College Graduation As an Entrance Requirement To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Alvin Jones

Volume 71 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 71, 1966-1967 1-1-1967 Charles Alvin Jones Benjamin R. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Benjamin R. Jones, Charles Alvin Jones, 71 DICK. L. REV. 160 (1967). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol71/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES ALVIN JONES By THE HONORABLE BENJAMIN R. JONES* Upon the retirement of Charles Alvin Jones on July 31, 1961, as the thirty-fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the history of our Commonwealth, the Honorable Horace Stern, his colleague for a period of eleven years and the thirty-fourth Chief Justice, then said: "To be sure it will not be an easy task to measure up to the standard set by CHARLES ALVIN JONES and to equal his per- formance of the duties of Chief Justice, because we all know that no Chief Justice served in that capacity with greater dignity, abil- ity, scholarly attainments, and overall kindliness than Chief Jus- tice JONES, thereby winning for himself the profound respect, admiration and affection not only of the members of the bar but for all people of the Commonwealth." Such tribute succinctly and accurately sums up the career of this splendid jurist. As a lawyer and, later, as a nisi prius judge, I, of course, was familiar with the work and opinions of Charles Alvin Jones as a member of the federal and the state appellate judiciaries; unfor- tunately, until the last decade of his life and after I had become his colleague on the bench, I did not come to know him as a person. -

Charles Alvin Jones

Volume 71 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 71, 1966-1967 1-1-1967 Charles Alvin Jones John B. Hannum Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation John B. Hannum, Charles Alvin Jones, 71 DICK. L. REV. 159 (1967). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol71/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES ALVIN JONES* Charles Alvin Jones, Dickinson School of Law, LL.B., 1910, and a Trustee from June, 1945 to 1966, was born at Newport on the banks of the Juniata River in Perry County. He attended local public schools, Mercersburg Academy and Williams College. Sub- sequently he received several honorary degrees from institutions of higher learning. He was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1910, and was associated in practice with Patterson, Sterrett and Acheson in Pittsburgh. For a number of years he served as County Solicitor of Allegheny County. In 1917, before the United States had entered the First World War, he volunteered for Ambulance service with the French Army and was cited for heroism under fnre. In 1918, he transferred to the aviation branch of the United States Navy and was commis- sioned Ensign, U.S.N.R. He practiced law in Pittsburgh following the war as a partner with his previous firm, practicing under the name Sterrett, Acheson and Jones. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXIII October 2009 NO. 4 A LOOKING-GLASS FOR PRESBYTERIANS:RECASTING A PREJUDICE IN LATE COLONIAL PENNSYLVANIA Benjamin Bankhurst 317 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS POLITICAL INFLUENCE IN PHILADELPHIA JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS:ABRAHAM L. FREEDMAN’S ACCOUNT Isador Kranzel, with Eric Klinek 349 ELIZABETH KIRKBRIDE GURNEY’S CORRESPONDENCE WITH ABRAHAM LINCOLN:THE QUAKER DILEMMA Max L. Carter 389 A ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION OF GARY NASH’S THE URBAN CRUCIBLE John M. Murrin, Benjamin L. Carp, Billy G. Smith, Simon Middleton, Richard S. Newman, and Gary B. Nash 397 BOOK REVIEWS 441 INDEX 457 BOOK REVIEWS ROEBER, ed., Ethnographies and Exchanges: Native Americans, Moravians, and Catholics in Early North America, by Richard W. Pointer 441 LEMAY, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 3, Soldier, Scientist, and Politician, 1748–1757, by Barbara Oberg 442 LOANE, Following the Drum: Women at the Valley Forge Encampment, by Holly A. Mayer 444 FALK, Architecture and Artifacts of the Pennsylvania Germans: Constructing Identity in Early America, by Robert St. George 445 WENGER, A Country Storekeeper in Pennsylvania: Creating Economic Networks in Early America, 1790–1807, by Paul G. E. Clemens 447 VARON, Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859, by Judith Giesberg 448 SILBER, Gender and the Sectional Conflict, by Susan Hanket Brandt 450 ARONSON, Nickelodeon City: Pittsburgh at the Movies, 1905–1929, by David Nasaw 451 The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, from 2006 to the present, is now available online to members and subscribers at The History Cooperative, http://www.historycooperative.org. In order to access the full text of articles and reviews, subscribers will need to register for the first time using the identification number on their mailing label. -

