Reconstructing Alfie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Irish Theme in the Writings of Bill Naughton by David Pierce York St John College

Estudios Irlandeses, Number 0, 2005, pp. 102-116 _______________________________________________________________________________ AEDEI The Irish Theme in the Writings of Bill Naughton By David Pierce York St John College _____________________________________________________________________ Copyright (c) 2005 by David Pierce. This text may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the notification of the journal and consent of the author. __________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: The student interested in cultural assimilation, hybridity, and naturalization, in masculinity, authorship, and identity, in what happened to the Irish in Britain in the twentieth century, will turn at some point to the Mayo-born, Lancashire writer Bill Naughton (1910-1992), author of a classic children’s story collection The Goalkeeper’s Revenge and Other Stories (1961), of Alfie (1965), the film which helped define 1960s London, and of a series of autobiographies largely centering on his Irish childhood and upbringing in Bolton. It has been the historic role of Irish writers from Richard Brinsley Sheridan to Oscar Wilde, from Elizabeth Bowen to William Trevor, to give the English back to themselves in a gallery of portraits. Naughton is part of this tradition, but, unlike these other writers, his subject is the English working class, which he writes about from within, with both sympathy and knowledge. It can be readily conceded that his work is not at the forefront of modern English or Irish writing, but it does deserve to be better known and appreciated. -

Entertainment

THURSDAY, NOV. 3, IH8 THE GEORGIA STATE SIGNAL BILLDIAL ENTERTAINMENT 'Alfie,' 'Seconds' Share Qualities Of Writing, Acting and Directing ~~ftlqoql "Alfie" and "Seconds" may "ALFIE" WAS directed by by Alfie and later submits to a seem to be strange bedfellows Lewis Gilbert, and his style is repulsive and degrading abor- Mf)VIES - RECORDS - BOOKS for a comparative review. "Al- more traditional. At least his tion. fie" is a British comedy about technique of photographing the We return, after considera- a lovable rogue who moves action of the film is less ob- tion of the various qualities of casually from one "bird" to the viously experimental than these films and of.their super- next 'with never, or hardly Frankenheimer's. For the most ficial differences, to the in- Sound Tracks Sound Good ever, a thought about tomor- part, the viewer is unaware of herent similarities in theme row. the film-making process itself, which tie them together. To Record Makers, Buyers "Seconds" is an American which is exactly what Gilbert THE ALL too obvious point horror movie a middle-aged by ED SIIEAIIAN intended. of "Seconds," and the irony of banker, bored with his subur- "Lara's Theme' - was it before you saw "Dr. Zhivago that What is most important to the title derives from this you realized that was quite a song? I'll bet you can't even re- ban life and his suburban wife, him is what should be most im- point, is that there are no 'sec- who submits to plastic surgery member now. It may have been the day after! portant to -his audience: Alfie's onds." The painful experiences which cuts 15 years from his That's the way with a good REED LINES: Mr. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Robert Lennard Collection

ROBERT LENNARD COLLECTION Extent - 20A Accessioned - May 2002 INTRODUCTION Born Walter Robert Lennard, 16 May 1912. 1929 - 1939 Assistant Casting Director at British International Pictures, Elstree Studios. 1939-1945 War duty in the National Fire Service [also working on a part-time basis for ABPC]. 1945 - 1955 Casting Director, Associated British Picture Corporation, Elstree Studios. Lennard was also sub-let during this time as casting director to Warner Bros European productions. 1955 - 1970 Chief Casting Director, Associated British Picture Corporation [also cast all Warner Bros European projects, mainly Fred Zinnemann productions, including THE NUN'S STORY (US,1958) , A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS (GB,1966) and unrealised project MAN'S FATE (c.1969)]. Lennard also worked closely with John Huston, casting all the director's European films, including MOBY DICK (GB,1956), FREUD (US, 1962) and THE KREMLIN LETTER (US, 1969). ARRANGEMENT OF MATERIAL The material is arranged as follows: WRL/1 – WRL/58 Realised Film Projects. WRL/59 Realised Television Projects. WRL/60 – WRL/62 Unrealised Film & Television Projects [mainly MAN'S FATE (c.1969)] WRL/63 General - Including correspondence, miscellaneous items and bound folders of British film cast lists arranged alphabetically by year. WRL/64 General/Personal 1 ROBERT LENNARD COLLECTION RADIO PARADE (GB, 1933) WRL/1/1 Typewritten list of cast and contracted rates of pay, nd. The OLD CURIOSITY SHOP (GB, 1934) WRL/2/1 Typewritten list of cast and contracted rates of pay, nd. DANDY DICK (GB, 1935) WRL/3/1 Typewritten list of cast and contracted rates of pay, nd. MUSIC HATH CHARMS (GB, 1935) WRL/4/1 Typewritten list of cast and contracted rates of pay, nd. -

