Siuslaw National Forest FY 2013 Monitoring Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Oregon Administrative Rules Compilation

2019 OREGON ADMINISTRATIVE RULES COMPILATION CHAPTER 736 Parks and Recreation Department Published By DENNIS RICHARDSON Secretary of State Copyright 2019 Office of the Secretary of State Rules effective as of January 01, 2019 DIVISION 1 PROCEDURAL RULES 736-001-0000 Notice of Proposed Rules 736-001-0005 Model Rules of Procedure 736-001-0030 Fees for Public Records DIVISION 2 ADMINISTRATIVE ACTIVITIES 736-002-0010 State Park Cooperating Associations 736-002-0015 Working with Donor Organizations 736-002-0020 Criminal Records Checks 736-002-0030 Definitions 736-002-0038 Designated Positions: Authorized Designee and Contact Person 736-002-0042 Criminal Records Check Process 736-002-0050 Preliminary Fitness Determination. 736-002-0052 Hiring or Appointing on a Preliminary Basis 736-002-0058 Final Fitness Determination 736-002-0070 Crimes Considered 736-002-0102 Appealing a Fitness Determination 736-002-0150 Recordkeeping, Confidentiality, and Retention 736-002-0160 Fees DIVISION 3 WILLAMETTE RIVER GREENWAY PLAN 736-003-0005 Willamette River Greenway Plan DIVISION 4 DISTRIBUTION OF ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLE FUNDSTO PUBLIC AND PRIVATELY OWNED LANDMANAGERS, ATV CLUBS AND ORGANIZATIONS 736-004-0005 Purpose of Rule 736-004-0010 Statutory Authority 736-004-0015 Definitions 736-004-0020 ATV Grant Program: Apportionment of Monies 736-004-0025 Grant Application Eligibility and Requirements 736-004-0030 Project Administration 736-004-0035 Establishment of the ATV Advisory Committee 736-004-0045 ATV Operating Permit Agent Application and Privileges 736-004-0060 -

Botany, Invasive Plants, Native Plants, Genetics

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest FY-16 Region Program Accomplishments Calochortus umpquaensis, Umpqua mariposa lily, is found only in the Umpqua River watershed of Botany southwestern OR. A big "anthophorid" bee is tucked into the flower. Invasive Plants Native Plants Genetics U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Media Release | Spring 2020 | Bandon Oregon Chamber of Commerce

MEDIA RELEASE | SPRING 2020 | BANDON OREGON CHAMBER OF COMMERCE BIRD’S EYE VIEW A SHOP WITH A VIEW Birds are among the most fascinating With Oregon grown (or caught, or made) wildlife species on the Southern products offered year round, Farm & Sea is a Oregon Coast. And species diversity sets Bandon apart as a birdwatching specialty food store for shoppers with a West destination. Outdoors p. 1 Coast palate. Dining p. 3 SHINE A LIGHT ON HISTORY NATURE’S WONDERS Built to stand the test of time, Oregon Coast Connect with Bandon’s natural wonder! lighthouses are among the region’s most Professional guides share their passion for nature on guided exploration of iconic architectural attractions. Make a day of trails and waterways. Outdoors p. 2 it– or two– and visit all four Southern Oregon Coast lighthouses. History & Culture p. 4 March 2020 Release To our friends in the media, including publishers, editors, writers and photographers– Thank you for your interest in Bandon and the Southern Oregon Coast! We are excited to highlight unique and timely tourism and recreation opportunities in 2020, including new business partners and the 150th anniversary of the lighthouse at Cape Blanco. The timing of this media release packet coincides with protective measures to slow the spread of COVID-19. Many of our area businesses have temporarily adjusted services or changed business hours, events have been cancelled or postponed, and many public venues are closed or have delayed seasonal opening. When you’re ready to visit or follow up on a story, please contact us. We’re here to help with your travel and research. -

A Bill to Designate Certain National Forest System Lands in the State of Oregon for Inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for Other Purposes

