Scientists in Pixar's New Looks Project Work out a Long

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subdivision Surfaces Years of Experience at Pixar

Subdivision Surfaces Years of Experience at Pixar - Recursively Generated B-Spline Surfaces on Arbitrary Topological Meshes Ed Catmull, Jim Clark 1978 Computer-Aided Design - Subdivision Surfaces in Character Animation Tony DeRose, Michael Kass, Tien Truong 1998 SIGGRAPH Proceedings - Feature Adaptive GPU Rendering of Catmull-Clark Subdivision Surfaces Matthias Niessner, Charles Loop, Mark Meyer, Tony DeRose 2012 ACM Transactions on Graphics Subdivision Advantages • Flexible Mesh Topology • Efficient Representation for Smooth Shapes • Semi-Sharp Creases for Fine Detail and Hard Surfaces • Open Source – Beta Available Now • It’s What We Use – Robust and Fast • Pixar Granting License to Necessary Subdivision Patents graphics.pixar.com Consistency • Exactly Matches RenderMan Internal Data Structures and Algorithms are the Same • Full Implementation Semi-Sharp Creases, Boundary Interpolation, Hierarchical Edits • Use OpenSubdiv for Your Projects! Custom and Third Party Animation, Modeling, and Painting Applications Performance • GPU Compute and GPU Tessellation • CUDA, OpenCL, GLSL, OpenMP • Linux, Windows, OS X • Insert Prman doc + hierarchical viewer GPU Performance • We use CUDA internally • Best Performance on CUDA and Kepler • NVIDIA Linux Profiling Tools OpenSubdiv On GPU Subdivision Mesh Topology Points CPU Subdivision VBO Tables GPU Patches Refine CUDA Kernels Tessellation Draw Improved Workflows • True Limit Surface Display • Interactive Manipulation • Animate While Displaying Full Surface Detail • New Sculpt and Paint Possibilities Sculpting & Ptex • Sculpt with Mudbox • Export to Ptex • Render with RenderMan • Insert toad demo Sculpt & Animate Too ! • OpenSubdiv Supports Ptex • OpenSubdiv Matches RenderMan • Enables Interactive Deformation • Insert rendered toad clip graphics.pixar.com Feature Adaptive GPU Rendering of Catmull-Clark Subdivision Surfaces Thursday – 2:00 pm Room 408a . -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor . -

The Metaverse and Digital Realities Transcript Introduction Plenary

[Scientific Innovation Series 9] The Metaverse and Digital Realities Transcript Date: 08/27/2021 (Released) Editors: Ji Soo KIM, Jooseop LEE, Youwon PARK Introduction Yongtaek HONG: Welcome to the Chey Institute’s Scientific Innovation Series. Today, in the 9th iteration of the series, we focus on the Metaverse and Digital Realities. I am Yongtaek Hong, a Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Seoul National University. I am particularly excited to moderate today’s webinar with the leading experts and scholars on the metaverse, a buzzword that has especially gained momentum during the online-everything shift of the pandemic. Today, we have Dr. Michael Kass and Dr. Douglas Lanman joining us from the United States. And we have Professor Byoungho Lee and Professor Woontack Woo joining us from Korea. Now, I will introduce you to our opening Plenary Speaker. Dr. Michael Kass is a senior distinguished engineer at NVIDIA and the overall software architect of NVIDIA Omniverse, NVIDIA’s platform and pipeline for collaborative 3D content creation based on USD. He is also the recipient of distinguished awards, including the 2005 Scientific and Technical Academy Award and the 2009 SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics Achievement Award. Plenary Session Michael KASS: So, my name is Michael Kass. I'm a distinguished engineer from NVIDIA. And today we'll be talking about NVIDIA's view of the metaverse and how we need an open metaverse. And we believe that the core of that metaverse should be USD, Pixar's Universal Theme Description. Now, I don't think I have to really do much to introduce the metaverse to this group, but the original name goes back to Neal Stephenson's novel Snow Crash in 1992, and the original idea probably goes back further. -