At the OLD GLOBE THEATRE MARCH/APRIL 2011 Welcome To

at the OLD GLOBE THEATRE MARCH/APRIL 2011 Welcome to THE GLOBE AT A GLANCE The sixth-largest regional Our main stage season theatre in the country, is about families. From The Old Globe offers more Brighton Beach to Osage programming and a greater County and in between, repertoire than any theatre Bolton, England. These plays of its size. reveal what we know — that • • • WORONOWICZ KATARZYNA J. families have the same basic As a not-for-profit theatre concerns and needs despite with an annual budget their geographic and cultural averaging $20 million, the differences. In Rafta, Rafta… Globe earns $10 million in we are introduced to an ticket sales and must raise an immigrant Indian family whose relationships between parents and additional $10 million from children and husband and wife will feel all too familiar to many of us. individual and institutional tax-deductible donations. Ayub Khan–Din, one of the most prominent playwrights working in England, based his play on All in Good Time by Bill Naughton (author • • • of Alfie). Ayub smartly saw the similarities between working class The Globe provides more English families of the 1960s and modern Indian families in Britain. than 20 different community and education programs Director Jonathan Silverstein’s productions in New York have been to nearly 50,000 people hailed, and I’m pleased to bring him back to San Diego. Joining annually. him in realizing the world of Rafta, Rafta… are designers whose work has enlivened past productions: Alexander Dodge for sets, • • • Christal Weatherly (who was a classmate of Jonathan’s at UCSD) for The Old Globe has sent 20 costumes, Lap Chi Chu for lights and Paul Peterson for sound. -

Theatre Archive Project

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Jan Carey – interview transcript Interviewer: Charlotte D'Arcy 13 November 2009 Actress. Assistant Stage Manager; auditions; critics; female roles; The Guildhall School of Music and Drama; Arthur Gurney; Mermaid Theatre; Arthur Miller; musicals; Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond; repertory; Paul Scofield; Spring and Port Wine; theatre-going; television; theatre in the round. CD: Hi Jan. Thank you very much for joining us at the British Library today to talk about your theatre history. Can I just ask – as a first question – how did you get into the theatre? Did you go when you were a youngster or… JC: I was always very lucky because my mother used to take us a lot to the theatre. We lived near Portsmouth – Southsea - and there was the King’s Theatre Southsea, which had all the post- and prior-West End plays and operas, ballets, you name it. We used to go once a week when I was… I suppose from the age of about ten or eleven, and sit in the pit, which was wonderful, which you had in those days. So I saw a great deal and I was very lucky and I always loved going and was never prevented from going, so it was never really an issue. It was great, I saw an awful lot. CD: What kind of things were your favourite? You said you had ballets and plays and… JC: Yes, well I saw the tour after the original West End Look Back in Anger. The London cast – that was Alan Bates and Kenneth Haig and Mary Ure, and I can’t remember who played Helena. -