97 H.R.7340 Title: A bill to designate certain National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for other purposes. Sponsor: Rep Weaver, James H. [OR-4] (introduced 12/1/1982) Cosponsors (2) Latest Major Action: 12/15/1982 Failed of passage/not agreed to in House. Status: Failed to Receive 2/3's Vote to Suspend and Pass by Yea-Nay Vote: 247 - 141 (Record Vote No: 454). SUMMARY AS OF: 12/9/1982--Reported to House amended, Part I. (There is 1 other summary) (Reported to House from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs with amendment, H.Rept. 97-951 (Part I)) Oregon Wilderness Act of 1982 - Designates as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System the following lands in the State of Oregon: (1) the Columbia Gorge Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (2) the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (3) the Badger Creek Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (4) the Hidden Wilderness in the Mount Hood and Willamette National Forests; (5) the Middle Santiam Wilderness in the Willamette National Forest; (6) the Rock Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (7) the Cummins Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (8) the Boulder Creek Wilderness in the Umpqua National Forest; (9) the Rogue-Umpqua Divide Wilderness in the Umpqua and Rogue River National Forests; (10) the Grassy Knob Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou National Forest; (11) the Red Buttes Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou -

Oregon Scorp & State Park Planning

OREGON SCORP & STATE PARK PLANNING An Innovative Research Collaboration between Oregon State Parks and Oregon State University OREGON SCORP AND STATE PARK PLANNING Collaborative Planning Projects . State Park Survey Project & Economic Impact Analysis . SCORP In-State Outdoor Recreation Survey . In-State Trail User Survey OREGON SCORP AND STATE PARK PLANNING Early Visitor Survey Project Work . In 2009, OPRD worked with a university research team to develop an ongoing visitor survey project. Project purpose to improve understanding of visitors to better provide appropriate facilities, programs and services which they desire. Proposal included 5 day-use and 5 overnight parks per year for 4 years (450 completions per park). Total cost of $304,000 ($76,000 per year) or $7,600 per park report. Not a sustainable model. OREGON SCORP AND STATE PARK PLANNING 2010 Champoeg Pilot Test Background: . In the summer of 2010, OSU conducted a visitor survey at Champoeg State Heritage Area . Purpose was to test multiple survey approaches to inform future survey efforts for the entire state park system. Compared survey modes (onsite, internet, mail, phone) . Recommendations included final survey instruments & survey methods OREGON SCORP AND STATE PARK PLANNING Methodology Day Users . Onsite full survey (volunteers/ Camp Hosts) . Onsite short survey (contacts for full surveys) . Telephone full survey (Reservations NW) . Mail full survey (OSU) . Internet full survey (OSU) Overnight Users . Contacts from reservation system information . Telephone full survey (Reservations NW) . Mail full survey (OSU) . Internet full survey (OSU) Methodology Completed surveys (n) Response rate (%) Day Users Onsite 251 71 Mail 156 55 Internet 104 40 Telephone 56 29 Subtotal 567 52 Overnight Users Mail 298 60 Internet 265 52 Telephone 176 29 Subtotal 739 45 Total 1,306 47 OREGON SCORP AND STATE PARK PLANNING 2010 Champoeg Pilot Test Recommendations: . -

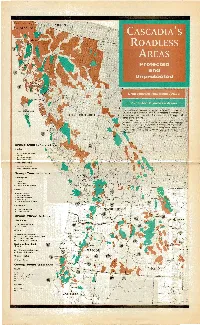

THE Easrsrne Group

Group One: THE NORTHERN IU Alaska ~ <, 1 Port Houghton-Cape Fanshaw 2 East Kuiu 3 Cleveland Peninsula 4 Upper Tenakee Inlet British Columbia 5 Great Bear Rainforest 6 Randy Stoltmann Wilderness Group Two: THE OwL REGION Washington 7 Pompey 8 Paradise Creek 9 Little Huckleberry Mountain Oregon 10 Salmon-Huckleberry 11 Hardesty Mountain 12 Smith-Umpqua Divide 13 Mount Bailey 14 Copper /North Fork Elk River California 15 Dillon Creek/Siskiyou 16 Orleans Mountain Group Three: THE EAsrsrnE Washington 17 Long Draw/Long Swamp 18 Devil's Gulch Oregon 19 Aldrich Mountain/Dry Cabin 20 North Fork John Day/Elkhorn/Greenhorn 21 Sky Lakes/Pelican Butte 22 Deadhorse Rim/Coleman Rim Northern Great Basin Oregon 23 High Steens/Little Blitzen Gorge 24 Trout Creek Mountains Oregon-Idaho 25 Owyhee Canyon Group Four: NORTHERN RocK1Es Idaho 26 Deadwood 27 French Creek/Patrick Butte 28 North Lochsa Slope 29 Cove-Mallard 30 Mount Jefferson Montana 31 Great Burn 32 Ninemile Valley ROADLESS AREAS AT RISK A Ca~cadia Sampler project, which would have built 93 miles of chum salmon. Goose Flats River, on the inlet's What's at stake: The Stoltmann har• road and cut 123 million board feet of timber south side, harbors brown bear, mink, marten bors the southern limit of North America's from the area, was withdrawn as the result of and Sitka black-tailed deer and draws large coas ta I grizzly bear population. a lawsuit. A new draft EIS is in the early plan• numbers of migrating waterfowl. Beautiful Status: Only 20 percent of this wilderness is ning stages. -

