Piloting Knowledge Swaraj: a Hand Book on Indian Science and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitat Mapping of Chinangudi

HABITAT MAPPING OF CHINANGUDI A Study of Chinnangudi Village in connection with Tsunami Reconstruction Project Benny Kuriakose South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies (SIFFS) HABITAT MAPPING OF CHINNANGUDI A Study of Chinnangudi Village in Connection with Tsunami Reconstruction Project Benny Kuriakose South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies June 2006 Habitat Mapping of Chinnangudi Village HABITAT MAPPING OF CHINNANGUDI A Study of Chinnangudi Village in Connection with Tsunami Reconstruction Project Benny Kuriakose South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies June 2006 Habitat Mapping of Chinnangudi Village HABITAT MAPPING OF CHINNANGUDI A Study of Chinnangudi Village in Connection with Tsunami Reconstruction Project June 2006 By Benny Kuriakose Published by V.Vivekanandan for South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies (SIFFS) Karamana, Trivandrum - 695 002, Kerala, INDIA Email: [email protected], Web: http://www.siffs.org Edited by Dr. Ahana Lakshmi Cover Sketch by Pratheep Mony M.G Designed by C.R.Aravindan, SIFFS Printed at St.Joseph Press, Trivandrum South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies C O N T E N T S FOREWORD ................................................................................................................ i PREFACE ................................................................................................................ ii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 1.1 -

54Th AGM of the Ernakulam Branch

ERNAKULAM BRANCH OF SOUTHERN INDIA CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS’ STUDENTS ASSOCIATION OF THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA ICAI BHAWAN, DIWAN’S ROAD, ERNAKULAM, KOCHI – 682016. NOTICE The 54th AGM of the members of the Ernakulam Branch of SICASA of ICAI will be held at 5.30 pm on Friday, 30th July, 2021 at ICAI Bhawan, Ernakulam. The Notice and Annual Report will be hosted on the website of the Ernakulam Branch of Southern India Chartered Accountants Students’ Association [www.sicasaernakulam.in]. The notice of the meeting will also be displayed on the Notice Board at the premises of Ernakulam Branch of the Southern India Regional Council of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India. Students desirous of having hardcopy of the aforesaid documents may email/write with their full details and Students Registration Number to Ms. Shimy Shaji, Secretary, Ernakulam Branch of SICASA, ‘ICAI Bhawan’, Diwan’s Road, Ernakulam , Kochi- 682016 (email [email protected]) before the 17th of July 2021. If Covid-19 protocols not permits for the physical meeting, the Annual General Meeting will be on Virtual mode on the same day at same time. Ms. Shimy Shaji, Secretary, Ernakulam Branch of SICASA ERNAKULAM BRANCH OF SICASA OF ICAI ICAI BHAWAN, Diwan’s Road, Ernakulam, Kochi – 682016. MANAGING COMMITTEE MEMBERS CA. SALIM A : SICASA, CHAIRMAN Krishnagopan SRO0491630 Vice Chairman Shimy Shaji SRO0596416 Secretary Poornendu M Nair SRO0599836 Treasurer Abhishek A Krishnan SRO0593714 Joint secretary Maria Rosheen B Y SRO0493970 Academic Coordinator Saikripa SRO0650107 Academic Coordinator Reshma Joy SRO0682502 Academic Coordinator Nandita D Menon SRO0633506 Academic Coordinator Sachin B Samuel SRO0573780 Academic Coordinator Akshara K A SRO0597831 Academic Coordinator Nehal Najeeb SRO0600710 Academic Coordinator Mezhumkunnath Rahul SRO0646584 Academic Coordinator Nitina R. -