Download This PDF File

Postcolonial Text, Vol 6, No 2 (2011) Glocal Routes in British Asian Drama: Between Adaptation and Tradaptation Giovanna Buonanno University of Modena and Reggio Emilia Victoria Sams Dickinson College, Carlisle Christiane Schlote University of Zurich In the context of British Asian theatre and the search for a diasporic theatre aesthetics, the practice of adaptation has emerged as a recurring feature.1 Over the last decades, British Asian theatre has sought to create a language of the theatre that can reflect the cultural heritage of Asians in Britain, while also responding to the need to challenge the conceptual binary of British and Asian. The plurality of voices that today make up British Asian theatre share a common, if implicit, aim of affirming South Asian culture on the stage as an integral part of British culture. As Dominic Hingorani has pointed out, “British Asian theatre has not only been concerned with the reproduction of culturally „traditional‟ forms from the South Asian subcontinent … but has also focused on the contemporary frame and the emergence of new and dynamic forms as a result of this hybrid cultural location” (7). As this article will argue, adaptations as cultural relocations can provide an effective strategy for mapping this hybrid cultural location. Through their revisionist approach to intertextuality, these adaptations also highlight the dialectic between the local and the global, whether in their recreation of regions, such as the northwest of Britain as South Asian British cultural spaces, or of the entangled histories of South Asian and European epic and theatrical traditions. The connotations of the terms “adaptation” and “routes” speak to this tension between the immediate environmental demands and the farther-reaching forces that shape the lives of migrants and where, as James Clifford has shown, the old adage of “roots always precede routes” (3) has been overturned. -

Ebook ^ Alfie (Film Tie-In Edition) / Read

5RDQWPDQLM Alfie (Film tie-in edition) // Doc A lfie (Film tie-in edition) By Bill Naughton Allison & Busby. Paperback. Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Alfie (Film tie-in edition), Bill Naughton, "I???ve got this dark little lump of cold grief or something over my heart. It could, of course, be wind."And that??'s Alfie really. Never one to take himself, or anything else for that matter, too seriously. He???ll never say no to a woman and he???ll even let them stay the night, as long as they cook breakfast of course and as long as they never, ever, ask when he???ll be back. But these things are never that simple, even if Alfie likes to pretend they are. There??'s meek little Annie, who??'s almost got him "poncified"; Ruby, a bit old but in fabulous condition and then the less said about Lily the better. But Alfie doesn???t do complicated. He loves, he leaves and when he occasionally wrestles with his conscience, he always wins. Well, almost always. .With sales of over a million copies since its first publication in 1966, Alfie is a controversial modern classic. The inspiration for the cult film starring Michael Caine and the smash-hit remake with Jude Law as the eponymous anti-hero, Alfie feels as fresh and relevant today as when it was... READ ONLINE [ 3.45 MB ] Reviews An extremely awesome publication with lucid and perfect explanations. It is actually writter in basic phrases rather than confusing. You will like how the writer publish this book. -

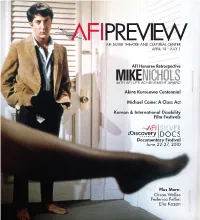

Michael Caine: a Class Act

AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER APRIL 16 - JULY 1 AFI Honoree Retrospective Akira Kurosawa Centennial Michael Caine: A Class Act Korean & International Disability Film Festivals Documentary Festival June 22-27, 2010 JUNE 22-27 2010 Plus More: Orson Welles Federico Fellini Elia Kazan Photo Courtesy of Janus Films THRONE OF BLOOD MICHAEL CAINE: A CLASS ACT MAY 14 - JULY 1 THE IPCRESS FILE GET CARTER FRI, MAY 14, 9:15; SAT, MAY 15, 10:10; THU, MAY 20, 9:15 FRI, MAY 21, 9:30; SAT, MAY 22, 9:45; TUE, MAY 25, 7:00 Looking for a different spin on the spy genre, Harry Saltzman, “You’re a big man, but you’re in co-producer on the early James Bond fi lms (and LOOK BACK bad shape. With me it’s a full- IN ANGER, a huge infl uence on Caine’s generation), cast time job. Now behave yourself.” Caine as the bespectacled Harry Palmer, unimposing and Caine’s existential hard man Jack put-upon by his hardcase superiors. Palmer may be a working Carter is Gangster Number One stiff, but he’s a wised-up one, subtly sarcastic and wary of the in this hugely infl uential, neo-noir old-boy network that’s made a mess of MI6; just the man to classic from talented writer/ root out a traitor in the ranks, as he is called on to do. Director director Mike Hodges. Traveling Sidney J. Furie, famously disdainful of the script (he set at least up from London to Newcastle one copy on fi re) goes visually pyrotechnic with trick shots, after his brother’s mysterious tilted angles, color fi lters and a travelogue’s worth of London death, Carter begins kicking locations. -

