The Conflict in Unity State Describing Events Through 1 July 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRC DDG South Sudan Organogram 2016

Nhialdiu Payam Rubkona County // Unity // South Sudan Rapid Site Assessment GPS N 29.68332 // E 09.02619 April 2019 CURRENT CONTEXT LOCATION The DRC RovingCCCM team covers priority Beyond Bentiu Response (BBR) counties within Unity State; Rubkona, Guit and Koch. The team carries out CCCM activities using an area based approach, working through the CCCM cluster to disseminate information. Activities in Nhialdiu on 13th and 14th March 2019 included a multi-sector needs assessment in the area, analysis of displacement situation, mapping of structures and services and meeting with community representatives. For more information, contact Anna Salvarli [email protected] and Ezekiel Duol [email protected] COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP STRUCTURE TOTAL MEMBERS: 25 13 Female 12 Male SITE POPULATION & DISPLACEMENT CONTEXT HUMANITARAIN ACTORS STATE Unity State There are 5 humanitarian actors whose services are accessed in Nhialdiu Payam from the surrounding villages with COUNTY Rubkona County inadequate services. There have been decreased static humanitarian intervention due to insecurity incidents in 2018 in the area. The key services provided and noted were the following: PAYAM Nhialdiu Payam POPULATION 3,262 HHs , 15,036 individuals (IOM DTM March 2019) SITE TYPE Spontaneous returnees (integrated with host community) CCCM DRC (roving team from Bentiu) SITE MANAGER Self managed EDUCATION Mercy Corps (standards 1 to 4, 201 pupils; 120 female, 81 male) FSL None (WHH food assistance) DISPLACEMENT POPULATION HEALTH CASS (National Organization) There is an estimated total of over 800 individuals returnees to Nhialdiu who came between November NUTRITION Cordaid 2018 and March 2019 as per the information given by the local authority. -

Promoting Peace and Resilience in Unity State, South Sudan

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Promoting peace and resilience in Unity state, South Sudan The town of Bentiu, located in Rubkona County, is the comprising 11,529 households.1 Although people capital of the oil-rich Unity state and is predominately living in the PoC site are provided with protection and inhabited by the Nuer people. A series of waterways and humanitarian assistance, they still face challenges swamps cover large parts of the state and these provide including economic hardship, being targeted by armed pasture in the dry season for animals belonging to Nuer groups, violent crime, revenge killings inside the PoC and Dinka pastoralists, as well as other pastoralist site, and outbreaks of disease as a result of the crowded groups from neighbouring Sudan who migrate with conditions in which they live. In July 2020, UNMISS their animals into South Sudan during dry seasons in initiated consultations about its intention to re-designate search of grazing land and water. Unity state also sits the PoC sites in the country to IDP camps and hand over on some of the largest oil deposits in South Sudan and a responsibility of these camps to the government of South considerable amount of petroleum-related activity takes Sudan. People living in the Bentiu PoC site expressed place in and around Bentiu. The production of oil has concern at this plan – while conditions inside the contributed to fuelling conflicts in the state, resulting in camp are very poor, IDPs fear the threat of violence and displacement and environmental degradation. insecurity outside the PoCs if responsibility is transferred. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

ETC Situation Report No 72.Pdf

Republic of South Sudan (RoSS) ETC Situation Report #72 Reporting period 14/04/15 to 27/04/15 ETC RoSS Sitreps are distributed every two weeks. The next report will be issued on or around 11/05/15. Highlights In Bentiu (Unity State), a mission is ongoing in order to provide on-site ICT support and resolve internet connectivity issues experienced during the past weeks. The ETC will also continue to provide ICT Helpdesk services to all humanitarians acting in this area. In Old Fangak (Jonglei State), a front line ETC service deployment assessment mission is planned for the coming week. The ETC is concentrating its efforts on providing emergency response data connectivity, security telecommunication services and renewable power to priority locations identified by the Inter-Cluster Working Group Technician, Bagi Palangako, at work at the ETC Office in Juba (ICWG) in response to the ongoing complex Photo: WFP/George Fominyem crisis. Achievements The ETC continues to support 24x repeater sites for the provision of security telecommunications services. On-site as well as remote ICT support services are being provided to 9x data connectivity sites across the country. In Bor (Jonglei State), a mission was carried out in order to conduce radio programming and provide security telecommunications support to the humanitarians acting in this area. In Ganyiel (Unity State), connectivity issues were reported last week. This week, a successful mission was carried out to replace the faulty equipment. Reliable connectivity is now restored for the humanitarians responding in this area. In Yida (Unity State), a successful mission was completed to determine and resolve the connectivity issues experienced at this location. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team Report Location (State/County/Payam/etc): Unity/Rubkona/Nhialdiu Date of the Mission: 16-25 October 2014 1 Name & Title of Kibrom Tesfaselassie - Nutrition Specialist UNICEF Team Leader 2 Names & Titles (with 1. Elizabeth Mukheb, Child protection UNIDO – Tel No. 0927328405; [email protected] org/depart/section) 2. Hari Vinathan, Nutrition Consultant, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955492068; [email protected] of other members of 3. Luel Deng, Education officer, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955158685; [email protected] 4. Okwera Joseph Okot, Health consultant - Tel no. 0959001482; [email protected] the team 5. Paul Okullu, WASH officer, International Aids Services (IAS), Tel no. 0955963274 3 Sites visited Nhialdiu HQ, Nhialdiu payam, Rubkona County, Unity State GPS; virtually centre of Nhial-Diu:- Latitude : N 09001’19.91’’ Longitude : E 029040’45.44’’ Altitude : 428.4m Information and Data collected 4 General General information about the mission site Information Number of registered people: 40,000 based on WFP verification process for previously given registration card last July. Number of households: over 14,000 including IDPs Total number of children under five (if available): Not Applicable as there was no new registration. Total number of children under 18 years (if available): NA Humanitarian situation and needs (IDPs, last time they received support, who is in control of the area etc.): Nhialdiu is a Payam of Rubkona County consisting of 16 Bomas southwest of Bentiu town approximately 40 km away. As per WFP, this mission covers four/five Payams including IDPs, with a total of population above 40,000. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

