Middleton-Voicing the Popular.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

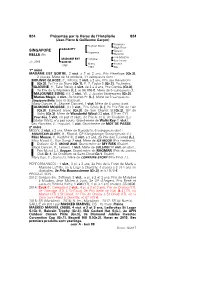

824 Présentée Par Le Haras De L'hotellerie 824 SINGAPORE BELLE (FR)

824 Présentée par le Haras de l'Hotellerie 824 (Jean-Pierre & Guillaume Garçon) Kenmare Highest Honor High River SAGACITY SINGAPORE Sagace Saganeca Haglette BELLE (FR) The Minstrel MADAME EST Longleat Fair Arrow J.b. 2006 SORTIE Missy Frontin 1985 1969 Ma 1re mère MADAME EST SORTIE, 3 vict. à 2 et 3 ans, Prix Pénélope (Gr.3), 2 places. Mère de 14 produits, 11 vainqueurs dont : MOUSSE GLACEE, (f., Mtoto), 2 vict. à 2 ans, Prix des Réservoirs (Gr.3), 2e Prix de Diane (Gr.1), E. P. Taylor S.(Gr.2). Poulinière. MAJOUNE, (f., Take Risks), 4 vict. de 2 à 4 ans, Prix Corrida (Gr.3), 2e Prix de la Pépinière (L.), et 86 896 €. Mère de 5 vainqueurs dt : MAJOUNES SONG, (f.), 2 vict., W. J. Jacobs Stutenpreis (Gr.3). Marias Magic, 4 vict., 3e Steher-Pr. (L.). Mère de 3 vainqueurs. Singapore Belle, (voir ci-dessous). Missy Dancer, (f., Shareef Dancer), 1 vict. Mère de 8 vainq. dont: ALMOND MOUSSE, (f.) 3 vict., Prix Cérès (L.), 2e Prix Fille de l'Air (Gr.3), Edmond Blanc (Gr.3), 3e Sun Chariot St.(Gr.2), GP de Vichy (Gr.3). Mère de Wonderful Wind (13 vict. (17) en ITY). Four Sox, 5 vict. en plat et obst., 3e Prix A. et G. de Goulaine (L.). Stellar Waltz, n’a pas couru. Grand-mère de Waltz Key (1 vict.). Les Planches, (f. Tropular), 1 vict. Grand-mère de MOT DE PASSE. 2e mère MISSY, 2 vict. à 2 ans. Mère de 9 produits, 6 vainqueurs dont : MOUNTAIN GLORY, (f., Ribero), GP Königsberger Steeplechase (L.). -

Tara Stud's Homecoming King

TUESDAY, 15 DECEMBER 2020 DEIRDRE TO VISIT GALILEO IN 2021 TARA STUD'S A new direction in the extraordinary odyssey of the Japanese HOMECOMING KING mare Deirdre (Jpn) (Harbinger {GB}BReizend {Jpn, by Special Week {Jpn}) began on Monday when the 6-year-old left her adopted home of Newmarket to begin her stud career in Ireland. Her first mating is planned to be with Coolmore's champion sire Galileo (Ire). Bred by Northern Farm and raced by Toji Morita, Deirdre's first three seasons of racing were restricted largely to Japan, where she won five races, including the G1 Shuka Sho. She also took third in the G1 Dubai Turf on her first start outside her native country. Following her return visit to the Dubai World Cup meeting in 2019, Deirdre travelled on to Hong Kong and then to Newmarket, which has subsequently remained her base for an ambitious international campaign. Cont. p6 River Boyne | Benoit photo IN TDN AMERICA TODAY VOLATILE SETTLING IN AT THREE CHIMNEYS By Emma Berry and Alayna Cullen GI Alfred G. Vanderbilt H. winner Volatile (Violence) is new to On part of its 70-mile journey across Ireland, the River Boyne Three Chimneys Farm in 2021. The TDN’s Katie Ritz caught up flows not far from Tara Stud in County Meath, but the stallion with Three Chimneys’ Tom Hamm regarding the new recruit. named in its honour has taken a far more meandering course Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. simply to return to source. Approaching his sixth birthday, River Boyne (Ire) (Dandy Man {Ire}) is back home from America and about to embark on a stallion career five years after he was sold by his breeder Derek Iceton at the Goffs November Foal Sale. -

Favorite Music

Favorite Albums of 2008 Lancashire, perfect songwriting and playing topped with that gorgeous voice 1 The Seldom Seen Kid Elbow England alternative singing poetry about daily life LP4 was a huge change for the Icelanders, parts of it actually sound 2 Með Suð í Eyrum Við Spilum Endalaust Sigur Rós Reykjavík, Iceland ambient, post-rock HAPPY, and they pull it off magnificently debut of the year, we all knew it back in January, still sounds great, 3 Vampire Weekend Vampire Weekend New York, NY Upper West Side Soweto every song = potential single was not shown as much critical love as last year's part 1, but I 4 The Stand-Ins Okkervil River Austin, TX lit-rock, neofolk played it a lot and Sheff's the best lyricist in rock Damon Albarn helped produce this excellent record from the blind 5 Welcome to Mali Amadou & Mariam Bamako, Mali world, African married couple, great party music 6 Alight of Night Crystal Stilts Brooklyn, NY garage, shoegaze retro-sounding drone-rock that says turn it up 7 Carried to Dust Calexico Tucson, AZ Americana Southwest border-crossing magical realists never disappoint so shoot me, but I liked it better than the Fleet Foxes record, go 8 Furr Blitzen Trapper Portland, OR neofolk Portland! (the poor man's Seattle) $.49 worth of pure songwriting genius by Replacements' frontman, 9 49:00 of Your Time/Life Paul Westerberg Minneapolis, MN alternative no breaks, no song titles, it's a beautiful mess modern-day Allman Brothers make twang you can love with 10 Brighter than Creation's Dark Drive-By Truckers Athens, GA alt-country -

Bitstream 33779.Pdf (376.6Kb)

Article The Balkans of the Balkans: The Meaning of Autobalkanism in Regional Popular Music Marija Dumnić Vilotijević Institute of Musicology, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 1 June 2020; Published: 16 June 2020 Abstract: In this article, I discuss the use of the term “Balkan” in the regional popular music. In this context, Balkan popular music is contemporary popular folk music produced in the countries of the Balkans and intended for the Balkan markets (specifically, the people in the Western Balkans and diaspora communities). After the global success of “Balkan music” in the world music scene, this term influenced the cultures in the Balkans itself; however, interestingly, in the Balkans themselves “Balkan music” does not only refer to the musical characteristics of this genre—namely, it can also be applied music that derives from the genre of the “newly‐composed folk music”, which is well known in the Western Balkans. The most important legacy of “Balkan” world music is the discourse on Balkan stereotypes, hence this article will reveal new aspects of autobalkanism in music. This research starts from several questions: where is “the Balkans” which is mentioned in these songs actually situated; what is the meaning of the term “Balkan” used for the audience from the Balkans; and, what are musical characteristics of the genre called trepfolk? Special focus will be on the post‐ Yugoslav market in the twenty‐first century, with particular examples in Serbian language (as well as Bosnian and Croatian). Keywords: Balkan; popular folk music; trepfolk; autobalkanism 1. -

That Persistently Funky Drummer

That Persistently Funky Drummer o say that well known drummer Zoro is a man with a vision is an understatement. TTo relegate his sizeable talents to just R&B drumming is a mistake. Zoro is more than just a musician who has been voted six times as the “#1 R&B Drummer” in Modern Drummer and Drum! magazines reader’s polls. He was also voted “Best Educator” for his drumming books and also “Best Clinician” for the hundreds of workshops he has taught. He is a motivational speaker as well as a guy who has been called to exhort the brethren now in church pulpits. Quite a lot going on for a guy whose unique name came from the guys in the band New Edition teasing him about the funky looking hat he always wore. Currently Zoro drums with Lenny Kravitz and Frankie Valli (quite a wide berth of styles just between those two artists alone) and he has played with Phillip Bailey, Jody Watley and Bobby Brown (among others) in his busy career. I’ve known Zoro for years now and what I like about him is his commitment level... first to the Lord and then to persistently following who he believes he is supposed to be. He is a one man dynamo... and yes he really is one funky drummer. 8 Christian Musician: You certainly have says, “faith is the substance of things hoped Undoubtedly, God’s favor was on my life and a lot to offer musically. You get to express for, the evidence of things not seen.” I simply through his grace my name and reputation yourself in a lot of different situations/styles. -

View Provisional Stallions for 2022 Foals

Published here is the Provisional List of the stallions registered with the EBF for the 2021 Covering Season. Prepared by: The European Breeders’ Fund, Lushington House, Full eligibility of each stallion’s progeny, CONCEIVED IN 2021 IN THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE, (the EBF 119 High Street, Newmarket, Suffolk, CB8 9AE, UK foal crop of 2022), for benefits under the terms and conditions of the EBF, is DEPENDENT UPON RECEIPT INTERNATIONAL OF THE BALANCE OF THE DUE CONTRIBUTION BY 15TH DECEMBER 2021. Late stallion entries for the T: +44 (0) 1638 667960 E: [email protected] EBF will be included in the Final List, provided the full contribution is received by 15th December 2021. www.ebfstallions.com STALLIONS STALLION STANDS ADMIRE MARS (JPN) JPN A C DRAGON PULSE (IRE) GALILEO GOLD (GB) IT’S GINO (GER) MAHSOOB (GB) ORDER OF ST GEORGE (IRE) ROSENSTURM (IRE) SUCCESS DAYS (IRE) WALDPFAD (GER) BRICKS AND MORTAR (USA) JPN ABYDOS (GER) CABLE BAY (IRE) DREAM AHEAD (USA) GALIWAY (GB) IVANHOWE (GER) MAKE BELIEVE (GB) OUTSTRIP (GB) ROSS (IRE) SUMBAL (IRE) WALK IN THE PARK (IRE) CITY OF LIGHT (USA) USA ACCLAMATION (GB) CALYX (GB) DSCHINGIS SECRET (GER) GAMMARTH (FR) IVAWOOD (IRE) MALINAS (GER) P ROYAL LYTHAM (FR) SWISS SPIRIT (GB) WAR COMMAND (USA) DREFONG (USA) JPN ACLAIM (IRE) CAMACHO (GB) DUBAWI (IRE) GAMUT (IRE) J MANATEE (GB) PALAVICINI (USA) RULE OF LAW (USA) T WASHINGTON DC (IRE) DURAMENTE (JPN) JPN ADAAY (IRE) CAMELOT (GB) DUE DILIGENCE (USA) GARSWOOD (GB) JACK HOBBS (GB) MARCEL (IRE) PAPAL BULL (GB) RULER OF THE WORLD (IRE) TAAREEF (USA) WATAR -

INTO the MUSIC ROOMS Kirkland A. Fulk

Introduction INTO THE MUSIC ROOMS Kirkland A. Fulk I want to begin at the end, the end, that is, of the present volume. In his conclusion to the final chapter, Richard Langston remarks on Diedrich Diederichsen’s short music columns published in the Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel between 2000 and 2004. Diederichsen, perhaps Germany’s most well-known music and cultural critic, titled these columns “Musikzim- mer” [the music room]. Here, as Diederichsen put it in his introduction to the 2005 republished collection of these sixty-two, roughly 600-word music columns, he endeavored to bring together as many disparate things as pos- sible under the designation “music.”1 In any one of these music rooms, readers encounter curious and unexpected combinations and constella- tions: the (West) German (post-)punk band Fehlfarben is discussed in con- junction with British mod group Small Faces, Bob Dylan, and Leonard Cohen; the Australian-American feminist music group and performance art ensemble Chicks on Speed is brought together with German hip-hop and reggae musician Jan Delay; and the German avant-garde trio BST (which notably includes the well-known German cultural theorist Klaus Theweleit on guitar) finds a place alongside the jazz collective Art Ensemble of Chicago as well as the pioneering Hamburg indie-rock band Blumfeld. I start this introduction to the subsequent essays on postwar German popular music at the end station of this volume, in Diederichsen’s music rooms, because in many ways they serve as an analogy for what this volume sets out to do, namely traffic in the intersections, entanglements, and flows between the national and transnational. -

Exploring the Chinese Metal Scene in Contemporary Chinese Society (1996-2015)

"THE SCREAMING SUCCESSOR": EXPLORING THE CHINESE METAL SCENE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE SOCIETY (1996-2015) Yu Zheng A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2016 Yu Zheng All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This research project explores the characteristics and the trajectory of metal development in China and examines how various factors have influenced the localization of this music scene. I examine three significant roles – musicians, audiences, and mediators, and focus on the interaction between the localized Chinese metal scene and metal globalization. This thesis project uses multiple methods, including textual analysis, observation, surveys, and in-depth interviews. In this thesis, I illustrate an image of the Chinese metal scene, present the characteristics and the development of metal musicians, fans, and mediators in China, discuss their contributions to scene’s construction, and analyze various internal and external factors that influence the localization of metal in China. After that, I argue that the development and the localization of the metal scene in China goes through three stages, the emerging stage (1988-1996), the underground stage (1997-2005), the indie stage (2006-present), with Chinese characteristics. And, this localized trajectory is influenced by the accessibility of metal resources, the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the progress of modernization in China, and the overall development of cultural industry and international cultural communication. iv For Yisheng and our unborn baby! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

