The Realisation of the Rotunda of Mosta, Malta: Grognet, Fergusson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 366 March 2021

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 366 March 2021 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 366 March 2021 PRESS RELEASE BY THE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT ‘L-Istat tan-Nazzjon’ (State of the Nation) national survey and conference launched in collaboration with the Office of the President President urged the public to cooperate in the gathering of information during the survey. He also said that there is nothing wrong if such discussions are also held at the local level in different parts of our country. “This is all part of my vision for this year, which I would like to dedicate to this goal. I am taking these steps so that the presidency creates awareness of historical moments in the shaping of our country, our achievements and, above all, President of Malta George Vella presided over a press knowledge and appreciation of where we are conference announcing a scientific survey and today,” said the President. “While we continue to be national conference, under the theme ‘L-Istat tan- critical of all that is wrong around us, we must Nazzjon’ (State of the Nation), which will analyse cherish all the positive that we have gained wisely how the Maltese national identity is evolving. This and carefully over time.” initiative, which will be held regularly, is being taken by strategic communications consultant Lou Bondì Dr Marmarà explained that the survey will be and university statistician and lecturer Vincent conducted by telephone with no less than a Marmarà, in collaboration with the Office of the thousand people from among the entire population President. of Maltese citizens. The goal is to gain a better understanding of who we are as a nation and what “Rather than ‘who we are’, we will be discussing we believe in, what defines us, and what shapes our ‘who we have become’, as we are an evolving and principles. -

Viaggiatori Della Vita JOURNEY to MALTA: a Mediterranean Well

Viaggiatori della vita organises a JOURNEY TO MALTA: A Mediterranean well concerted lifestyle View of Valletta from Marsamxett Harbour. 1st Travel Day The tour guide (if necessary, together with the interpreter) receives the group at Malta International Airport (Luqa Airport) and accompanies it to the Hotel [first overnight stay in Malta] 2nd Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the main historical places of Valletta, the capital of Malta; a city guide provides background knowledge during a walk of about 1 ½ to 2 hours to the most interesting places. Leisure time and shopping tour in Valletta. [second overnight stay in Malta] Valletta Historical centre of Valletta View from the Upper Barracca Gardens to the Grand Harbour; the biggest natural harbour of Europe. View of Lower Barracca Gardens 3rd Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the main places worth visiting in Sliema and St. Julian's. Leisure time. [third overnight stay in Malta] Sliema, Malta. Sliema waterfront twilight St. Julian's Bay, Malta. Portomaso Tower, St. Julian's, Malta. 4th Travel Day The tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group to visit the most famous places of interest in Gozo (Victoria / Rabat, Azure Window, Fungus Rock, Blue Grotto and so forth) [fourth overnight stay in Malta] Azure Window, Gozo. Fungus Rock (the General's Rock), at Dwejra, Gozo. View from the Citadel, Victoria, capital city of Gozo. Saint Paul's Bay, Malta. 5th Travel Day Journey by coach to different localities of Malta; the tour guide and the interpreter accompany the group. -

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

AUCTION at Villa Drusilla, Mdina Road, Attard

SALE BY AUCTION at Villa Drusilla, Mdina Road, Attard. Ref: 200 - Antiques & Fine Arts 21438220 or 21472156 Viewing 06 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 06:00 PM 07 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 06:00 PM 08 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 06:00 PM 09 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 06:00 PM 10 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 12:00 PM 11 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 12:00 PM 12 December 2015 from 10:00 AM to 12:00 PM Auction Session 1 10 December 2015 at 04:30 PM Lot 1 to Lot 280 Session 2 11 December 2015 at 04:30 PM Lot 281 to Lot 530 Session 3 12 December 2015 at 02:30 PM Lot 531 to Lot 757 Important notice to buyers All goods bought must be collected on Monrings of Auction till 12 noon or from Monday 14th till Thursday 17th December 2015, from 9am till 4pm, Please refer to 'Conditions of Business'. All Obelisk Auctions Clients must register before or during each and every auction session and take a bidding card, so as to be able to participate in the auction session(s). Please register your details with Obelisk Auctions so as to receive notifications of forthcoming events, either direct through our web site www.obeliskauctions.com or by completing one of our registration forms. Transportation We recommend that clients who require transportation for items bought at the auction, should contact Nicholas Borg on 9944-8456 or Noel Xuereb on 9947-3531. -

