Agents of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UKRAINE the Constitution and Other Laws and Policies Protect Religious

UKRAINE The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom and, in practice, the government generally enforced these protections. The government generally respected religious freedom in law and in practice. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. Local officials at times took sides in disputes between religious organizations, and property restitution problems remained; however, the government continued to facilitate the return of some communal properties. There were reports of societal abuses and discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. These included cases of anti-Semitism and anti- Muslim discrimination as well as discrimination against different Christian denominations in different parts of the country and vandalism of religious property. Various religious organizations continued their work to draw the government's attention to their issues, resolve differences between various denominations, and discuss relevant legislation. The U.S. government discusses religious freedom with the government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. U.S. embassy representatives raised these concerns with government officials and promoted ethnic and religious tolerance through public outreach events. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 233,000 square miles and a population of 45.4 million. The government estimates that there are 33,000 religious organizations representing 55 denominations in the country. According to official government sources, Orthodox Christian organizations make up 52 percent of the country's religious groups. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate (abbreviated as UOC-MP) is the largest group, with significant presence in all regions of the country except for the Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, and Ternopil oblasts (regions). -

NEWSLETTER October 17, 2017

NEWSLETTER October 17, 2017 Three Administrative Service Centres were opened in Amalgamated Territorial Communities with the support of the Programme U-LEAD with Europe Modern ASCs are now operating in Tyachiv ATC, Zakarpattya oblast, Kipti ATC, Chernihiv oblast, and in Hostomel community, Kyiv oblast. The Centres were established with the support of the Programme U-LEAD with Europe: improving the delivery of local administrative services. The ATC residents will have access to a wide range of administrative services provided by different local and state agencies, including the most in-demand ones such as housing subsidies, social services, pension services, registration of residence and removal of residence registration, land services, real estate registration and, as in the case with Tiachiv ASC, even issuance of national ID-cards and passports for travelling abroad. U-LEAD with Europe Programme provided institutional support, renovation of the ASC premises and procurement of software. Furthermore, the ASC employees took part in the Programme’s advanced five-module training and activities for citizen engagement and awareness raising were also organised. Revenues from the administrative services will be credited to the ATC budgets. First results of the U-LEAD with Europe: Improving the Delivery of Local Services Programme: Community Oblast Number of services Number of residents to use provided by ASC administrative services provided by ASC Tyachiv ATC Zakarpattya 60 20 145 Kipti ATC Chernihiv 100 3 879 Hostomel community Kyiv 48 24 500 ASC Launch Schedule Next ASCs will be opening on the following dates: October Mokra Kalyhirka, Cherkassy Oblast - 19 October Novi Strilyshcha, Lviv Oblast - 25 October November Kalyta, Kyiv Oblast - 1 November Erky, Cherkassy Oblast - 2 November. -

Hybrid Threats to the Ukrainian Part of the Danube Region

Hybrid threats to the Ukrainian part of the Danube region Artem Fylypenko, National Institute for Strategic Studies Ukraine, Odesa 2021 What are the hybrid threats? What are main characteristics of the Ukrainian part of the Danube region, its strength and weaknesses, it`s vulnerability to hybrid threats? How hybrid activities are carried out in practice? What are the hybrid threats? "Hybrid threats combine military and "The term hybrid threat refers to an non-military as well as covert and action conducted by state or non-state overt means, including disinformation, actors, whose goal is to undermine or harm a target by influencing its cyber attacks, economic pressure, decision-making at the local, regional, deployment of irregular armed groups state or institutional level. Such and use of regular forces. Hybrid actions are coordinated and methods are used to blur the lines synchronized and deliberately target between war and peace, and attempt democratic states’ and institutions’ to sow doubt in the minds of target vulnerabilities. Activities can take place, for example, in the political, populations. They aim to destabilise economic, military, civil or information and undermine societies." domains. They are conducted using a wide range of means and designed to Official website of NATO remain below the threshold of detection and attribution." The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats The Ukrainian part of the Danube region Weaknesses of the Ukrainian part of the Danube region Zakarpattia oblast Ivano-Frankivsk Chernivtsi -

