Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Words on Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eccentricities of a Nightingale by Tennessee Williams

The Eccentricities of a Nightingale by Tennessee Williams April 9-25 AUDIENCE GUIDE Compiled, Written and Edited by Jack Marshall About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, and neglected American dramatic works of the Twentieth Century… what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past artists, nor can we afford to lose our mooring to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all citizens, of all ages and all points of view. These Audience Guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. Like everything we do to keep alive and vital the great stage works of the Twentieth Century, these study guides are made possible in great part by the support of Arlington County’s Cultural Affairs Division and the Virginia Commission for the Arts. 2 Table of Contents The Playwright 444 Comparing Summer and Smoke 7 And The Eccentricities of a Nightingale By Richard Kramer “I am Widely Regarded…” 12 By Tennessee Wiliams Prostitutes in American Drama 13 The Show Must Go On 16 By Jack Marshall The Works of Tennessee Williams 21 3 The Playwright: Tennessee Williams [The following biography was originally written for Williams when he was a Kennedy Center Honoree in 1979] His craftsmanship and vision marked Tennessee Williams as one of the most talented playwrights in contemporary theater. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

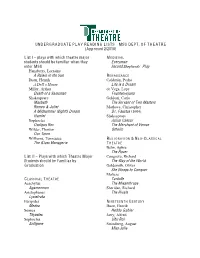

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Seattle Repertory Theatre Records Inventory Accession No: 1481-007

UN IVERSITY U BRARIES w UNIVERSITY of WASHI NGTON Spe ial Colle tions. Seattle Repertory Theatre records Inventory Accession No: 1481-007 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Preliminary Guide to the Seattle Repertory Theatre Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/SeattleRepertoryTheatre1481/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search SEATTLE REPERTORY THEATRE CONTAINER LIST Acc. No. 1481-7 INCL. BOX PaODUCTION BOOKS DATES 1 Day, Clarence.· Life with Father 12/8/74 - 1/2/75 Ibsen, Henrik. Poll's House 2/2 - 2/27/75 Stoppard, Tom. After Magritte/The Real Inspector Hound 3/11/- 4/12/75 Melfi, Leonard. Lunchtime/Halloween 4/21 - 5/19/75 Jones, Preston. The Last of the Knight of 1/11 - 2/5/76 the White Magnolia Lowell, Robert. Benito Cereno 2/24 - 3/7 /76 Orton, Joe. Entertaining Mr. Sloan 3/13 - 3/28/76 Made for T.V. (media improvisation) 4/3 - 4/18/76 Patrick, Robert. Kennedy's Children 4/24 - 5/9/76 Ondaatje, Michael. Billy the Kid 5/15 - 5/30/76 2 O'Neill, Eugene.· Anna Christie 11/4 - 12/9/76 Christie, Agatha·.. The Mousetrap 12/12/76 - 1/6/77 Arbuzov, Aleksei_ Once Upon a Time ca. 1/77 Williams, Tennessee. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof 1/9 - 1/23/77 Bond, Edward. -

Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness: a Representation of Homosexuality in American Drama and Its Adaptations

Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness: A Representation of Homosexuality in American Drama and its Adaptations by Laura Bos s4380770 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Radboud University Nijmegen in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Radboud University 12 January, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. U. Wilbers Bos s4380770/1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction 3 1. Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century America 5 1.1. Homosexuality in the United States: from 1900 to 1960s 5 1.1.1. A Brief History of Sodomy Laws 5 1.1.2. The Beginning of the LGBT Movement 6 1.1.3. Homosexuality in American Drama 7 1.2. Homosexuality in the United States: from 1960s to 2000 9 1.2.1 Gay Liberation Movement (1969-1974) 9 1.2.2. Homosexuality in American Culture: Post-Stonewall 10 2. The Children’s Hour 13 2.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 13 2.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 15 2.3. Adaptations 30 3. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof 35 3.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 35 3.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 37 3.3. Adaptations 49 4. The Boys in the Band 55 4.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 55 4.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 57 4.3. Adaptations 66 Conclusion 73 Works Cited 75 Bos s4380770/2 Abstract This thesis analyzes the presence of homosexuality in American drama written in the 1930s- 1960s by using twentieth-century sexology theories and ideas of heteronormativity, penalization, and explicitness. The following works and their adaptations will be discussed: The Children’s Hour (1934) by Lillian Hellman, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) by Tennessee Williams, and The Boys in the Band (1968) by Mart Crowley. -

Our 88Th Season

ONE SLIGHT HITCH January 15 to February 6, 2016 OUR 88TH Written by Lewis Black • Directed by Omar Kozarsky THE BARN THEATRE P.O. Box 102 It’s Courtney’s wedding day and her mom is making sure that Montville N.J. 07045 everything is perfect. The groom is perfect, the dress is perfect, and Season (973) 334-9320 the decorations (if they arrive) will be perfect. Then—like in any www.barntheatre.org good farce—the doorbell rings and all hell breaks loose. So much for perfect. A surprising comedy from Comedy Central comedian Lewis CROSSING DELANCEY Black. “If sustained laughter is the best measure of a comedy, One September 11 – October 3, 2015 Slight Hitch makes the grade.” –Asbury Park PressAuditions — Written by Susan Sandler • Directed by Susan Binder November 15 & 16, 2015 Presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc This heartwarming romantic comedy tells the story of Isabel, a young woman who lives alone on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. When her irascible granny, Bubbe, elicits the aid of her friend the matchmaker, CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF they find a “good catch” for Isabel in Sam, a pickle vendor with a March 18 to April 9, 2016 heart of gold. Based on the movie of the same name, it is filled with by Tennessee Williams • Directed by Roseann Ruggiero witty New York charm. Step back in time onto the plantation with Maggie, Brick and the family Auditions — July 12 & 13 2015 as they celebrate the 65th birthday of Big Daddy and immerse yourself Presented by special arrangement from Samuel French, Inc. -

University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras Campus College of Humanities Department of English Undergraduate Program – Spring 2012

University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras Campus College of Humanities Department of English Undergraduate Program – Spring 2012 Course Title: Modern Drama: 1940-Present Code: Ingles 4217; Credit Hours 3 Instructor: Dr. Christopher Olsen, E-MAIL: [email protected], phone during office hours 764-0000 (x-7569) or leave message with English Dept. (x-2553). Classes: Mon&Wed; 8:30-9:50am; Office Hours = Mon&Wed, 10-11:30am. Prerequisites: None Text: Plays and essays will be available at Copies Unlimited or you can purchase them on your own. They include Endgame by Samuel Beckett; Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams; The Lover by Harold Pinter; Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? By Edward Albee, Dutchman by Amiri Baraka; Norman Conquests by Alan Ayckbourn; Amadeus by Peter Schaffer; Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet; Suburbia by Eric Begosian; Ruined by Lynn Nottage plus stand-up and performance art pieces. Description: This class is designed to explore many facets of dramatic literature including, studying theatre history and developing performance skills. The class is focused on Modern Drama beginning after World War II until the present. Through analysis and close reading, you will be better prepared to read, understand, and criticize plays. You will also be expected to watch a live performance of a play and write a critique on it. In addition, you will be participating as an actor or director in a series of final scenes at the end of the semester. By the end of the course, it is expected that you will have a strong understanding of different genres of contemporary plays. -

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof PR

Press Contacts: Madelyn Gardner, (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] www.BerkshireTheatreGroup.org Rebecca Brighenti, (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] www.BerkshireTheatreGroup.org NYC Publicist: Richard Kornberg, (212) 944-9444 [email protected] www.kornbergpr.com For immediate release, please: Tuesday, June 7, 2016 BTG Presents Pulitzer and Tony Award-Winning Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Directed by Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-Winning David Auburn Pittsfield, MA – Berkshire Theatre Group and Artistic Director/CEO, Kate Maguire presents Pulitzer and Tony Award-winning production Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, directed by Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning David Auburn, and featuring Michael Raymond-James as Brick. Michael Raymond-James starred in NBC’s recent series, Game of Silence and is best known for his featured roles in True Blood and Once Upon a Time. His films include Black Snake Moan with Justin Timberlake and Jack Reacher with Tom Cruise. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof runs from June 22 through July 16, at The Fitzpatrick Main Stage in Stockbridge, MA. Kate Maguire says, “We are thrilled to have Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning David Auburn (Proof) returning to the Fitzpatrick Main Stage, where he has directed A Delicate Balance, Period of Adjustment and Anna Christie.” Director David Auburn adds, “We will be taking a fresh look at this great American classic with an outstanding company of actors, aiming for a production that’s as unexpected as it is visceral. I’ve worked with Rebecca Brooksher, (BTG: Anna Christie, Period of Adjustment; TV: Elementary, Happyish), many times, going back to the Juilliard School. -

Audition Criteria Band Submission of Completed Application

Audition Criteria Band Submission of Completed Application. Must have had previous class experience in middle school, high school, or private instruction. Be able to play F, B flat, Eb, Ab, Db Major Scales. Be able to play a prepared piece (Etude). Be able to play the Chromatic Scale. Complete a sight reading exercise. Complete basic music skills assessment. Percussion: Mallet percussion should be able to perform the listed major scales and arpeggios two octaves. A solo should be prepared for mallet percussion/ drum percussion. Must complete a departmental interview. Dance Submission of Completed Application. Participate in a class which will include a ballet barre and modern. The purpose of the audition class is to demonstrate the applicant’s technical ability in a variety of dance styles and the ability to take direction. In addition, the student will perform a short solo dance skit not to exceed one minute. The solo must show technique in either ballet, modern, or jazz. Must wear proper dance attire (girls: black leotards and tights. Boys: black dance shorts/tights, fitted t-shirt). Must complete a departmental interview. Guitar Submission of Complete Application. No prior experience need but students will participate in an individual guitar session with the master teacher. Complete a basic music skills assessment. Must complete a departmental interview. Orchestra Submission of Completed Application. Must have had previous class experience in middle school, high school, or private instruction. All instruments must be able to shift to higher positions. Be able to play the Etude provided by Director All instruments – 2 Octave Scales (G and D) memorized with arpeggios. -

