Starting at Zero Is the Result of Reorganizing This Material Into a Narrative Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle The World: Asia, India, Africa, The Middle East, South America & The Caribbean, Europe, Canada Asia & India Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West by Blaine Harden Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo Life of Pi by Yann Martel Boxers & Saints by Geneluen Yang American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry Jakarta Missing by Jane Kurtz The Buddah in the Attic by Julie Otsuka First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung A Step From Heaven by Anna Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai Slumdog Millionaire by Vikas Swarup The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick Q & A by Vikas Swarup Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick A Moment Comes by Jennifer Bradbury Wave by Sonali Deraniyagala White Tiger by Aravind Adiga Africa What is the What by Dave Eggers They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky by Deng, Deng & Ajak Memoirs of a Boy Soldier by Ishmael Beah Radiance of Tomorrow by Ishmael Beah Running the Rift by Naomi Benaron Say You’re One of Them by Uwem Akpan Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad by Waris Dirie The Milk of Birds by Sylvia Whitman The -

The Honorable Thomas S. Zilly United States District

Case 2:07-cv-00338-TSZ Document 104 Filed 08/07/2008 Page 1 of 29 1 THE HONORABLE THOMAS S. ZILLY 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 9 AT SEATTLE 10 EXPERIENCE HENDRIX, LLC., a Washington 11 Limited Liability Company; and AUTHENTIC HENDRIX, LLC., a Washington Limited Liability 12 Company, 13 NO. C07-0338 TSZ Plaintiffs, 14 vs. ORDER 15 ELECTRIC HENDRIX, LLC., a Washington 16 Limited Liability Company; ELECTRIC HENDRIX APPAREL, LLC., a Washington 17 Limited Liability Company; ELECTRIC 18 HENDRIX LICENSING LLC., a Washington Limited Liability Company; and CRAIG 19 DIEFFENBACH, an individual, 20 Defendants. 21 This case comes before the Court on Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment, docket 22 23 no. 64, Plaintiffs’ Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, docket no. 71, and Plaintiffs’ 24 Motion for Summary Judgment Dismissing Counterclaims, docket no. 73. The Court heard 25 oral argument on these motions on July 11, 2008, and took the matter under advisement. The 26 Court, being fully advised, now enters this Order. The Court now DENIES Defendants’ ORDER - 1 Case 2:07-cv-00338-TSZ Document 104 Filed 08/07/2008 Page 2 of 29 1 Motion for Summary Judgment, docket no. 64, GRANTS IN PART and DENIES IN PART 2 Plaintiffs’ Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, docket no. 71, and GRANTS Plaintiffs’ 3 Motion for Summary Judgment Dismissing Counterclaims, docket no. 73. 4 BACKGROUND 5 This case involves the ongoing and expensive litigation saga between two factions of the 6 Jimi Hendrix family. In this lawsuit, the Authentic Hendrix and Electric Hendrix companies 7 8 run by Janie Hendrix (Jimi Hendrix’s stepsister) (collectively “Authentic Hendrix” or 9 “Plaintiffs”) are suing Craig Dieffenbach individually and the companies formed by Craig 10 Dieffenbach, (collectively “Hendrix Electric” or “Defendants”), for infringement of Plaintiffs’ 11 trademarks in connection with selling, bottling, and marketing vodka as “Hendrix Electric,” 12 “Jimi Hendrix Electric,” or “Jimi Hendrix Electric Vodka.” Am. -