OPEN for Investors UKRAINIAN Infrastructure

UKRAINIAN Infrastructure: OPEN for Investors Introduction 3 Sea & river 10 Airports 18 TABLE OF Roads 28 CONTENTS Railways 40 Postal services 46 Electric vehicle infrastructure 50 Partnership 52 Area: GDP (PPP): 603 500 km2. $337 bln in 2017 UKRAINE – Largest country within Europe Top-50 economy globally TRANSIT BRIDGE Population: Workforce: BETWEEN THE 42.8 million people. 20 million people. EU AND ASIA 70% urban-based #1 country in the CEE by the number of engineering graduates Average Salary: €260 per month. Most cost-competitive manufacturing platform in Europe Trade Opportunities: 13 Sea & 19 16 River Airports Geographical center of Europe, making the country an Ports ideal trade hub to the EU, Middle East and Asia Free trade agreement (DCFTA) with the EU and member of the WTO Free trade: EU, CIS, EFTA, FYROM, Georgia, Montenegro. Ongoing negotiations with Canada, Israel, 170 000 km 22 000 km Turkey of Roads of Railways 3 Last year, the Ukrainian Government prepared a package of planned reforms to bring changes to Ukraine’s infrastructure. The scale of the package is comparable only with the integration of Eastern European countries into the European Union’s infrastructure in the 1990’s and 2000’s. The Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine has already begun implementing these reforms, embracing all the key areas of the country’s infrastructure - airports, roadways, railways, sea and river ports, and the postal service: • Approximately 2177 kilometers of roadways have been constructed in 2017, and more than 4000 kilometers (state roads) are to be completed in 2018, improving the transportation infrastructure; • A number of investment and development agreements were signed in 2017. -

Human Potential of the Western Ukrainian Borderland

Journal of Geography, Politics and Society 2017, 7(2), 17–23 DOI 10.4467/24512249JG.17.011.6627 HUMAN POTENTIAL OF THE WESTERN UKRAINIAN BORDERLAND Iryna Hudzelyak (1), Iryna Vanda (2) (1) Chair of Economic and Social Geography, Faculty of Geography, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Doroshenka 41, 79000 Lviv, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) (2) Chair of Economic and Social Geography, Faculty of Geography, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Doroshenka 41, 79000 Lviv, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] Citation Hudzelyak I., Vanda I., 2017, Human potential of the Western Ukrainian borderland, Journal of Geography, Politics and Society, 7(2), 17–23. Abstract This article contains the analysis made with the help of generalized quantative parameters, which shows the tendencies of hu- man potential formation of the Western Ukrainian borderland during 2001–2016. The changes of number of urban and rural population in eighteen borderland rayons in Volyn, Lviv and Zakarpattia oblasts are evaluated. The tendencies of urbanization processes and resettlement of rural population are described. Spatial differences of age structure of urban and rural population are characterized. Key words Western Ukrainian borderland, human potential, population, depopulation, aging of population. 1. Introduction during the period of closed border had more so- cial influence from the West, which formed specific Ukraine has been going through the process of model of demographic behavior and reflected in dif- depopulation for some time; it was caused with ferent features of the human potential. significant reduction in fertility and essential mi- The category of human potential was developed gration losses of reproductive cohorts that lasted in economic science and conceptually was related almost a century. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Annual Report 2017___15.08.2018 Final.Indd

