Translocated Making in Experimental Collaborative Design Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IEPF-2 for 2016-17 DATA UPLOAD in JMCWEBSITE.Xlsx

JMC Projects (India) Ltd. ‐ Statement of Unclaimed amount e.g. Unclaimed Dividend / interest on Deposits etc. as on 10/08/2017 (date of 31st Annual General Meeting) Proposed date Nature of Unclaimed UnclaimedA Name of Investor Address Country State Pincode Folio No. of tranfer to Amount mt. In Rs, IEPF Amount for unclaimed A MALLIKA B 6/2 DIGJAM STAFF COLONY AIR FORCE ROAD JAMNAGAR INDIA GUJARAT 361006 JMC IN30103924585768 80 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed A N GAUR F NO 45, SAAKSHARA APARTMENT, A‐3 PASCHIM VIHAR NEW DELHI INDIA DELHI 110063 JMC 0000000000011962 600 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed A PRABHAKAR RAO 6/6 VINOBA NAGAR SHIMOGA SHIMOGA INDIA KARNATAKA 577201 JMC 1202300000812029 100 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed A RADHA RUKMANI S‐16/5 7‐56 ACRES QUARTERS METTUR DAM SALEM DIST INDIA TAMIL NADU 636401 JMC IN30039412619568 100 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed A SAMSUDEEN NO 39 BAKERS STREET CHOOLAI CHENNAI INDIA TAMIL NADU 600112 JMC 0000000000000135 300 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed A V ISPAT PVT LTD AGAM KUAN INDIA BIHAR 800007 JMC IN30133018956765 5500 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed AARTI MANISH CHANDAK VANSHREE APPTT AKOLA ROAD AKOT INDIA MAHARASHTRA 444101 JMC 1302310000031381 4 01‐Sept‐2018 and unpaid dividend PUTHEN VEETTIL HOUSE CHETTIYARANGADI P O NAMBOORIPOTTY Amount for unclaimed ABDUL GAFUR P V INDIA KERALA 679333 JMC IN30023913104849 20 01‐Sept‐2018 MANIMOOLY MALAPPURAM and unpaid dividend -

OFFICE PROFILE Final 04-07-2017.Pmd

• Profile of Key Persons • Company Activity • Technical & Administrative Setup • Office Setup • List of Projects Ami Engineers, Consulting Engineers 4, First Floor, Shitlam Apartments, Bh. Madhav Complex, Near ATIRA, Dr. V.S. Marg, Ambawadi, Ahmedabad 380 015 Ph. (079) 2630 9417 e-Mail. [email protected] [email protected] O F I C E P R L O F I C E P R L Profile: Prof. R.J. Shah Name RASIK JAGJIVANDAS SHAH Date of Birth 6th November, 1938 Place of Birth Baroda Permanent Address A/1, Kameshwar Apartments, Opp. to Satyanarayan Temple Surendra Mangaldas Road, Near Sneh Kunj Bust Stop, Ahmedabad-380 015 Educational Record • Degree of Bachelor of Civil Engineering from Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda with honours in 1960. • Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering with Concrete Technology and Structural Engineering as major subjects from Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar with honours in 1966 Courses attended • Six weeks full time course in Prestressed Concrete in 1964 at Faculty of Technology & Engineering, Baroda. • Four weeks full time course in Soil Mechanics & Foundation Engineering in 1966 at Indian institute of Technology, Delhi. • Six weeks full time course in Housing in Urban Development conducted with the extension service team of Development Planning Unit, University College, London, at School of Architecture, Ahmedabad. • One week course on Prestressed Concrete Design conducted by Prof. G.S. Ramaswamy at Ahmedabad • One week course on Design of Earthquake Resistant Structures conducted by Dr. Jain & Dr. Murthy of Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur Teaching Assignments • For five years worked as Assistant Lecturer in Structural Engineering Department at BVM Engineering College, Vallabh Vidyangaar. -

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

Unpaid Unclaimed Master 2008-2014

DFM FOODS LIMITED DETAILS OF UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND 2012 - 13 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband First Father/Husband Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Securities Investment Type Amount Due(in Rs.) Proposed Date of transfer Name Middle Name to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) A S SEEHRA BAKSHESH SINGH O-7 New Mahavir Nagar New INDIA Delhi 110018 00002718 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2020 Delhi Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend A K GUPTA S S GUPTA 1433 Maruti Vihar Chakkarpur INDIA Haryana 122001 00011213 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2020 Gurgaon Hr Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend A K JAITLY H R JAITLY A1/6803 East Rohtas Nagar INDIA Delhi 110032 00012509 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2020 Delhi Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend A CHANDRA SEKHARGUPTA A SRINAVASA MRTHY 28/369 Old Town Anantapur Ap INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 00013724 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2020 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend A B ARORA R L ARORA Advocate Dso Compound Court INDIA Uttar Pradesh 247001 00014890 Amount for 250.00 03-OCT-2020 Road Saharan Pur Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend A GUPTA RAM CHANDER C-2/81 Yamuna Vihar Delhi INDIA Delhi 110053 00023027 Amount for 2.50 03-OCT-2020 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend AAKASH SALUJA SANJAY SALUJA 11a D-1/c L I G Flats Janak Puri INDIA Delhi 110058 00022420 Amount for 2.50 03-OCT-2020 New Delhi Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend AARAMBH FINANCE LTD INVESTMENT I-78 West Patel Nagar N Delhi INDIA Delhi 110008 00019346 Amount for 1250.00 03-OCT-2020 Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 03-OCT-2020 AARTI BANSAL KAMAL -

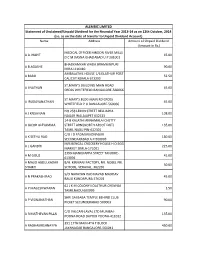

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend

ALEMBIC LIMITED Statement of Unclaimed/Unpaid Dividend for the Financial Year 2013-14 as on 12th October, 2014 (i.e. as on the date of transfer to Unpaid Dividend Account) Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Amount in Rs.) MEDICAL OFFICER HINDON RIVER MILLS A A JHAPIT 45.00 D C M DASNA GHAZIABAD U P 201001 BHADKAMKAR WADA BRAMHINPURI A B AGASHE 90.00 MIRAJ 416410 AMBALATHIL HOUSE 1/6 ELATHUR POST A BABU 52.50 CALICUT KERALA 673303 ST.MARY'S BUILDING MAIN ROAD A I NATHAN 45.00 CROSS WHITEFIELD BANGALORE-560066 ST MARY'S BLDG MAIN RD CROSS A IRUDAYANATHAN 45.00 WHITEFIELD P O BANGALORE-560066 NO 258 LEMIN STREET BELLIAPPA A J KRISHNAN 108.00 NAGAR WALAJAPET 632513 14-B KALATHI ANNAMALAI CHETTY A JACOB ALEYAMMA STREET ARNI(NORTH ARCOT DIST) 135.00 TAMIL NADU PIN-632301 C/O I D PADMARAONAGAR A K SETHU RAO 180.00 SECUNDARABAD A P-500003 M/S BENGAL CROCKERY HOUSE H O EGG A L GANDHI 225.00 MARKET SIMLA-171001 2399 MANOJIAPPA STREET TANJORE- A M GOUZ 45.00 613001 A MAJID ABDULKADAR B/H. KIRMANI FACTORY, NR. NOBEL PRI. 30.00 SHAIKH SCHOOL, VERAVAL. 362265 S/O NARAYAN RAO NAVAD MADHAV A N PRAKASH RAO 45.00 BAUG KUNDAPURA 576201 62 J K M COLONY KOLATHUR CHENNAI A P MAGESHWARAN 1.50 TAMILNADU 600099 SHRI SAI BABA TEMPLE BEHIND CLUB A P VISWANATHAN 90.00 PICKET SECUNDERABAD 500003 C/O VALCAN-LAVAL LTD MUMBAI- A R MATHEVAN PILLAI 135.00 POONA ROAD DAPODI POONA-411012 391 17TH MAIN 4TH T BLOCK A RADHAKRISHNAYYA 450.00 JAYANAGAR BANGALORE-560041 ALEMBIC LIMITED Statement of Unclaimed/Unpaid Dividend for the Financial Year 2013-14 as on 12th October, 2014 (i.e. -

ASC UNPAID 2016-2017 Link 31-03-2019.Xlsx

Ahmedabad Steelcraft Ltd Dividend unpaid details for F Y 2016‐17 DIVIDEN SR NO DD NO DD Date F L NO / CL ID NAME OF SHARE HOLDER Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN SHARES MICRNO ORGDD AMOUNT 1 521808 08/09/2017 1201060001619513 ASHOK GANESH KULKARNI 97, SOMWAR PETH DIST NASIK MALEGAON 423203 70 35.00 521808 521808 2 286210 08/09/2017 1201070000147787 SMITA BHADRESH SHAH 202/A, KRISHNA COMPLEX ANAND MAHEL ROAD RANDER SURAT 395009 200 100.00 3 413429 08/09/2017 1201090000496287 ASWINRAAM V.S. 5/85, MANGANUR PERIYAKADAMPATTI (PO) THARAMANGALAM SALEM 636502 100 50.00 413429 413429 4 521818 08/09/2017 1201090000565012 CHANDRAKANT PARASMAL JAIN NEAR AHILYABI VIHIR NANDURBAR 425412 100 50.00 521818 521818 5 286153 08/09/2017 1201090001545354 ALPESHBHAI JERAMBHAI MANGUKIYA HUF 221/222, KAMALBAUG SOC, AMBAWADI B/H, RAMKRISHNA SOC, L H ROAD SURAT 395006 160 80.00 6 286138 08/09/2017 1201090400008408 MANOJ KUMAR GOEL 256, SADAR BAZAR, LUCKNOW 226002 2300 1150.00 7 286142 08/09/2017 1201090900009209 DIGAMBAR RAMCHANDRA KAJWE 1404, ANGRE HOUSE, DOCKYARD ROAD, MAZGAON MUMBAI 400010 1 0.50 8 521931 08/09/2017 1201750000307504 RAGHUNATH NAYAKWADI .Q NO B‐8/25, PTS NTPC, JYOTHI NAGAR, RAMAGUNDA DIST KARIMNAGAR, DIST KARIMNAGAR, 505215 100 50.00 521931 521931 9 286251 08/09/2017 1201910100848264 ADESH KUMAR GUPTA VIJAY MANDI MURADNAGAR GHAZIABAD 201206 100 50.00 10 286172 08/09/2017 1201910102089581 VIDYA PRAKASH GUPTA 2941/218 VISHRAM NAGAR TRI NAGAR DELHI 110035 100 50.00 11 521779 08/09/2017 1202000000066298 KRISHNARAO PANDURANG CHOPADE YASH APARTMENT FLAT NO. -

ASC UNPAID 2012-2013 Link 31-03-2019.Xlsx

Ahmedabad Steelcraft Ltd Dividend unpaid details for F Y 2012‐13 Dividend SR NO D D No DD DATE F L NO / CL ID NAME OF SHARE HOLDER Address Add2 Add3 City PIN SHARES Amount 1 816054 29/08/2013 1201060001619513 ASHOK GANESH KULKARNI 97, SOMWAR PETH DIST NASIK MALEGAON 423203 70 70.00 2 816458 29/08/2013 1201090000496287 ASWINRAAM V.S. 5/85, MANGANUR PERIYAKADAMPATTI (PO) THARAMANGALAM SALEM 636502 100 100.00 3 814394 29/08/2013 1201210100119492 BHARAT KUMAR BOOB C/O R.B.AGENCIES NR.MAHESHWARI NOHRA,47BAPU RAJENDRA MARG, MASURIA, PAL ROAD JODHPUR 342003 100 100.00 4 814389 29/08/2013 1201210100133247 URMILA TAK 3, ASHOK VIHAR, BHADVASIA, JODHPUR 342001 100 100.00 5 816069 29/08/2013 1201330000672353 MANOJ BATESINGH RAGHUVANSHI BAHER PURA POLICE LANE NANDURBAR 425412 NANDURBAR 425412 100 100.00 6 814553 29/08/2013 1201800000079344 AMRITLAL PARMANAND MARTHAK PARAM ANAND 3 KUBER NAGAR NAVLAKHI ROAD MORBI 363641 600 600.00 7 814353 29/08/2013 1201910100987254 SHAUKIN KHERODIA MANGALWAR CHOURAYA, TEHSIL DUNGLA, CHITTORGARH 312024 100 100.00 8 868593 29/08/2013 1201910102089581 VIDYA PRAKASH GUPTA 2941/218 VISHRAM NAGAR TRI NAGAR DELHI 110035 100 100.00 9 814347 29/08/2013 1202650000007464 SHANTI LAL SONI SADAR BAZAR, NEAR TRIPOLIYA KI POL, JAITARAN,DIST.PALI‐MARWAR JAITARAN 306302 100 100.00 10 815466 29/08/2013 1202680000095743 AMRUTBHAI KUNVARJIBHAI PATEL 302,SHUBH APPARTMENT, OPP.MAHADEV BAGH, . VALLABH VIDYANAGAR 388120 1 1.00 11 815494 29/08/2013 1202890000017710 ANJANABEN SUBHASH SARAIYA 63, ASHIRWAD SOCIETY, GOVINDNAGAR, P.O. DAHOD DAHOD -

Unclaimed FD Int to Transferred to IEPF in FY 2018-19.Xlsx

JMC Projects (India) Limited Unclaimed Fixed Deposit Interest being transferred to Investor Education & Protection Fund (IEPF) FD Int. Amt. Interest due FD Holder Name Address Pincode FD Number Principal Rs. date Amt. Rs. PURNIMABEN CHANDRAKANT 1227/1 CHORAWALO 380001 AHD1000249 14000 385.00 31/12/2011 SHAH KHANCHO TALIYA NI POLE SARANGPUR AHMEDABAD SUREKHA MANISH SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMRCIAL CENTRE 380001 AHD1001714 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 SAKAR BAZAR KALUPUR AHMEDABAD KAVITA VINODBHAI SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMERCIAL 380001 AHD1001715 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 CENTRE, SAKAR BAZAR, KALUPUR AHMEDABAD MANISH MANGILAL SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMERCIAL 380001 AHD1001716 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 CENTRE, SAKAR BAZAR, KALUPUR AHMEDABAD SOHINI DEVIMANGILAL SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMERCIAL 380001 AHD1001717 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 CENTRE, SAKAR BAZAR, KALUPUR AHMEDABAD VINODBHAI MANGILAL SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMERCIAL 380001 AHD1001718 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 CENTRE SAKAR BAZAR, KALUPUR AHMEDABAD VARSHA K DIXIT 546/1, JAYSHRI NIVAS, 380059 AHD1000220 10000 1050.00 31/12/2011 JAYSHRI MAHALAXMI DHAM, B/H THALTEJ GAM AHMEDABAD SHREEDEVI L VAISHNAV E/73 AYOJAN NAGAR SOCIETY, 380007 AHD0700549 10000 225.00 31/12/2011 PALDI AHMEDABAD SUREKHA MANISH SHAH 7‐CLOTH COMMRCIAL CENTRE 380001 AHD1001714 25000 594.00 31/12/2011 SAKAR BAZAR KALUPUR AHMEDABAD JMC Projects (India) Limited Unclaimed Fixed Deposit Interest being transferred to Investor Education & Protection Fund (IEPF) FD Int. Amt. Interest due FD Holder Name Address Pincode FD Number Principal Rs. date Amt. Rs. KAVITA VINODBHAI SHAH 7‐CLOTH -

ASC UNPAID 2015-2016 Link 31-03-2019.Xlsx

Ahmedabad Steelcraft Ltd Dividend unpaid details for F Y 2015‐16 DIVIDEND Sr No DD No DD Date F L NO / CL ID NAME OF SHAREHOLDER Add1 Add2 Add3 City PIN SHARES AMOUNT 1 990803 16/09/2016 1201060001619513 ASHOK GANESH KULKARNI 97, SOMWAR PETH DIST NASIK MALEGAON 423203 70 52.50 2 NECS 16/09/2016 1201070000147787 SMITA BHADRESH SHAH 202/A, KRISHNA COMPLEX ANAND MAHEL ROAD RANDER SURAT 395009 200 150.00 3 991316 16/09/2016 1201090000496287 ASWINRAAM V.S. 5/85, MANGANUR PERIYAKADAMPATTI (PO) THARAMANGALAM SALEM 636502 100 75.00 4 NECS 16/09/2016 1201090000851933 ASHOK KUMAR HARAKCHAND SHAH . 64, MULLA SAHIB STREET, SOWCARPET, CHENNAI 600001 100 75.00 5 NECS 16/09/2016 1201090900009209 DIGAMBAR RAMCHANDRA KAJWE 1404, ANGRE HOUSE, DOCKYARD ROAD, MAZGAON MUMBAI 400010 1 0.75 6 NECS 16/09/2016 1201370000029082 MANJULATA RATANLAL RATANLAL PRAKASHCHANDRA 705/25/4,RANGWALA MARKET SAKAR BAZAR AHMEDABAD 380002 100 75.00 7 990867 16/09/2016 1201750000307504 RAGHUNATH NAYAKWADI .Q NO B‐8/25, PTS NTPC, JYOTHI NAGAR, RAMAGUNDA DIST KARIMNAGAR, DIST KARIMNAGAR, 505215 100 75.00 8 NECS 16/09/2016 1201770100016139 SANGEETA LADHA 13 GOVIND MARG ADARSH NAGAR JAIPUR 302004 100 75.00 9 989897 16/09/2016 1201800000041295 RAMNIKLAL VELJIBHAI GANATRA 45,JANTA SOCIETY NR.RADHIKA CLASSIC JAMNAGAR 361006 200 150.00 10 989775 16/09/2016 1201800000079344 AMRITLAL PARMANAND MARTHAK PARAM ANAND 3 KUBER NAGAR NAVLAKHI ROAD MORBI 363641 600 450.00 11 DR 16/09/2016 1201910100848264 ADESH KUMAR GUPTA VIJAY MANDI MURADNAGAR GHAZIABAD 201206 100 75.00 12 NECS 16/09/2016 1201910102089581 VIDYA PRAKASH GUPTA 2941/218 VISHRAM NAGAR TRI NAGAR DELHI 110035 100 75.00 13 990334 16/09/2016 1202000000066298 KRISHNARAO PANDURANG CHOPADE YASH APARTMENT FLAT NO. -

08 12 Days / 11 Nights Footsteps of Mahatma Gandhi

PROGRAM -08 12 days / 11 Nights Footsteps of Mahatma Gandhi Day 01 - Arrive MUMBAI Upon arrival at International Airport in Mumbai ex Flight (to be advised) in the morning you will be met and assisted at the airport and transferred to your hotel for check-in. Formerly known as Bombay, Mumbai is India’s dream city and often related to New York of India. Mumbai has lots to offer to the modern traveller, from its renowned Bollywood film industry, a fashion epicenter, colonial-era architecture, Gateway of India by waterfront, a home to Asia’s largest slums to the world’s most expensive home. Mumbai, with its Colonial and Art Deco buildings, tall skyscrapers, wild traffic and frenetic pace of life, is one of India’s most intriguing cities. Early afternoon we pickyou from your hotel and take you to visit the famous Mani Bhawan that was the political activity headquarters for father of India ‘Mahatma Gandhi’. Next we visit UNESCO world heritage site Victoria Terminus Train Station built in 1888 & Mumbai Harbor waterfront located bold arch Gateway of India that was built to welcome ‘King George V’ and ‘Queen Mary’ into India. Later explore around the Juhu Chowpati Area or return back to your hotel to relax. Overnight at Hotel in Mumbai Day 02 – Mumbai / Porbandar “Breakfast” Early morning we transfer to Mumbai Airport to connect Flight to Porbandar. Depart Mumbai by Spice Jet Flight SG 2873 (Etd 0925 Hrs) Arrive Porbandar “Economy Class (Eta 1045 Hrs) Check in Baggage 15 Kg per Ticket. On arrival at Porbandar, you will be met by our representative & transfer to hotel (Subject to hotel’s standard check in time). -

PROGRAM -08 12 Days / 11 Nights Footsteps of Mahatma Gandhi

PROGRAM -08 12 days / 11 Nights Footsteps of Mahatma Gandhi Day 01 - Arrive MUMBAI Upon arrival at International Airport in Mumbai ex Flight (to be advised) in the morning you will be met and assisted at the airport and transferred to your hotel for check-in. Formerly known as Bombay, Mumbai is India’s dream city and often related to New York of India. Mumbai has lots to offer to the modern traveller, from its renowned Bollywood film industry, a fashion epicenter, colonial-era architecture, Gateway of India by waterfront, a home to Asia’s largest slums to the world’s most expensive home. Mumbai, with its Colonial and Art Deco buildings, tall skyscrapers, wild traffic and frenetic pace of life, is one of India’s most intriguing cities. Early afternoon we pickyou from your hotel and take you to visit the famous Mani Bhawan that was the political activity headquarters for father of India ‘Mahatma Gandhi’. Next we visit UNESCO world heritage site Victoria Terminus Train Station built in 1888 & Mumbai Harbor waterfront located bold arch Gateway of India that was built to welcome ‘King George V’ and ‘Queen Mary’ into India. Later explore around the Juhu Chowpati Area or return back to your hotel to relax. Overnight at Hotel in Mumbai Day 02 – Mumbai / Porbandar “Breakfast” Early morning we transfer to Mumbai Airport to connect Flight to Porbandar. Depart Mumbai by Spice Jet Flight SG 2873 (Etd 0925 Hrs) Arrive Porbandar “Economy Class (Eta 1045 Hrs) Check in Baggage 15 Kg per Ticket. On arrival at Porbandar, you will be met by our representative & transfer to hotel (Subject to hotel’s standard check in time). -

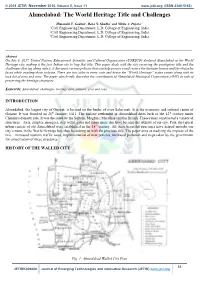

Ahmedabad: the World Heritage Title and Challenges

© 2018 JETIR November 2018, Volume 5, Issue 11 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Ahmedabad: The World Heritage Title and Challenges Himanshi Y. Gadani1, Rena N. Shukla2 and Nikita A. Pujara 3 1Civil Engineering Department, L.D. College of Engineering, India 2Civil Engineering Department, L.D. College of Engineering, India 3Civil Engineering Department, L.D. College of Engineering, India _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract On July 8, 2017, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared Ahmedabad as the World Heritage city, making it the first Indian city to bag that title. This paper deals with the city receiving the prestigious title and the challenges that tag along with it. It discusses various policies that can help preserve and restore the heritage houses and the obstacles faced while availing those policies. There are two sides to every coin and hence the “World Heritage” status comes along with its own list of pros and cons. The paper also briefly describes the contribution of Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) in task of preserving the heritage structures. Keywords: Ahmedabad, challenges, heritage sites, policies, pros and cons. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Ahmedabad, the largest city of Gujarat, is located on the banks of river Sabarmati. It is the economic and cultural center of Gujarat. It was founded on 26th January, 1411. The earliest settlement in Ahmedabad dates back to the 12th century under Chalukya dynasty rule. It was the ruled by the Sultans, Mughals, Marathas and the British. These rulers constructed a variety of structures – forts, temples, mosques, step wells, gates and many more that have become the identity of our city.