Ethnic Awareness in Vikram Seth's 'A Suitable Boy'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 VIKRAM SETHAS a RECOGNIZED HUMANISM WRITER in 20 CENTURY in a SUITABLE BOY D. Dhamayanthi

International Journal of Engineering Research and Modern Education (IJERME) Impact Factor: 7.018, ISSN (Online): 2455 - 4200 (www.rdmodernresearch.com) Volume 3, Issue 1, 2018 VIKRAM SETHAS A RECOGNIZED HUMANISM WRITER IN 20th CENTURY IN A SUITABLE BOY D. Dhamayanthi Assistant Professor, Department of English, Shri Sakthikaiassh Women‟s College, Ammapet, Salem, Tamilnadu Cite This Article: D. Dhamayanthi, “Vikram Sethas A Recognized Humanism Writer in 20th Century in a Suitable Boy”, International Journal of Engineering Research and Modern Education, Volume 3, Issue 1, Page Number 1-3, 2018. Copy Right: © IJERME, 2018 (All Rights Reserved). This is an Open Access Article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract: Seth, a master of many genres at once is a poet, a travel writer, a novelist, and a writer of children‟s stories. He is perhaps the first Indian writer who is truly transnational. His novels provide a humanitarian worldview in the age of pop culture and global consumerism. A Suitable Boy is a true Indian novel in English. In its representation of linguistic inclusiveness, it reaffirms Nehru‟s secularism and nationalism. It elaborates the discourse of modernity in the third world, particularly in the manner in which this modernity is negotiated. It also addresses the contemporary problem of communal violence that has gripped India and the subcontinent in the post-independence period. Through a sub- plot in the text involving an inter-religious love story, it contextualizes the Indian political scene. As a result, the public and the private domains of the characters do not remain mutually exclusive categories. -

Vishwasroop 2

www.WeeklyVoice.com BOLLYWOOD Friday, June 15, 2018 | B-3 Janhvi, Ishaan Said To Sizzle In ‘Dhadak’ Enter to win MUMBAI: First things irst. Going Movie Passes by the trailer, Karan Johar’s produc- tion and Shashank Khaitans directori- al “Dhadak” is nothing like the original ilm “Sairat”. “Dhadak” is not an adaptation. It is a diferent beast altogether. Far more lamboyant and feral, illed with noise, colour and drama, leaving behind the comparatively compact world of “Sairat” where the stress was on the friction between the two castes which clashed over the lovers’ auda- cious crossover from into each other’s forbidden territory. This is a more generic world of co- lour, drama and music undercut by an overweening innocence and a ru- inous oblivion to the ground reality der to the passion of irst-love look Manjule would ind it hard to recog- that makes the lovers look as pristine convincing, sincere and heartfelt even nise his own ilm in this hybrid avatar as Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia in today’s age of unrelieved cynicism. of colours and emotions that leap at Which was the irst in “Bobby”. In Janhvi, we see heartstopping us with enticing fervour. Indeed, Ishaan Khatter and Janhvi lashes of her legendary mother But there is one proud mother up ilm directed by Kapoor bring into play the same non- Sridevi, specially in the way she proj- there smiling every time her daughter sexual dynamics of intense love that ects the arrogant proprietary pride of smiles on-screen. A star is reborn. maestro Subhash Ghai? William Shakespeare and then Raj ownership every time she looks at her Director Shashank Khaitan and pro- Kapoor mastered in their versions of utterly smitten other. -

Global Heart Transplant’

THURSDAY 16 NOVEMBER 2017 LIFESTYLE | 7 BOLLYWOOD | 11 The invisible Janhvi Kapoor & donor of Ishaan Khatter ‘global heart to be launched transplant’ in KJo’s film Before the 20th century, Qatar’s economy was primarily characterised by fish- ing and pearling. However, the discovery of oil reserves in the 1940s has led to its development into one of the biggest multifaceted economies in the world. The state has experienced such a rapid economic growth that has transformed its physical, social, cultural and demographic status. A JOURNEY TO QATAR’S DEVELOPMENT P | 4-5 03 THURSDAY 16 NOVEMBER 2017 CAMPUS WCM-Q student and alumnus team up for medical research he research of a first-year of Assisted Reproduction and important health issue for our medical student at Weill Cor- Genetics is an official publication region.” Tnell Medicine-Qatar (WCM-Q) of the American Society of Repro- Aya’s research at Weill Cornell has been published in a leading sci- ductive Medicine. Medicine in New York was sup- entific journal, thanks to the Aya said: “I am very happy to ported by the Medical Student mentorship of a WCM-Q graduate see my research published and Research Award, an initiative that who is now on the faculty at Weill extremely grateful to Dr. Nigel facilitates research experiences for Cornell Medicine in New York. Pereira for being such a proactive students who demonstrate an apti- Aya Tabbalat’s research project and encouraging mentor. His guid- tude for scientific enquiry. on the fertility of women in the Ara- ance, knowledge and passion for Dr. -