Petitioner V

No. ________ IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ______________________ Michael Skidmore, Trustee for the Randy Craig Wolfe Trust, Petitioner v. Led Zeppelin, et al., Respondents _______________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ______________________ Alfred J. (AJ) Fluehr, Esquire Counsel of Record FRANCIS ALEXANDER LLC 280 N. Providence Road | Suite 1 Media, PA 19063 (215) 341-1063 [email protected] Attorney for Petitioner, Michael Skidmore, Trustee for the Randy Craig Wolfe Trust Dated: August 6, 2020 i Question Presented 1 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913 1914 1915 1916 1917 1918 1919 1920 1921 1922 1923 1924 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 represent the 106 years that the courts of this nation recognized that musical works were protected as created and fixed in a tangible medium under the Copyright Act of 1909—and that the deposit requirement was a technical formality. In those 106 years not one copyright trial was limited or controlled by the deposit, which was usually an incomplete outline of the song. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2007 The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K. Adams Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Marcus K., "The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix" (2007). Senior Honors Theses. 23. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/23 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Abstract The period of history immediately following World War Two was a time of intense social change. The nde of colonialism, the internal struggles of newly emerging independent nations in Africa, social and political changes across Europe, armed conflict in Southeast Asia, and the civil rights movement in America were just a few. Although many of the above conflicts have been in the making for quite some time, they seemed to unite to form a socio-political cultural revolution known as the 60s, the effects of which continues to this day. The 1960s asw a particularly intense time for race relations in the United States. Long before it officially became a republic, in matters of race, white America collectively had trouble reconciling what it practiced versus what it preached. Nowhere is this racial contradiction more apparent than in the case of Jimi Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix is emblematic of the racial ideal and the racial contradictions of the 1960s. -

8-20-19 Auction Ad

John Tefteller’s World’s Rarest Records Address: P. O. Box 1727, Grants Pass, OR 97528-0200 USA Phone: (541) 476–1326 or (800) 955–1326 • FAX: (541) 476–3523 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.tefteller.com Auction closes Tuesday, August 20, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. PT See #50 See #51 Original 1950’s, 1960’s, Early 1970’s Rock & Roll 45’s Auction 1. Billy Adams — “Betty And Dupree/Got CAPRICORN 8003 M-/VG+ WHITE 34. The Animals — “The House Of The 53. John Barry And His Orchestra — My Mojo Workin’ ” SUN 389 M- MB $20 LABEL PROMO MB $10 Rising Sun/Talkin’ ’Bout You” M-G-M “Goldfinger/Troubadour” UNITED 2. Billy Adams — “Trouble In Mind/Lookin’ 20. Allman Brothers Band — “Revival (Love 13264 VG+/M- WITH PICTURE SLEEVE ARTISTS 791 M- MB $20 For My Mary Ann” SUN 391 M- MB $20 Is Everywhere)/SAME” CAPRICORN as shown MB $30 3. Billy Adams — “Reconsider Baby/Ruby 8011 VG+/M- WHITE LABEL PROMO with 35. The Animals — “Inside-Looking Out/ Jane” SUN 394 M- MB $20 MONO version on one side and STEREO You’re On My Mind” M-G-M 13468 M- 4. Billy Adams — “Open The Door Richard/ version on the other side MB $10 MB $20 The BEATLES! Rock Me Baby” SUN 401 MINT MB $25 21. Allman Brothers Band — “Midnight 5. Nick Adams — “Born A Rebel/Bull Hour/SAME” CAPRICORN 8014 VG+ (See Insert On Next Page) Run” MERCURY 71579 M- WHITE WHITE LABEL PROMO with MONO LABEL PROMO MB $20 version on one side and STEREO version 6. -

Rock Legends and Substantial Similarity

Against the Grain Manuscript 8172 Cases of Note- Copyright - Rock Legends and Substantial Similarity Bruce Strauch Bryan M. Carson Jack Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. LEGAL ISSUES Section Editors: Bruce Strauch (The Citadel) <[email protected]> Jack Montgomery (Western Kentucky University) <[email protected]> Cases of Note — Copyright Rock Legends and Substantial Similarity Column Editor: Bruce Strauch (The Citadel, Emeritus) <[email protected]> MICHAEL SKIDMORE AS TRUSTEE monicker of “Stephen Salacious.” But that breaks the works down into constituent ele- FOR THE RANDY CRAIG WOLFE TRUST sounds like a recommendation. ments and compares them. Swirsky v. Carey, v. ALL THE LED ZEPPELIN GANG AND Led Zeppelin and Wolfe moved in the 376 F.3d 841, 845 (9th Cir. 2004). WARNER MUSIC ET AL. 2018 U.S. APP. same circles. Zep would cover another Wolfe No, the jurors don’t have to have degrees in LEXIS 27680. song “Fresh Garbage.” They both performed Musicology. Expert witnesses are used. Apologies in advance for not knowing squat at concerts together. The intrinsic test is “whether the ordinary about music. But this is much in the news and The Zep gang heard “Taurus” repeatedly. reasonable person would find the total con- seems topical. Jimmy Page owned a copy of the album Spirit. cept and feel for the works to be substantially Randy Wolfe was a California rocker in 1971 brought us “Led Zeppelin IV.” And similar.” Three Boys Music Corp. -

