Snipe Taxonomy Based on Vocal and Non‐Vocal Sound Displays: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

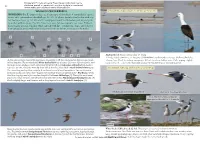

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Rochely Santos Morandini

Rochely Santos Morandini Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para a conservação. (VERSÃO CORRIGIDA – versão original disponível na Biblioteca do IB-USP e na Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações (BDTD) da USP) Functional Diversity of Cerrado birds with a simulation of the loss of open areas and endangered species: implications for conservation. São Paulo 2013 Rochely Santos Morandini Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para a conservação. Functional Diversity of Cerrado birds with a simulation of the loss of open areas and endangered species: implications for conservation. Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ciências, na Área de Ecologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Carlos Motta Junior. São Paulo 2013 Morandini, Rochely Santos Diversidade funcional das aves do Cerrado com simulações da perda de fisionomias campestres e de espécies ameaçadas: implicações para conservação. 112 páginas Dissertação (Mestrado) - Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Ecologia. 1. Aves 2. Cerrado 3. Diversidade Funcional I. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Ecologia Comitê de Acompanhamento: Luís Fábio Silveira Marco Antônio P. L. Batalha Comissão Julgadora: ________________________ ________________________ Prof(a). Dr. Marco Ant ônio Prof(a). Dr. Sergio Tadeu Meirelles Monteiro Granzinolli ____________________________________ Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Carlos Motta Junior Dedicatória A melhor lembrança que tenho da infância são as paisagens de minha terra natal. Dedico este estudo ao Cerrado, com seus troncos retorcidos, seu amanhecer avermelhado, paisagens onde habitam aves tão encantadoras que me tonteiam. -

Genetic Analyses Reveal an Unexpected Refugial Population of Subantarctic Snipe (Coenocorypha Aucklandica)

16 Genetic analyses reveal an unexpected refugial population of subantarctic snipe (Coenocorypha aucklandica) LARA D. SHEPHERD* OLIVER HADDRATH Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Department of Natural History, PO Box 467, Wellington 6140, New Zealand Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada MARIANA BULGARELLA COLIN M. MISKELLY Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington 6140, New Zealand PO Box 467, Wellington 6140, New Zealand School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand ABSTRACT: Auckland Island snipe (Coenocorypha aucklandica aucklandica) are presumed to have occurred throughout the Auckland Island archipelago but became restricted to a subset of the islands following mammal introductions. Snipe were known to have survived on Adams Island, Ewing Island, and Disappointment Island. However, it is uncertain whether snipe were continually present on Enderby Island and/or adjacent Rose Island. These islands lie near Ewing Island, and both hosted a suite of introduced mammals until the last species were eradicated in 1993. Using SNPs generated by ddRAD-Seq we identified four genetically distinct groups of snipe that correspond to the expected three refugia, plus a fourth comprised of Enderby Island and Rose Island. Each genetic group also exhibited private microsatellite alleles. We suggest that snipe survived in situ on Rose and/or Enderby Island in the presence of mammals, and discuss the conservation implications of our findings. Shepherd, L.D.; Bulgarella, M.; Haddrath, O.; Miskelly, C.M. 2020. Genetic analyses reveal an unexpected refugial population of subantarctic snipe (Coenocorypha aucklandica). Notornis 67(1): 403–418. -

Bird Ecology and Conservation in Peru's High Andean Petlands Richard Edward Gibbons Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Bird ecology and conservation in Peru's high Andean petlands Richard Edward Gibbons Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Gibbons, Richard Edward, "Bird ecology and conservation in Peru's high Andean petlands" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2338. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2338 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BIRD ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION IN PERU’S HIGH ANDEAN PEATLANDS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Richard Edward Gibbons B.A., Centenary College of Louisiana, 1995 M.S., Texas A&M University at Corpus Christi, 2004 May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the sacrifice and support of my wife Kimberly Vetter and her family. She will forever have my gratitude and respect for sharing this journey with me. My advisor Dr. J. V. Remsen, Jr. is acknowledged for his incredible knack for identifying the strengths and weaknesses in proposals and manuscripts. His willingness to let me flail about in my search for answers surely has helped make me a better researcher. -

Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns Family SCOLOPACIDAE Rafinesque: Sandpipers and Allies Subfamily GALLINAGININAE Ol

