Bob Cobbing 1950-1978: Performance, Poetry and the Institution Willey, Stephen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2011 Issue 36

Express Summer 2011 Issue 36 Portrait of a Survivor by Thomas Ország-Land John Sinclair by Dave Russell Four Poems from Debjani Chatterjee MBE Per Ardua Ad Astra by Angela Morkos Featured Artist Lorraine Nicholson, Broadsheet and Reviews Our lastest launch: www.survivorspoetry.org ©Lorraine Nicolson promoting poetry, prose, plays, art and music by survivors of mental distress www.survivorspoetry.org Announcing our latest launch Survivors’ Poetry website is viewable now! Our new Survivors’ Poetry {SP} webite boasts many new features for survivor poets to enjoy such as; the new videos featuring regular performers at our London events, mentees, old and new talent; Poem of the Month, have your say feedback comments for every feature; an incorporated bookshop: www.survivorspoetry.org/ bookshop; easy sign up for Poetry Express and much more! We want you to tell us what you think? We hope that you will enjoy our new vibrant place for survivor poets and that you enjoy what you experience. www.survivorspoetry.org has been developed with the kind support of all the staff, board of trustess and volunteers. We are particularly grateful to Judith Graham, SP trustee for managing the project, Dave Russell for his development input and Jonathan C. Jones of www.luminial.net whom built the website using Wordpress, and has worked tirelessly to deliver a unique bespoke project, thank you. Poetry Express Survivors’ Poetry is a unique national charity which promotes the writing of survivors of mental 2 – Dave Russell distress. Please visit www.survivorspoetry. com for more information or write to us. A Survivor may be a person with a current or 3 – Simon Jenner past experience of psychiatric hospitals, ECT, tranquillisers or other medication, a user of counselling services, a survivor of sexual abuse, 4 – Roy Birch child abuse and any other person who has empathy with the experiences of survivors. -

COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON January 13-16, 2011

COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON JANUARY 13-16, 2011 www.collegebookart.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 WELCOME 4 OFFICERS AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS 6 SPONSORS AND DONORS 7 FUTURE OF THE CBAA 8 SPECIAL EVENTS 9 WORKSHOPS 11 TOURS 12 MEETING FINDER, LISTED ALPHABETICALLY 18 MEETING FINDER, LISTED BY DATE AND TIME 22 PROGRAM SCHEDULE 38 CBAA COMMITTEE MEETINGS 39 GENERAL INFORMATION AND MAPS COLLEGE BOOK ART ASSOCIATION MISSION Founded in 2008, The College Book Art Association supports and promotes academic book arts education by fostering the development of its practice, teaching, scholarship and criticism. The College Book Art Association is a non-profit organization fundamentally committed to the teaching of book arts at the college and university level, while supporting such education at all levels, concerned with both the practice and the analysis of the medium. It welcomes as members everyone involved in such teaching and all others who have similar goals and interests. The association aims to engage in a continuing reappraisal of the nature and meaning of the teaching of book arts. The association shall from time to time engage in other charitable activities as determined by the Board of Directors to be appropriate. Membership in the association shall be extended to all persons interested in book arts education or in the furtherance of these arts. For purposes of this constitution, the geographical area covered by the organization shall include, but is not limited to all residents of North America. PRESIDENT’S WELCOME CONFERENCE CHAIR WELCOME John Risseeuw, President 2008-2011 Tony White, Conference Chair Welcome to the College Book Art Association’s 2nd biannual conference. -

Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry

Editorial How to Cite: Parmar, S. 2020. Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry. Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry, 12(1): 33, pp. 1–44. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/bip.3384 Published: 09 October 2020 Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro- duction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-profit publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Sandeep Parmar, ‘Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry.’ (2020) 12(1): 33 Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry. DOI: https://doi. org/10.16995/bip.3384 EDITORIAL Still Not a British Subject: Race and UK Poetry Sandeep Parmar University of Liverpool, UK [email protected] This article aims to create a set of critical and theoretical frameworks for reading race and contemporary UK poetry. By mapping histories of ‘innova- tive’ poetry from the twentieth century onwards against aesthetic and political questions of form, content and subjectivity, I argue that race and the racialised subject in poetry are informed by market forces as well as longstanding assumptions about authenticity and otherness. -

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits?

Performance Poetry New Languages and New Literary Circuits? Cornelia Gräbner erformance poetry in the Western world festival hall. A poem will be performed differently is a complex field—a diverse art form that if, for example, the poet knows the audience or has developed out of many different tradi- is familiar with their context. Finally, the use of Ptions. Even the term performance poetry can easily public spaces for the poetry performance makes a become misleading and, to some extent, creates strong case for poetry being a public affair. confusion. Anther term that is often applied to A third characteristic is the use of vernacu- such poetic practices is spoken-word poetry. At lars, dialects, and accents. Usually speech that is times, they are included in categories that have marked by any of the three situates the poet within a much wider scope: oral poetry, for example, or, a particular community. Oftentimes, these are in the Spanish-speaking world, polipoesía. In the marginalized communities. By using the accent in following pages, I shall stick with the term perfor- the performance, the poet reaffirms and encour- mance poetry and briefly outline some of its major ages the use of this accent and therefore, of the characteristics. group that uses it. One of the most obvious features of perfor- Finally, performance poems use elements that mance poetry is the poet’s presence on the site of appeal to the oral and the aural, and not exclu- the performance. It is controversial because the sively to the visual. This includes music, rhythm, poet, by enunciating his poem before the very recordings or imitations of nonverbal sounds, eyes of his audience, claims authorship and takes smells, and other perceptions of the senses, often- responsibility for it. -

Naked Lunch for Lawyers: William S. Burroughs on Capital Punishment

Batey: Naked LunchNAKED for Lawyers: LUNCH William FOR S. Burroughs LAWYERS: on Capital Punishme WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS ON CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, PORNOGRAPHY, THE DRUG TRADE, AND THE PREDATORY NATURE OF HUMAN INTERACTION t ROBERT BATEY* At eighty-two, William S. Burroughs has become a literary icon, "arguably the most influential American prose writer of the last 40 years,"' "the rebel spirit who has witch-doctored our culture and consciousness the most."2 In addition to literature, Burroughs' influence is discernible in contemporary music, art, filmmaking, and virtually any other endeavor that represents "what Newt Gingrich-a Burroughsian construct if ever there was one-likes to call the counterculture."3 Though Burroughs has produced a steady stream of books since the 1950's (including, most recently, a recollection of his dreams published in 1995 under the title My Education), Naked Lunch remains his masterpiece, a classic of twentieth century American fiction.4 Published in 1959' to t I would like to thank the students in my spring 1993 Law and Literature Seminar, to whom I assigned Naked Lunch, especially those who actually read it after I succumbed to fears of complaints and made the assignment optional. Their comments, as well as the ideas of Brian Bolton, a student in the spring 1994 seminar who chose Naked Lunch as the subject for his seminar paper, were particularly helpful in the gestation of this essay; I also benefited from the paper written on Naked Lunch by spring 1995 seminar student Christopher Dale. Gary Minda of Brooklyn Law School commented on an early draft of the essay, as did several Stetson University colleagues: John Cooper, Peter Lake, Terrill Poliman (now at Illinois), and Manuel Ramos (now at Tulane) of the College of Law, Michael Raymond of the English Department and Greg McCann of the School of Business Administration. -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

Essay by Doug Jones on Bill Griffiths' Poetry

DOUG JONES “I ain’t anyone but you”: On Bill Griffths Bill Griffiths was found dead in bed, aged 59, on September 13, 2007. He had discharged himself from hospital a few days earlier after argu- ing with his doctors. I knew Griffiths from about 1997 to around 2002, a period where I was trying to write a dissertation on his poetry. I spent a lot of time with him then, corresponding and talking to him at length, always keen and pushing to get him to tell me what his poems were about. Of course, he never did. Don’ t think I ever got to know him, really. All this seems a lifetime ago. I’ m now a family physician (a general practitioner in the UK) in a coastal town in England. I’ ve taken a few days off from the COVID calamity and have some time to review the three-volume collection of his work published by Reality Street a few years ago. Volume 1 covers the early years, Volume 2 the 80s, and Volume 3 the period from his move to Seaham, County Durham in northeast England until his death. Here I should attempt do his work some justice, and give an idea, for an American readership, of its worth. Working up to this, I reread much of his poetry, works I hadn’ t properly touched in fifteen years. Going through it again after all that time, I was gobsmacked by its beauty, complexity, and how it continued to burn through a compla- cent and sequestered English poetry scene. -

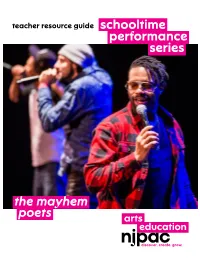

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

Word Is Seeking Poetry, Prose, Poetics, Criticism, Reviews, and Visuals for Upcoming Issues

Word For/ Word is seeking poetry, prose, poetics, criticism, reviews, and visuals for upcoming issues. We read submissions year-round. Issue #30 is scheduled for September 2017. Please direct queries and submissions to: Word For/ Word c/o Jonathan Minton 546 Center Avenue Weston, WV 26452 Submissions should be a reasonable length (i.e., 3 to 6 poems, or prose between 50 and 2000 words) and include a biographical note and publication history (or at least a friendly introduction), plus an SASE with appropriate postage for a reply. A brief statement regarding the process, praxis or parole of the submitted work is encouraged, but not required. Please allow one to three months for a response. We will consider simultaneous submissions, but please let us know if any portion of it is accepted elsewhere. We do not consider previously published work. Email queries and submissions may be sent to: [email protected]. Email submissions should be attached as a single .doc, .rtf, .pdf or .txt file. Visuals should be attached individually as .jpg, .png, .gif, or .bmp files. Please include the word "submission" in the subject line of your email. Word For/ Word acquires exclusive first-time printing rights (online or otherwise) for all published works, which are also archived online and may be featured in special print editions of Word For/Word. All rights revert to the authors after publication in Word For/ Word; however, we ask that we be acknowledged if the work is republished elsewhere. Word For/ Word is open to all types of poetry, prose and visual art, but prefers innovative and post-avant work with an astute awareness of the materials, rhythms, trajectories and emerging forms of the contemporary. -

Experimental Sound & Radio

,!7IA2G2-hdbdaa!:t;K;k;K;k Art weiss, making and criticism have focused experimental mainly on the visual media. This book, which orig- inally appeared as a special issue of TDR/The Drama Review, explores the myriad aesthetic, cultural, and experi- editor mental possibilities of radiophony and sound art. Taking the approach that there is no single entity that constitutes “radio,” but rather a multitude of radios, the essays explore various aspects of its apparatus, practice, forms, and utopias. The approaches include historical, 0-262-73130-4 Jean Wilcox jacket design by political, popular cultural, archeological, semiotic, and feminist. Topics include the formal properties of radiophony, the disembodiment of the radiophonic voice, aesthetic implications of psychopathology, gender differences in broad- experimental sound and radio cast musical voices and in narrative radio, erotic fantasy, and radio as an http://mitpress.mit.edu Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142 Massachusetts Institute of Technology The MIT Press electronic memento mori. The book includes new pieces by Allen S. Weiss and on the origins of sound recording, by Brandon LaBelle on contemporary Japanese noise music, and by Fred Moten on the ideology and aesthetics of jazz. Allen S. Weiss is a member of the Performance Studies and Cinema Studies Faculties at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor experimental edited by allen s. weiss #583606 5/17/01 and edited edited by allen s. weiss Experimental Sound & Radio TDR Books Richard Schechner, series editor Puppets, Masks, and Performing Objects, edited by John Bell Experimental Sound & Radio, edited by Allen S. -

Lee Harwood the INDEPENDENT, 5TH VERSION., Aug 14Odt

' Poet and climber, Lee Harwood is a pivotal figure in what’s still termed the British Poetry Revival. He published widely since 1963, gaining awards and readers here and in America. His name evokes pioneering publishers of the last half-century. His translations of poet Tristan Tzara were published in diverse editions. Harwood enjoyed a wide acquaintance among the poets of California, New York and England. His poetry was hailed by writers as diverse as Peter Ackroyd, Anne Stevenson, Edward Dorn and Paul Auster . Lee Harwood was born months before World War II in Leicester. An only child to parents Wilfred and Grace, he lived in Chertsey. He survived a German air raid, his bedroom window blown in across his bed one night as he slept. His grandmother Pansy helped raise him from the next street while his young maths teacher father served in the war and on to 1947 in Africa. She and Grace's father inspired in Lee a passion for stories. Delicate, gentle, candid and attentive - Lee called his poetry stories. Iain Sinclair described him as 'full-lipped, fine-featured : clear (blue) eyes set on a horizon we can't bring into focus. Harwood's work, from whatever era, is youthful and optimistic: open.' Lee met Jenny Goodgame, in the English class above him at Queen Mary College, London in 1958. They married in 1961. They published single issues of Night Scene, Night Train, Soho and Horde. Lee’s first home was Brick Lane in Aldgate East, then Stepney where their son Blake was born. He wrote 'Cable Street', a prose collage of location and anti fascist testimonial. -

The “Mama of Dada”: Emmy Hennings and the Gender of Poetic Rebellion

The “Mama of Dada”: Emmy Hennings and the Gender of Poetic Rebellion The world lies outside there, life roars there. There men may go where they will. Once we also belonged to them. And now we are forgotten and sunk into oblivion. -“Prison,” Emmy Hennings, 1916 trans. Thomas F. Rugh The Dada “movement” of early twentieth century Europe rejected structure and celebrated the mad chaos of life and art in the midst of World War I. Because Dada was primarily a male-dominated arena, however, the very hierarchies Dadaists professed to reject actually existed within their own art and society—most explicitly in the body of written work that survives today. By focusing on the poetry born from Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, this investigation seeks to explore the variances in style that exist between the male members of Zurich Dada, and the mysterious, oft-neglected matriarch of Cabaret Voltaire, Ms. Emmy Hennings. I posit that these variances may reveal much about how gender influenced the manipulation of language in a counter-culture context such as Dada, and how the performative qualities of Dada poetics further complicated gender roles and power dynamics in the Cabaret Voltaire. Before beginning a critical analysis of the text, it is important to first acknowledge, as Bonnie Kime Scott does in her introduction to The Gender of Modernism, the most basic difference between male and female artists of the early twentieth century: “male participants were quoted, anthologized, taught, and consecrated as geniuses…[while] Women writers were often deemed old-fashioned or of merely anecdotal interest” (2).