Urban Heritage in Indian Cities

COMPENDIUM OF GOOD PRACTICES Urban Heritage in Indian Cities INSTITUTIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE FOR URBAN HERITAGE INTEGRATION OF HERITAGE IN URBAN RENEWAL FRAMEWORK REVITALIZATION OF URBAN HERITAGE THROUGH URBAN RENEWAL COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION APPROACH Generating AWARENESS ABOUT Heritage 2 NIUA: COMPENDIUM OF GOOD PRACTICES an initiative of URBAN HERITAGE IN INDIAN CITIES 1 First Published 2015 Disclaimer This report is based on the information collected by Indian National Trust for Arts & Cultural Heritage (INTACH) for a study commissioned by the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), from sources believed to be reliable. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information contained herein is not untrue or misleading, NIUA accepts no responsibility for the authenticity of the facts & figures and the conclusions therein drawn by INTACH. 2 NIUA: COMPENDIUM OF GOOD PRACTICES COMPENDIUM OF GOOD PRACTICES Urban Heritage in Indian Cities Prepared by Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage URBAN HERITAGE IN INDIAN CITIES 3 4 NIUA: COMPENDIUM OF GOOD PRACTICES preface The National Institute of Urban Affairs is the National Coordinator for the PEARL Initiative (Peer Experience and Reflective Learning). The PEARL program ensures capacity building through cross learning and effective sharing of knowledge related to planning, implementation, governance and sustainability of urban reforms and infrastructure projects – amongst cities that were supported under the JNNURM scheme. The PEARL initiative provides a platform for deliberation and knowledge exchange for Indian cities and towns as well as professionals working in the urban domain. Sharing of good practices is one of the most important means of knowledge exchange and numerous innovative projects are available for reference on the PEARL website. -

4.4 Post Disaster Management Practices

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Understanding the role of culture in the post disaster reconstruction process: the case of tsunami reconstruction in Tamilnadu, Southern India. Ram Sateesh Pasupuleti School of Architecture and the Built Environment This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2011. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF CULTURE IN THE POST DISASTER RECONSTRUCTION PROCESS THE CASE OF TSUNAMI RECONSTRUCTION IN TAMILNADU, SOUTHERN INDIA RAM SATEESH PASUPULETI A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 Doctor of Philosophy 2011 UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF CULTURE IN THE POST DISASTER RECONSTRUCTION PROCESS THE CASE OF TSUNAMI RECONSTRUCTION IN TAMILNADU, SOUTHERN INDIA Ram Sateesh Pasupuleti University of Westminster School of Architecture and Built Environment London Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECLARATION I confirm that the work submitted is my own, has not been submitted for any other award, and do not contain any copyright material. -

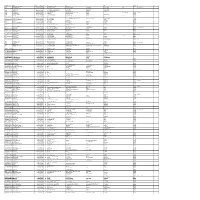

Mgl-Di420- List of Unpaid Shareholders As on 31.12

FOLIO-DEMAT ID NAME NETDIV DWNO MICR AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 CITY PINCOD JH1 JH2 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 204000027 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 204000030 3 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 204000031 4 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 001004 KARTHIKEYAN P.K. 2200.00 204000033 6 PANIKKASSERY HOUSE, THRIPRAYAR POST NATTIKA TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 002769 RAMLATH V E 2200.00 204000037 10 ELLATHPARAMBIL HOUSE NATTIKA BEACH P O THRISSUR KERALA 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 204000041 14 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 204000043 16 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 204000045 18 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 204000046 19 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 204000064 37 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 204000065 38 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 IN30028010510303 JAIN SANJAY KHEMCHAND 1815.00 204000068 41 185 RAVIWAR PETH SATARA 415002 IN30066910186257 B MURALIDHAR 1952.50 204000075 48 D NO 13-56/A KANKIPADU KRISHNA DIST 521151 000697 AMALA S. 4400.00 204000081 54 36 CAR STREET SOWRIPALAYAM COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641028 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 22000.00 204000082 55 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 1202990005855228 SHEJI MATHEW KURIAKOSE 3135.00 204000083 56 658 Ozhukayil House P O Taliparamba Pushpagiri Dt Kannur 670141 003506 KAMALA K 2200.00 204000091 64 SRUTHY NIVAS ALACHANCODE CHITTUR COLLEGE P O CHITTUR PALAKKAD 678104 000637 MURALEEDHARAN T.R. -