OR Wild -Backmatter V2

208 OREGON WILD Afterword JIM CALLAHAN One final paragraph of advice: do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast.... a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of your- selves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it is still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for awhile and contemplate the precious still- ness, the lovely mysterious and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive and I promise you this much: I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men with their hearts in a safe-deposit box and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this: you will outlive the bastards. —Edward Abbey1 Edward Abbey. Ed, take it from another Ed, not only can wilderness lovers outlive wilderness opponents, we can also defeat them. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men (sic) UNIVERSITY, SHREVEPORT UNIVERSITY, to do nothing. MES SMITH NOEL COLLECTION, NOEL SMITH MES NOEL COLLECTION, MEMORIAL LIBRARY, LOUISIANA STATE LOUISIANA LIBRARY, MEMORIAL —Edmund Burke2 JA Edmund Burke. 1 Van matre, Steve and Bill Weiler. -

Pacific Lamprey 2020 Regional Implementation Plan Oregon Coast

Pacific Lamprey 2020 Regional Implementation Plan for the Oregon Coast Regional Management Unit South Coast Sub-Region Submitted to the Conservation Team August 12, 2020 Primary Authors Primary Editors J. Poirier U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service K. Coates Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians This page left intentionally blank Status and Distribution of Pacific Lamprey in the RMU General Description of the RMU South Oregon Coast Sub-Region The Oregon Coast Regional Management Unit is separated into two sub-regions equivalent to the USGS hydrologic unit accounting units 171002 (Northern Oregon Coastal) and 171003 (Southern Oregon Coastal). The South Oregon Coast sub-region includes all rivers that drain into the Pacific Ocean from the Umpqua River basin south to the Smith River boundary in California. It is comprised of twelve 4th field HUCs ranging in size from 1,216 to 4,662 km2 (Table 1). Watersheds within the South Oregon Coast sub-region include the North and South Umpqua, Umpqua, Coos, Coquille, Sixes, Upper, Middle and Lower Rogue, Applegate, Illinois and Chetco (Figure 1). Figure 1. Map of watersheds within the Oregon Coast RMU, South Coast sub-region. South Coast sub-region - RIP Oregon Coast RMU August 12, 2020 1 Table 1. Drainage Size and Level III Ecoregions of the 4th Field Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) Watersheds located within the South Oregon Coast sub-region. Watershed HUC Number Drainage Size (km2) Level III Ecoregion(s) North Umpqua 17100301 3,544 Cascades, Klamath Mountains South Umpqua 17100302 4,662 Coast Range, Cascades, -

Public Law 98-328-June 26, 1984

98 STAT. 272 PUBLIC LAW 98-328-JUNE 26, 1984 Public Law 98-328 98th Congress An Act June 26, 1984 To designate certain national forest system and other lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, and for other purposes. [H.R. 1149] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Oregon United States ofAmerica in Congress assembled, That this Act may Wilderness Act be referred to as the "Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984". of 1984. National SEc. 2. (a) The Congress finds that- Wilderness (1) many areas of undeveloped National Forest System land in Preservation the State of Oregon possess outstanding natural characteristics System. which give them high value as wilderness and will, if properly National Forest preserved, contribute as an enduring resource of wilderness for System. the ben~fit of the American people; (2) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation (RARE II) of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have identified areas which, on the basis of their landform, ecosystem, associated wildlife, and location, will help to fulfill the National Forest System's share of a quality National Wilderness Preservation System; and (3) the Department of Agriculture's second roadless area review and evaluation of National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon and the related congressional review of such lands have also identified areas which do not possess outstand ing wilderness attributes or which possess outstanding energy, mineral, timber, grazing, dispersed recreation and other values and which should not now be designated as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System but should be avail able for nonwilderness multiple uses under the land manage ment planning process and other applicable laws. -

2016 Oregon Big Game Hunting Outlook Conditions for Big Game and Hunters Are Looking Much Better Than They Were a Year Ago