Indigo 2 TRA:Layout 1

P7 Find the Word: Gravestone for Titanic Fall Boy plunged, connected, vessel, construction, unveiled, voyage, haunts, fracture, luxury, striking, iceberg, ceremony P9 Literacy Workout 1 Filling the Blanks: Bats Bats are the only mammals that have wings and are capable of flight. Many are grotesque- looking animals with huge ears and strange faces. They produce high-pitched sounds which bounce off nearby objects. This ‘echo’ is picked up by the bat’s large ears, and the bat uses it to locate its prey and avoid obstacles. This is called echolocation. Almost a quarter of all mammal species alive in the world today are bats. Nearly all are nocturnal - active only at night. Most eat insects, but some feed on larger creatures such as mice, or other bats. A few catch fish, and three species take blood from large birds or mammals. Some bats feed on nectar and are important in carrying pollen from flower to flower, while others are fruit eaters. Most bats fly more slowly than birds, but have more control. They can turn, twist and fly without hesitation, through small gaps that would defeat the majority of birds. Flight uses a lot of energy. Most bats conserve their resources by letting their temperatures drop and remaining still when they are not flying. In cool parts of the world bats hibernate in winter, but a few species migrate to where there are better supplies of food. There are still huge populations of many sorts of bats, but others are becoming rare, as a result of pollution and changes in the environment. -

American Remakes of the British Films Elif Kahraman Dönmez, Istanbul Arel University [email protected]

Let’s Make it American: American Remakes of the British Films Elif Kahraman Dönmez, Istanbul Arel University [email protected] Volume 7.1 (2018) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI /cinej.2018.221 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract The purpose of this study is to analyze American remake versions of the original British films taking narrative as a basis. It claims that the American remakes put America forward as a cultural product for sale, and makes the British narrative Americanized. For the study, two sets of film remakes have been chosen for analysis: Alfie (1966, dir. Lewis Gilbert), Alfie (2004, dir. Charles Shyer), Bedazzled (1967, dir. Stanley Donen), Bedazzled (2000, dir. Harold Ramis). This study explores the narrative elements of the American remakes by comparing the remakes with their originals. These narrative elements are setting, intertextuality and Americanization. Keywords: Remake, American Cinema, Film, Narrative, Americanization, Intertextuality New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Let’s Make it American: American Remakes of the British Films Elif Kahraman Dönmez Introduction Cinema in 21st century offers varieties, especially American cinema, Hollywood, is a global narrative reproduction machine. Interestingly enough, Hollywood needs the previous film stories to capture and remake new ones, a process referred to as the remake. It is important to point out the differences between an adaptation and a remake. -

Cinematic Treatment of Abortion: Alfie (1965) and the Cider House Rules (1999)

Cinematic Treatment of Abortion: Alfie (1965) and The Cider House Rules (1999) Jeff Koloze ABSTRACT This paper examines the cinematic portrayal of abortion in the films Alfie (1965) and The Cider House Rules (1999) from the right-to-life perspective. Various aspects of the abortion content of each of the films are considered, including criticism from academia and commentary on the fidelity to the written works on which the films are based. A substantial part of the paper comments on the effects on the audience of camera angles, images, use of color, and the other cinematic techniques that construct the abortion scenes. Finally, the paper evaluates the perspective on abortion suggested in each film and determines which film is more worthy of study and artistic appreciation. HE ICONS OF CONTEMPORARY CULTURE are cinematic. Certainly, for example, the famous still photograph of the young woman kneeling Tand shrieking over the dead body of her fellow Kent State student is iconic. Contemporary icons, however, demonstrate a kinetic quality not only to be enjoyed in a theater or at home, but also to be worthy of continued critical discussion. The scene of epiphany between the tramp and the young woman whose sight he helped to restore in Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights is as poignant today as it was in 1931. Kim Novak’s slow and sensual walk towards Jimmy Stewart in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) is as iconic as Gloria Swanson’s final walk towards the camera in Sunset Boulevard (1950) or the famous shower scene in Psycho (1960). Moreover, films occupy an important part of contemporary culture.