Reproductiverights.Org…

LITIGATING REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS: Using Public Interest Litigation and International Law to Promote Gender Justice in India Center for Reproductive Rights 120 Wall Street New York, New York 10005 www.reproductiverights.org [email protected] Avani Mehta Sood Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow Yale Law School [email protected] © 2006 Center for Reproductive Rights Avani Mehta Sood Any part of this report may be copied, translated, or adapted with permission of the Center for Reproductive Rights or Avani Mehta Sood, provided that the parts copied are distributed free or at cost (not for profit), that they are identified as having appeared originally in a Cen- ter for Reproductive Rights publication, and that Avani Mehta Sood is acknowledged as the author. Any commercial reproduction requires prior written permission from the Center for Reproductive Rights or Avani Mehta Sood. The Center for Reproductive Rights and Avani Mehta Sood would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. ISBN: 1-890671-34-7 978-1-890671-34-1 page 2 Litigating Reproductive Rights About this Report This publication was authored by Avani Mehta Sood, J.D., as a Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow working in collaboration with the Center for Reproductive Rights. The Robert L. Bernstein Fellowship in International Human Rights is administered by the Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School. In 2004, the Center for Reproductive Rights launched a global litigation campaign to promote the use of strategic litigation for the advancement of women’s reproductive rights worldwide. -

A Suitable Boy Vikram Seth Reviewed By: Keertana Sripathi, 15 Star Teen

A Suitable Boy Vikram Seth Reviewed by: Keertana Sripathi, 15 Star Teen Book Reviewer of Be the Star You Are! Charity www.bethestaryouare.org A Suitable Boy is an Indian fiction novel by Vikram Seth. This novel is a love story set a few years after India’s independence from the British and India’s partition, leading to India and Pakistan as neighboring countries. The heroine and protagonist of the story is Lata Mehra, who is a young woman studying literature in Brahmpur. The novel starts with the wedding of Lata’s elder sister Savita and Pran Kapoor. During the wedding, Lata’s widowed mother Mrs. Rupa Mehra tells Lata strictly that she will marry a man only of her choice. The novel is about whom Lata will marry, the man she loves irrationally or the man of her mother’s choice who is the most practical choice for Lata. A Suitable Boy is written in an omniscient point of view, allowing the reader to understand what is going on from many characters’ perspectives. Although this story is mainly a love story, politics and religion are also written about a lot. Lata has three siblings who are the easily raged Arun who partially takes the role of his father after his death and is married to the cold but glamourous Meenakshi, the soft-spoken and sweet Savita happily married to Pran Kapoor who is the son of the former Minister of Revenue, and Varun who is fond of horse races but very much dominated by his elder brother Arun. Lata does not think much about marriage but as the story progresses, she starts to understand its beauty and purpose. -

The Invention of India in Vikram Seth's a Suitable

> Research & Reports The Invention of India in Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy With his representation of India in the 1950s, Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1993) has seems to be ‘saying everything about Research > appropriated the nineteenth-century realist tradition in novel writing to his own ends. The India’, while in fact its vast descriptive South Asia Nehruvian idea of India as a ‘unity within diversity’ and a secular approach to religion horizon is not infinite, and is shaped by features prominently in this novel. Its vast descriptive horizon is contained within a the discourse of the narrator. Realist deceptively styleless language, naturalizing what is in fact a carefully constructed ‘imagined description is characterized by the community’. interweaving of the aesthetic and ref- erential purposes. The aesthetic pur- By Neelam Srivastava state assumed full responsibility for the the development of the novel: the main pose has a containing function, in that marginalized groups that had not been narrative events, the dialogues, the it directs the description towards the Suitable Boy provides a synchron- prime beneficiaries of the transition thoughts of the characters, and the production of a meaning. On the other Aic look at post-Independence Indi- from colonialism to independence. Cer- direct authorial interventions. There are hand, the assumed reality of the refer- an life of the 1950s, in many ways a tain cultural products, such as Indian some privileged moments where Seth’s ent prevents the description to turn into tranche de vie. It aspires to provide an nationalist novels, ‘endorsed and construction of his discourse emerges fantasizing. -

