Viewers Respond to a Text Based on Their Own Expectations of It and Predispositions Towards It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

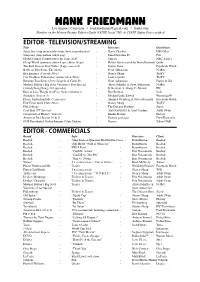

Hank Friedmann CV

HANK FRIEDMANN Los Angeles, California • [email protected] • hankf.com Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (IATSE Local 700) & CSATF Safety Pass certified ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - TELEVISION/STREAMING Title Directors Distributor Santa, Inc (stop motion television show, in production) - Harry Chaskin HBO Max Simpsons (stop motion couch gag) - John Harvatine IV Fox Global Citizen Countdown to the Prize 2020 - Various NBC & Int’l Gloop World (animatic editor 5 eps, editor 15 eps) - Helder Sun (created by Justin Roiland) Quibi The Real Bros of Simi Valley (5 eps, season 3) - Jimmy Tatro Facebook Watch Between Two Ferns: The Movie - Scott Aukerman Netflix Blackspiracy (Comedy Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Can You Beat Yamaneika? (Game Show Pilot) - Lauren Quinn TruTV Between Two Ferns (Jerry Seinfeld & Cardi B.) - Scott Aukerman Funny or Die Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special - Akiva Schaffer & Scott Aukerman Netflix Comedy Bang Bang (110 episodes) - B. Berman, S. Sharp, D. Jelinek IFC How to Lose Weight in 4 Easy Steps (Sundance) - Ben Berman Jash Snatchers (Season 3) - Michael Lukk Litwak Warner/go90 Please Understand Me (5 episodes) - Ahamed Weinberg & Steven Feinartz Facebook Watch End Times Girls Club (Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Flulanthropy - The Director Brothers Seeso Cool Dad (TV Special) - Alex Kavutskiy & Ariel Gardner Adult Swim Crossroads of History “Lincoln” - Marko Slavnic History American Idol Season 10 & 11 - Remote packages Ford/Fremantle GOP Presidential Online Internet Cyber Debate - Various Yahoo!/FoD ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - COMMERCIALS Brand Info Directors Client Reebok - Allen Iverson/Question Mid Double Cross - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - Gigi Hadid “Wild is Wherever” - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - FW19 Trail - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B: Aztrek” - Eric Notarnicola Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B vs. -

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cer�fied Organisa�On)

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cerfied Organisaon) Annual Report 2017-18 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan, Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, (Old Minto Road), New Delhi-110002 Telephone : +91-11-23664147 Fax No:+91-11-23211046 Website:hp://www.trai.gov.in LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To the Central Government through Hon’ble Minister of Communicaons and Informaon Technology It is my privilege to forward the 21st Annual Report for the year 2017-18 of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to be laid before both Houses of Parliament. Included in this Report is the informaon required to be forwarded to the Central Government under the provisions of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997, as amended by TRAI (Amendment) Act, 2000. The Report contains an overview of the telecom and broadcasng sectors and a summary of the key iniaves of TRAI on regulatory maers with specific reference to the funcons mandated to it under the Act. The Audited Annual Statement of Accounts of TRAI is also included in the Report. (RAM SEWAK SHARMA) CHAIRPERSON Dated: September 2018 III TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl.No. Parculars Page Nos. Overview of the Telecom and Broadcasng Sectors 1-8 Policies and Programmes 9-60 A. Review of General Environment in the Telecom Sector Part – I B. Review of Policies and Programmes C. Annexures to Part – I Part – II Review of working and operaon of the Telecom 61-130 Regulatory Authority of India Part – III Funcons of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India in respect of maers 131-150 specified in Secon 11 of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act Part – IV Organizaonal maers of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and 151-220 Financial performance A. -

Return from Exile: How Extreme Metal Culture Found Its Niche with Dethklok and Postnetwork TV

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 27, Issue 2, Pages 163–183 Return from Exile: How Extreme Metal Culture Found Its Niche with Dethklok and Postnetwork TV Joe Tompkins Allegheny College In the premiere episode of Metalocalypse, an original animated series entering its fifth season on the Adult Swim channel,1 300, 000 metalheads travel to the Artic Circle to witness Dethklok, “the world’s greatest cultural force,” as they perform a coffee jingle for the Duncan Hills Coffee Corporation. Despite adverse conditions and a mere single song set list, thousands of fans risk life and limb for the chance to witness the legendary death metal band as they perform a raucous musical ode to the virtues of “ultimate flavor.” As one reporter on the scene observes, “Never before have so many people traveled so far for such a short song.” In a further testament to the band’s outstanding popularity and market value, concertgoers eagerly sign “pain waivers” excusing Dethklok from legal liability in the all too likely event they are somehow “burned, lacerated, eaten alive, poisoned, de-boned, crushed, or hammer-smashed” during the show. Meanwhile, the performance launches the international coffee mogul Duncan Hills to monopoly status, “obliterating” the competition. When asked by news reporters if such an act of corporate sponsorship means that Dethklok is “selling out,” frontman Nathan Explosion growlingly rejoins: “We are here to make coffee metal. We will make everything metal. Blacker than the blackest black . times infinity.” Touting “the biggest -

