Teamster Rebellion.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

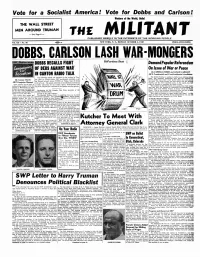

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Verizon Strikers Stand up to Attacks on Their Unions

AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.50 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Capitalism turns Ecuador quake into a social disaster — PAGE 8 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 80/NO. 18 MAY 9, 2016 Washington, Verizon strikers stand up ‘Workers, Moscow seek to attacks on their unions unions need to impose new Workers rally, answer bosses’ propaganda to control Mideast ‘order’ job safety’ BY MAGGIE TROWE BY JOHN STUDER Washington and Moscow are scram- “My job at Verizon has gotten more bling to hold together an agreement dangerous. I’ve been electrocuted to impose some stability and order in twice on the job, once while they Syria and the broader Mideast region. made me work by myself,” John Hop- But the competing interests of differ- ent ruling classes and factions, includ- Socialist Workers Party ing between the U.S. and Russian gov- ernments themselves, keep getting in candidates speak out the way. Millions of workers and farm- ers in the region pay a terrible price for per, a 25-year outside field technician the ongoing bloodshed. from Rockland County, New York, Talks on ending the five-year war told Socialist Workers Party presi- in Syria hit a stumbling block when dential candidate Alyson Kennedy forces opposing the regime of Presi- and campaign supporter Tony Lane as dent Bashar al-Assad declared a pause they joined a strike rally in Trenton, in their participation April 18. They New Jersey, April 25. “You put your accused the Syrian government of life on the line but the company is un- refusing to end hostilities or to allow CWA District 2-13 grateful.” Strikers and supporters picket Philadelphia Verizon store April 22. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

Oral History Transcript T-0217, Interview with David Burbank

ORAL HISTORY T-0217 INTERVIEW WITH DAVID BURBANK INTERVIEWED BY NOEL DARK SOCIALIST PARTY PROJECT NOVEMBER 29, 1972 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. My name is Noel Clark. I am a graduate student at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. The date is November 29, 1972. I am going to talk this evening to Mr. David Burbank about the Socialist Party in the State of Missouri. CLARK: Mr. Burbank, would you mind, first of all, saying your name? BURBANK: Yes, I am David Burbank. CLARK: ...and your address. BURBANK: My address is 300 Mansion Center, St. Louis. CLARK: Okay. Mr. Burbank, would you mind giving us a short history on the Socialist Party as you first became acquainted with it? BURBANK: Well, I think I might start out by giving a little bit of background. As you probably know, the Socialist Party was greatly reduced after World War I. The Red scares and the Communist split reduced it nationally to very little. There were several cities where they had originally been very strong before World War I and even during World War I. St. Louis was one of them. There was a very large German population and this party here was, to a very large extent, a German organization. It had been so for a long time. The German Socialists were active in various German Unions, like the brewery works, the carpenters, machinists and so on, and exercised considerable influence in these unions. -

Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft

Workers of the World, Unite! SPECIAL SWP CONVENTION ISSUE THE MILITANT __________ PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE __________________ Vol. XII— No. 28 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JULY 12, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS AND CARLSON ADDRESS NATION IN BROADCASTS FROM SWP CONVENTION Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft. SWP Candidates Address the Nation Inspiring Five-Day Gathering The Two Opens Presidential Campaign A m e rica s Of Socialist Workers Party By Art Preis James P. Cannon’s Key-Note Speech . NEW YORK, July 6 — Cheering to the echo the choice of Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson as first Over the ABC Network on July 1st Trotskyist candidates for U. S. President and Vice* President, the 13th National Convention of the So The following is the keynote speech delivered by James cialist Workers Party sum-® Cannon, National Secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, a propaganda blow been struck to the party’s 13th convention at 11:15 P. M. on July 1, and moiled the American peo in this country for the socialist broadcast over Radio network ABC at that time. ple to join with the SWP cause. That millions of people in a forward march to a Workers heard the SWP call is shown by Comrade Chairman, Delegates and Friends: and Farmers Government and the flood of letters and postcards We meet in National Convention at a t'ime of the gravest socialism. that hit the SWP National Head quarters in the first post-holiday world crisis— a crisis which contains the direct threat of a third Ih' an atmosphere charged with mail deliveries this morning. -

The Cut and Thrust: the Power of Political Debate in the Films of Ken Loach Author(S): Graham Fuller Source: Cinéaste , Fall 2015, Vol

