potentially harmful Unfortunately, this question is difficult to answer because insufficient information chemicals. is available on these new products. Early evidence suggest that Cigarette smoking remains the leading preventable cause of sickness and e-cigarette use may serve as mortality, responsible for over 400,000 deaths in the United States each year. -

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure Index

NIST Special Publication 922 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure Index Lane C. Sander and Stephen A. Wise Chemical Science and Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899-0001 December 1997 revised August 2020 U.S. Department of Commerce William M. Daley, Secretary Technology Administration Gary R. Bachula, Acting Under Secretary for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Raymond G. Kammer, Director Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure Index Lane C. Sander and Stephen A. Wise Chemical Science and Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 This tabulation is presented as an aid in the identification of the chemical structures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The Structure Index consists of two parts: (1) a cross index of named PAHs listed in alphabetical order, and (2) chemical structures including ring numbering, name(s), Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) Registry numbers, chemical formulas, molecular weights, and length-to-breadth ratios (L/B) and shape descriptors of PAHs listed in order of increasing molecular weight. Where possible, synonyms (including those employing alternate and/or obsolete naming conventions) have been included. Synonyms used in the Structure Index were compiled from a variety of sources including “Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons Nomenclature Guide,” by Loening, et al. [1], “Analytical Chemistry of Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds,” by Lee et al. [2], “Calculated Molecular Properties of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons,” by Hites and Simonsick [3], “Handbook of Polycyclic Hydrocarbons,” by J. R. Dias [4], “The Ring Index,” by Patterson and Capell [5], “CAS 12th Collective Index,” [6] and “Aldrich Structure Index” [7]. In this publication the IUPAC preferred name is shown in large or bold type. -

Characterization of Activated Carbon Produced from Coffee Residues by Chemical and Physical Activation

Activated carbon Characterization of activated carbon produced from coffee residues by chemical and physical activation JAVIER SÁNCHEZ AZNAR KTH Chemical Science and Engineering Master Thesis in Chemical Engineering Stockholm, Sweden, March 2011 - 1 - Activated carbon List of figures PART 1 Fig 1.1 Representation of the structure of activated carbons (H. Fritzst Oeckli 1990)(47).7 Fig 1.2 The six isotherm types according to IUPAC……………………………………...8 Fig 1.3 Representation of the three types of pores according to the IUPAC………….....14 Fig 1.4 Texture of dust activated carbon………………………………………………...19 Fig 1.5 Texture of granular activated carbon…………………………………………….19 Fig 1.6 Structure of a coffee bean………………………………………………………..23 PART 2 Fig 2.1 Furnace employed for carbonization…………………………………………….31 Fig 2.2 Magnetic stirrer during HCL washing…………………………………………..32 Fig 2.3 Steam activation system…………………………………………………………33 Fig 2.4 ASAP instrument………………………………………………………………...34 PART 3 Fig 3.1 Results of yields for 30%, 40% and 50% samples by chemical activation at different temperatures…………………………………………………………………....38 Fig 3. 2. Results of yields for samples activated by steam at different temperatures……39 Fig 3.3 Results of volatile and ash content by chemical and steam activation…………..40 Fig 3.4 Results of BET surface area (m 2/g)……………………………………………...42 Fig 3. 5 Isotherm of the sample CA_3_500……………………………………………...44 Fig 3.6 Isotherm of the sample CA_3_600……………………………….……………...44 Fig 3.7 Isotherm of the sample CA_3_700……………………………….……………...44 Fig 3.8 Isotherm of the -

Hardwood-Distillation Industry

HARDWOOD-DISTILLATION INDUSTRY No. 738 Revised February 1956 41. /0111111 110 111111111111111111 t I 1, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST PRODUCTS LABORATORY FOREST SERVICE MADISON 5, WISCONSIN. In Cooperation with the University of Wisconsin 1 HARDWOOD-DISTILLATION INDUSTRY— By EDWARD BEGLINGER, Chemical Engineer 2 Forest Products Laboratory, — Forest Service U. S. Department of Agriculture The major portion of wood distillation products in the United States is obtained from forest and mill residues, chiefly beech, birch, maple, oak, and ash. Marketing of the natural byproducts recovered has been concerned traditionally with outlets for acetic acid, methanol, and charcoal. Large and lower cost production of acetic acid and methanol from other sources has severely curtailed markets formerly available to the distillation in- dustry, and has in turn created operational conditions generally unfavor- able to many of the smaller and more marginal plants. Increased demand for charcoal, which is recovered in the largest amount as a plant product, now provides a compensating factor for more favorable plant operation. The present hardwood-distillation industry includes six byproduct-recovery plants. With the exception of one smaller plant manufacturing primarily a specialty product, all have modern facilities for direct byproduct re- covery. Changing economic conditions during the past 25 years, including such factors as progressively increasing raw material, equipment, and labor costs, and lack of adequate markets for methanol and acetic acid, have caused the number of plants to be reduced from about 50 in the mid- thirties to the 6 now operating. In addition to this group, a few oven plants formerly practicing full recovery have retained the carbonizing equipment and produce only charcoal. -