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 191-193. Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns The family sequence of Christidis & Boles (1994), who adopted that of Sibley et al. (1988) and Sibley & Monroe (1990), is followed here. Family SCOLOPACIDAE Rafinesque: Sandpipers and Allies Scolopacea Rafinesque, 1815: Analyse de la Nature: 70 – Type genus Scolopax Linnaeus, 1758. Christidis & Boles (1994) noted that the sequence of genera and species in the Scolopacidae varies considerably between works, and that there are no substantive data to favour any one sequence over another. The sequence adopted by Checklist Committee (1990) is generally followed here in the interests of consistency. Subfamily GALLINAGININAE Olphe-Galliard: Snipes Gallinaginae [sic] Olphe-Galliard, 1891: Contrib. Faune Ornith. Europe Occidentale 14: 18 – Type genus Gallinago Brisson, 1760. Higgins & Davies (1996) and Worthy (2003) are followed here in the use of the subfamily name Gallinagininae for the snipes. The correct spelling of the name is explained by Worthy (2003). Genus Coenocorypha G.R. Gray Coenocorypha G.R. Gray, 1855: Cat. Genera Subgen. Birds Brit. Mus.: 119 – Type species (by original designation) Gallinago aucklandica G.R. Gray. The elevation of Coenocorypha barrierensis, C. iredalei and C. huegeli to species level follows Worthy, Miskelly & Ching (2002). The order in which the species are treated follows that of Holdaway et al. -

Subantarctic Islands Rep 11

THE SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS OF NEW ZEALAND & AUSTRALIA 31 OCTOBER – 18 NOVEMBER 2011 TOUR REPORT LEADER: HANNU JÄNNES. This cruise, which visits the Snares, the Auckland Islands, Macquarie Island, Campbell Island, the Antipodes Islands, the Bounty Islands and the Chatham Islands, provides what must surely be one of the most outstanding seabird experiences possible anywhere on our planet. Anyone interested in seabirds and penguins must do this tour once in their lifetime! During our 18 day voyage we visited a succession of tiny specks of land in the vast Southern Ocean that provided an extraordinary array of penguins, albatrosses, petrels, storm-petrels and shags, as well as some of the world’s rarest landbirds. Throughout our voyage, there was a wonderful feeling of wilderness, so rare these days on our overcrowded planet. Most of the islands that we visited were uninhabited and we hardly saw another ship in all the time we were at sea. On the 2011 tour we recorded 125 bird species, of which 42 were tubenoses including no less than 14 forms of albatrosses, 24 species of shearwaters, petrels and prions, and four species of storm- petrels! On land, we were treated to magical encounters with a variety of breeding penguins (in total a whopping nine species) and albatrosses, plus a selection of the rarest land birds in the World. Trip highlights included close encounters with the Royal, King and Gentoo Penguins on Macquarie Island, face-to-face contact with Southern Royal Albatrosses on Campbell Island, huge numbers of Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses -

Pan-American Shorebird Program Shorebird Marking Protocol

Shorebird Marking Protocol – April 2016 Pan American Shorebird Program Shorebird Marking Protocol - April 2016 - Endorsed by: Shorebird Marking Protocol – April 2016 Lesley-Anne Howes, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, Sophie Béraud, Canadian Wildlife Service, ECCC, Ottawa, ON, Canada, and Véronique Drolet-Gratton, Canadian Wildlife Service, ECCC, Ottawa, ON, Canada. In consultation with: (In alphabetical order) Brad Andres, US Shorebird Conservation Plan, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Lakewood CO USA Yves Aubry, Canadian Wildlife Service, ECCC, Quebec QC, Canada Rúben Dellacasa, Aves Argentinas, BirdLife International en Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina Christian Friis, Canadian Wildlife Service, ECCC, Toronto ON, Canada Nyls de Pracontal, Groupe d’Étude et de Protection des Oiseaux en Guyane (GEPOG), Cayennne, Guyane Cheri Gratto-Trevor, Prairie and Northern Wildlife Research Centre, ECCC, Saskatoon SK, Canada Richard Johnston, Asociación Calidris, Cali, Colombia and CWE, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver BC, Canada Kevin S. Kalasz, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife, DNREC, Smyrna DE, USA Richard Lanctot, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Migratory Bird Management, Anchorage AK, USA Sophie Maille, Groupe d’Étude et de Protection des Oiseaux en Guyane (GEPOG), Cayennne, Guyane David Mizrahi, New Jersey Audubon Society, Cape May Court House NJ, USA Bruce Peterjohn, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel MD, USA Eveling Tavera Fernandez, Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad -

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere

Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM) October 2018 Mike Ausman Citation: Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). 2018. Standards for Monitoring Nonbreeding Shorebirds in the Western Hemisphere. Unpublished report, Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). Available at: https://www.shorebirdplan.org/science/program-for-regional-and- international-shorebird-monitoring/. Primary Authors: Matt Reiter, Chair, PRISM, Point Blue Conservation Science, [email protected]; and Brad A. Andres, National Coordinator U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [email protected]. Acknowledgements Both current and previous members of the PRISM Committee, workshop attendees in Panama City and Colorado, and additional reviewers made this document possible: Asociación Calidris – Diana Eusse, Carlos Ruiz Birdlife International – Isadora Angarita BirdsCaribbean – Lisa Sorensen California Department of Fish and Wildlife – Lara Sparks Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Mark Drever, Christian Friis, Ann McKellar, Julie Paquet, Cynthia Pekarik, Adam Smith; Environment and Climate Change Canada, Science and Technology – Paul Smith Centro de Ornitologia y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) – Fernando Angulo El Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada – Eduardo Palacios Fundación Humedales – Daniel Blanco Manomet – Stephen Brown, Rob Clay, Arne Lesterhuis, Brad Winn Museo Nacional de Costa Rica – Ghisselle Alvarado National Audubon Society – Melanie Driscoll, Matt Jeffery, Maki Tazawa Point Blue Conservation Science – Catherine Hickey, Matt Reiter Quetzalli – Salvadora Morales, Orlando Jarquin Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile (ROC) – Heraldo Norambuena SalvaNatura – Alvaro Moises SAVE Brasil – Juliana Bosi Almeida Simon Fraser University – Richard Johnston Sociedad Audubon de Panamá – Karl Kaufman, Rosabel Miró U.S. -

Brazil I & II Trip Report

North Eastern Brazil I & II Trip Report 20th October to 15th November 2013 Araripe Manakin by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour leaderForrest Rowland NE Brazil I tour Top 10 birds as voted by participants: 1. Lear’s Macaw 2. Araripe Manakin 3. Jandaya Parakeet Trip Report - RBT NE Brazil I & II 2013 2 4. Fringe-backed Fire-eye 5. Great Xenops 6. Seven-coloured Tanager 7. Ash-throated Crake 8. Stripe-backed Antbird 9. Scarlet-throated Tanager 10. Blue-winged Macaw NE Brazil II tour Top 10 as voted by participants: 1. Ochre-rumped Antbird 2. Giant Snipe 3. Ruby-topaz Hummingbird (Ruby Topaz) 4. Hooded Visorbearer 5. Slender Antbird 6. Collared Crescentchest 7. White-collared Foliage-Gleaner 8. White-eared Puffbird 9. Masked Duck 10. Pygmy Nightjar NE Brazil is finally gaining the notoriety it deserves among wildlife enthusiasts, nature lovers, and, of course, birders! The variety of habitats that its vast borders encompass, hosting more than 600 bird species (including over 100 endemics), range from lush coastal rainforests, to xerophytic desert-like scrub in the north, across the vast cerrado full of microhabitats both known as well as entirely unexplored. This incredible diversity, combined with emerging infrastructure, a burgeoning economy paying more attention to eco-tourism, and a vibrant, dynamic culture makes NE Brazil one of the planet’s most unique and rewarding destinations to explore. The various destinations we visited on these tours allowed us time in all of these diverse habitat types – and some in the Lear’s Macaws by Forrest Rowland most spectacular fashion! Our List Totals of 501 birds and 15 species of mammals (including such specials as Lear’s Macaw, Araripe Manakin, Bahia Tapaculo, and Pink-legged Graveteiro) reflect not only how diverse the region is, but just how rich it can be from day to day. -

Falkland Islands Species List

Falkland Islands Species List Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 BIRDS* 2 DUCKS, GEESE, & WATERFOWL Anseriformes - Anatidae 3 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus 4 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba 5 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta 6 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida 7 Ruddy-headed Goose Chloephaga rubidiceps 8 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus 9 Falkland Steamer-Duck Tachyeres brachypterus 10 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides 11 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix 12 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 13 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera 14 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica 15 Silver Teal Anas versicolor 16 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris 17 GREBES Podicipediformes - Podicipedidae 18 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland 19 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis 20 PENGUINS Sphenisciformes - Spheniscidae 21 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus 22 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua Cheesemans' Ecology Safaris Species List Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 11 Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 23 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus 24 Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus 25 Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome 26 ALBATROSSES Procellariiformes - Diomedeidae 27 Gray-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma 28 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris 29 Royal Albatross (Southern) Diomedea epomophora epomophora 30 Royal Albatross (Northern) Diomedea epomophora sanfordi 31 Wandering Albatross (Snowy) Diomedea exulans exulans 32 Wandering