PORTRAYAL of INDIA of the 1950S in MIRA NAIR's MINISERIES a SUITABLE

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.9.Issue 2. 2021 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (April-June) Email:[email protected]; ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE PORTRAYAL OF INDIA OF THE 1950s IN MIRA NAIR’S MINISERIES A SUITABLE BOY VEENA SINDHU1, Dr. ARCHANA HOODA2 1Assistant Professor of English, Govt. College for Girls, Sector-14, Gurugram (Haryana) Email address- [email protected] 2Associate Professor of English, Govt. College for Girls, Sector-14, Gurugram (Haryana) Email address- [email protected] Abstract Vikram Seth’s 1474 page novel A Suitable Boy written in 1993 was adapted by Andrew Davies into a six episode serial and was directed by Mira Nair. This BBC television drama released on 23 Oct 2020 on Netflix depicts the social, economic, political and cultural upheaval of newly independent India of 1950s. The serial covers the events, the issues and challenges encountered in the time span of one Article Received: 28/05/2021 year from 1950 to 1951 in the post independent era. Though on the surface the Article Accepted: 26/06/2021 Published online:30/06/2021 story appears to be of a mother’s aspiration to find a suitable match for her daughter DOI: 10.33329/rjelal.9.2.322 and the daughter torn between her duty towards her mother and her instinct to follow her heart’s desire, the serial actually holds a mirror to society. The diversity of characters in the serial represents the various facets of being an Indian in the early 1950s. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

Indian Council of Arbitration List of Panel of Arbitrators - As on October 23, 2010)

(Judges) INDIAN COUNCIL OF ARBITRATION LIST OF PANEL OF ARBITRATORS - AS ON OCTOBER 23, 2010) 1 Membership No: IL/ICA/0735 2 Mr. Justice Mam Chandra Agarwal Membership No: IL/ICA/0766 Former Judge Allahabad High Court, Mr. Justice P C Agarwal Flat No. 1133, Sector-29, Former Judge, High Court of M.P., Noida-201303 A189, First Floor, Sector-20 (Near Kotwali) Phone: 0120-2453952/0981554142 /Email: Noida-201301 Date of Birth 02/09/1938 (Age: 71) Phone: 9818327680, 95120-2548442 /Email: Particulars: Retd. Judge, Allahabad High Court. Sessions Judge, Addl. Distt. Date of Birth 1/6/1943 (Age: 66) &Sessions Judge and Judicial Member, Income Tax Appellate Tribunal. Particulars: Retd. Judge, High Court of Madhya of India. 3 4 Membership No: IL/ICA/0767 Membership No: IL/ICA/0802 Mr. Justice S K Agarwal Ms. Justice Sharda Aggarwal Former Judge High Court of Delhi Former Judge Delhi High Court A-62, Nizamuddin (East) B-126, Sarvodya Enclave New Delhi-110013 New Delhi-110017 Phone: 24656722 /Email: Phone: 26516186/9818032419 /Email: [email protected] Date of Birth 4/4/1944 (Age: 65) Date of Birth 12/1/1940 (Age: 69) Particulars: Former Judge, High Court of Delhi. Particulars: Retd. Judge, Delhi High Court. Ministry of Labour. 5 6 Membership No: IL/ICA/0805 Membership No: IL/ICA/0841 Mr. Justice V S Aggarwal Mr. Justice A S Aguiar Former Judge High Court Former Judge Bombay High Court C-52, Swami Nagar Benalin Home 122 Kalina New Delhi-110017 Santa Cruz (East) Phone: 26491797 /Email: Mumbai-400029 Date of Birth 8/28/1940 (Age: 69) Phone: 26661963 /Email: Particulars: Retd. -