2016 Oregon Big Game Hunting Outlook Conditions for big game and hunters are looking much better than they were a year ago. Back in August of last year, 100 percent of Oregon was in severe drought and 50 percent in the even worse category of “extreme drought.” While parts of NE and SE Oregon are still experiencing a severe drought, conditions have improved across the state. “We had normal winter precipitation and a wet spring,” says Autumn Larkins, ODFW Assistant District Wildlife Biologist for Harney County. “Water availability is much better this year.” It’s a similar story in northeast Oregon. “The weather is much better suited to deer and elk production as opposed to last year’s record drought,” said Mark Kirsch, ODFW District Wildlife Biologist in Umatilla County. The increased water also better distribute animals during hunting season, rather than cluster them around fewer water sources. It should help distribute early season hunters, too— especially those pronghorn and bowhunters who crowded around the few water holes to set hunting blinds in recent years. The conflict between hunters over blind placement has gotten so bad that ODFW and BLM recently put together a flyer reminding hunters of the rules and good etiquette Now wildlife biologists are crossing their fingers for rains in September. These early fall rains green up forage and help big game put on weight, so animals head into breeding season in good body condition and fit to reproduce. Despite the increased moisture, fire is still a threat throughout Oregon. Most forestlands will have restrictions (such as no campfires) during fire season, and some private lands will be closed to public access entirely. -

Stewardship in the Siuslaw National Forest Whole Watershed Restoration for Ecological and Economic Benefit

Stewardship in the Siuslaw National Forest Whole watershed restoration for ecological and economic benefit The end result of stewardship and restoration in the Siuslaw National Forest is healthy forests and restored fish and wildlife habitat. History of Stewardship on the Siuslaw What is Stewardship Contracting? Home to Oregon’s fastest growing trees and threatened Stewardship contracting began in the Siuslaw in 2001 as a salmon, spotted owls and marbled murrelets, the Siuslaw “pilot project” for new federal authorities. In 2003, Congress National Forest on the Oregon coast saw some of the most authorized stewardship contracting for 10 more years. bitter battles over old-growth logging in the Pacific North- west twenty years ago. Stewardship contracting is a suite of authorities and con- tracting tools that are intended Action needed After the Northwest Forest Plan went into effect in 1994, to help the Forest Service and forest planners were required to preserve more old-growth Bureau of Land Management The success of 10 years of and riparian habitat for wildlife. Managers at the Siuslaw meet both land management stewardship contracting in National Forest saw an opportunity to advance forest stew- objectives and rural community the Siuslaw highlights the ardship and meet restoration, conservation and economic needs. The blending of these importance of gaining per- goals through new “Stewardship Authorities.” This provided objectives makes stewardship manent authorization from an opening to pursue a new type of management and to work contracting -

The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway by IRA A

VOLUMB 2 NUMBBI3 NOVBMBBR, 1916 . THE .MINERAL · RESOURCES OF OREGON ' PuLhaLed Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Mitchell Point tunnel and viaduct, Columbia River Hi~hway The .. Asenstrasse'' of America The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations Entered aa oeoond cl,... matter at Corvallis, Ore., on Feb. 10, l9lt, accordintt to tbe Act or Auc. :U, 1912. .,.,._ ;t ' OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION On1cm or THm Co><M188ION AND ExmBIT OREGON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Orncm or TBm DtBIICTOR CORVALLIS, OREGON .,~ 1 AMDJ WITHY COMBE, Governor HENDY M. PABKB, Director C OMMISSION ABTBUB M. SWARTLEY, Mining Engineer H. N. LAWRill:, Port.land IRA A. WILLIAMS, Geologist W. C. FELLOWS, Sumpter 1. F . REDDY, Grants Pass 1. L. WooD. Albany R. M. BIITT8, Cornucopia P. L. CAI<PBELL, Eugene W 1. KEBR. Corvallis ........ Volume 2 Number 3 ~f. November Issue {...j .· -~ of the MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published by The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology ~•, ;: · CONTAINING The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History l Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway t. By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations 1916 ILLUSTRATIONS Mitchell Point t unnel and v iaduct Beacon Rock from Columbia River (photo by Gifford & Prentiss) front cover Highway .. 72 Geologic map of Columbia river gorge. 3 Beacon Rock, near view . ....... 73 East P ortland and Mt. Hood . 1 3 Mt. Hamilton and Table mountain .. 75 Inclined volcanic ejecta, Mt. Tabor. 19 Eagle creek tuff-conglomerate west of Lava cliff along Sandy river.