Bibliography of Wood Distillation

Bibliography of WoodDistillation T.CL[). Compiled by Gerald A.Walls Arranged by Morrie Craig BibliographY 5 October 1966 For.stProductsResearch FOREST RESEARCHLABORATORY OREGON STATEUNIVERSITY Corvallis PROGRAM AND PURPOSE The Forest Research Laboratoryof the School of Forestry combines a well-equipped laboratory witha staff of forest and wood scientists in program designed to improve the forestresource and promote full uti- lization of forest products. Theextensive research done by the Labora tory is supported by the forest industryand by state and federal funds. The current report results fromstudies in forest products, where wood scientists and technologists,chemists, and engineers are con- cerned with properties, processing,utilization, and marketing of wood and of timber by-products. The PROGRAM of research includes identifying and developing chemicals fromwood, improving pulping of wood and woodresidues, investigating and improving manufacturingtechniques, extending life of wood by treating, developing better methods ofseasoning wood for higher quality and reduced costs, cooperating with forest scientists to determineeffects of growing conditionson wood properties, and evaluating engineering properties ofwood and wood- based materials and structures. The PURPOSE of researchon forest products is to expand markets, create new jobs, and bringmore dollar returns, thus advancing the interests of forestry and forestindustries, by > developing products from residuesand timber now wasted, and > improving treatment and designof present wood products. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 BOOKS 4 ARTICLES AND BULLETINS 5 PATENTS 46 Australia 46 Austria 46 Be1giun 46 Canada 47 Czechoslovakia 47 Denmark 47 France 47 Germany 51 Great Britain 52 India 55 Italy 55 Japan 55 Netherlands 56 Norway 56 Poland 56 Russia 56 Spain 57 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United States 59 Bibliography of Wood Distillation INTRODUCTION This bibliography is a revision and extension to1964 of Bibli- ography of Wood Distillation, 1907-1953published in 1955. -

Hydrogen Sulfide Public Health Statement

PUBLIC HEALTH STATEMENT Hydrogen Sulfide Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences December 2016 This Public Health Statement summarizes what is known about hydrogen sulfide such as possible health effects from exposure and what you can do to limit exposure. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies the most serious hazardous waste sites in the nation. These sites make up the National Priorities List (NPL) and are sites targeted for long-term federal clean-up activities. U.S. EPA has found hydrogen sulfide in at least 34 of the 1,832 current or former NPL sites. The total number of NPL sites evaluated for hydrogen sulfide is not known. But the possibility remains that as more sites are evaluated, the sites at which hydrogen sulfide is found may increase. This information is important because these future sites may be sources of exposure, and exposure to hydrogen sulfide may be harmful. If you are exposed to hydrogen sulfide, many factors determine whether you’ll be harmed. These include how much you are exposed to (dose), how long you are exposed (duration), and how you are exposed (route of exposure). You must also consider the other chemicals you are exposed to and your age, sex, diet, family traits, lifestyle, and state of health. WHAT IS HYDROGEN SULFIDE? Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a flammable, colorless gas that smells like rotten eggs. People usually can smell hydrogen sulfide at low concentrations in air, ranging from 0.0005 to 0.3 parts hydrogen sulfide per million parts of air (ppm). At high concentrations, a person might lose their ability to smell it. -

