Avisuality and Colonialism in the Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

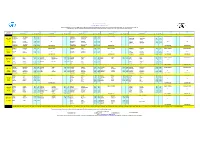

New Unhas Drc Schedule Effect

UNHAS DRC FLIGHT SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE FROM SEPTEMBER 11th 2017 All Planned Flight Times are in LOCAL TIME: Kinshasa, Mbandaka, Brazzaville, Impfondo, Enyelle, Gemena, Libenge, Gbadolite, Zongo, Bangui (UTC + 1); All Other Destinations (UTC + 2) PASSENGERS ARE TO CHECK IN 2 HOURS BEFORE SCHEDULE TIME OF DEPARTURE - PLEASE NOTE THAT THE COUNTER WILL BE CLOSED 1 HOUR BEFORE TIME OF THE DEPARTURE MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY AIRCRAFT DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 7:30 7:45 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 113H MBANDAKA LIBENGE 9:30 10:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 8:45 10:15 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 9:30 10:50 DHC8 LIBENGE ZONGO 11:00 11:20 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 10:45 11:15 GBADOLITE BANGUI 11:20 12:05 5Y-STN ZONGO BANGUI 11:50 12:00 OR IMPFONDO ENYELLE 11:45 12:10 OR BANGUI LIBENGE 13:05 13:25 OR OR BANGUI GBADOLITE 13:00 13:45 ENYELLE MBANDAKA 12:40 13:30 LIBENGE MBANDAKA 13:55 14:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 14:15 15:35 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 14:00 15:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:25 16:55 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:05 17:35 MAINTENANCE BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 16:00 16:15 MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA GOMA 7:15 10:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 213H KANANGA KALEMIE 10:00 11:05 GOMA KALEMIE 12:15 13:05 KANANGA GOMA 10:00 11:25 EMB-135 KALEMIE GOMA 11:45 12:35 OR KALEMIE -

Kiswahili Loanwords in Pazande1

SWAHILI FORUM 27 (2018) KISWAHILI LOANWORDS IN PAZANDE1 CHARLES KUMBATULU HELMA PASCH and Université de Kisangani Universität zu Köln ___________________________________________________________________________ The greater part of Pazande speaking territory is located quite far away from the major swahilophone territories and most speakers of Zande have never been in close contact with speakers of Kiswahili. Only when Tippu Tip reached the north-east of present DR Congo and got a political position of power, the Zande came into contact with Kiswahili. This contact was not intense and there are so few Kiswahili loanwords in Zande, that this has never been a topic of research. The existence of such loanwords is, however, a matter of fact, e.g. kiti 'chair'. Some of the loanwords may have entered the language via Lingala or its variant Bangala. ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Kiswahili, one of the most important languages of the African continent, a vehicular which is used in large areas of East Africa and in the Congo basin, has been in contact with many other languages. It is well known, that the language has borrowed extensively from Arabic, and also from English and other languages. At the same time lexemes from Kiswahili, including words of Arabic origin (Baldi 2012) have been borrowed by primarily local African languages, which makes Swahili a major distributor of words of different linguistic origins. In given cases it may be difficult to decide whether a given language borrowed a specific loanword directly from Kiswahili or from third language which has functioned as intermediary of transfer. In Pazande2, an Ubangian language spoken in the triangle South Sudan, Central African Republic (CAR) and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), there is a relatively short lists of words which are also found in Kiswahili. -

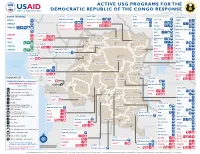

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’

paper 50 From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) by Björn Aust and Willem Jaspers Published by ©BICC, Bonn 2006 Bonn International Center for Conversion Director: Peter J. Croll An der Elisabethkirche 25 D-53113 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-911960 Fax: +49-228-241215 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bicc.de Cover Photo: Willem Jaspers From Resource War to ‘Violent Peace’ Table of contents Summary 4 List of Acronyms 6 Introduction 8 War and war economy in the DRC (1998–2002) 10 Post-war economy and transition in the DRC 12 Aim and structure of the paper 14 1. The Congolese peace process 16 1.1 Power shifts and developments leading to the peace agreement 17 Prologue: Africa’s ‘First World War’ and its war economy 18 Power shifts and the spoils of (formal) peace 24 1.2 Political transition: Structural challenges and spoiler problems 29 Humanitarian Situation and International Assistance 30 ‘Spoiler problems’ and political stalemate in the TNG 34 Systemic Corruption and its Impact on Transition 40 1.3 ‘Violent peace’ and security-related liabilities to transition 56 MONUC and its contribution to peace in the DRC 57 Security-related developments in different parts of the DRC since 2002 60 1.4 Fragility of security sector reform 70 Power struggles between institutions and parallel command structures 76 2. A Tale of two cities: Goma and Bukavu as case studies of the transition in North and South Kivu -

