Tax Transparency and the Marketplace: a Pathway to State Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology

SPRING 2016 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW COLLOQUIUM ON TAX POLICY AND PUBLIC FINANCE “The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981” Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology May 3, 2016 Vanderbilt-208 Time: 4:00-5:50 pm Number 14 SCHEDULE FOR 2016 NYU TAX POLICY COLLOQUIUM (All sessions meet on Tuesdays from 4-5:50 pm in Vanderbilt 208, NYU Law School) 1. January 19 – Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. “Corporate Inversions and the unbundling of Regulatory Competition.” 2. January 26 – Michael Simkovic, Seton Hall Law School. “The Knowledge Tax.” 3. February 2 – Lucy Martin, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Political Science. “The Structure of American Income Tax Policy Preferences.” 4. February 9 – Donald Marron, Urban Institute. “Should Governments Tax Unhealthy Foods and Drinks?" 5. February 23 – Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, University of Michigan Law School. “Evaluating BEPS” 6. March 1 – Kevin Markle, University of Iowa Business School. “The Effect of Financial Constraints on Income Shifting by U.S. Multinationals.” 7. March 8 – Theodore P. Seto, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. “Preference-Shifting and the Non-Falsifiability of Optimal Tax Theory.” 8. March 22 – James Kwak, University of Connecticut School of Law. “Reducing Inequality With a Retrospective Tax on Capital.” 9. March 29 – Miranda Stewart, The Australian National University. “Transnational Tax Law: Fiction or Reality, Future or Now?” 10. April 5 – Richard Prisinzano, U.S. Treasury Department, and Danny Yagan, University of California at Berkeley Economics Department, et al. “Business In The United States: Who Owns It And How Much Tax Do They Pay?” 11. -

Economics During the Lincoln Administration

4-15 Economics 1 of 4 A Living Resource Guide to Lincoln's Life and Legacy ECONOMICS DURING THE LINCOLN ADMINISTRATION War Debt . Increased by about $2 million per day by 1862 . Secretary of the Treasury Chase originally sought to finance the war exclusively by borrowing money. The high costs forced him to include taxes in that plan as well. Loans covered about 65% of the war debt. With the help of Jay Cooke, a Philadelphia banker, Chase developed a war bond system that raised $3 billion and saw a quarter of middle class Northerners buying war bonds, setting the precedent that would be followed especially in World War II to finance the war. Morrill Tariff Act (1861) . Proposed by Senator Justin S. Morrill of Vermont to block imported goods . Supported by manufacturers, labor, and some commercial farmers . Brought in about $75 million per year (without the Confederate states, this was little more than had been brought in the 1850s) Revenue Act of 1861 . Restored certain excise tax . Levied a 3% tax on personal incomes higher than $800 per year . Income tax first collected in 1862 . First income tax in U. S. history The Legal Tender Act (1862) . Issued $150 million in treasury notes that came to be called greenbacks . Required that these greenbacks be accepted as legal tender for all debts, public and private (except for interest payments on federal bonds and customs duties) . Investors could buy bonds with greenbacks but acquire gold as interest United States Note (Greenback). EarthLink.net. 18 July 2008 <http://home.earthlink.net/~icepick119/page11.html> Revenue Act of 1862 Office of Curriculum & Instruction/Indiana Department of Education 09/08 This document may be duplicated and distributed as needed. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Contrasting the 1986 Tax Reform Act with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The Promise and Limits of Fundamental Tax Reform: Contrasting the 1986 Tax Reform Act with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Ajay K. Mehrotra†* & Dominic Bayer** In December 2017, the Trump administration and its congressional allies enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, hailing it as the twenty-first century successor to the “landmark” Reagan-era Tax Reform Act of 1986. Indeed, the ’86 Act has long been celebrated by scholars and lawmakers alike as the apex of fundamental tax reform. The ’86 Act’s commitment to broadening the income tax base by eliminating numerous tax benefits and reducing marginal tax rates was seen in 1986 as the culmination of a nearly century- long intellectual movement toward conceptual tax reform. † Copyright © 2019 Ajay K. Mehrotra & Dominic Bayer. * Executive Director & Research Professor, American Bar Foundation; Professor of Law & History, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. An earlier version of this Essay was presented at the 2019 American Association of Law School’s Annual Conference. Many thanks to the participants at that conference for useful feedback, with special thanks for specific comments to Reuven Avi-Yonah, Isaac Martin, Shuyi Oei, Monica Prasad, Dan Shaviro, and Joe Thorndike. And thanks to Clare Gaynor Willis and Robert Owoo for their research assistance and to the editors of the UC Davis Law Review Online, especially Louis Gabriel, for all their help and editorial guidance. ** Leopold Fellow, Nicholas D. Chabraja Center for Historical Studies, Northwestern University Class of 2020. 93 94 UC Davis Law Review Online [Vol. 53:93 While the ’86 Act may have been landmark legislation at its inception, it gradually unraveled over time. -