H2CS) and Its Thiohydroxycarbene Isomer (HCSH

A chemical dynamics study on the gas phase formation of thioformaldehyde (H2CS) and its thiohydroxycarbene isomer (HCSH) Srinivas Doddipatlaa, Chao Hea, Ralf I. Kaisera,1, Yuheng Luoa, Rui Suna,1, Galiya R. Galimovab, Alexander M. Mebelb,1, and Tom J. Millarc,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, University of Hawai’iatManoa, Honolulu, HI 96822; bDepartment of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199; and cSchool of Mathematics and Physics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom Edited by Stephen J. Benkovic, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, and approved August 4, 2020 (received for review March 13, 2020) Complex organosulfur molecules are ubiquitous in interstellar molecular sulfur dioxide (SO2) (21) and sulfur (S8) (22). The second phase clouds, but their fundamental formation mechanisms have remained commences with the formation of the central protostars. Tempera- largely elusive. These processes are of critical importance in initiating a tures increase up to 300 K, and sublimation of the (sulfur-bearing) series of elementary chemical reactions, leading eventually to organo- molecules from the grains takes over (20). The subsequent gas-phase sulfur molecules—among them potential precursors to iron-sulfide chemistry exploits complex reaction networks of ion–molecule and grains and to astrobiologically important molecules, such as the amino neutral–neutral reactions (17) with models postulating that the very acid cysteine. Here, we reveal through laboratory experiments, first sulfur–carbon bonds are formed via reactions involving methyl electronic-structure theory, quasi-classical trajectory studies, and astro- radicals (CH3)andcarbene(CH2) with atomic sulfur (S) leading to chemical modeling that the organosulfur chemistry can be initiated in carbonyl monosulfide and thioformaldehyde, respectively (18). -

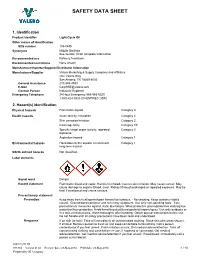

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET 1. Identification Product identifier Light Cycle Oil Other means of identification SDS number 106-GHS Synonyms Middle Distillate See section 16 for complete information. Recommended use Refinery feedstock. Recommended restrictions None known. Manufacturer/Importer/Supplier/Distributor information Manufacturer/Supplier Valero Marketing & Supply Company and Affiliates One Valero Way San Antonio, TX 78269-6000 General Assistance 210-345-4593 E-Mail [email protected] Contact Person Industrial Hygienist Emergency Telephone 24 Hour Emergency 866-565-5220 1-800-424-9300 (CHEMTREC USA) 2. Hazard(s) identification Physical hazards Flammable liquids Category 3 Health hazards Acute toxicity, inhalation Category 4 Skin corrosion/irritation Category 2 Carcinogenicity Category 1B Specific target organ toxicity, repeated Category 2 exposure Aspiration hazard Category 1 Environmental hazards Hazardous to the aquatic environment, Category 1 long-term hazard OSHA defined hazards Not classified. Label elements Signal word Danger Hazard statement Flammable liquid and vapor. Harmful if inhaled. Causes skin irritation. May cause cancer. May cause damage to organs (Blood, Liver, Kidney) through prolonged or repeated exposure. May be fatal if swallowed and enters airways. Precautionary statement Prevention Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. - No smoking. Keep container tightly closed. Ground/bond container and receiving equipment. Use only non-sparking tools. Take precautionary measures against static discharges. Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection. Avoid breathing dust/fume/gas/mist/vapors/spray. Use only outdoors or in a well-ventilated area. Wash thoroughly after handling. Obtain special instructions before use. Do not handle until all safety precautions have been read and understood. -

Exploring the Potential of Nitric Oxide and Hydrogen Sulfide (NOSH)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research City College of New York 2020 Exploring the Potential of Nitric Oxide and Hydrogen Sulfide (NOSH)-Releasing Synthetic Compounds as Novel Priming Agents against Drought Stress in Medicago sativa Plants Chrystalla Antoniou Cyprus University of Technology Rafaella Xenofontos Cyprus University of Technology Giannis Chatzimichail Cyprus University of Technology Anastasis Christou Agricultural Research Institute Khosrow Kashfi CUNY City College See next page for additional authors How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/777 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Authors Chrystalla Antoniou, Rafaella Xenofontos, Giannis Chatzimichail, Anastasis Christou, Khosrow Kashfi, and Vasileios Fotopoulos This article is available at CUNY Academic Works: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/777 biomolecules Article Exploring the Potential of Nitric Oxide and Hydrogen Sulfide (NOSH)-Releasing Synthetic Compounds as Novel Priming Agents against Drought Stress in Medicago sativa Plants Chrystalla Antoniou 1, Rafaella Xenofontos 1, Giannis Chatzimichail 1, Anastasis Christou 2, Khosrow Kashfi 3,4 and Vasileios Fotopoulos 1,* 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology and Food Science, Cyprus University of Technology, 3603 Lemesos, Cyprus; [email protected]