Benny Kuriakose Lifetime Achievement

EDITION II www.estrade.in Powered by 6 1 0 2 21|10|2016 S I N G A P O R E BENNY KURIAKOSE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Rewarding the best in Innovation, Business Acumen & BUILT Technological lead in Real Estate & Building Utilities Sector awards 2016 CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL THE 2016 WINNERS 6 1 0 2 About Us 21|10|2016 S I N G A P O R E strade is the digital media Estrade as a media house is dedicated editorial brand of Radar Circle to recognize the efforts of individuals EMedia. Radar Circle Media is a and teams working behind the scenes Singapore based digital media to make their corporate entities reach company operational in Singapore & the pinnacle of success. It is our Mumbai that currently has two endeavor that these teams' success editorial brands Estrade and Onside. stories are shared in the public domain Our endeavor is to provide a platform as case studies for the benefit of all. to a diversity of businesses in a wide Our mission is to reward business spectrum of industries. The company eminence, innovation and wisdom in was founded in 2011 and has been all industries. To create a strong i n v o l v e d i n t h e m e d i a a n d network of enterprising individuals SINGAPORE OFFICE entertainment space since inception. and corporate entities that stands out 18 Sin Ming Lane, Estrade is a corporate news focused in their respective areas of influence. #08 10 Midview City, site, launched in 2014. -

Note from the Convenor

TM Issue no. CMS/01/2020 COUNCIL ON MONUMENTS & SITES Council on Monuments and Sites ICOMOS Image by Priyanka Panjwani Image by Priyanka INDIA June-September 2020 Image of the issue........ CENTRAL VISTA Jansthal, a peoples' place An awareness campaign to retain Delhi's unique heritage for its people. A platform for people from diverse backgrounds to share their thoughts on how to Note from the retainInside.... the significance of this common public place. NORTH ZONE Central Vista Report Convenor by (CVWC) Central Communication - in all its many forms and facets - has always been an important Vista Working Sub- COMOS. Committee component of basic human existence. As such, even before the words ‘Covid-19’ 15th September - 18th October 2020 OPEN CALL FOR ENTRIES I ND I A Central Vista, the main axis of the city of How to Participate: and ‘Corona Virus’ became part of everyday speech, ICOMOS India was ICOMOS India's Central Vista Working Committee invites 04 New Delhi, is a ceremonial path and a public you to share your memories of the Central Vista space, accessible to people from all walks of life. 'Jansthal', a People Place. These could be photos, drawings, illustrations, doodles, video clips or any other already focussing on improving ways of communicating and sharing news and The Government of India has initiated a medium that you may like to send. Supporting captions/ redevelopment plan for the Central Vista. ICOMOS descriptions should not exceed 100-125NORTH words. EAST India is concerned that the dynamics of this Send your entries to [email protected] heritage place will change from being a cultural with the subject line: Our-Central-Vista_ <fullname>. -