The Cut and Thrust: The Power of Political Debate in the Films of Ken Loach Author(s): Graham Fuller Source: Cinéaste , Fall 2015, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Fall 2015), pp. 30-35 Published by: Cineaste Publishers, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/26356460 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Cineaste Publishers, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinéaste This content downloaded from 95.183.184.51 on Fri, 07 Aug 2020 09:43:32 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Cut and Thrust The Power of Political Debate in the Films of Ken Loach by GrahamGraham Fuller Fuller resistance—most notably in The Wind That he was by the language of the communist a footnote to history: the story of the Shakes the Barley and the Allen-scripted Span books and leaflets a militant guest had sent Ken Loach's selfless attempt new offilm, the communist Jimmy's Hall, is ish Civil War film Land and Freedom (2005)— him. When the aristocratic pit owner John agitator James Gralton (1886-1945) and his has proved unavoidable. In contradistinction Pritchard (Edward Underdown) calls in fellow County Leitrim villagers to run a to the hyperbolic sequences of glorified may troops to harass the miners and their families dance hall and community center in the face hem and murder synonymous with Holly into submission, however, Joel and Ben find of anti-red paranoia and the puritanical wood cinema, talk is action in Loach's films. -

Lenin and the Bourgeois Press

REQUEST TO READERS Progress Publishers would be glad to have your opinion of this book, its translation and design and any suggestions you may have for future publications. Please send your comments to 17, Zubovsky Boulevard, Moscow, U.S,S.R. Boris Baluyev AND TBE BOURGEOIS PRESS Progress Publishers Moscow Translated from the Russian by James Riordan Designed by Yuri Davydov 6opac 6aJiyee JIEHMH IlOJIEMl1311PYET C 6YJ>)l(YA3HO'A IlPECCO'A Ha Qlj2J1UUCKOM 11301Ke © IlOJIHTH3L(aT, 1977 English translation © Progress Publishers 1983 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 0102020000-346 _ E 32 83 014(01)-83 Contents Introduction . 5 "Highly Interesting-from the Negative Aspect" 8 "Capitalism and the Press" . 23 "For Lack of a Clean Principled Weapon They Snatch at a Dirty One" . 53 "I Would Rather Let Myself Be Drawn and Quartered... " 71 "A Socialist Paper Must Carry on Polemics" 84 "But What Do These Facts Mean?" . 98 "All Praise to You, Writers for Rech and Duma!" 106 "Our Strength Lies in Stating the Truth!" 120 "The Despicable Kind of Trick People Who Have Been Ordered to Raise a Cheer Would Use" . 141 "The Innumerable Vassal Organs of Russian Liberalism" 161 "This Appeared Not in Novoye Vremya, but in a Paper That Calls Itself a Workers' Newspaper" . 184 ··one Chorus. One Orchestra·· 201 INTRODUCTION The polemical writings of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin continue to set an unsurpassed standard of excellence for journalists and all representatives of the progressive press. They teach ideo logical consistency and develop the ability to link political issues of the moment to Marxist philosophical theory. -

Informe De Cuba Contra El Bloqueo Julio 2019 2019 Julio Bloqueo Cuba Contra El Informe De 135 / Conclusions

CONTENIDO CONTENT TABLE DES MATIÈRES 5 / INTRODUCCIÓN 55 / INTRODUCTION 97 / INTRODUCTION 8 / 1. CONTINUIDAD Y RECRUDECIMIENTO 57 / 1. CONTINUITY AND THE TIGHTENING OF 99 / 1. POURSUITE ET DURCISSEMENT DE LA DE LA POLÍTICA DEL BLOQUEO THE BLOCKADE POLICY POLITIQUE DE BLOCUS 1.1 Vigencia de las leyes del bloqueo 1.1 Validity of the laws of the blockade 1.1 Maintien des lois du blocus 10 / 1.2 Principales medidas del bloqueo adoptadas a 58 / 1.2 Principal blockade measures adopted as of June 100 / 1.2 Principales mesures de blocus adoptées partir de junio de 2018 2018 depuis juin 2018 13 / 1.3 Aplicación de la Ley Helms-Burton 61 / 1.3 Application of the Helms-Burton Act 103 / 1.3 Application de la Loi Helms-Burton 16 / 2. EL BLOQUEO VIOLA LOS DERECHOS DEL 64 / 2. EL BLOCKADE VIOLATES THE RIGHTS 106 / 2. LE BLOCUS VIOLE LES DROITS DU PUEBLO CUBANO OF THE CUBAN PEOPLE PEUPLE CUBAIN 2.1 Afectaciones a los sectores de mayor impacto 2.1 Repercussions on sectors having the greatest 2.1 Préjudices causés aux secteurs à plus forte social social impact incidence sociale 23 / 2.2 Afectaciones al desarrollo económico 70 / 2.2 Repercussions on economic growth 112 / 2.2 Préjudices causés au développement économique 29 / 3. AFECTACIONES AL SECTOR EXTERNO DE 75 / 3. REPERCUSSSIONS ON THE FOREIGN LA ECONOMÍA CUBANA SECTOR OF THE CUBAN ECONOMY 117 / 3. PRÉJUDICES CAUSÉS AU SECTEUR EXTÉRIEUR DE L’ÉCONOMIE 3.1 Afectaciones al comercio exterior 3.1 Repercussions on foreign trade CUBAINE 32 / 3.2 Afectaciones a las Finanzas 76 / 3.2 Repercussions on finance 3.1 Préjudices causés au commerce extérieur 35 / 4. -