Toy Story." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Donaldson, Lucy Fife. " Rough and Smooth: The Everyday Textures of Toy Story." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 73–86. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 03:07 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 73 Chapter 5 R OUGH AND SMOOTH: THE EVERYDAY TEXTURES OF T OY STORY Lucy Fife Donaldson As one of the fi rst fully computer- generated imagery (CGI) fi lms, it is not sur- prising that Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995) fi gures prominently in debates about both the technical achievements of digital imaging and the anxieties con- cerning absence in digital fi lmmaking, particularly the perceived inherent lack of materiality in its processes and fi nal product. As CGI exponentially enlarges the plasticity of a fi ctional world, the inevitable emphasis on plastic surfaces within a fi lm that focuses on children’s toys seems to magnify the concerns of the latter camp, causing writers to equate its constitution with insubstanti- ality, fi nding the fi lm to be dominated by a processed smoothness that corre- sponds to the feel of CGI more generally. As Ian Garwood puts it, the concern is that ‘the infi nite manipulability of the image betrays its fatal lack of real- world robustness’. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY William W. Armstrong and Mark W. Green. Visual Computer, chapter The dynamics of artic- ulated rigid bodies for purposes of animation, pages 231–240. Springer-Verlag, 1985. David Baraff. Analytical methods for dynamic simulation of non-penetrating rigid bodies. Computer Graphics, 23(3):223–232, July 1989. Alan H. Barr. Global and local deformations of solid primitives. Computer Graphics, 18:21– 29, 1984. Proc. SIGGRAPH 1984. Ronen Barzel and Alan H. Barr. Topics in Physically Based Modeling, Course Notes, vol- ume 16, chapter Dynamic Constraints. SIGGRAPH, 1987. Ronen Barzel and Alan H. Barr. A modeling system based on dynamic constaints. Computer Graphics, 22:179–188, 1988. Armin Bruderlin and Thomas W. Calvert. Goal-directed, dynanmic animation of human walk- ing. Computer Graphics, 23(3):233–242, July 1989. John E. Chadwick, David R. Haumann, and Richard E. Parent. Layered construction for de- formable animated characters. Computer Graphics, 23(3):243–252, 1989. Proc. SIGGRAPH 1989. J. S. Duff, A. M. Erisman, and J.K. Reid. Direct Methods for Sparse Matrices. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1986. Kurt Fleischer and Andrew Witkin. A modeling testbed. In Proc. Graphics Interface, pages 127–137, 1988. Phillip Gill, Walter Murray, and Margret Wright. Practical Optimization. Academic Press, New York, NY, 1981. Michael Girard and Anthony A. Maciejewski. Computational Modeling for the Computer Animation of Legged Figures. Proc. SIGGRAPH, pages 263–270, 1985. Michael Gleicher and Andrew Witkin. Creating and manipulating constrained models. to appear, 1991. Michael Gleicher and Andrew Witkin. Snap together mathematics. In Edwin Blake and Peter Weisskirchen, editors, Proceedings of the 1990 Eurographics Workshop onObject Oriented Graphics. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

Press Release

Press release CaixaForum Madrid From 21 March to 22 June 2014 Press release CaixaForum Madrid hosts the first presentation in Spain of a show devoted to the history of a studio that revolutionised the world of animated film “The art challenges the technology. Technology inspires the art.” That is how John Lasseter, Chief Creative Officer at Pixar Animation Studios, sums up the spirit of the US company that marked a turning-point in the film world with its innovations in computer animation. This is a medium that is at once extraordinarily liberating and extraordinarily challenging, since everything, down to the smallest detail, must be created from nothing. Pixar: 25 Years of Animation casts its spotlight on the challenges posed by computer animation, based on some of the most memorable films created by the studio. Taking three key elements in the creation of animated films –the characters, the stories and the worlds that are created– the exhibition reveals the entire production process, from initial idea to the creation of worlds full of sounds, textures, music and light. Pixar: 25 Years of Animation traces the company’s most outstanding technical and artistic achievements since its first shorts in the 1980s, whilst also enabling visitors to discover more about the production process behind the first 12 Pixar feature films through 402 pieces, including drawings, “colorscripts”, models, videos and installations. Pixar: 25 Years of Animation . Organised and produced by : Pixar Animation Studios in cooperation with ”la Caixa” Foundation. Curator : Elyse Klaidman, Director, Pixar University and Archive at Pixar Animation Studios. Place : CaixaForum Madrid (Paseo del Prado, 36). -

An Introduction to Physically Based Modeling: an Introduction to Continuum Dynamics for Computer Graphics