First Occurences of Lemna Minuta Kunth (Fam

The Central Mediterranean Naturalist 5(2): 1-4 Malta, December 2010 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ FIRST OCCURENCES OF LEMNA MINUTA KUNTH (FAM. LEMNACEAE) IN THE MALTESE ISLANDS Stephen MIFSUD1 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The occurrence of Lemna minuta Kunth in the Maltese Islands is reported for the first time, from two sites in Malta and one site in Gozo. Notes on its historical and current distribution in Europe, its invasive properties and its habitat preferences in Malta are given. Also included are the distinguishing morphological features from the closely related Lemna minor L., another frequent alien species of ponds and valleys in the Maltese islands. Keywords: Lemna minuta, valleys, watercourses, alien species, invasive species, flora of Malta INTRODUCTION Lemna minuta Kunth (synonyms: L. minuscula Heter ; L. minima Phil ex Hegelm) commonly known as Least Duckweed, is native to the eastern area of North America, western coasts of Mexico and stretches in temprate zones in Central and South America (Mesterházy et al., 2007). It was introduced into Europe in the last third of the 20th Century where, soon after, it had become naturalised in several European countries. It was first recorded in Europe erroneously as L. valdiviana from Biarritz, South West of France in 1965 and then as L. minuscula from Cambridge, UK in 1977 (Landolt, 1979 cited in Lacey, 2003). Today, 45 years after its first published occurrence, L. minuta is widespread throughout Europe and it is recorded from France, England, Belgium, Germany, (GRIN; GBIF), Switzerland, Ukraine (GRIN), Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden (GBIF), Ireland (Lacey, 2003), Hungary (Mesterházy et al., 2007), Slovakia (Feráková & Onderíková, 1998), Romania (Ciocârlan, 2000), Greece (Landolt, 1986), Austria (Fischer et al., 2005) and Italy (Desfayes, 1993 cited in Iamonico et al., 2010 ; Conti et al., 2005). -

BELLEZAS DE MALTA Dwejra La Valletta, Gozo, Mdina, Mosta, Rabat Xlendi Las Tres Ciudades: Senglea, Victoriosa, Cospicua Mgarr Isla COMINO

La ventana azul Isla GOZO Santuario de Ta´Pinu Mar interior BELLEZAS DE MALTA Dwejra La Valletta, Gozo, Mdina, Mosta, Rabat Xlendi Las Tres Ciudades: Senglea, Victoriosa, Cospicua Mgarr Isla COMINO Cirkewwa PENSIÓN COMPLETA Además de la visita a La Valletta se incluye • Visita de la Catedral y Palacio del Gran Maestre • Visita a Senglea, Victoriosa y Cospicua Isla MALTA • Excursión a la Isla de Gozo Mosta • Visita a Mdina, Rabat y Mosta Mdina La Valletta • Paseo en góndola maltesa Rabat Senglea Victoriosa Cospicua SUP días, ...en Hoteles 4****/3*** (M50) 8 DÍA 1. (Jueves) ESPAÑA-MALTA de los lugares de veraneo más frecuentado inmediaciones. A continuación iremos a visi- FECHAS DE SALIDA Presentación en el aeropuerto para embarcar tanto por turistas como por los habitantes del tar los complejos de templos megalíticos de 2021 en avión con destino Malta. Llegada, asisten- lugar. Breve parada en el Mirador Qala que Hagar Qim y Mnajdra. Tarde libre. Cena y cia en el aeropuerto y traslado al hotel. Alo- ofrece preciosas vistas de Comino y Malta. alojamiento. Mayo 13 20 27 jamiento. Regreso a Malta. Cena y alojamiento. Junio 3 10 17 24 DÍA 8. (Jueves) MALTA-ESPAÑA Septiembre 2 9 16 23 DÍA 5. (Lunes) MALTA: MOSTA-MDINA-RABAT DÍA 2. (Viernes) MALTA: LAS TRES CIUDADES: Desayuno buffet. A la hora que se indique Octubre 7 14 SENGLEA, VICTORIOSA, COSPICUA Desayuno. Hoy conoceremos Mosta, Mdina traslado al aeropuerto de Malta para embar- y Rabat. Salida hacia Mosta, centro geográ- car en avión con destino España. Fin del viaje Desayuno. Hoy conoceremos la zona de Cot- Descuento por reserva anticipada. -

SALE by AUCTION at Villa Drusilla, No.1, Mdina Road, Attard

SALE BY AUCTION at Villa Drusilla, No.1, Mdina Road, Attard. Ref: 229 - Antiques & Fine Arts, Obelisk Auctions Gallery. Viewing Saturday 21 October 2017 from 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Sunday 22 October 2017 from 10:00 am to 6:00 pm Mornings of Auction from 10:00 am to 12 noon Auction Session 1 Monday 23 October 2017 at 4:30 pm Lot 1 to Lot 190 Session 2 Tuesday 24 October 2017 at 4:30 pm Lot 191 to Lot 399 Session 3 Wednesday 25 October 2017 at 4:30 pm Lot 400 to Lot 590 Session 4 Thursday 26 October 2017 at 4:30 pm Lot 591 to Lot 767 Session 5 Friday 27 October 2017 at 4:30 pm Lot 768 to Lot 905 Session 6 Saturday 28 October 2017 at 2:30 pm Lot 906 to Lot 1130 Important notice to buyers 1. All Obelisk Auctions Clients must register before or during each and every auction session and take a bidding card, so as to be able to participate in the auction session(s). 2. Please register your details with Obelisk Auctions so as to receive notifications of forthcoming events direct through our web site www.obeliskauctions.com. 3. Please refer to 'Conditions of Business'. 4. The prices indicated in the catalogue are the Auction starting prices. Items bought can be collected on the following day of each auction session between 10 am and 12 noon. Buyers must collect the lots purchased from Monday 30th October till Wednesday 1st November 2017, between 9am and 4pm. -