Farm Bill Workshop & GOVERNMENT Affairs Meeting

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF FARMER COOPERATIVES 2 0 WASHINGTON 1 7 CONFERENCE JUNE 26-28, 2017 HYATT REGENCY WASHINGTON, DC Farm Bill Workshop & GOVERNMENT aFFAIRS mEETING Farm Bill Workshop: Agenda NCFC Washington Conference Farm Bill Workshop Hyatt Regency Hotel Washington, DC June 26, 2017 AGENDA Columbia A/B Room 7:30 AM Registration Open & Breakfast Served 8:00 AM Welcome & Introductions 8:05 AM Balancing Priorities Against a Challenging Baseline Guest Speaker: Jonathan Coppess Clinical Assistant Professor University of Illinois 8:50 AM Crop Insurance & Risk Management Guest Speaker: Tara Smith Torrey & Associates 9:20 AM Priorities for Commodities, Specialty Crops & Livestock Guest Panelist: Sam Willett National Corn Growers Association Reece Langley National Cotton Council Ben Mosely USA Rice Federation John Hollay National Milk Producers Federation Robert Guenther United Fresh Produce Association Bill Davis National Pork Producers Association Representing the Business Interests of Agriculture 10:45 AM Break 11:00 AM Nutrition – Not a slush fund! Guest Speaker: Julian Baer Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry U.S. Senate 11:30 AM Conservation, Energy & Research – Areas for Refocus Guest Panelists: Jason Weller Land O’Lakes, Inc. Former Chief, Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture Bobby Frederick National Grain & Feed Association Josh Maxwell Committee on Agriculture U.S. House of Representatives John Goldberg Science Based Strategies 12:30 PM Lunch 1:00 PM Trade, Rural Development & Credit – Opportunities -

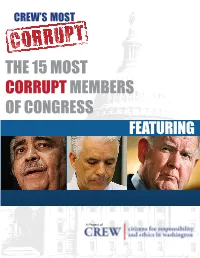

The 15 Most Corrupt Members of Congress Featuring

CREW’S MOST THE 15 MOST CORRUPT MEMBERS OF CONGRESS FEATURING A Project of TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________________________________ Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................1 Methodology....................................................................................................................................2 The Violators A. Members of the House.............................................................................................3 I. Vern Buchanan (R-FL) ...............................................................................4 II. Ken Calvert (R-CA).....................................................................................9 III. Nathan Deal (R-GA)..................................................................................18 IV. Jesse Jackson, Jr. (D-IL)............................................................................24 V. Jerry Lewis (R-CA)...................................................................................27 VI. Alan Mollohan (D-WV).............................................................................44 VII. John Murtha (D-PA)..................................................................................64 VIII. Charles Rangel (D-NY).............................................................................94 IX. Laura Richardson (D-CA).......................................................................110 X. Pete Visclosky -