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: a History of Erasure and Representation

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: A History of Erasure and Representation While watching the 1958 film Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, a viewer who is unfamiliar with the play may or may not pick up on the homosexual undertones present in the relationship between Brick and Skipper. The close viewer / reader will, however, pick up on the fact that the film has been more or less scrubbed clean of any implication that the two characters may have been lovers, or at the very least, caught up in one-sided attraction. How much of this was influenced by the Motion Picture Production Code in place at the time? And by contrast, how was Tennessee Williams able to write as freely as he did on the subject in the original play? Was film truly that far behind theatre in terms of LGBTQ representation? What strictures and statutes were placed on Williams, if any, while presenting these overt gay themes to the all but completely closeted society of 1950’s America? What was the process by which Williams was able to present his vision, not just in this play, but in others that contained gay characters or relationships? Within the play itself, the ambiguous presentation of gay relationships may somewhat account for the play’s ability to be staged. It can only be argued that Brick is gay or bisexual, in reference to his possible feelings for Skipper and seeming lack of attraction to Maggie—it is never definitively stated. The characters who are more explicitly gay—Skipper and Big Daddy’s friends Jack Straw and Peter Ochello—are only referenced, and never seen on-stage (Williams, 62). -

Theatre Schedule

THEATRE SCHEDULE 2016 Productions 2017 Productions Disney’s Aladdin Jr. The Importance of August 26, 27 & September 2, 3 Being Earnest Sun. Matinees: Aug. 28 & Sept. 4 at 2pm By Oscar Wilde Feb. 10, 11 & 17, 18—2017 Sunday Matinees: Feb. 12 & 19 at 2pm Mother Hicks By Susan Zeder Hedda Gabler October 21, 22, & 28, 29 By Henrik Ibsen Sunday Matinees: Oct. 23 & 30 at 2pm March 24, 25, 31 & April 1—2017 Sun Matinees: Mar. 26, Apr. 2 at 2pm On the Worst Day of Christ- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof mas By Tennessee Williams By Faye Couch Reeves June 2, 3 & 9, 10—2017 December 9, 10 & 16, 17 Sunday Matinees: June 4 & 11 at 2pm Sunday Matinees: Dec. 11 & 18 at 2pm For Tickets to any of our upcoming plays follow this link. Alban Arts Center MEMBERS Board of Directors Jennifer Anderson, Cherie Cowder, President Brian McCann, Libby Londeree, Loren Allen Samantha Miller, Paul Neidbalski Vice President Mandy Shirley, Jenna Skeen, Norman Clerc Nikki Williams Treasurer STAFF Kenneth W. Morrison Adam Bryan Secretary Marlette Carter John Johnson The Alban Arts Center thanks our Producer-Level Sponsor! About Us Loved Ones was established in 1996. For almost two decades, Loved Ones has provided in home personal care and nursing services that are designed to provide a health care option for a variety of patients who would normally be placed in a nursing home or residential care/assisted living facility. Loved Ones Provides Assistance with: • Bathing • Dressing • Grooming • Environmental • Essential Errands • Community Activities • Doctor Appointments • Medication Reminders • And More Clinical studies have proven again and again that patients who are maintained and receive necessary care in the safe, familiar environment of their home, surrounded by their loved ones, have a significantly higher level of general health and quality of life. -

On Cue Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Final.Pdf

EDUCATION On Cue CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Table of Contents About On Cue and STC 2 Curriculum Connections 3 Cast and Creatives 4 The Director in Conversation 5 Synopsis/Context & History 7 Context & History 8 Character Analysis 9 Style and Form 14 Themes and Ideas 18 Elements of Production 22 Reference List 24 Compiled by Jacqui Cowell. The activities and resources contained in this document are designed for educators as the starting point for developing more comprehensive lessons for this production. Jacqui Cowell is the Education Projects Officer for the Sydney Theatre Company. You can contact Jacqui on [email protected]. © Copyright protects this Education Resource. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means in prohibited. How ever, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. 1 About On Cue and STC ABOUT ON CUE ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY STC Ed has a suite of resources located on our website to In 1980, STC’s first Artistic Director Richard Wherrett defined enrich and strengthen teaching and learning surrounding STC’s mission as to provide “first class theatrical entertainment the plays in the STC season. for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun.” Each school show will be accompanied by an On Cue e-publication which will feature essential information for Almost 40 years later, that ethos still rings true. teachers and students, such as curriculum links, information about the playwright, synopsis, character analysis, thematic STC offers a diverse program of distinctive theatre of vision analysis and suggested learning experiences.