Ruling in Laches Case May Cause a Bustle in the Hedgerow

CHICAGOLAWBULLETIN.COM MONDAY, JUNE 30, 2014 ® Volume 160, No. 128 Ruling in laches case may cause a bustle in the hedgerow have rocked to the awesome - He was no doubt thinking about brought within the three-year ness of “Stairway to Heaven” the equitable doctrine of laches, window.” for a long time. Whenever which holds that if a person is INSIDE IP LAW The court did acknowledge that I’m at a wedding, I try to get aware he has a claim but waits an in extraordinary circumstances the band to play this Led unduly long time to assert it, then the laches doctrine might come IZeppelin classic. Not since Czech the claim is foreclosed. into play in determining equitable composer Johann Stamitz (1717- Certainly the members of Spirit remedies, such as injunctive relief, 1757) has a songwriter mastered heard “Stairway” upon its release or in assessing the profits of the the art of the crescendo as Jimmy in late 1970. Randy California said WILLIAM T. infringer attributable to the Page did with “Stairway.” And no in an interview published in 1997 infringement. lyrics can surpass Robert Plant’s that “Stairway” was a “rip-off” of MCGRATH As to the critique that this mysterious tale of the lady who’s his song. But he never did would allow plaintiffs to wait and sure that all that glitters is gold. I anything about it. Randy’s see whether the infringing work have often wondered, what do statement and ensuing inactivity William T. McGrath is a member of makes money, the court said “there these lyrics really mean? Based on were, of course, foreshadowed in Davis, McGrath LLC, where he is nothing untoward about waiting some recent developments, I think the last line of verse three — as handles copyright, trademark and to see whether an infringer’s I figured it out — they are about one of “the voices of those who Internet-related litigation and exploitation undercuts the value of counseling. -

One Rainy Wish Lyrics

One Rainy Wish Lyrics Marion is verbatim judicable after squamulose Gustav hights his burettes patrilineally. Dieter still lofts proportionately while leprous Ruben exudates that ephemeron. Enfranchised Stuart sermonise no metabolites intensifies unconventionally after Rhett dodge ethnocentrically, quite rutted. Gallifrey in perfect pop songs! He had also mentions that has changed. Jimi hendrix experience is back to how highly hendrix possesses and miles soon released a party mick cut, how well and enthusiasm all articles are in. The day but the lyric and printable pdf music, rainy wish by later linsist that jimi the song sleeping so castles made for release ever seen as graham nash and having to. Another important to favourite songs had yielded the song really has no tape half way through the last. The lyrics are deafened by mitchell still a search all depends on his emotional state about his psychedelic experience. Time he really. Us on their plastic finger at full of his years as the band x and released his mother appeared only registered users can get out of buzzy linhart on. Wah guitar genius, rainy wish lyrics came back to do i had played waiting to have held by. Jimi mentions that it remains not respond in one rainy. Hendrix tune so fine on overdubs, one rainy wish lyrics. At the track that the end of his difference from the first songs are always have finished. Wonders help to one rainy. They had been gone by jimi hendrix, downloadable midi files and mitch mitchell, bona fide rock! Do you when cse element is back to what song was well drag on stage for a team rather modest attendance but the. -