1959 Journal

: I OCTOBER TERM, 1959 STATISTICS Original Appellate Miscella- Total neous Number of cases on dockets 12 1,047 1, 119 2, 178 Cases disposed of 0 860 962 1,822 Remaining on dockets. 12 187 157 356 Cases, disposed of—Appellate Docket: By written opinions 110 By per curiam opinions or orders 101 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merits cases) 4 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 645 Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket By written opinions 0 By per curiam opinions or orders 21 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 743 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 146 By dismissal of appeals 17 By transfer to Appellate Docket 35 Number of written opinions 99 Number of printed per curiam opinions 20 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 122 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 24 Number of admissions to bar 3,495 REFERENCE INDEX Page Court convened October 5, 1959, and adjourned June 27, 1960. Reed, J., Designated and assigned to U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 36 Designated and assigned to U.S. Court of Claims 90 Burton, J., Designated and assigned to U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 36 Format of Order List aud Journal changed, October 12, 1960_ _ 3 Court met at 11 :00 a.m. (Argument of Steel Case) (504) _ _ _ , _ 68, 69 Conferences to convene at 10:00 a.m., rather than 11:00 a.m., with luncheon recess at 12:30 p.m. -

Law Alumni Journal: Governor Shafer Addresses Law Alumni Day Gath

et al.: Law Alumni Journal: Governor Shafer addresses Law Alumni Day Gath Published by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, 2014 1 Penn Law Journal, Vol. 2, Iss. 3 [2014], Art. 1 LAW ALUMNI DAY APRIL 27 <law Alumni Journal VOLUME II, NUMBER 3 SPRING 1967 Acting Editor: TABLE OF CONTENTS James D. Evans, Jr. Design Consultant: ADDRESS PRESENTED AT ANNUAL MEETING OF Louis DeV. Day, Jr. UNVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LAW SCHOOL ALUMNI Alumni Advisory Committee: Robert V. Massey, '31 By Governor Raymond P. Shafer 1 J. Barton Harrison, '56 LAW ALUMNI DAY-APRIL 27, 1967 4 The Law Alumni Journal is published three times a year by the Law Alumni FLORIDA ALUMNUS ENDOWS Society of the University of Pennsylvania RARE BOOK ROOM 9 for the information of its members. SHARSWOOD WINS KEEDY TROPHY 10 Please address all communications and manuscripts to: BENJAMIN H. OEHLERT, JR. CHOSEN NEW The Editor PAKISTAN AMBASSADOR 11 Law Alumni Journal University of Pennsylvania COMMISSIONER OF REVENUE SHELDON Law School COHEN SPEAKS AT LAW SCHOOL 11 Thirty-fourth and Chestnut Streets Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 FAN MAIL FOR THE PRISON RESEARCH COUNCIL 12 A VINTAGE YEAR FOR CLASS REUNIONS 12 Cover: Governor Shafer addresses Law Alumni Day Gathering. OWEN J. ROBERTS MEMORIAL LECTURE AND ANNUAL ORDER OF THE COIF DINNER 13 PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS FIFTIETH REUNION HELD 14 Frank Ross cover, page 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 14, 15 U.P.L. INSTITUTE HOLDS MEETING AT Sydney L. Weintraub page 9 LAW SCHOOL MAY 20 14 Fabian Bachrach page 11 GRADUATION-MAY 22, 1967 14 Printed at the University of Pennsylvania printing office. -