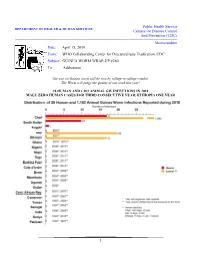

1 Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: April 15, 2019 From: WHO Coll

Public Health Service DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control And Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: April 15, 2019 From: WHO Collaborating Center for Dracunculiasis Eradication, CDC Subject: GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #260 To: Addressees The war on Guinea worm will be won by village-to-village combat. The Worm will judge the quality of our work this year! 28 HUMAN AND 1,102 ANIMAL GW INFECTIONS IN 2018 MALI: ZERO HUMAN CASES FOR THIRD CONSECUTIVE YEAR; ETHIOPIA ONE YEAR 1 Chad reported 96% of all Guinea worms remaining Table 1 in the world in 2018, with 1,040 infected dogs (328 Number of Province District villages), 17 human cases (11 villages) and 25 infected dogs infected cats (20 villages), in a total of 340 villages Chari Baguirmi Mandelia 150 Bailli 129 with one or more Guinea worm infections in Chad Bousso 72 in 2018. Two villages in Salamat Province had 4 Massenya 44 and 3 human cases, respectively. The Guinea worm Dourbali 39 Kouno 21 infected dogs occurred in 21 districts of 7 provinces. Sub Total 455 Moyen Chari Sarh 160 The status of interventions against Guinea worm Kyabe 120 infections in Chad as of the end of 2018 is Danamadji 70 summarized in Figure 3. Chad’s GWEP Korbol 50 implemented monthly Abate treatments in 83 Biobe 9 villages under active surveillance by the end of Sub Total 409 Mayo Kebbi Est Guelendeng 2018, compared to 21 VAS in October-December 142 Bongor 1 2017, and it applied Abate in response to specific Sub Total 143 contamination events in 71 villages, vs. -

Protecting Civilians from Unexploded Ordinance Through Community Engagement and Humanitarian Coordination in Rubkona County, Unity State

Protecting Civilians from Unexploded Ordinance through Community Engagement and Humanitarian Coordination in Rubkona County, Unity State their plots. Thoan, a settlement comprised of approximately 30 households, is located in close proximity to the bridge between Rubkona and Bentiu towns, and served as a strategic military area where government soldiers were stationed during the war. Currently, the barracks are abandoned and returnees from Sudan and Uganda have been moving back into the area, taking advantage of the abandoned infrastructure and the proximity of the river to enable agricultural. In April 2020, NP learned that inter-communal violence and instances of cattle raiding had been disturbing the lives of civilians in the county. Observing that only a few NGOs had interacted with the communities in Thoan, NP’s Beyond Photo: UXO in Thoan/Unity State, South Sudan/2020/NP Bentiu Response (BBR) team conducted a patrol in Thoan to establish a relationship with the When South Sudan descended into civil war in late returnees and assess protection concerns as the 2013, Unity State became a hotspot for hostilities newly formed settlement was also in close with heavy weapons used by all parties to the proximity to a cattle camp. While speaking to a conflict. By the time the signing of the Revitalized female community member who was occupying an Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the abandoned metal corrugated container, during a Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) halted the patrol, the BBR team noticed a pile of bullet heavy fighting in late 2018, large territories of casings beside her shelter. -

Amplifying People's Voices to Contribute to Peace and Resilience

BRIEF / MARCH 2021 Amplifying people’s voices to contribute to peace and resilience in Warrap, South Sudan Warrap state is in the northern part of South Sudan. The clans in the state were high. The governor toured Tonj state borders Unity state to the north-east, Lakes to the North, Tonj South and Gogrial East counties with peace east, Northern Bahr el Ghazal to the north and Western and reconciliation messages and pledged to work closely Bahr el Ghazal to the south. The state is home to the with peace actors in the state. However, violent conflicts Dinka and Bongo ethnic communities. among rival clans in Greater Tonj have intensified, leading to Bona Panek – who was seen as having a ‘soft’ approach The main sources of livelihoods for people in Warrap to communal conflict – being replaced by General Aleu include cattle rearing and small-scale farming, as well Ayieny on 28 January 2021. as beekeeping and wild honey harvesting among the Bongo community in Tonj South County. Cattle rearing Warrap, like many other parts of South Sudan, is is associated with numerous challenges such as cattle experiencing tough economic times. There are multiple raids, stealing, and the need to migrate to neighbouring factors at play, such as political instability in the state communities in search of food and for grazing lands and and in the country, poor road connections, persistent water for animals. In recent years, Warrap has experienced intercommunal violence, and hyperinflation compounded unprecedented intercommunal conflicts, violent cattle by a decline in the purchasing power of the South raiding fuelled by the proliferation of small arms and light Sudanese pound. -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES ..................................................................................................................................................................