The Beneficence of Gayface Tim Macausland Western Washington University, [email protected]

Occam's Razor Volume 6 (2016) Article 2 2016 The Beneficence of Gayface Tim MacAusland Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation MacAusland, Tim (2016) "The Beneficence of Gayface," Occam's Razor: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol6/iss1/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacAusland: The Beneficence of Gayface THE BENEFICENCE OF GAYFACE BY TIM MACAUSLAND In 2009, veteran funny man Jim Carrey, best known to the mainstream within the previous decade with for his zany and nearly cartoonish live-action lms like American Beauty and Rent. It was, rather, performances—perhaps none more literally than in that the actors themselves were not gay. However, the 1994 lm e Mask (Russell, 1994)—stretched they never let it show or undermine the believability his comedic boundaries with his portrayal of real- of the roles they played. As expected, the stars life con artist Steven Jay Russell in the lm I Love received much of the acclaim, but the lm does You Phillip Morris (Requa, Ficarra, 2009). Despite represent a peculiar quandary in the ethical value of earning critical success and some of Carrey’s highest straight actors in gay roles. -

Gregg Turkington on What He Learned from Punk Rock

June 13, 2017 - Gregg Turkington is best known for his "anti-comedy" character, Neil Hamburger. The Australian actor co-stars in the film review web series "On Cinema at the Cinema" with Tim Heidecker and is the co-writer and co-star of the Adult Swim series, Decker. He had a part in the 2015 film Ant-Man, and that same year, starred in Entertainment, a drama he co-wrote. In the 1990s, he ran the music label, Amarillo Records, and played in bands like Caroliner, Zip Code Rapists, Faxed Head, and has released a number of albums as Neil Hamburger, mostly on the Chicago independent music label, Drag City. He contributed artwork and live recordings to Flipper's Public Flipper Limited Live 1980-1985. As told to Charlie Sextro, 2383 words. Tags: Culture, Music, Comedy, Inspiration, Beginnings, Independence. Gregg Turkington on what he learned from punk rock I’m interested to hear how your fascination with showmanship began. As a kid, how interested were you in entertainment? Super interested. Initially really with music, and then I got more into movies. I was a complete obsessive about all the things I liked. I grew up in Tempe, Arizona. I was really into Phil Ochs. He was my absolute idol. I was really into the Bee Gees and The Who. Then I got really into a revival, repertoire theater, The Valley Art. It was like $2 or something and I would pretty much go to any movie that was playing, to see what was going on. Then when I saw something that interested me, I would go over to the campus at ASU. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

Well Believes Critic

<curoeip-s., Nabel R. Cillis, 4 California State ' TE Sacramento 9, kiaRAR Senator Savs mors Sign SJS Troubles Spartan Daily I or ON ernight Aren't Unique San Jose State College Next Quarter Says Steel Woes V01.40 SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 12, 1951, No. 53 To Install Booth Are Universal For Registratton San Jose State college "is in 1111 sign-up booth for the Senior the same boat with all of the other 1 (hernight to be held Jan. 11-13 educational institutions in the will he set-up during registration country," as far as the present at the end ol the steel shortage is conc.!' lied. United Min's gym. Cal States Senator William F. Know- Pitts. Overnight committee chalt- land said yesterday !nate announced sesterdav While addressing svnta Clara The iillItlal ellSt to, the, eve'. - county school superintendents on will he a $1 temporal.) ski and officials at the ( ounty 6 dub memhership and $3.77i tor School Department headquar- ters, he added that "the situa- 1 i hose students who will stay at tion is urgent in z alifornia." i he Ilm 'Oki lodge He stated that the -basic prob.) The first SO seniors to sign -lip tern" is that there is nce enough. %%ill Ire quartered at the ( at !ki steel being allocated for educa- lodge at a cost of hli tor the tional purposes. Basically, thi oeekentl. %%Mir the remaining problem will not be solved until 110 seniors o ill sto at the- 11..1,- 1 the defense authorities can Is. i jellei lodge tor 117.5.0. -

