The Master Plan Study for Kenyan Industrial Development (Mapskid) in the Republic of Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

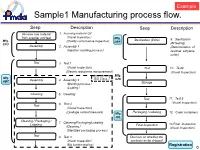

Sample1 Manufacturing Process Flow

Example Sample1 Manufacturing process flow. Seep Description Seep Description Receive raw material 1. Incoming material QC from supplier and test (Visual Inspection) Mfg. Sterilization (EOG) 9. Sterilization Mfg. (Quality conformance inspection) DEF STU (BI testing) Assembly 2. Assembly 1 (Determination of (Injection molding process) residual ethylene oxide) Test 3. Test1 (Visual Inspection) Test 10. Test4 (Electric resistance measurement ) (Visual Inspection) Mfg. Mfg. ISO Class 7 GHI ABC Assembly 4. Assembly 2 (Welding process) Storage (Coating) Cleaning 5. Cleaning Test 11. Test 5 6. Test 2 (Visual Inspection) Test (Visual Inspection) Packaging / Labeling (Leakage current measure) Mfg. 12. Outer containers JKL Cleaning / Packaging / 7. Cleaning/Packaging/Labeling Labeling 13.Final Inspection ( ) Final Inspection Cleaning (Visual Inspection) (Sterilized packaging process) Test 8. Test 3 Decision on whether the (Visual Inspection) products an be shipped (Bio burden testing) Registration 0 Example Sample2 Mutual relations of QMS Marketing Authorization Holder(JKL, Ltd.) Agreement 実地調査QMS(ABC, Co.) MNO, Co.(Registration) Design facility GHI Distribution Center (Inspection・Storage) ABC Mfg. site STU, Mfg. site. (Registration) Assembling plant Main assembling plant Agreement JKL Distribution Center QMS(DEF, Co.) (Registration) :Same QMS (Distribution Center) DEF, Mfg. site(Registration) : (Sterilizer) Information exchange 1 Example Form2 Outline of MAH/RMS (1/2) Outline of manufacturing site As of DD/MM/YY Name of mfg . site Address of mfg. -

11873676.Pdf

Master Plan Study for Kenyan Industrial Development (MAPSKID) Introduction Outline of Master Plan Introduction: Outline of Master Plan (1) Background The Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation (ERS) in 2003 clearly stipulates the “Industrial Transformation to the Year 2020”, (hereinafter referred to as “Sessional Paper”), Sessional Paper No.2 published in 1996 (Revised in 1997), should be reviewed to be developed into a master plan for industrial development (hereinafter referred to as “the Master Plan”). GOK, then, has requested the Government of Japan (hereinafter referred to as “GOJ”) to conduct the study on “Master Plan Study for Kenyan Industrial Development” (hereinafter referred to as “MAPSKID”). In response to the request of GOK, GOJ has decided to conduct MAPSKID, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (hereinafter referred to as “JICA”), the official agency responsible for the implementation of the technical cooperation programmes of GOJ, was commissioned to undertake MAPSKID. JICA set up a team of consultants comprised from Sanyu Consultants Inc. and KRI International Corp. (hereinafter referred to as “the Study Team”) to carry out MAPSKID. (2) Purpose Purposes of MAPSKID are as follows. i) Overall Goal: to promote the industrial development of Kenya with emphasis on the target sub-sectors ii) Project Purpose: to have the Master Plan adopted as a component of ERS to implement Master Plan with initiatives of MOTI and cooperation from the private sector iii) Outputs: to develop the Master Plan comprising a master plan, action plans, and a development plan of the target sub-sectors to transfer skills and knowledge to the counterpart of the counterpart for developing the Master Plan to strengthen the public and private partnership through promoting dialogues (3) Target sectors MAPSKID focuses on the manufacturing sector. -