A Socialist Schism

A Socialist Schism: British socialists' reaction to the downfall of Milošević by Andrew Michael William Cragg Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Marsha Siefert Second Reader: Professor Vladimir Petrović CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This work charts the contemporary history of the socialist press in Britain, investigating its coverage of world events in the aftermath of the fall of state socialism. In order to do this, two case studies are considered: firstly, the seventy-eight day NATO bombing campaign over the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1999, and secondly, the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević in October of 2000. The British socialist press analysis is focused on the Morning Star, the only English-language socialist daily newspaper in the world, and the multiple publications affiliated to minor British socialist parties such as the Socialist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Provisional Central Committee). The thesis outlines a broad history of the British socialist movement and its media, before moving on to consider the case studies in detail. -

Support the Socialist Alternative in 1992!

• AUSTRALIA $2.00 • BELGIUM BF60 • CANADA $2.00 • FRANCE FF1 0 • ICELAND Kr150 • NEW ZEALAND $2.50 • SWEDEN Kr1 0 • UK £1.00 • U.S. $1 .50 INSIDE Socialist candidate arrested at Peoria Caterpillar rally THE - PAGE 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 56/ NO. 14 April 10. 1992 Defend Support the socialist abortion alternative in 1992! rights! Tens of thousands of supporters of abor Warren and DeBates campaign against tion rights will be marching in the streets of Washington. D.C.. April 5. This demonstra tion will be an important countermobilization two parties of war, racism, depression to the unrelenting attacks by the government BY GREG McCARTAN WASHINGTON. D.C. - The Socialist EDITORIAL Workers Party candidates for U.S. president and vice-president. James Warren and Es and right-wing forces against a woman's telle DeBates, kicked off their campaign at right to choose. a national press conference here March 31. The Jan. 22, 1973, Supreme Court de The two candidates said they will join c ision legalizing abortion was a historic victory for the rights of women. Be fore supporters across the country for the next the Roe v. Wade decree abortion was ille eight months campaigning to present a so cialist alternative, raise an internationalist gal in most states. Thousands of women and working-class voice, and build the fight were made to bear children against their against the increasingly reactionary course will or forced into an illegal and danger ous back-alley abortion. of the two parties of big business - the Democrats and Republicans. -

Contras Shot Ben Linder 'At Point-Blank Range'

Come to Young Socialist convention .. 3 THE Socialists' brief against gov't spy f"IIes 10 Garment workers discuss Nicaragua 15 . A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING· PEOPLE VOL. 51/NO. 18 MAY 15, 1987 75 CENTS 1\farroquin wms• • Contras shot Ben Linder 'amnesty' 'at point-blank range' .work permit Brother urges Father details BY HARRY RING NEW YORK -In an important gain for democratic rights, Hector Marroquin, a volu-nteers U.S.-organized Mexican-born socialist, was granted a six month work authorization card while his to Nicaragua murder application for residence here is processed under the "amnesty" provision of the new BY HARVEY McARTHUR BY HARVEY McARTHUR Immigration Reform and Control Act. MANAGUA, Nicaragua - "We will MANAGUA, Nicaragua - U.S. en For the past decade, the government has tell the truth in every corner of the United gineer Ben Linder was executed by Wash prevented Marroquin from working .and States," declared John Linder, brother of ington's contra terrorists as he lay wounded has been trying to deport him because of Ben Linder, the U.S. engineer murdered from a grenade attack, the Linder family his membership in the Socialist Workers by ciA-trai,ned contras while building a told a news conference here May 5. Party. hydroelectric facility in northern Nicara Pledging to speak out throughout the Marroquin said he was "jubilant" at re- · gua. United States against the U.S.-organized · ceiving the work authorization and de "Everything the U.S. government has contra war, the family reported new details clared it represented a significant gain in told us about Nicaragua is a lie," John Lin of Linder's murder.