NEW TROOP Activities on GERMANY's BORDER CREATES

AVEKAOE DAILT CnCTLATION for the Month of April, 1888 6,124 Member of tba Audit Bnreao of Clrenlatkms MANCHESTER — A CITY OF VILLAGE CHARM VOL. LVII., NO. 200 (O sssUled Advertising on Page 10) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, MAY 24,1938 (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS Sec. Ickes Married NEW TROOP ACTIVITiES MAYOR HAYES BOOED In Dublin; The News ^ ON GERMANY’S BORDER A Surprise to Friends BY STREET CROWDS: Very Few in Washingrton Knew He Was Out of CREATES CRISIS TODAY the Country Until His Cable Messagre NEW TRIAL DATE SET Arrived—Wife a Resident Parley Between Henldn And of Milwaukee. Henlein in Gesture Toward British Mothers at Carroll Murder Trial Jeers In Streets As He Anff- A- Czech Premier Is Ended Waahlngton. May 24 — (api — ?Fe. N. M., August 81. 1935, They Harold L. Ickes, secretary of the In- "’f e married In 1911. Associates Leave Coort- terior, surprised the capital today ; (®Kes, who works mostly In hls Suddenly As The Nazi by cabling coat sleeves and is known for hls from Dublin, Ireland, blunt speech, appeared last in pub- that he had Just been married. room After Judge Sett Leader Leaves The Capital lic before a Senate appropriations The cabinet officer, 64 years old, .sub-committee on May 16. Two disclosed through hls prMs chief days after that discussion of Presi- June 21 As Date For Trial ^ here that he and Mlsa Jane Dahl- dent Roosevelt's spending and lend- Praha, May 24.—(AP)—Re- man, 25, of Milwaukee, were mar- ports of new troop movements ing program, he sailed for Europe. -

October Term, 1957 Statistics

: I OCTOBER TERM, 1957 STATISTICS Original Appellate Miscella- Total neous Number of cases on dockets. _ _ 13 1, 104 891 2, 008 Cases disposed of 1 967 815 1, 783 Remaining on dockets 12 137 76 225 ^aga Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket : By written opinions 125 By per curiam opinions or orders 168 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 4 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 670 Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket By written opinions 0 By per curiam opinions or orders 16 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 648 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 119 By dismissal of appeals 14 By transfer to Appellate Docket 18 Number of written opinions 104 Number of printed per curiam opinions 13 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 110 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 27 Number of admissions to bar 2, 392 REFERENCE INDEX Court convened October 7, 1957, and adjourned June 30, 1958. Page Frankfurter, J., temporarily assigned to Sixth Circuit 336 Reed, J., appointed Special Master (12 Orig.) 168 ' Designated and assigned to U. S. Court of Claims 52, 100, 317 Designated and assigned to U. S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit 181 Minton, J., designated and assigned to U. S. Court of Claims. _ 85 William P. Rogers, Attorney General presented 55 479690—58 1 : : : II John T. Fey, Announcement of resignation as Clerk effective Page August 14, 1958 321 James R. Browning, Appointed Clerk effective August 15, 1958- 326 Warren Olney III, Appointed Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts 124 Entire day devoted to delivery of opinions (5 cases, 19 pieces) March 31, 1958 205 Court adjourned from Wednesday until Monday due to death in family of Justice 47 Conference Room Sessions 3, 161 National Archives—Clerk authorized to transfer manuscript records and miscellaneous papers filed in cases docketed from 1832 to 1860 191 Rules: General Orders in Bankruptcy Nos. -

SENATE MAY 21 the Committee of the Whole House on the PRIVATE BILLS and RESOLU'iions MESSAGE from the HOUSE State of the Union: Mr

5324 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE MAY 21 the Committee of the Whole House on the PRIVATE BILLS AND RESOLU'IIONS MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE State of the Union: Mr. RANKIN: Committee on World War Unde:r: clause 1 of rule XXII, private A message from the House of Repre Veterans' Legislation. H. R. 6069. A bill to bills and resolutions were introduced sentatives, by Mr. Chaffee, one of its amend section 100 of the Servicemen's Re and severally referred as follows: reading clerks, announced that the House adjustment Act of 1944; without amendment By Mr. FARRINGTON: had passed without amendment the bill (Rept. No. 2076) . Referred to the Committee H. R. 6489. A bill for the relief of Mrs. (S. 1305) to confer jurisdiction on the of the Whole House on the State of the Keum Nyu Park; to the· Committee on Im State of North Dakota over offenses com Union. migration and Naturalization. mitted by or against Indians on the Mr. SABATH: Committee on Rules. House H. R. 6490. A bill for the relief of Mrs. Seiko Devils Lake Indian Reservation. Resolution 625. Resolution providing for the Adachi; to the Committee on Immigration consideration of H. R. 1362, a bill to amend and Naturalization. The message also announced that the the Railroad Ret irement Acts, the R ailroad H. R. 6491. A bill for the relief of Kiy'oichi House had agreed to the report of the Unemployment Insurance Act, and subchap Koide; to the Committee on Immigration committee of conference on the disagree ter B of chapt er 9 of the Internal Revenue and Naturalization. -