An Introduction to Physically Based Modeling: An Introduction to Continuum Dynamics for Computer Graphics Michael Kass Pixar Please note: This document is 1997 by Michael Kass. This chapter may be freely duplicated and distributed so long as no consideration is received in return, and this copyright notice remains intact. An Introduction to Continuum Dynamics for Computer Graphics Michael Kass Pixar 1 Introduction Mass-spring systems have been widely used in computer graphics because they provide a simple means of generating physically realistic motion for a wide range of situations of interest. Even though the actual mass of a real physical body is distributed through a volume, it is often possible to simu- late the motion of the body by lumping the mass into a collection of points. While the exact coupling between the motion of different points on a body may be extremely complex, it can frequently be ap- proximated by a set of springs. As a result, mass-spring systems provide a very versatile simulation technique. In many cases, however, there are much better simulation techniques than directly approximating a physical system with a set of mass points and springs. The motion of rigid bodies, for example, can be approximated by a small set of masses connected by very stiff springs. Unfortunately, the very stiff springs wreak havoc on the numerical solution methods, so it is much better to use a technique based on the rigid-body equations of motion. Another important special case arises with our subject here: elastic bodies and ¯uids. In many cases, they can be approximated by regular lattices of mass points and springs. -

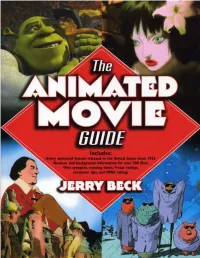

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

A Learning-Based Approach to Parametric Rotoscoping of Multi-Shape Systems

A Learning-Based Approach to Parametric Rotoscoping of Multi-Shape Systems Luis Bermudez Nadine Dabby Yingxi Adelle Lin Intel Corporation Intel Corporation Intel Corporation [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sara Hilmarsdottir Narayan Sundararajan Swarnendu Kar Intel Corporation Intel Corporation Intel Corporation [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract artifacts to be imperceptible to the human eye, and they must be parametric so that an artist can iteratively modify Rotoscoping of facial features is often an integral part of them until the composite meets their rigorous standard. The Visual Effects post-production, where the parametric con- high standards and stringent requirements of state-of-the- tours created by artists need to be highly detailed, con- art rotoscoping still requires a significant amount of manual sist of multiple interacting components, and involve signif- labor from live action and animated films. icant manual supervision. Yet those assets are usually dis- We apply machine learning to automate rotoscoping in carded after compositing and hardly reused. In this paper, the post-production operations of stop-motion filmmaking, we present the first methodology to learn from these assets. in collaboration with LAIKA, a professional animation stu- With only a few manually rotoscoped shots, we identify and dio. LAIKA has a unique facial animation process in which extract semantically consistent and task specific landmark puppet expressions are comprised of multiple 3D printed points and re-vectorize the roto shapes based on these land- face parts that are snapped onto and off of the puppet over marks. -

Theatrical Shorts Home Entertainment Shorts Sparkshorts Toy Story Toons Disney + Cars Toons

Documento número 1 THEATRICAL SHORTS HOME ENTERTAINMENT SHORTS SPARKSHORTS TOY STORY TOONS DISNEY + CARS TOONS 35 Las aventuras de André y Wally B. Luxo Jr. Año 1984 Año 1986 Duración 2 minutos Duración 92 segundos Dirección Alvy Ray Smith Dirección John Lasseter El Sueño de Red Tin Toy Año 1987 Año 1988 Duración 4 minutos Duración 5 minutos Dirección John Lasseter Dirección John Lasseter 36 La Destreza de Knick Geri’s game Año 1989 Año 1997 Duración 4 minutos Duración 5 minutos Dirección John Lasseter Dirección Jan Pinkava Vuelo de Pájaros Boundin’ Año 2000 Año 2003 Duración 3 minutos y 27 Duración 5 minutos segundos Dirección Ralph Eggleston Dirección Bud Luckey 37 El hombre orquesta Lifted Año 2006 Año 2007 Duración 4 minutos y 33 Duración 5 minutos segundos Dirección Andrew Jimenez Dirección Gary Rydstrom Presto Parcialmente nublado Año 2008 Año 2009 Duración 5 minutos y 17 Duración 5 minutos y 45 segundos segundos Dirección Doug Sweetland Dirección Peter Sohn 38 Día & Noche La Luna Año 2010 Año 2012 Duración 5 minutos y 57 Duración 7 minutos segundos Dirección Teddy Newton Dirección Enrico Casarosa Party central Azulado Año 2014 Año 2013 Duración 6 minutos Duración 7 minutos Dirección Kelsey Mann Dirección Saschka Unseld 39 Lava Sanjay’s Super Team Año 2015 Año 2015 Duración 7 minutos Duración 7 minutos Dirección James Ford Murphy Dirección Sanjay Patel Piper: Esperando la Marea Lou Año 2016 Año 2017 Duración 6 minutos Duración 6 minutos Dirección Alan Barillaro Dirección Dave Mullins 40 Bao Mike’s New Car Año 2018 Año 2002 Duración 8 minutos Duración 4 minutos Dirección Domee Shi Dirección Pete Docter Roger L.