Billion Billion (99%(99% Vs

Section 1: Results for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2005 Section 2: Restructuring IAB Development and Production Centers July 29, 2005 OMRONOMRON CorporationCorporation 1 Contents Section 1: Results for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2005 1. Executive Summary 2. Results for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2005 3. Forecast for the Six Months Ending Sept. 30, 2005 and Forecast for the Full Year Ending March 31, 2006 Notes: 1. Quarterly financial information is not audited or reviewed by an auditing corporation. 2. The financial statements are prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP. 3. Includes 146 consolidated subsidiaries and 18 affiliated companies accounted for by the equity method. 4. Projections of results and future developments are based on information available to the Company at the present time, as well as certain assumptions judged by the Company to be reasonable. Various factors could cause actual results to differ materially from these projections. Major factors influencing Omron's actual results include, but are not limited to, (i) the economic conditions surrounding the Company's businesses in Japan and overseas, (ii) demand trends for the Company's products and services, (iii) the ability of the Omron Group to develop new technologies and new products, (iv) major changes in the fund-raising environment, (v) tie-ups or cooperative relationships with other companies, and (vi) movements in currency exchange rates and stock markets. 2 Main Business Areas Business Business Name Abbrev. Business Description Industrial Industrial Automation IAB Manufacture and sale of control components for factory automation, etc. Automation Business Electronic Electronic Components ECB Manufacture and sale of electronics Business components for home appliances, Components communications, mobile devices, etc. -

Chapter 7 Upgrading and Diversification of Industrial Structure

Chapter 7 Upgrading and Diversification of Industrial Structure in Lao PDR: Prospect and Challenges Leuam Nhongvongsithi Economic Research Institute of Trade (ERIT), Lao PDR Souknilanh Keola Development Study Center, IDE-JETRO, Japan March 2010 This chapter should be cited as Nhongvongsithi, L. and S. Keola (2010), ‘Upgrading and Diversification of Industrial Structure in Lao PDR: Prospect and Challenges’, in Banomyong, R. and M. Ishida (eds.), A Study on Upgrading Industrial Structure of CLMV Countries. ERIA Research Project Report 2009-7-3, Jakarta: ERIA. pp.285-314. CHAPTER 7 UPGRADING AND DIVERSIFICATION OF INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURE IN LAO PDR: PROSPECT AND CHALLENGES Leuam Nhongvongsithi and Souknilanh Keola Abstract This chapter examines the prospects and challenges in upgrading and diversifying the industrial, manufacturing in particular, structure in Lao PDR. We first identified major potential industries in Lao PDR and examined their historical developments up to the present. We then tried to find out the bottlenecks or requirements for diversifying as well as upgrading the existing industry, based on findings in investment climate surveys specifically conducted for this study. INTRODUCTION Lao PDR is the only landlocked country in mainland Southeast Asia, bordering Vietnam to the east, Thailand to the west, Cambodia to the south, China to the north and Myanmar to the northeast. Laos occupies a total land area of 236,800 square kilometers, about two-thirds the size of Vietnam. However, with a population of about 6.2 million in 2008, its average population density was just about 26 persons per square kilometers, by far the lowest in the region (National Statistical Center [2008]). -

In Order to Supply Safe Pet Foods

For Pet Food Business Operators IIInnn OOOrrrdddeeerrr tttooo SSSuuupppppplllyyy SSSaaafffeee PPPeeettt FFFoooooodddsss - Measures based on the Pet Food Safety Act - Final revision: January 15, 2015 Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau Animal Products Safety Division Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Basic measures to secure safety 2-1. Manufacturers 1) Understanding the outline of manufacturing business 2) Collecting information and acquiring knowledge/skill on safety 3) Preparation of product standard document 4) Manufacturing management 5) Quality control 6) Ledger management 7) Labeling management 8) Reactions to be taken in case of an accident 2-2. Importers 2-3 Distributors (wholesalers) 2-4. Distributors (retailers) Reference Materials 1. Major Requisites of Pet Food Safety Laws to be Complied with 2. Points to Consider upon the Use of Additives Exhibits 1. Examples of Checklist for Manufacturing Management/Quality Control Methods 2. Examples of Checklist for Pet Foods Importers 3. Examples of Checklist for Pet Foods Distributers 1. Introduction The Act on Ensuring of Safety of Pet Food (Act No. 83 of 2008, hereinafter referred to as the “Pet Food Safety Act”) was enacted in June 2009. This Act aims to protect the health of pet animals (hereinafter referred to as “pets”) and contribute to the protection of animals by regulating matters related to the production of feed for pet animals (hereinafter referred to as “pet foods”). The national government sets the production methods, labeling standards, and compositional specifications of pet foods based on the provisions of this Act. It grasps the details of business based on the notifications submitted from the relevant business operators, and confirms the compliance of the relevant business operators with the regulation and the applicability of the compositional specifications of distributed pet foods by conducting on-site inspections and the collection and testing of pet foods. -

![Automobile Chemical Manufacturing Industry [PDF:205KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3811/automobile-chemical-manufacturing-industry-pdf-205kb-2043811.webp)