Kerala State Electricity Board Limited

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (Incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1956) CIN-U40100KL2011SGCO27424 Office of the Chief Engineer (Human Resource Management) Vydyuthi Bhavanam, Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram - 695004, Kerala Phone : 91-471-2448948 E-mail: [email protected] Fax : 91-471-2441361 Web: www.kseb.in. Transfer and posting of Overseer (Ele) Sub:-Anomalies-Rectification order issued No. EB4(b)/Ovr (Ele)/correction/2018 Dated, TVPM., 24-01-2018 Read:- ORDER The following transfer and posting of Overseers are Ordered SL Name of Employee Present Office [Station] Office to which posted Remarks No [Station] 1 ABDUL AKBAR MM Puthuppady Electrical Thamrassery 66 KV Excess posting Code: 1039443 Section SubstationSection [KOZHIKODE] [KOZHIKODE] 2 ABDUL AZEEZ K K Vazhakkulam Electrical Perumbavoor 110kV Excess posting Code: 1042105 Section Substation [ERNAKULAM] [ERNAKULAM] 3 ABDULJABBAR A M Vazhoor Electrical Section Chengalam 110 KV Sub Excess posting Code: 1041154 [KOTTAYAM] Station [KOTTAYAM] 4 ABDULKARIM P M Puthencruz Electrical Section Kakkanad 66 KV Sub Station Excess posting Code: 1044357 [ERNAKULAM] [ERNAKULAM] 5 AJAYAKUMAR T Chadayamangalam Electrical Ambalapuram 110 KV Sub Excess posting Code: 1040698 Section Station [KOLLAM] [KOLLAM] 6 AJAYAN V Vechoochira Electrical Thriveni 66 KV Sub Station Exscess posting Code: 1040544 Section [PATHANAMTHITTA] [PATHANAMTHITTA] This Document is Generated Online From HRIS Page 1/7 SL Name of Employee Present Office [Station] Office to which posted Remarks No [Station] 7 AJITH -

The Synagogues of Kerala: Their Architecture, History, Context, and Meaning

The Synagogues of Kerala: Their Architecture, History, Context, and Meaning by Jay Arthur Waronker This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: MacDougall,Bonnie Graham (Chairperson) Chusid,Jeffrey M. (Minor Member) THE SYNAGOGUES OF KERALA, INDIA: THEIR ARCHITECTURE, HISTORY, CONTEXT, AND MEANING A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Jay Arthur Waronker August 2010 ©2010 Jay Arthur Waronker ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to record for the first time the architectural history of the functioning, decomissioned but still standing, and lost synagogues in the southernmost Indian State of Kerala on the Malabar Coast. Throughout India, there are today thirty- five existing or former Jewish houses of prayer, built by distinct communities of Jews, dating from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, and the oldest ones are in Kerala. Early Kerala synagogues, realized during the eleventh through the mid-sixteenth century, no longer exist. The Kerala Jewish community, who are believed to have first settled in and around the ancient port town of Cranganore near the Arabian Sea, suffered rounds of persecution during the medieval and early modern periods. In the process, the Jews had to abandon previously built synagogues. Shifting to various places just outside of Cranganore, the Kerala Jews built new synagogues. While some of these houses of prayer likewise do not survive since the Jews remained in locations temporarily or this newer round of synagogues were also attacked and destroyed by hostile human or natural forces, fortunately synagogue construction from the mid-sixteenth century onwards still stands – albeit often in altered states. -

Kerala State Electricity Board Limited

KERALA STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD LIMITED (Incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1956) Office of the Chief Engineer (Human Resources Management) The following transfers and postings of Overseers (Ele.) are ordered Ref:- This office order No.EB.4(b)/OVR/GT/2015 dated, Thiruvananthapuram, 24.08.2015. Sl. Employee Name of Employee Present Office Office to which posted Remarks No. Code VENU P N 110 KV Sub Station 1 1044586 (U/o of transfer vide Sl. No.661 of Transmission Circle, Thrissur Kurumassery the order referred above) ANAND KUMAR K S 220 KV Sub Station New 2 1042884 (U/o of transfer vide Sl. No.46 of Electrical Circle, Vadakara Pallom the order referred above) SHAJI JOHN Thamrassery 66 KV Transmission Circle, 3 1034976 (U/o of transfer vide Sl. No.538 of SubstationSection Poovanthuruthu the order referred above) Thirunavaya (P) Electrical Transmission Circle, 4 1043026 SURESHBABU T K Section Poovanthuruthu West Hill 110 KV 5 1043973 STANELY P T Electrical Circle, Irinjalakkuda SubstationSection SURESH C K 6 1041606 (U/o of transfer vide Sl. No.610 of Electrical Section Mannam Transmission Circle, Thrissur the order referred above) Electrical Circle, 7 1051156 KUMAR S Athani 110 KV Sub Station Thiruvananthapuram (Urban) Mannuthy Electrical Section 8 1050110 JAYAN N K Transmission Circle, Thrissur (Madakkathara) Koorkenchery Electrical 9 1050456 JAYAPRAKASH K Transmission Circle, Thrissur Section 10 1045123 MOHANDAS C K Meloor Electrical Section Transmission Circle, Thrissur Dharmadam Electrical 11 1042951 RATHEESAN K M Transmission Circle, Kannur Section 12 1050439 PRABHASH T Electrical Section, Kuttiyadi Generation Cir le, Thrissur ARUJITH R S 13 1045665 (U/o of transfer vide Sl. -