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 -

Unrivalled Art

EN Temporary exhibition UNRIVALLED ART Curator Julien Volper A 109 HOW TO USE THE BOOKLET • The numbers on the showcases match the page numbers in the booklet. - Numbers on top of the showcase refer to the theme. See p. 88 - Numbers on the bottom of the glass panels provide information on objects. See p. 43 • You can also download this booklet using the QR code below or on www.africamuseum.be A MASKS For more than fifty years, a large mask – half human, half animal – was the symbol of this museum. Most Congolese masks take the form of a human or an animal, or a mix of the two. Just as with statues, the style varies from the most breathtaking naturalism, to minimalism, to total abstraction. What we are showing here in the display cases – the faces – is only a part of what the Congolese public could see. The wearers were also dressed in costumes and sometimes carried accessories. Some shook their ankle bells and danced a choreography to the rhythm of the musicians. Isolated from costume and context, these faces on display have lost a large part of their identity. Depending on the culture that a mask belonged to, it performed alone or in company. Some had a precisely defined identity, while others were widely deployed. Most masks had a connection with the world of the dead or with the world of nature spirits. They only performed at important oc- casions or at established ritual moments. In the first half of the 20th century, masks were increasingly used on festive and profane occasions - if they did not entirely disappear from the scene. -

Tippu Tip Overview

Tippu Tip Overview Arab-African Relations The Zanzibar Slave Trade Colonialism But first… Tippu Tip (1837 - 1905) Full name Hamed bin Mohammed el Murjeb Both of his parents were Arab however Hamed was born with dark African features Father was a well established and respected Arab ivory and slave trader Tippu Tip (1837 - 1905) Ambitious from an early age and eager to prove himself to his father and his father’s peers On his first trading trip at age 18 he established a reputation by not revealing his own fatigue Receives the name Tippu Tip because of the onomatopoeic sound of his rifle Tippu Tip (1837 - 1905) Primarily known as a slave trader “Today Tippu Tipp cannot be regarded as a hero since his exploits and gains were at the expense of other human beings” (Farrant 1975) Tippu Tip (1837-1905) “He must however, be regarded as a brave and daring adventurer, a good administrator, and a great leader of men” (Farrant 1975) Tippu Tip (1837 - 1905) Ivory Ivory Ivory!!!! Expanded knowledge of Central Africa Provided safe passage to Europeans through dangerous territories How does it end??? African-Arab Relations: A New Social Order Creation of a new hierarchy of relations - Arab, African converts, Africans Ability to gain status - conversion, concubinage, elite slavery African-Arab Relations: A New Social Order Loyal followers advance Tippu’s expansion Islam used as a method of gaining support Appropriation of culture African-Arab Relations: A New Social Order Tippu’s mother concerned that father would reject an African -

Assessing the Effectiveness of the United Nations Mission

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Thomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 The effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Ivory and Slaves in East and Central Africa (C

Ivory and slaves in East and Central Africa (c. 1800- 1880) Com- Under Central and East Africa we include most of the land north of the Limpopo and Pari' south of the Equator. The coast of what is often called West Central Africa featured in the chapters on the Atlantic slave trade and West Africa, but the peoples and routes that other supplied the slaves for the coast will be discussed here. There are some similarities ports of between the situation in North and West Africa and that existing in East and Central Africa Africa. In Northeast Africa and in the central Sudan of West Africa we come across warlords such as Zubayr and Rabih. In Central and East Africa we meet up with leaders such as Msiri, Mirambo, Tippu Tip and Mlozi who also built up secondary trading and conquest states that dealt in slaves and ivory. In these other regions we witness some empire building during the period of the jihads by people such as al-Hajj Umar and Samory Toure, by Mohammad Ali in Egypt and Menelik in Ethiopia. In this region too, we have some empire building and state expansion, for example on the island of Madagascar by the Merina, in the area of the Great Lakes by Buganda, and also the growth of the trading empire of the Omani Arabs in East Africa. But large empires were scarce because the geography did not encourage the growth of big polities. It was mainly in the Great Lakes region that we find sizeable states such as Buganda. -