Entity Classification: the One Hundred-Year Debate

Catholic University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 1995 Article 3 1995 Entity Classification: The One Hundred-Year Debate Patrick E. Hobbs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Patrick E. Hobbs, Entity Classification: The One Hundred-Year Debate, 44 Cath. U. L. Rev. 437 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENTITY CLASSIFICATION: THE ONE HUNDRED-YEAR DEBATE Patrick E. Hobbs* I. Introduction ................................................. 437 II. Evolution of the Tax Definition of the Term "Corporation".. 441 A. The Revenue Act of 1894 ............................... 441 B. The Corporate Excise Tax of 1909 ....................... 452 C. After the Sixteenth Amendment: A Case of Floating Commas and Misplaced Modifiers ....................... 459 D. Developing a Corporate Composite ..................... 468 III. The Failure of the Resemblance Test ........................ 481 A. The Professional Corporation ............................ 481 B. The Limited Partnership ................................. 491 C. The Limited Liability Company .......................... 510 IV . Conclusion .................................................. 518 I. INTRODUCTION One hundred years ago, in the Revenue Act of 1894,1 Congress en- acted our Nation's first peacetime income tax.2 Although the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional within a year of its enactment,3 at least * Associate Professor of Law, Seton Hall University School of Law. B.S., 1982, Se- ton Hall University; J.D., 1985, University of North Carolina; LL.M., 1988, New York Uni- versity. -

Tax Transparency and the Marketplace: a Pathway to State Sustainability

110474 001-130 int NB_43_corr_Ok-Proofs_PG 1_2015-01-09_11:24:08_K Tax Transparency and the Marketplace: A Pathway to State Sustainability Montano Cabezas* This article advances the argument that market to society. It then investigates how more diffuse participants, increasingly concerned about the measurements based on externality assessment 2014 CanLIIDocs 108 sustainability of the social benefits and oppor- could be used to “score” a company’s contribu- tunities derived from the state, are interested tion to society, and how such scoring could affect in how companies contribute to society via both the markets and tax policy. The article con- taxation. The article advocates that companies cludes by reiterating aspirations for tax transpar- should disclose their tax returns for each juris- ency, and by advocating for a new state-business diction in which they operate, in order to give tax paradigm in order to ensure the continued market participants a tool to better understand a viability of the state as a provider of social goods. company’s comprehensive economic contribution L’auteur avance que les acteurs économiques, façon dont la diffusion de mesures tenant de plus en plus préoccupés par la durabilité des compte des externalités peut aider les entreprises opportunités et des avantages sociaux fournis par à évaluer leur contribution sociétale ainsi que l’État, s’intéressent à la façon dont les entreprises l’impact d’une telle diffusion sur les marchés contribuent financièrement à la société grâce et sur la politique fiscale. L’auteur conclut en à l’impôt. L’auteur suggère que les entreprises réitérant ses aspirations pour des politiques devraient divulguer leurs déclarations de fiscales transparentes et en plaidant en faveur revenus dans chacune des juridictions où d’un nouveau paradigme fiscal entre l’État et elles opèrent afin de permettre aux acteurs les entreprises qui vise à assurer la viabilité de économiques de comprendre leur contribution l’État en tant que fournisseur de services sociaux. -

Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Adams. Abigail, 56 Adams, Frank, 196