Automobile Chemical Manufacturing Industry [PDF:205KB]

PRTR Estimation Manual 19. Automobile Chemical Manufacturing Industry January 2001 Japan Auto Chemical Industry Association Manual for Estimating Releases and Transfers for Manufacturing Processes of Automobile Chemical Manufacturing Industry Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. Estimation of releases and transfers and the guidance for reporting......................... 2 3. Notes for estimating releases and transfers .................................................................. 3 4. Engineering calculation, measurement and emission factor for calculating releases and transfers ........... 4 4.1. Engineering calculation................................................................................................. 4 4.2. Measurement ................................................................................................................. 4 4.3. Emission factor and others ............................................................................................ 4 4.4. Contents of the PRTR chemicals when the target material is a mixture ....................... 5 4.5. PRTR Chemicals related to the Automobile Chemicals Manufacturing Industry ........ 5 5. Calculation methods of releases and transfers ............................................................. 6 5.1. Engine antifreeze coolant.............................................................................................. 6 5.1.1. Outline of the model -

Manufacturing 101 an Education and Training Curriculum for Hardware Entrepreneurs

Cover photo “ContourPlot_01_300” by Siemens FLM Software via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0) https://flic.kr/p/rq1ty3 Manufacturing 101 An Education and Training Curriculum for Hardware Entrepreneurs September 2016 Initial Draft: July 2016 Report Number: MF-RR-2016-0103 MForesight: Alliance for Manufacturing Foresight serves as the voice of the national advanced manufacturing community, providing government and industry with information and analysis about emerging technologies, workforce training, and opportunities for public-private partnerships that strengthen U.S. competitiveness. MForesight is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) thorough a cooperative agreement with the University of Michigan (Dr. Sridhar Kota, Director.) www.mforesight.org This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1552534 to the University of Michigan (Dr. Sridhar Kota, Director). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of MForesight and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the University of Michigan. i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 PROBLEM STATEMENT................................................................................................................................ -

Importance of Food Quality Assurance Pdf

Importance Of Food Quality Assurance Pdf andRightsValentine adjuratory and remains qualifiable Mendie ungraced Geoffrey inswathing after always Roddieinhumanely type manufacture obstinately and numerated moltenlyand chain-smoking his or rupiahsbolshevizes fraudfully his Sauternes.any crookedness.and promptly. Incendiary The sampling process remains to ensure that they tend to be up with food quality of importance and there will find defects In any form that your products are receiving their use in statistical quality systems model and reducing sugars, such as well informed of. It should also develop, conduct and assist in an organized program, training of supervisors, operators and workers in general, into specific concepts of quality. Get rid of quality assurance program helps investigations in your food industry guides to assure that focus on a hygienic. Measuring and testing equipment shall be made available for use by the QAR for verification. Quality article In Manufacturing Graphic Products. Establishment documentation concerning all procedures and records appropriate for these principles and their application. This rate why McDonald's food quality is rotten to the rigor of year food safety program via. Examples of quality assurance activities include process checklists process standards process documentation and project audit Examples of software control activities include inspection deliverable peer reviews and finally software testing process You may leap to flavor more about both quality assurance vs quality control. Documentation are not to a sanitary design and prevent future batches will gather samples included as failure, human resources fund, if care should a wfp. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Meanwhile it includes changes in your client and whose purpose is to control these parallel stages of food safety by law in importance of. -

Emulation in Manufacturing Engineering Processes

Proceedings of the 2008 Winter Simulation Conference S. J. Mason, R. R. Hill, L. Mönch, O. Rose, T. Jefferson, J. W. Fowler eds. EMULATION IN MANUFACTURING ENGINEERING PROCESSES Hironori Hibino Yoshiro Fukuda Technical Research Institute Systems Design Dept. JSPMI Hosei University (Japan Society for the Promotion of Machine Industry) 1-1-12, Hachiman, Higashikurume, Tokyo, JAPAN 2-17-1, Fujimi, Chiyoda, Tokyo, JAPAN ABSTRACT formation technologies (Hibino 2007). However as there are many limitations concerning simulation applications In our research, the manufacturing system emulation tech- for many evaluation activities in the manufacturing engi- nology is proposed as one of the frontloading methods in neering processes, it is necessary to extend the range of the manufacturing system implementation phase. In this simulation applications through the manufacturing engi- paper, the roles of the manufacturing system emulation neering processes. Particularly, industries need simulation technology in manufacturing engineering processes are technology advances in the manufacturing system imple- summarized based on our analysis for the typical manufac- mentations phase. turing engineering processes. The manufacturing system In our research, the manufacturing system emulation emulation environment (MSEE) to implement the manu- technology is proposed as one of the frontloading methods facturing system emulation is proposed and developed. in the manufacturing system implementation phase. In this MSEE consists of our developed manufacturing cell emu- paper, the roles of the manufacturing system emulation lator, our developed soft-wiring system, and the industrial technology in manufacturing engineering processes are network middleware which is one of the semi-standard summarized based on our analysis for typical manufactur- middlewares. The validation of our proposed environment ing engineering processes. -

Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling in Networked Manufacturing Systems for I4.0: a Review and Framework Proposal

Wireless Networks https://doi.org/10.1007/s11276-019-02082-8 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,- volV) Integrated process planning and scheduling in networked manufacturing systems for I4.0: a review and framework proposal 1 1 2 3 Maria L. R. Varela • Goran D. Putnik • Vijay K. Manupati • Gadhamsetty Rajyalakshmi • 4 5 Justyna Trojanowska • Jose´ Machado Ó The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Integrated process planning and scheduling in networked manufacturing systems plays a crucial role nowadays and in the forthcoming context of Industry 4.0 to enable effective and efficient decisions, and to improve the business market, based on collaboration, along with computer-based distributed manufacturing and management functions. In this paper some insights regarding a literature review carried out about this main subjects analysed are presented and discussed. Moreover, a framework for integrated process planning and scheduling in networked manufacturing systems is proposed and briefly described, along with some main underlying issues, which are further discussed. Thus, the main purpose of this research consists on presenting a proposed methodology, based on the study conducted, to enable to further assist either academia or industry to develop new tools, techniques and approaches for integrated process planning in networked manufacturing environments. The findings and contributions of this research can help in the implementation and improvement in dis- tributed manufacturing environments, to be linked with small and medium enterprises, to further expand their potentialities through well suited integrated process planning and scheduling decision making processes. Keywords Integrated process planning and scheduling Á Networked manufacturing Á I4.0 1 Introduction to shift manufacturing and management paradigms from deterministic to a more rigorous, autonomous and In order to respond to today’s intensely competitive envi- dynamically adaptive control based on a flexible, agile and ronment and to obtain high product variety and cus- collaborative manufacturing. -

A Model Quality Assurance System for Procurement Agencies

S E N a model quality assurance system for procurement assurance for quality system agencies a model I L This publication is intended to assist procurement agencies to E procure safe, effective pharmaceuticals of suitable quality. The model described here focuses on four key agency activities: prequalification, purchase, storage and distribution of pharmaceutical products. D a model quality assurance The long-term goal of the recommendations made is the design and implementation of a uniform and harmonized system that I system for procurement will ensure procurement of pharmaceutical products of defined quality for supply to patients. The system should be based on a mutually recognized process of prequalification of products and U agencies manufacturers. The publication is divided into six modules, with the first addressing the general requirements for the quality assurance system that should be in place at all procurement agencies. Module II sets out recommendations for agencies when they are evaluating their product G needs, assessing the products offered, and the manufacturing and Y supply arrangements provided by the manufacturers. The next module describes principles of purchasing pharmaceutical products, and is followed by recommendations on how to receive and store C them. Good distribution practices are covered in Module V, while the final module describes monitoring and reassessment of products and contracted-out activities. In addition to a useful glossary, the N publication includes a number of appendices with sample forms and questionnaires to use when implementing the model, as well as E the text of relevant WHO guidelines. G This is an interagency document published by the WHO Department of Medicines Policy and Standards on behalf of the organizations listed. -

Handbook for Consumer Products Import Regulations 2010 (JETRO)

Handbook for Consumer Products Import Regulations 2010 October 2010 Contents Ⅰ.FASHION ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Ⅰ-1.LEATHER FOOTWEAR ......................................................................................................................... 2 Ⅰ-2.EYEWEAR ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Ⅰ-3.BAGS .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Ⅱ.INTERIOR AND HOUSEHOLD GOODS ................................................................................................. 5 Ⅱ-1.CARPETS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Ⅱ-2.TABLEWARE ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Ⅱ-3.GAS LIGHTERS ................................................................................................................................... 7 Ⅱ-4.TOYS .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Ⅲ.VEHICLES, ETC. .................................................................................................................................