Urban Population Map Gis Unit, Monuc 12°E 14°E 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Map No- KINSUB1614 AFRICA URBAN POPULATION MAP GIS UNIT, MONUC 12°E 14°E 16°E 18°E 20°E 22°E 24°E 26°E 28°E 30°E CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN CAMEROON Mobayi-Mbongo Zongo Bosobolo Ango N Gbadolite N ° ° 4 Yakoma 4 Niangara Libenge Bondo Dungu Gemena Mombombo Bambesa Poko Isiro Aketi Bokungu Buta Watsa Aru r e v i Kungu R i g Dimba n a b Binga U Lisala Bumba Mahagi Wamba Nioka N N ° C ° 2 o 2 ng o Djugu R i v Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo Bunia Basankusu Basoko Bafwasende Yahuma Kituku Yangambi Bolomba K ii s a n g a n ii Beni Befale Lubero UGANDA Katwa N M b a n d a k a N ° ° 0 0 Butembo Ingende Ubundu Lake Edward Kayna GABON Bikoro Opala Lubutu Kanyabayonga CONGO Isangi Boende Kirumba Lukolela Rutshuru Ikela Masisi Punia Kiri WalikaleKairenge Monkoto G o m a Inongo S S ° Lake Kivu ° 2 RWANDA 2 Bolobo Lomela Kamisuku Shabunda B u k a v u Walungu Kutu Mushie B a n d u n d u Kamituga Ilebo K ii n d u Oshwe Dekese Lodja BURUNDI Kas Katako-Kombe ai R Uvira iver Lokila Bagata Mangai S Kibombo S ° ° 4 4 K ii n s h a s a Dibaya-Lubwe Budja Fizi Bulungu Kasongo Kasangulu Masi-Manimba Luhatahata Tshela Lubefu Kenge Mweka Kabambare TANZANIA Idiofa Lusambo Mbanza-Ngungu Inkisi ANGOLA Seke-Banza Luebo Lukula Kinzau-Vuete Lubao Kongolo Kikwit Demba Inga Kimpese Boma Popokabaka Gungu M b u j i - M a y i Songololo M b u j i - M a y i Nyunzu S S ° M a tt a d ii ° 6 K a n a n g a 6 K a n a n g a Tshilenge Kabinda Kabalo Muanda Feshi Miabi Kalemie Kazumba Dibaya Katanda Kasongo-Lunda Tshimbulu Lake Tanganyika Tshikapa -

World Bank Document

RESTRICTED Report No. PA-118a Public Disclosure Authorized This report is for official use only by the Bank Group and specifically authorized organizations or persons. It may not be published, quoted or cited without Bank Group authorization. The Rank Group dosnot acenp resnonshibiliy for the ---ray orcr.ltn f th rpot INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENr INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURAL SECTOR SURVEY REPUBLIC OF ZAIRE (in three volumes) VOLUME II Public Disclosure Authorized ANNEXES 1 THROUGH 6 June 19, 1972 Public Disclosure Authorized Aogri niut ulr P =lnt-r DoTpon rtment BACKGROUND DATA US$1 = 0.5 zaires (Z) or i0 ri-La'ruta (1x) One zaire = 2.0 US$ Total Land Area 234.5 million ha (905,000 square miles) of which (i) Forests 102.3 million ha (ii) Cultivated land 2.3 million ha (iii) Permanent pasture 2.3 million ha (iv) Savannahs, mountains, rivers and lakes 127.6 million ha Population (Official estimate, 1970) 21.6 million Distribution: Rural 70% : Urban 30% Annual rate of growth, 1958-70: 3.9% Gross Domestic Product Total, 1970 (est.) Z 1,014 million (US$2,028 million) Per canita. 1970 (est.): Z 47 (US$94) Agricultural output as % of GDP, 1969: 18% Commercialized production: 10% Subsistence production: 8% Agricultural Exports and Imports Value of Agricultural Exports, 1969: US$97 million Share of Total Exports: 14.5% Principal export products: palm oil, coffee, rubber, wood products, tea Value of Agricultural Imports, 1968: US$56 million Share of Total Imports: 11% Principal imports: cereals, fish and fish products, meat and dairy products, fruit and vegetables, tobacco Cnn9u.mpr Prrire Index (IRES - Kinsghaa) June 1970 (June 1960 = 100) 1,454 GENER.AL NOTE ON DATA The statistical data available on most facets of the economy and population of the Republic of Zaire are quite unreliable for the post--Independence periods -- a fact which official publications readily acknowledge. -

WHO/ONCHO/91.166 ~ ENGLISH ONLY (Avec Resume En Fran~Ais)

OISTR. : L1MITEO It'll-~ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 102.3 OISTR. : L1MITEE ~~ .'~ W . I ORGANISATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTE WHO/ONCHO/91.166 ~ ENGLISH ONLY (avec resume en fran~ais) DISTRIBUTION AND PREVALENCE OF ONCHOCERCIASIS AND ITS OCULAR COMPLICATIONS IN ZAIRE AND BURUNDI by A. Fain Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Bruxelles, Belgium CONTENTS 1. Introduction ...•....•........•...•.....................•.•.................. 2. The situation in Zaire ..•.........••.•....•.............•••...•.........••.. 2 3. The situation in Burundi .•.........••.......•...••...•.................•.... 3 4. Summary ................•.•.•.....•.......................................... 3 Resume , .....•..........•.....••....•.....,_................... 4 References .........................................................•............. 4 Table and Map .........•.••..........•..................•..•............•......••. 5 1. INTRODUCTION In 1985, an assessment was made of the distribution and prevalence of human onchocerciasis and its ocular complications in Zaire, Burundi and Rwanda. This assessment was based on data found in the literature or obtained by personal investigations. These data have not as yet been published, except for the global figures for infected or blind people which were given in the report of a WHO Expert Committee on Onchocerciasis (WHO, 1987). Onchocerciasis is still a major public health problem in Zaire and it therefore seemed important to determine exactly the prevailing situation .of this disease in the different