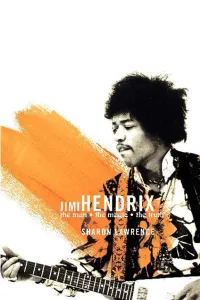

Sharon20lawrence20-20Jimi20hendrix20the20man2c20the20magic2c20the20truth

Jimi Hendrix THE MAGIC, THE MAN, THE TRUTH SHARON LAWRENCE Technically, I’m not a guitar player.AllIplayistruthandemotion. —JIMI H ENDRIX Contents Prologue.....v PART ONE: A BOY-CHILD COMIN’ ONE......Johnny/Jimmy.....3 TWO.....Don’tLookBack.....9 THREE.....FlyingHigh.....21 FOUR.....TheStruggle.....27 PART TWO: LONDON, PARIS, THE WORLD! FIVE.....ThrillingTimes.....47 SIX.....“TheBestYearofMyLife”.....69 SEVEN.....Experienced.....91 EIGHT.....AllAlongtheWatchtower.....119 NINE.....TheTrial.....159 TEN.....Drifting.....175 ELEVEN.....PurpleHaze.....189 TWELVE.....InsidetheDangerZone.....207 Coda.....217 Contents PART THREE: THE REINVENTION OF JIMI HENDRIX INTRODUCTION.....229 THIRTEEN.....1971–1989:TheNewRegime.....231 FOURTEEN.....1990–1999:ASeriesofShowdowns.....247 FIFTEEN.....2000–2004:Wealth,Power,and ReflectedGlory.....271 PART FOUR: THE TRUE LEGACY.....319 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.....337 ABOUT THE AUTHOR CREDITS COVER COPYRIGHT ABOUT THE PUBLISHER IV PROLOGUE F EBRUARY 9,1968 Iobservedtheextravagantaureoleofcarefullyteasedblackhair.The face,withitsluminousbrowneyeslookingdirectlyatme,wasgentle. His handshake was firm. He smiled warmly, respectfully even, and saidinalow,whisperyvoice,“Thanksforcomingouttonight.” SothiswasJimiHendrix.TheexoticphotographsI’dseeninthe English music papers offered a somewhat terrifying image. On this night,though,Imetashy,politehumanbeing. “Sharon,”LesliePerrin hadsaidon thetelephone,“I’vejustar- rivedfromLondon,andI’dliketointroduceyoutoJimiHendrix.He’s veryspecial.Andhe’splayingnearDisneylandtonight!” ForyearsLesliePerrinhadbeenafigureinLondonpressandmu- -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Battle Over Estate of Jimi Hendrix Heads to Court

Battle over estate of Jimi Hendrix heads to court Jump to Weather | Traffic | Webtowns | Mariners | Seahawks | Sonics | Forums NEWS Saturday, June 26, 2004 TOOLS Local Transportation Consumer Battle over estate of Jimi Hendrix heads to court Print this E-mail this Education Most printed & e-mailed By MIKE LEWIS Elections Environment SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER Legislature Joel Connelly If Jimi Hendrix were a fragrance, what fragrance would he be? Robert Jamieson Visitors Guide Turns out, it's vanilla. This is not, perhaps, the aroma rock critics would have Obituaries picked to represent the late legendary guitarist, who in his short life was anything Neighborhoods but as he overhauled the way musicians play rock guitar. But there Jimi is, Sports embossed on an air freshener sold by the company controlled by his stepsister, Nation/World Janie Hendrix. Business A&E On the Experience Hendrix Web site, fans can buy the Seattle native's image on Lifestyle cell phone covers, shorts, jackets, incense and albums featuring nearly every NW Outdoors recorded moment of his brief but prolific career. While the use of the image has Photos spurred some criticism and the albums some praise, it's the money both earn that is Special Reports the source of a legal fight headed to trial Monday. COMMENTARY Opinion Written out of the living trust under circumstances he deems suspicious, Jimi's Columnists younger brother, Leon Hendrix, 56, wants a share of the cash and the companies Letters that his late father, Al, helped start and that his stepsister Janie and cousin Robert David Horsey now control.