Mister America

Presents MISTER AMERICA A film by Eric Notarnicola 86 mins, USA, 2019 Language: English Distribution Mongrel Media Inc 217 – 136 Geary Ave Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filming took place on location in San Bernardino and the Los Angeles area. Using a mix of actors and non-actors, the small crew used documentary techniques to give the experience of a true story unfolding in real time. Often filming in four to five locations a day and using a script in which specific dialogue was scarce but the intention for each scene was detailed, actors improvised fully in the moment to allow their characters to develop naturally. What resulted was a team in-sync and fully ready to capture the chaotic world around them. 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com 1. ABOUT THE CAST As one half of comedy duo “Tim and Eric” and creator of Abso Lutely Productions, Tim Heidecker can easily be viewed as a godfather of subversive, alt-comedy. With roles in “Us”, “Eastbound & Down”, “Awesome Show”, “Portlandia” and more, Mr. Heidecker has helped to affect the comedy landscape for years to come. As a co-creator of On Cinema and its ensuing worlds with Gregg Turkington, he’s been able to prod at multiple facets of society. -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

Loft Film Fest 2015

OCTOBER 21-25, 2015 PRESENTED BY COX COMMUNICATIONS AND DESERT DIAMOND CASINOS & ENTERTAINMENT LOFT FILM FEST 2015 Welcome to the Loft Film Fest! FESTIVAL STAFF I am so proud of the extraordinary lineup of lms and I’m thrilled that we get to bring them to Tucson for ve exciting days in October. festival executive director assistant managers PEGGY JOHNSON RAY BORBOA Film festivals should always be about discovery! I urge you to take some chances KYLE CANFIELD - see a lm that sounds unlike anything you’ve ever seen! Who knows - maybe festival directors PEDRO ROBLES you’ll discover a new director, a fresh face or your new favorite movie! JJ GIDDINGS BRENDA RODRIGUEZ JEFF YANC e 2015 Loft Film Fest will always be remembered as the one where you met volunteer coordinator Rita Moreno, Alfonso Arau, Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana! In addition to managing director BRENDA RODRIGUEZ her many awards, Rita Moreno will be honored at the Kennedy Center Honors in ZACH BRENEMAN December! We’re proud to welcome Larry and Diana back for a 10th anniversary inventory specialist screening of Brokeback Mountain, just after Larry received the National festival programming consultant DAVID CORREA Humanities Medal from President Obama! Alfonso Arau is a Tucson favorite, MIKE PLANTE projectionists because, after all, he is El Guapo in ree Amigos! ANA HUMPHREY associate programmers DALE MEYERS We’re excited to add free outdoor movies this year in our newly improved parking SHAWNA DACOSTA KEISHA RICHARDSON lot! We’re adding valet parking from 5PM during the fest (free for pass holders!) JONATHAN KLEEFELD IZABELLA VANEK For the rst time, select lms will be in competition, a result of e Loft being MIKE WILKINS the only American festival member of the International Confederation of Art art director MATT MCCOY Houses. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

180-TFM153.Feat Btoe

T H E A - Z O F C O M E D Y B Is for... British comedy and the Boat that rocked... ... starring Nick Frost, out of the Wright/Pegg comfort zone and into Richard Curtis' sure-to-be hit comedy. WORDS MATT MUELLER “I don’t like watching comedy,” Even Frost admits it’s as soft-centred and declares Nick Frost. “I know that gooey as Curtis’ previous labours. “What makes me sound like a miserable old else do you expect from bastard but I just don’t.” a Richard Curtis film? This is the most Filling, as he does, the second slot in uncynical, nicest piece of cinema that the comedy A-Z, it’s only natural to you’ll probably see this year. It’s lovely. question the burly funnyman on his own And I managed to watch it without just particular heroes of British comedy during thinking, ‘Oh fuck, I look fat.’” his youth in Essex. “The thing is,” Frost Curtis, an admirer of Hot Fuzz and Shaun continues, “I was a very different person as Of The Dead, wrote the part of cretinous a kid. I only watched slasher pics. When DJ Dave for Frost. “I was tremendously mum and dad were in the pub, they’d let touched,” the actor enthuses. “He’s British me go and hire Halloween or Friday The comedy’s headmaster! And he wrote in a 13th. The first time I remember laughing love scene with Gemma Arterton. Thank like an idiot was The Young Ones. So that you very much, Richard Curtis! We can’t and Blackadder, I guess.” really mention Quantum Of Solace in my And now? “I try not to watch any comedy.