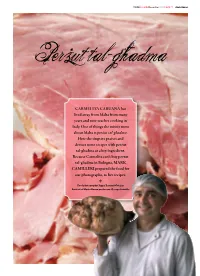

Perzut Tal-Ghadma

Tasteissue34December2009Page27 christmas Perzut tal-ghadma CARMELITA CARUANA has lived away from Malta from many years and now teaches cooking in Italy. One of things she misses most about Malta is perżut tal-għadma. Here she sings its praises and devises some recipes with perżut tal-għadma as a key ingredient. Because Carmelita can’t buy perżut tal-għadma in Bologna, MARK CAMILLERI prepared the food for our photographs, to her recipes. ✥ Food photography: Pippa Zammit Cutajar Portrait of Mosta Bacon producers: George Scintilla christmas Tasteissue34December2009Page28 ere perżut tal-għadma an Italian product, its praises would be sung far and wide. It would be hung with medals and protected from inferior imitations made elsewhere by I.G.P and D.O.P designations. And it would be referred to as “Sua Maestà, il Prosciutto Cotto di Malta”. Living in Bologna, Italian Wfood capital and home to superlative raw and cured pork products, I know a top level product when I taste it, and can imagine the praise Italian gourmets would shower on our superb cooked ham. It has never ceased to me amaze me that perżut tal-għadma - sometimes called perżut tal-koxxa but identified by those who make it as perżut tal-għadma, the bone being a crucial element - has such a low profile, going unnoticed and unmentioned. We rightly sing the praises of our bread, capers, gbejniet, zalzett and pastizzi but never a word about our superb ham, perhaps because people erroneously believe it is an imported product. I do what I can to boost its reputation, raving about it to everyone, inviting people to inhale and savour the perfumes as I unwrap the package just brought home. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 329 July 2020 FRANK SCICLUNA RETIRES… I WOULD LIKE INFORM MY READERS that I am retiring from the office of honorary consul for Malta in South Australia after 17 years of productive and sterling work for the Government of the Republic of Malta. I feel it is the appropriate time to hand over to a new person. I was appointed in May 2003 and during my time as consul I had the privilege to work with and for the members of the Maltese community of South Australia and with all the associations and especially with the Maltese Community Council of SA. I take this opportunity to sincerely thank all my friends and all those who assisted me in my journey. My dedication and services to the community were acknowledged by both the Australian and Maltese Governments by awarding me with the highest honour – Medal of Order of Australia and the medal F’Gieh Ir-Repubblika, which is given to those who have demonstrated exceptional merit in the service of Malta or of humanity. I thank also the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Evarist Bartolo, for acknowledging my continuous service to the Government of the Republic of Malta. I plan to continue publishing this Maltese eNewsletter – the Journal of Maltese Living Abroad which is the most popular and respected journal of the Maltese Diaspora and is read by thousands all over the world. I will publish in my journal the full story of this item in the near future. MS. CARMEN SPITERI On 26 June 2020 I was appointed as the Honorary Consul for Malta in South Australia. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

Vincent Apap

Vincent Apap Vincent Apap (13 November 1909 – 15 February 2003) was a Maltese sculptor. He is well-known for designing various public Vincent Apap monuments and church statues, most notably the Triton Fountain in Born 13 November 1909 Valletta. He has been called "one of Malta's foremost sculptors of the Valletta, Malta [1] Modern Period" by the studio of Renzo Piano. Died 15 February 2003 (aged 93) Biography Malta Nationality Maltese Apap was born in Valletta in 1909, and he was the older Occupation Sculptor brother of the musician Notable work Triton Fountain, and Joseph Apap and the painter various monuments William Apap. He attended and statues the government central Style Modernism school, and in 1920 he began to attend evening classes in Spouse(s) Maria Bencini The Triton Fountain in Valletta, which modelling and drawing. He (m. 1941) was designed by Apap together with was one of the first students Children John Apap the designer Victor Anastasi to enroll in the newly- Nella Apap established School of Art in 1925, where he studied Manon Apap sculpture under Antonio Micallef. In 1927, he won a scholarship to Family Joseph Apap the British Academy of Arts in Rome, studying under the renowned (brother) [2] Maltese sculptor Antonio Sciortino. William Apap (brother) He returned to Malta in 1930, and soon afterwards he won his first commission, the Fra Diego monument in Ħamrun. This made him well-known within Malta's art scene, and he regularly exhibited his works at the Malta Art Amateur Association exhibitions throughout the 1930s. He was appointed assistant modelling teacher at the School of Art in 1934, becoming head of school in 1947. -

L-4 Ta' Diċembru, 2019

L-4 ta’ Diċembru, 2019 25,349 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-13 ta’ Jannar, 2020.