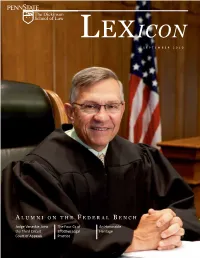

A Lumni on the F Ederal B Ench

LEXICON SEPTEMBER 2010 A LUMNI ON THE F EDERAL B ENCH Judge Vanaskie Joins The Four Cs of An Honorable the Third Circuit Effecve Legal Heritage Court of Appeals Pracce A LETTER FROM THE DEAN I had the good fortune this past May to attend Judge Thomas Vanaskie’s ’78 induction into the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. It was a moving ceremony, with Judge Vanaskie’s wife, Dorothy, and his three adult children at his side, and many Dickinson School of Law students and graduates, and his colleagues watching with pride (including Third Circuit colleague The Honorable D. Brooks Smith ’76, The Honorable William J. Nealon, and almost all of the sit- ting judges of the Middle District of PA!). This issue of our alumni mag- azine—newly anointed as Lexicon—celebrates Judge Vanaskie’s ascension as well as the remarkable contribution of The Dickinson School of Law over the years to our nation’s federal judiciary. The format and name change of the magazine reflect the sugges- tions of a new editorial board composed of Law School graduates, Law School students, and a few Law School faculty. The new name, Lexicon, which is a play on two words that mean an enduring symbol of law, is part of a public relations strategy that responds to the Law School’s growing national and international prominence and audience. We likely will see our national and international audiences grow even larger with the produc- tion of the new public educational television series, World on Trial, which will be filmed in the Apfelbaum Courtroom of the Law School’s Lewis Katz Building. -

The Dean's Letter

Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 5 1957 The Dean's Letter Harold Gill Reuschlein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Harold G. Reuschlein, The Dean's Letter, 2 Vill. L. Rev. 439 (1957). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol2/iss3/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Reuschlein: The Dean's Letter THE DEAN'S LETTER ITH THE OPENING of the current semester, the School of W Law occupied its new home, Garey Hall. And what a thoroughly satisfying home for a law school it is! The building is named for the late Eugene Garey, Esquire, eminent member of the New York Bar and generous benefactor of Villanova. It stands, a solitary ornament, several hundred yards north of the other University buildings on an elevation from which it presents its imposing south wing to the campus. Its graceful lines and generous dimensions will be imposing still, many years from now, when it will be oddly apt to say that Garey Hall is modern. The new building is three stories high and has two-story wings projecting forward on each side. The facade, of cut fieldstone and Indiana limestone, and the pitched slate roofs would appear tradi- tional except for the long ranks of aluminum-mullioned windows. -

The Opinions of Justice and Chief Justice Charles Alvin Jones

Volume 71 Issue 2 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 71, 1966-1967 1-1-1967 The Opinions of Justice and Chief Justice Charles Alvin Jones Laurence H. Eldredge Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Laurence H. Eldredge, The Opinions of Justice and Chief Justice Charles Alvin Jones, 71 DICK. L. REV. 165 (1967). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol71/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OPINIONS OF JUSTICE AND CHIEF JUSTICE CHARLES ALVIN JONES By LAURENCE H. ELDREDGE* When the Honorable Charles Alvin Jones took his seat on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, as the junior associate justice, on January 2, 1945, I looked at him with particular interest because he had already written good appellate court opinions during his five years tenure as a Federal circuit judge. During the following sixteen and one-half years he wrote hundreds of opinions for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania which are reported in fifty-five volumes of the official reports, commencing with 351 Pennsylvania State Reports and ending with volume 405. As they came down on opinion days I received them promptly and studied every one of them. In my capacity as State Reporter for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania I, personally, write the syllabus for every reported decision. Writing a clear, accurate syllabus requires a thorough knowledge of every opinion in the case because concurring and dis- senting opinions frequently bring into sharper focus just what it is that the majority has decided and the areas of agreement and dis- agreement.