Index Accounts Committee, 70. 186 Appropriations. Committee on (House) Adams. Abigail, 56 appointment to the, 321 Adams, Frank, 196 chairman also on Rules, 2 I I,2 13 Adams, Henry, 4 I, 174 chairman on Democratic steering Adams, John, 41,47, 248 committee, 277, 359 Chairmen Stevens, Garfield, and Adams, John Quincy, 90, 95, 106, 110- Randall, 170, 185, 190, 210 111 created, 144, 167. 168, 169, 172. 177, Advertisements, fS3, I95 184, 220 Agriculture. See also Sugar. duties on estimates government expenditures, 170 Jeffersonians identified with, 3 1, 86 exclusive assignment to the, 2 16, 32 1 prices, 229. 232, 261, 266, 303 importance of the, 358 tariffs favoring, 232, 261 within the Joint Budget Committee, 274 Agriculture Department, 303 loses some jurisdiction, 2 10 Aid to Families with Dependent Children members on Budget, 353 (AFDC). 344-345 members on Joint Study Committee on Aldrich, Nelson W., 228, 232. 241, 245, Budget Control, 352 247 privileged in reporting bills, 185 Allen, Leo. 3 I3 staff of the. 322-323 Allison, William B., 24 I Appropriations, Committee on (Senate), 274, 352 Altmeyer, Arthur J., 291-292 American Medical Association (AMA), Archer, William, 378, 381 Army, Ci.S. Spe also War Department 310, 343, 345 appropriation bills amended, 136-137, American Newspaper Publishers 137, 139-140 Association, 256 appropriation increases, 127, 253 American Party, 134 Civil War appropriations, 160, 167 American Political Science Association, Continental Army supplies, I7 273 individual appropriation bills for the. American System, 108 102 Ames, Fisher, 35. 45 mobilization of the Union Army, 174 Anderson, H. W., 303 Arthur, Chester A,, 175, 206, 208 Assay omces, 105, 166 Andrew, John, 235 Astor, John Jacob, 120 Andrews, Mary. -

A Historical Examination of the Constitutionality of the Federal Estate Tax

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 27 (2018-2019) Issue 1 Article 5 October 2018 A Historical Examination of the Constitutionality of the Federal Estate Tax Henry Lowenstein Kathryn Kisska-Schulze Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons Repository Citation Henry Lowenstein and Kathryn Kisska-Schulze, A Historical Examination of the Constitutionality of the Federal Estate Tax, 27 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 123 (2018), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol27/iss1/5 Copyright c 2018 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE FEDERAL ESTATE TAX Henry Lowenstein* and Kathryn Kisska-Schulze** INTRODUCTION During the 2016 presidential campaign debate, Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton vowed to raise the Federal Estate Tax to sixty-five percent,1 while Republican candidate Donald Trump pledged to repeal it as part of his overall tax reform proposal.2 Following his election into the executive seat, President Trump signed into law the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) on December 22, 2017, which encompasses the most comprehensive tax law changes in the United States in decades.3 Although the law does not completely repeal the Estate Tax, it temporarily doubles the estate and gift tax exclusion amounts for estates of decedents dying and gifts made after December 31, 2017, and before January 1, 2026.4 Following candidate Trump’s campaign pledge to repeal the Estate Tax,5 and his subsequent signing of the TCJA into law during his first year of presidency,6 an interesting question resonating from these initiatives is whether the Estate Tax is even constitutional. -

Charles Forelle, James Bandler and Mark Maremont of the Wall Street Journal Win Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting

CONTACT: Molly Lanzarotta March 5, 2013 Harvard Kennedy School Communications 617-495-1144 Patricia Callahan, Sam Roe and Michael Hawthorne of the Chicago Tribune Win Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting CAMBRIDGE, MASS – The $25,000 Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting has been awarded to Patricia Callahan, Sam Roe and Michael Hawthorne of the Chicago Tribune by the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy for their investigative report “Playing with Fire." The Shorenstein Center is part of the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. The Chicago Tribune’s investigative series revealed how a deceptive campaign by the chemical and tobacco industries brought toxic flame retardants into people’s homes and bodies, despite the fact that the dangerous chemicals don’t work as promised. As a result of the investigation, the U.S. Senate revived toxic chemical reform legislation and California moved to revamp the rules responsible for the presence of dangerous chemicals in furniture sold nationwide. “The judges this year were especially struck by the initiative shown in recognizing a very important policy issue embedded in something as familiar and unthreatening as a sofa,” said Alex S. Jones, Director of the Shorenstein Center. “It goes to prove the importance of not just looking, but seeing and acting.” Launched in 1991, the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting honors journalism which promotes more effective and ethical conduct of government, the making of public policy, or the practice of politics by disclosing excessive secrecy, impropriety and mismanagement. The five finalists for the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting were: Alan Judd, Heather Vogell, John Perry, M.B.