Dakshinachitra Has a Collection of 18 Authentic Historical Houses with Contextual Exhibitions in Each House

DakshinaChitra has a collection of 18 authentic historical houses with contextual exhibitions in each house. All the houses bought and reconstructed at DakshinaChitra had been given for demolition by their owners. The authentic homes in a regional vernacular style are purchased, taken down, transported and reconstructed by artisans ( Stapathis) of the regions from where the houses came. DakshinaChitra Heritage Museum, a project of Madras Craft Foundation an NGO was opened to the public on December 14th 1996. The Museum is located twenty five kilometers south of Central Chennai, on the East Coast Road to Pondichery, Tamil Nadu, India. It is an exciting cross cultural living museum of art, architecture, lifestyles, crafts and performing arts of South India. We preserve, promote and present the rich cultural heritage of South India through curated permanent exhibits and a variety of public programming. Some of these include Traditional homes from different regions of South India have been purchased, dismantled and relocated at DakshinaChitra .The lifestyle of the communities that lived in these houses has been exhibited in each house. You can explore 18 heritage houses, amble along recreated streetscapes, explore contextual exhibitions, interact with typical village artisans and witness folk performances set in an authentic ambience. DakshinaChitra literally means – “a picture of the south”. We organise collaborative International seminars to create platforms to sustain dialogue about issues of culture in our globalising World…. From 10 acres of undulating sands to a vibrant heritage Museum .. It began as an effort to bring the hidden wealth of South India to light – to set up an institution to celebrate the myriad cultures of the numerous people of Southern India. -

Maharajas' College, Ernakulam to Launch India's

MAHARAJAS’ COLLEGE, ERNAKULAM TO LAUNCH INDIA’S FIRST CERTIFICATE PROGRAMME ON “INTANGIBLE HERITAGE TOURISM”(CPIHT) 1. Continuous disasters during the past three years, including the Kerala Floods (2018 and 2019) and the current Pandemic Covid 19 (2020), has affected the tourism industry in India. It is under pressure to adapt itself to meet the many new challenges. It is the right time for a paradigm shift in our approach to heritage. We need to look beyond the traditional tangible aspects of heritage towards intangible heritage, with its resilience power and extensive use of the digital medium. 2. At this stage, it is appropriate that, Maharajas' College, Ernakulam, is going to bring under one umbrella the two sectors - Heritage (Intangible) and Tourism - by launching a Certificate Programme on “Intangible Heritage Tourism” (CPIHT)- the first of its kind in India. It offers exposure of students to the fundamental principles of heritage especially intangible heritage as well as tourism with local case studies of resilient heritage and responsible tourism. The fact that Kerala has 4 out of the 13 UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage subscribed from India will be of advantage in this regard. 3. All the activities of the Program will be arranged online, binding to the Covid protocols. The Program consisting of 60 hours will be completed in 6 months. There will be weekly sessions of 4 Hours which will be scheduled on Saturdays. There is no age bar. A Bachelor’s degree from any University in India or abroad approved by UGC is the eligibility for applying. 4.