NMMC Starts Second Phase of Covid 19 Vaccination

The Dynamic Daily Newspaper of Navi Mumbai Friday, 5 February 2021 www.newsband.in Pages 8 • Price 2 VOL. 14 • ISSUE 203 RNI No. MAHEN/2007/21778 POSTAL REGN. No. NMB/154/2020-22/VASHI MDG POST OFFICE Maharashtra Colleges NMMC starts second and Universities to open Things to do to from 15th February manage your phase of Covid 19 By Ashok Dhamija cancer-related pain: aharashtra State Dr Uma Dangi MHigher and Tech- On the occasion nical Education Min- of World Cancer Day vaccination ister, Uday Samant, on 2021, Dr. Uma Dangi, 195 people vaccinated against Covid-19 on Wednesday announced Oncologist at Hiranan- the opening of the State dani Hospital, Vashi the first day of the second phase Colleges and Universi- shares her valuable ties from Monday 15th views for the benefit he Navi cinated in this February, 2021. The of Newsband readers TMum- phase. The vac- same will, however, how to deal with Can- bai Municipal cination is being commence with 50 per- Minister for Higher and Tech- cer-related pain that C o r p o r a t i o n administered at cent of the total capac- nical Education, Maharash- can be very taxing on (NMMC) has Apollo Hospital, ity, as of now, on rota- tra, Uday Samant the mind and body... started the sec- Belapur, Reli- tional basis in complete (More on page 7) ond phase of the ance Hospital, compliance with the state, which have been Covid 19 vac- Khairane MIDC COVID-19 protocols. shut since March 2020 Banned gutkha cination drive and NMMC T h e seized by police from 4th Feb- civic Hospital, same comes Airoli. -

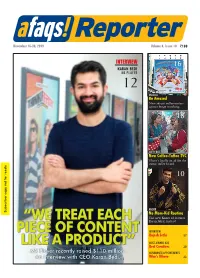

Rajesh Sethi 17 LIKE a PRODUCT” MOST-VIEWED ADS Best Creatives 20 MX Player Recently Raised $110 Million

November 16-30, 2019 Volume 8, Issue 10 `100 INTERVIEW 16 KARAN BEDI MX PLAYER 12 IMAGICA Be Amazed New ads pit rollercoasters against binge watching. 18 COFFY BITE New Coffee-Toffee TVC There’s finally an ad for the iconic toffee brand. 10 KNORR Subs riber o yf not or resale No Mom-Kid Routine The new Knorr ad features “WE TREAT EACH Karan Johar, instead. PIECE OF CONTENT INTERVIEW Rajesh Sethi 17 LIKE A PRODUCT” MOST-VIEWED ADS Best Creatives 20 MX Player recently raised $110 million. MOVEMENTS/APPOINTMENTS An interview with CEO Karan Bedi. Who’s Where 22 EDITORIAL This fortnight... Volume 8, Issue 10 EDITOR Sreekant Khandekar hough relatively new in the larger scheme of entertainment, algorithm based PUBLISHER November 16-30, 2019 Volume 8, Issue 10 `100 T content consumption has been around long enough for ‘pro’ and ‘against’ Sreekant Khandekar INTERVIEW 16 KARAN BEDI camps to have developed. The latter, which I belong to, is based on a simple premise EXECUTIVE EDITOR MX PLAYER 12 – if recommendation engines keep pushing content of the kind we’ve already Ashwini Gangal IMAGICA Be Amazed PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE New ads pit rollercoasters watched, how will we ever discover new, contrarian types of content? Where’s the against binge watching. Andrias Kisku 18 serendipity and human folly in a world in which humans have less volition than a ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES platform? I’ve disabled YouTube’s auto-play option, in a bid to take back some of Shubham Garg COFFY BITE New Coffee-Toffee TVC the agency I feel a sense of having lost to it. -

December 17Th, 2018 Legal Current Affairs Questions

December 2018 Legal Current Affairs for Law Entrance Exam DEC LEGAL CA QUIZ 17 Directions: Study the following questions carefully and answer the questions given below. 1. Belgium has recently defeated which of following countries to win FIH Hockey World Cup 2018? A. Netherlands B. France C. Canada D. India E. None of these 2. Ramphal Pawar was recently appointed as the Director of _______________ . A. Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems B. National Crime Record Bureau C. Bureau of Police Research and Development D. Central Bureau of Investigation E. None of these 3. Who among the following has recently been appointed as Prime Minister of which of the following countries? A. Bangladesh B. Sri Lanka C. Nepal D. Tibet E. None of these 4. Catriona Gray was recently crowned Miss Universe 2018. She is from which of the following countries? A. Philippines B. USA C. Canada D. Russia E. None of these 5. India has recently announces $1.4 billion package for which of the following countries? A. Vietnam B. Maldives C. Bangladesh D. Nepal E. None of these 6. Anders Samuelsen was on a visit to India, recently. He is Foreign Affairs Minister of which of the following countries? A. Denmark B. Greenland C. Finland D. Norway E. None of these 7. Which of the following countries has recently set record in Nuclear Power Operation? A. China B. Pakistan C. India D. Russia E. None of these 8. Which of the following countries has recently hosted UN Climate Conference 2018? A. Greenland B. Ireland C. Poland D.