James Brown's 'Funky Drummer'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by edoc Publication server Continuity and Break: James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’ Anne Danielsen, University of Oslo Abstract: In groove-oriented music, the basic unit of the song is repeated so many times that our inclination as listeners to organize the musical material into an overall form gradually fades away. Instead of waiting for events to come, we are submerged in what is before us. Dancing, playing, and listening in such a state of being are not characterized by consideration or reflection but rather by a presence in the here and now of the event. It is likely to believe that there is a connection between such an experience and the ways in which a groove is designed. This article investigates how a groove-based tune, more precisely Funky Drummer by James Brown and his band, is given form in time and, moreover, how this form is experienced while being in such a ‘participatory mode’ (Keil). Of importance is also to discuss how the rhythmic design of the groove at a microlevel contributes to this experience. In groove-oriented music, the basic unit of the song is repeated so many times that our inclination as listeners to organize the musical material into an overall form gradually fades away. Instead of waiting for events to come, we are submerged in what is before us. Our focus turns inward, as if our sensibility for details, for timing inflections and tiny timbral nuances, is inversely proportional to musical variation on a larger scale. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

1 Million+ EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS

2018 KEENELAND SATURDAY, 2ND JUNE 2018 SEPTEMBERYEARLING SALE SEPTEMBERYEARLING SALE In 2017: 73 individual buyers spent Monday, September 10 to Saturday, September 22 EBN $1 million+ EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU RACING PREVIEW | STAKES RESULTS | SALES TALK | STAKES FIELDS TODAY’S HEADLINES RACING REVIEW FOREVER ON TOP: O’BRIEN WINS HIS SEVENTH OAKS Aidan O’Brien saddled five of the nine runners in the Gr.1 Oaks and it was the mount of his son Donnacha, Forever Together, who came out on top, breaking her maiden tag in the process. The result gave the trainer his seventh victory in the race, the first Forever Together (Galileo) stretches away from having come with Shahtoush (Alzao) in 1998. Wild Illusion (Dubawi) to win the Gr.1 Oaks and The daughter of Galileo raced in mid-division as her pace- break her maiden tag in the process. © Steve Cargill setting stable companion Bye Bye Baby (Galileo) raced into a The winner had raced twice as a juvenile, finishing fourth and significant advantage. As they turned for home, Forever Together quickly switched across to the stands-side rail, as did the favourite third in a pair of mile maidens at Naas and Leopardstown and Wild Illusion (Dubawi), while Bye Bye Baby stayed central. The made her seasonal reappearance when second to Magic Wand in pair on the rail soon passed the long-time leader and looked to the Listed Cheshire Oaks last month. battle it out together, but Forever Together stayed on much the O’Brien said: “Forever Together is a staying filly who gets the trip stronger and scored by a comfortable four and a half lengths very well and is obviously by Galileo, which is a massive advantage. -

Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, Non-Member; $1.35, Member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; V15 N1 Entire Issue October 1972

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 691 CS 201 266 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Science Fiction in the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMKen Donelson, Ed., Arizona English Bulletin, English Dept., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, Ariz. 85281 ($1.50); National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, non-member; $1.35, member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v15 n1 Entire Issue October 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Booklists; Class Activities; *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Reading Materials; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Heinlein (Robert) ABSTRACT This volume contains suggestions, reading lists, and instructional materials designed for the classroom teacher planning a unit or course on science fiction. Topics covered include "The Study of Science Fiction: Is 'Future' Worth the Time?" "Yesterday and Tomorrow: A Study of the Utopian and Dystopian Vision," "Shaping Tomorrow, Today--A Rationale for the Teaching of Science Fiction," "Personalized Playmaking: A Contribution of Television to the Classroom," "Science Fiction Selection for Jr. High," "The Possible Gods: Religion in Science Fiction," "Science Fiction for Fun and Profit," "The Sexual Politics of Robert A. Heinlein," "Short Films and Science Fiction," "Of What Use: Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "Science Fiction and Films about the Future," "Three Monthly Escapes," "The Science Fiction Film," "Sociology in Adolescent Science Fiction," "Using Old Radio Programs to Teach Science Fiction," "'What's a Heaven for ?' or; Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "A Sampler of Science Fiction for Junior High," "Popular Literature: Matrix of Science Fiction," and "Out in Third Field with Robert A.