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ALLIANCE FOR PUBLIC HEALTH 2017 I am honored to present the report on the activities of Alliance for Public Health in 2017. This year Alliance – one of the biggest civil society organizations in Ukraine – successfully implemented national and international programs to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and hepatitis. Thanks to the efforts of Alliance and its partner organizations aimed at the key populations vulnerable to HIV, over 300 thousand clients were covered with our programs. It became the determinant, which allowed curbing the epidemic in Ukraine. Our expertise was highly praised when establishing the Global HIV Prevention Coalition. Alliance works hard to achieve the global 90-90-90 targets, in particular through scaling up the access to HIV testing. In late 2017, Alliance in collaboration with the Network of PLWH launched the campaign “HIV is Invisible, Get Tested and Save Life!” to promote a unique approach of self-testing. Any person could order and receive by post a free HIV self-test through the website www.selftest.org.ua. In 2017, Alliance was the first in Ukraine to introduce pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programs with support of CDC/PEPFAR and launch innovative programs for adolescents together with Elton John AIDS Foundation. 2017 was a special year for us as it gave start to the “transition period”: we began the handover of opioid substitution treatment program for over 10,000 patients to the government. Ten years ago, in a similar way Alliance handed over to the state the ART program to treat people living with HIV. Since then, there has been a huge scale-up of this program and we expect that it will be the same with the substitution treatment program, considering that the real demand is much higher – at least 50,000 patients are in need of OST. -

April 16, 2020 Dear TOUCH Sponsors and Donors, Our Last Update

April 16, 2020 Dear TOUCH Sponsors and Donors, Our last update was on March 5, 2020. So much has changed in our world since that time. On that March date, only a few weeks ago, the COVID19 statistics globally were: • Number of cases: 97,500 • Number of deaths: 3,345 individuals As of today, April 16, the number of worldwide cases and deaths have skyrocketed to: • Number of cases: 2,150,000 • Number of deaths: 142,000 individuals Ukraine is included in those statistics. Uzhhorod is the government center of the Transcarpathia (Zakarpattia) Oblast. An oblast is like a “state” in the US and there are 24 oblasts in Ukraine. This is the current information for both Zakarpattia Oblast and for Ukraine: In the Zakarpattia Oblast Confirmed Cases Recovered Deaths 116 12 2 In Ukraine Confirmed Cases Recovered Deaths 4,161 186 116 Many of you asked how the children and people of Uzhhorod were doing. We have asked questions to our friends, medical contacts, and program directors to get answers. Here is a summary information we have received from them over the last few days: • Uzhhorod is in “shutdown” similar to what we are doing in the US • Borders between Ukraine and other countries are closed and there is no public transportation in towns, between cities or regions. • Restaurants, non-essential businesses, public schools, Uzhhorod National University, and public transportation have all been closed since mid-March. • Grocery stores, gas stations and pharmacies are open. • After April 6, citizens over 60 were asked to remain at home and groups of more than 2 individuals are not allowed without a good reason. -

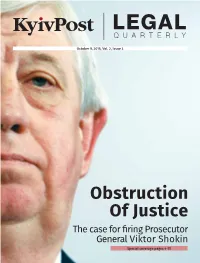

The Case for Firing Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin

October 9, 2015, Vol. 2, Issue 3 Obstruction Of Justice The case for fi ring Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin Special coverage pages 4-15 Editors’ Note Contents This seventh issue of the Legal Quarterly is devoted to three themes – or three Ps: prosecu- 4 Interview: tors, privatization, procurement. These are key areas for Ukraine’s future. Lawmaker Yegor Sobolev explains why he is leading drive In the fi rst one, prosecutors, all is not well. More than 110 lawmakers led by Yegor Sobolev to dump Shokin are calling on President Petro Poroshenko to fi re Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin. Not only has Shokin failed to prosecute high-level crime in Ukraine, but critics call him the chief ob- 7 Selective justice, lack of due structionist to justice and accuse him of tolerating corruption within his ranks. “They want process still alive in Ukraine to spearhead corruption, not fi ght it,” Sobolev said of Shokin’s team. The top prosecutor has Opinion: never agreed to be interviewed by the Kyiv Post. 10 US ambassador says prosecutors As for the second one, privatization, this refers to the 3,000 state-owned enterprises that sabotaging fi ght against continue to bleed money – more than $5 billion alone last year – through mismanagement corruption in Ukraine and corruption. But large-scale privatization is not likely to happen soon, at least until a new law on privatization is passed by parliament. The aim is to have public, transparent, compet- 12 Interview: itive tenders – not just televised ones. The law, reformers say, needs to prevent current state Shabunin says Poroshenko directors from looting companies that are sold and ensure both state and investor rights. -

Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine

Public Council of All-Ukrainian Environmental NGOs under the aegis of the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of Ukraine Organising Committee of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs for preparation to Fifth Pan-European Ministerial Conference "Environment for Europe" Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine Report of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs Кyiv — 2003 Public Evaluation of Environmental Policy in Ukraine. Report of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs. — Kyiv, 2003. — 139 pages The document is prepared by the Organising Committee of Ukrainian Environmental NGOs in the framework of the «Program of Measures for Preparation and Conduction of 5th Pan-European Ministerial Conference» «Environment for Europe» for 2002–2003» approved by the National Organising Committee of Ukraine. Preparation and publication of the report was done wit the support of: Regional Ecological Center - REC-Kyiv; Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources of Ukraine; Milieukontakt Oost Europa in the framework of the project «Towards Kyiv-2003» with financial support of the Ministry of Territorial Planning, Construction and the Environment; UN office in Ukraine Contents Foreword . 1. Environmental Policy and Legislation . 1.1. Legislative Background of Environmental Policy . 1.2. Main State Documents Defining Environmental Policy . 1.3. Enforcement of Constitution of Ukraine . 1.4. Implementation of Environmental Legislation . 1.5. State of Ukrainian Legislation Reforming after Aarhus Convention Ratification . 1.6.Ukraine's Place in Transition towards Sustainable Development . 2. Environmental Management . 2.1. Activities of State Authorities . 2.2 Activities of State Control Authorities . 2.3. Environmental Monitoring System . 2.4. State Environmental Expertise . 2.5. Activities of Local Administrations in the Field of Environment . -

Volyn Oblast Q3 2019

Business Outlook Survey ResultsРезультати of surveys опитувань of Vinnitsa керівників region * enterprisesпідприємств managers м. Києва of regarding Volyn і Київської O blasttheir області щодоbusiness їх ділових expectations очікувань* * Q3 2019 I квартал 2018Q2 2018року *Надані результати є*This відображенням survey only reflectsлише думкиthe opinions респондентів of respondents – керівників in Volyn підприємств oblast (top managersВінницької of області в IІ кварталіcompanies) 2018 року who і wereне є прогнозамиpolled in Q3 та201 оцінками9, and does Національного not represent банку NBU forecastsУкраїни. or estimates res Business Outlook Survey of Volyn Oblast Q3 2019 A survey of companies carried out in Volyn oblast in Q3 2019 showed that respondents continued to have high expectations that the Ukrainian economy would grow, and that their companies would continue to develop over the next 12 months. Inflation expectations softened, while depreciation expectations increased. The top managers of companies said they expected that over the next 12 months: . the output of Ukrainian goods and services would grow at a slower pace: the balance of expectations was 38.5% compared with 61.5% in Q2 2019 (Figure 1) and 30.5% across Ukraine . the growth in prices for consumer goods and services would be moderate: most respondents (84.6%) said that inflation would not exceed 10.0% compared with 61.5% in the previous quarter and 73.3% of respondents across Ukraine. Respondents continued to refer to production costs and hryvnia exchange rate fluctuations as the main inflation drivers (Figure 2) . the hryvnia would depreciate at a faster pace: 83.3% of respondents (compared with 76.9% in the previous quarter) expected the hryvnia to weaken against the US dollar, with the figure across Ukraine being 69.0% . -

State Building in Revolutionary Ukraine

STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM This page intentionally left blank Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM STEPHEN VELYCHENKO STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE A Comparative Study of Governments and Bureaucrats, 1917–1922 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2011 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable- based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Velychenko, Stephen State building in revolutionary Ukraine: a comparative study of governments and bureaucrats, 1917–1922/Stephen Velychenko. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 1. Ukraine – Politics and government – 1917–1945. 2. Public adminstration – Ukraine – History – 20th century. 3. Nation-building – Ukraine – History – 20th century 4. Comparative government. I. Title DK508.832.V442011 320.9477'09041 C2010-907040-2 The research for this book was made possible by University of Toronto Humanities and Social Sciences Research Grants, by the Katedra Foundation, and the John Yaremko Teaching Fellowship. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities.