The Cat and Mouse Politics of Redistribution: Fair and Effective Representation in British Columbia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile & Investment Guide

Community Profile & Investment Guide September 2019 The Dawson Creek Opportunity Opportunities in industry, adventure, recreation, and education all demonstrate Dawson Creek as “the Capital of the Peace” in Northeastern British Columbia. World-class entertainment and recreation facilities coupled with steadily growing employment markets and low housing costs make Dawson Creek a prime location to grow both your family and business. Add to that the stunning natural beauty enjoyed in the South Peace region’s foothill scenery, and you have an undeniable recipe for a great quality of life. Dawson Creek, the “Capital of the Peace” in Northeastern British Columbia. www.dawsoncreek.ca 2 Welcome to Dawson Creek Welcome to Dawson Creek .............. 3 History .......................................................... 4 Mayor's Message ........................................ 5 Ideal Quality of Life .................................... 6 Abundant Opportunities .......................... 7 Transportation ............................................ 8 he Community Profile and Investment Quick Facts ................................................... 9 TGuide for the City of Dawson Creek Core Infrastructure ...................................10 summarizes the economic well-being of the Investing in Water .....................................11 community and intends to give prospective investors, residents and entrepreneurs an overview of the character and potential of A Diverse, Growing Workforce ...... 12 Dawson Creek and its service area. It is a -

Whether the Honourable Paul Ramsey, Mla, Improperly Influenced The

OPINION OF THE CONFLICT OF INTEREST COMMISSIONER PURSUANT TO SECTION 15(1) OF THE MEMBERS' CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY GORDON CAMPBELL, MEMBER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR VANCOUVER-POINT GREY, AND LEADER OF THE OFFICIAL OPPOSITION WITH RESPECT TO ALLEGED CONTRAVENTION OF PROVISIONS OF THE MEMBERS' CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT BY THE HONOURABLE PAUL RAMSEY, MEMBER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR PRINCE GEORGE NORTH City of Victoria Province of British Columbia May 14, 1998 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY GORDON CAMPBELL, MEMBER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR VANCOUVER-POINT GREY, AND LEADER OF THE OFFICIAL OPPOSITION WITH RESPECT TO ALLEGED CONTRAVENTION OF PROVISIONS OF THE MEMBERS' CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT BY THE HONOURABLE PAUL RAMSEY, MEMBER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR PRINCE GEORGE NORTH Section 19(1) of the Members' Conflict of Interest Act (the Act) provides: A member who has reasonable and probable grounds to believe that another member is in contravention of this Act or of section 25 of the Constitution Act may, by application in writing setting out the grounds for the belief and the nature of the contravention alleged, request that the commissioner give an opinion respecting the compliance of the other member with the provisions of this Act. Pursuant to that section, Gordon Campbell, MLA for Vancouver-Point Grey, wrote to me on the 16th day of March, 1998 requesting an opinion respecting compliance with the provisions of the Act by the Member of the Legislative Assembly for Prince George North, the Honourable Paul Ramsey. That letter contained the following: I submit that there is [sic] reasonable and probable grounds to believe that Mr. -

Order in Council 860/1949

860. Approved and ordered this' b "day of , A.D. 19 4-C\ At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Johnson Mr. Pearson Mr. Wismar Mr. Kenney Mr. Putnam Mr. Carson Mr. Eyres Mr. Straith Mr. Mr. Mr. To His Honour The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to report: THAT it is deemed desirable to appoint further temporary Deputy Registrars of Voters for the various electoral districts of the Province; AND TO /RECOMMEND THAT pursuant to the provisions of sections 7 and 194 of the "Provincial Elections Act", being Chapter 106 of the "Revised Statutes of British Columbia, 1944", the persons whose names appear on the attached list be temporarily appointed Deputy Registrars of Voters for the electoral district shown opposite their respective names at a salary of $173.89 a month plus Cost-of-Living Bonus, and that they be paid for the days that they are actually employed. DOTED this it day of A.D. 1949. 0(7Provincial Secretary. APPROVED this t 7t- day of A.D. 1949. Presiding •Ide21111F—Ortlu tive Council. tiVUA, 1VtALJ, AL.* 4‘.."4)1 0. Ai. 494' rj-SeA, ot-J, 69kt.. .°"/0-/4.e,0 Comichan-Newcastle Electoral District. William Rveleigh General Delivery, Duncan, B.C. Roger Wright Ladysmith, B.C. A.A. Anderson Lake Cosichan Grand Forks—Greenwood Electoral District. Tosh Tanaka Greenwood, B.C. Laslo-Slocan Electoral District. Lloyd Jordan Needles, B.C. John Marshall Burton, B.C. Harry I. Fukushima Slocan City, B.C. Mackenzie Electoral District. Gabriel Bourdon Roberts Creek, B.C. -

Basin Architecture of the North Okanagan Valley Fill, British Columbia

BASIN ARCHITECTURE OF THE NORTH OKANAGAN VALLEY FILL, BRITISH COLUMBIA sandy Vanderburgh B.Sc., University of Calgary I984 M.Sc., University of Calgary 1987 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geography 0 Sandy Vanderburgh SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1993 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL ' Name: Sandy Vanderburgh Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Basin Architecture Of The North Okanagan Valley Fill, British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Alison M. Gill Associate Professor Dr. M.C. Roberts, Protessor Senior Supervisor Idr. H. Hickin, professor Dr. Dirk Tempelman-Kluit, Director Cordilleran Division, Geological Survey of Canada Dr. R.W. Mathewes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences Internal Examiner Dr. James A. Hunter, Senior scientist & Program Co-ordinator, Terrain Sciences Division Geological Survey of Canada External Examiner Date Approved: Julv 16. 1993 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE 8* I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, projector extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

British Columbia School Consolidation from the Perspective of the Prince George Region

CONTEXTUALIZING CONSOLIDATION: BRITISH COLUMBIA SCHOOL CONSOLIDATION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE PRINCE GEORGE REGION by THEODORE D. RENQUIST B. A., Simon Fraser University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Educational Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to tWe^eajlired standard THE^UNIVERSITY OF BR/'TIS H COLUMBIA December, 1994 ©Theodore Renquist, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at The University of British Columbia., I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Educational Studies The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date: August 1994 Abstract Throughout the first half of this century controversy surrounded the division of governance between provincial and local authorities. In a general sense this thesis examines the centralizing forces of equality of opportunity promoted by the provincial government versus the forces of decentralization found in the principle of local autonomy. Specifically this thesis examines the reasons why the school districts in die central interior of British Columbia, around Prince George, were consolidated with little or no opposition in 1946 following the recommendations of the Cameron Report. This thesis is a case study of the region approximately in the center of the province that was to become School District No. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

CONTENTS Trust in Government

QUESTIONS – Tuesday 15 August 2017 CONTENTS Trust in Government ................................................................................................................................ 367 Jobs – Investment in the Northern Territory ............................................................................................ 367 NT News Article ....................................................................................................................................... 368 Same-Sex Marriage Plebiscite ................................................................................................................ 369 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 369 SUPPLEMENTARY QUESTION ................................................................................................................. 370 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 370 Moody’s Credit Outlook ........................................................................................................................... 370 Indigenous Employment .......................................................................................................................... 371 Alcohol-Related Harm Costs ................................................................................................................... 372 Correctional Industries ............................................................................................................................ -

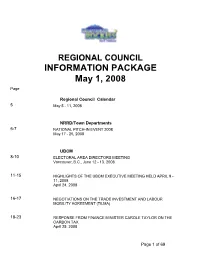

INFORMATION PACKAGE May 1, 2008 Page

REGIONAL COUNCIL INFORMATION PACKAGE May 1, 2008 Page Regional Council Calendar 5 May 5 - 11, 2008 NRRD/Town Departments 6-7 NATIONAL PITCH-IN EVENT 2008 May 17 - 25, 2008 UBCM 8-10 ELECTORAL AREA DIRECTORS MEETING Vancouver, B.C., June 12 - 13, 2008 11-15 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE UBCM EXECUTIVE MEETING HELD APRIL 9 - 11, 2008 April 24, 2008 16-17 NEGOTIATIONS ON THE TRADE INVESTMENT AND LABOUR MOBILITY AGREEMENT (TILMA) 18-23 RESPONSE FROM FINANCE MINISTER CAROLE TAYLOR ON THE CARBON TAX April 25, 2008 Page 1 of 69 Page NCMA 24 NCMA 53RD ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING & CONVENTION Prince George B.C., May 7 - 9, 2008 News Release, April 25, 2008 Provincial Ministries 25-26 CANADA-BRITISH COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL RURAL INFRASTRUCTURE FUND Re: Project #17271 - Water Improvements Project #17328 - Fort Nelson - Downtown Revitalization Improvements Project #17329 - Fort Nelson Sewer Rehabilitation 27-28 MINISTER OF ENERGY, MINES AND PETROLEUM RESOURCES, THE HONOURABLE RICHARD NEUFELD INVITATION TO BRITISH COLUMBIA OIL AND GAS SERVICE SECTOR TRADESHOW Calgary AB, June 2, 2008 29-32 MINISTRY OF FINANCE, CAROLE TAYLOR Response Letter To Mayor Morey Regarding the Proposed Carbon Tax in BC's 2008 Budget 33-36 MINISTRY OF SMALL BUSINESS AND REVENUE AND MINISTER RESPONSIBLE FOR REGULATORY REFORM Implementation and Invitation to Join the BizPaL Partnerships in 2008 Miscellaneous Correspondence 37-45 NORTHERN MEDICAL PROGRAMS TRUST Annual General Meeting, Prince George, B.C., May 8, 2008 Essay: Available as Documents Available Upon Request 46-47 PAT BELL, MLA, PRINCE GEORGE NORTH Top 10, Forestry Round Table and it's Mandate Page 2 of 69 Page Miscellaneous Correspondence 48-53 THE COUNCIL OF CANADIANS Re: TILMA Negotiations News Articles 54 250 NEWS Fort St. -

Theparliamentarian

100th year of publishing TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2019 | Volume 100 | Issue Three | Price £14 The Commonwealth: Adding political value to global affairs in the 21st century PAGES 190-195 PLUS Emerging Security Issues Defending Media Putting Road Safety Building A ‘Future- for Parliamentarians Freedoms in the on the Commonwealth Ready’ Parliamentary and the impact on Commonwealth Agenda Workforce Democracy PAGE 222 PAGES 226-237 PAGE 242 PAGE 244 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance, and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. 64th COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE Calendar of Forthcoming Events KAMPALA, UGANDA Confirmed as of 6 August 2019 22 to 29 SEPTEMBER 2019 (inclusive of arrival and departure dates) 2019 August For further information visit www.cpc2019.org and www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpc2019 30 Aug to 5 Sept 50th CPA Africa Regional Conference, Zanzibar. CONFERENCE THEME: ‘ADAPTION, ENGAGEMENT AND EVOLUTION OF September PARLIAMENTS IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING COMMONWEALTH’. 19 to 20 September Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) British Islands and Mediterranean Regional Conference, Jersey 22 to 29 September 64th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference (CPC), Kampala, Uganda – including 37th CPA Small Branches Conference and 6th Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Conference. October 8 to 10 October 3rd Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Australia Regional Conference, South Australia. November 18 to 21 November 38th CPA Australia and Pacific Regional Conference, South Australia. November 2019 10th Commonwealth Youth Parliament, New Delhi, India - final dates to be confirmed. 2020 January 2020 25th Conference of the Speakers and Presiding Officers of the Commonwealth (CSPOC), Canada - final dates to be confirmed. -

Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau

LATE PREHISTORIC CULTURAL HORIZONS ON THE CANADIAN PLATEAU Department of Archaeology Thomas H. Richards Simon Fraser University Michael K. Rousseau Publication Number 16 1987 Archaeology Press Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Roy L. Carlson (Chairman) Knut R. Fladmark Brian Hayden Philip M. Hobler Jack D. Nance Erie Nelson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 0-86491-077-0 PRINTED IN CANADA The Department of Archaeology publishes papers and monographs which relate to its teaching and research interests. Communications concerning publications should be directed to the Chairman of the Publications Committee. © Copyright 1987 Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Late Prehistoric Cultural Horizons on the Canadian Plateau by Thomas H. Richards and Michael K. Rousseau Department of Archaeology Simon Fraser University Publication Number 16 1987 Burnaby, British Columbia We respectfully dedicate this volume to the memory of CHARLES E. BORDEN (1905-1978) the father of British Columbia archaeology. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................vii List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................iv -

Order in Council 2315/1966

2315. Approved and ordered this 5th day of August , A.D. 19 66. At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, Lieutenant-Governor. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Martin Mr. Black Mr. Bonner Mr. Villiston Mr. Brothers Mr. Gaglardi Mr. Peterron Mr. Loffmark Mr. Campbell Mr. Chant Mr. Kinrnan Mr. Mr. Mr. To His Honour (c77/77 The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend X 4,14 49/to •‘4":7151° 0 A ••>/v ',4 / THAT under the provisions of Section 34 of the "Provincial Elections Act" being Chapter 306 of the Revised Statutes of British Columbia, 1960" each of the persons whose names appear on the list attached hereto be appointed Returning Officer in and for the electoral district set out opposite their respective names; AND THAT the appointments of Returning Officers heretofor made are hereby rescinded. DATED this day of August A.D. 1966 Provincial Secretary APPROVED this day of Presiding Member of the Executive Council Returning Officers - 1966 Electoral District Name Alberni Thomas Johnstone, Port Alberni Atlin Alek S. Bill, Prince Rupert Boundary-Similkameen A. S. Wainwright, Cawston Burnaby-Edmond s W. G. Love, Burnaby Burnaby North E. D. Bolick, Burnaby Burnaby-Willingdon Allan G. LaCroix, Burnaby Cariboo E. G. Woodland, Williams Lake Chilliwack Charles C. Newby, Sardis Columbia River T. J. Purdie, Golden Comox W. J. Pollock, Comox Coquitlam A. R. Ducklow, New Westminster Cowichan-Malahat Cyril Eldred, Cobble Hill Delta Harry Hartley, Ladner Dewdney Mrs. D. J. Sewell, Mission Esquimalt H. F. Williams, Victoria Fort George John H. Robertson, Prince George Kamloops Edwin Hearn, Kamloops Kootenay Mrs. -

Order in Council 1780/1986

COLUMBIA 1780 APPROVED AND ORDERED SEP 24.1986 Lieutenant-Governer EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA SEP 24.1986 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that a general election be held in all the electoral districts for the election of members to serve in the Legislative Assembly; AND FURTHER ORDERS THAT Writs of Election be issued on September 24, 1986 in accordance with Section 40 of the Election Act; AND THAT in each electoral district the place for the nomination of candidates for election to membership and service in the Legislative Assembly shall be the office of the Returning Officer; AND THAT A Proclamation to that end be made. ...-- • iti PROVINCI1‘( ,IT/ ECRETARYT(' AND MINISTER OF GOVERNMENT SERVICES PRESIDING MEMBER OF THE E ECUTIVE COUNCIL (This part is for administrative purposes and it not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Election Act - sec. 33 f )40 Act and section. Other (specify) Statutory authority checked r9Z 4,4fAr 6-A (Signet, typed or printed name of Legal OfOra) ELECTION ACT WRIT OF ELECTION FORM 1 (section 40) ELIZABETH II, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her Other Realms and Territories, QUEEN, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. To the Returning Officer of the Electoral District of Coquitlam-Moody GREETING: We command you that, notice of time and place of election being given, you do cause election to be made, according to law, of a member (or members