Cyber Civil Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miscavige Legal Statements: a Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection

SPEAKING OUT ABOUT ORGANIZED SCIENTOLOGY ~ The Collected Works of L. H. Brennan ~ Volume 1 The Miscavige Legal Statements: A Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection Written by Larry Brennan [Edited & Compiled by Anonymous w/ <3] Originally posted on: Operation Clambake Message board WhyWeProtest.net Activism Forum The Ex-scientologist Forum 2006 - 2009 Page 1 of 76 Table of Contents Preface: The Real Power in Scientology - Miscavige's Lies ...................................................... 3 Introduction to Scientology COB Public Record Analysis....................................................... 12 David Miscavige’s Statement #1 .............................................................................................. 14 David Miscavige’s Statement #2 .............................................................................................. 16 David Miscavige’s Statement #3 .............................................................................................. 20 David Miscavige’s Statement #4 .............................................................................................. 21 David Miscavige’s Statement #5 .............................................................................................. 24 David Miscavige’s Statement #6 .............................................................................................. 27 David Miscavige’s Statement #7 .............................................................................................. 29 David Miscavige’s Statement #8 ............................................................................................. -

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brandоаlionоаsuede Desert Poncho

Free Knitting Pattern Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 Free Knitting Pattern from Lion Brand Yarn Lion Brand® Lion® Suede Desert Poncho Pattern Number: 40607 SKILL LEVEL: Intermediate (Level 3) SIZE: Small, Medium, Large Width 10 (10½, 11)" [25.5 (26.5, 28) cm] at neck; 60 ½ (64, 68½)" [153.5 (162.5, 174) cm] at lower edge Length 23 (25½, 28)" [58.5 (65, 71) cm] at sides; 30 (32 ½, 35)" [76 (82.5, 89) cm] at points Note: Pattern is written for smallest size with changes for larger sizes in parentheses. When only one number is given, it applies to all sizes. To follow pattern more easily, circle all numbers pertaining to your size before beginning. CORRECTIONS: None as of Jun 30, 2016. To check for later updates, click here. MATERIALS • 210126 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Coffee 6 (6, 7) Balls (A) • 210125 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Mocha *Lion® Suede (Article #210). 100% Polyester; package size: Solids: 3.00 3 (4, 4) Balls (B) oz./85g; 122 yd/110m balls • 210098 Lion Brand Lion Suede Yarn: Ecru Prints: 3:00 oz/85g; 111 yd/100m balls 3 (4, 4) Balls (C) • Lion Brand Crochet Hook Size H8 (5 mm) • Lion Brand Split Ring Stitch Markers • Additional Materials • Size 8 [5 mm] 24" [60 cm] circular needles • Size 8 [5 mm] 40" [100 cm] circular needles or size needed to obtain gauge • Size 6 [4 mm] 16" [40 cm] circular needles GAUGE: 14 sts + 23 rnds = 4" [10 cm] in Stockinette st (knit every rnd) on larger needle. -

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (Revised 3/15/19)

John Ball Zoo Exhibit Animals (revised 3/15/19) Every effort will be made to update this list on a seasonal basis. List subject to change without notice due to ongoing Zoo improvements or animal care. North American Wetlands: Muted Swans Mallard Duck Wild Turkey (off Exhibit) Egyptian Goose American White pelican (located in flamingo exhibit during winter months) Bald Eagle Wild Way Trail: (seasonal) Red-necked wallaby Prehensile tail porcupine Ring-tailed lemur Howler Monkey Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Red’s Hobby Farm: Domestic goats Domestic sheep Chickens Pied Crow Common Barn Owl Budgerigar (seasonal) Bali Mynah (seasonal) Crested Wood Partridge (seasonal) Nicobar Pigeon (seasonal) John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Frogs: Smokey Jungle frogs Chacoan Horned frog Tiger-legged monkey frog Vietnamese Mossy frog Mission Golden-eyed Tree frog Golden Poison dart frog American bullfrog Multiple species of poison dart frog North America: Golden Eagle North American River Otter Painted turtle Blanding’s turtle Common Map turtle Eastern Box turtle Red-eared slider Snapping turtle Canada Lynx Brown Bear Mountain Lion/Cougar Snow Leopard South America: South American tapir Crested screamer Maned Wolf Chilean Flamingo Fulvous Whistling Duck Chiloe Wigeon Ringed Teal Toco Toucan (opening in late May) White-faced Saki monkey John Ball Zoo www.jbzoo.org Africa: Chimpanzee Lion African ground hornbill Egyptian Geese Eastern Bongo Warthog Cape Porcupine (off exhibit) Von der Decken’s hornbill (off exhibit) Forest Realm: Amur Tigers Red Panda -

Privacy Online: a Report to Congress

PRIVACY ONLINE: A REPORT TO CONGRESS FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION JUNE 1998 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Robert Pitofsky Chairman Mary L. Azcuenaga Commissioner Sheila F. Anthony Commissioner Mozelle W. Thompson Commissioner Orson Swindle Commissioner BUREAU OF CONSUMER PROTECTION Authors Martha K. Landesberg Division of Credit Practices Toby Milgrom Levin Division of Advertising Practices Caroline G. Curtin Division of Advertising Practices Ori Lev Division of Credit Practices Survey Advisors Manoj Hastak Division of Advertising Practices Louis Silversin Bureau of Economics Don M. Blumenthal Litigation and Customer Support Center Information and Technology Management Office George A. Pascoe Litigation and Customer Support Center Information and Technology Management Office TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................... i I. Introduction ........................................................... 1 II. History and Overview .................................................... 2 A. The Federal Trade Commission’s Approach to Online Privacy ................. 2 B. Consumer Privacy Online ............................................. 2 1. Growth of the Online Market ...................................... 2 2. Privacy Concerns ............................................... 3 C. Children’s Privacy Online ............................................. 4 1. Growth in the Number of Children Online ............................ 4 2. Safety and Privacy Concerns ...................................... 4 III. Fair -

Jan. 21St Babbage’S Son IBM Antitrust Calculates Jan

mirror with a $10 cylindrical In his spare time, Starkweather lens. was an avid model railroader. Jan. 21st Babbage’s Son IBM Antitrust Calculates Jan. 21, 1952 The US Department of Justice’s Jan. 21, 1888 (DOJ) filed an antitrust suit Charles Babbage [Dec 26] never against IBM [Feb 14], charging it constructed an Analytical Engine with unlawful restraint of trade, [Dec 23], but his youngest son, and domination of the punch Henry Prevost Babbage (1824- card industry. At the time, IBM 1918), did get around to owned more than 90% of all the building the mill portion (the tabulating machines in the US, arithmetic logic unit) from his and manufactured and sold father’s plans. about 90% of all the cards. On this day, it produced a table Gary Starkweather (2009). A consent decree was issued in of multiples of , complete to 29 Photo by Dcoetzee. CC0. 1956, instructing the company digits, arguably making it the to reduce its share of the market first successful test of a Incredibly, his work generated to a more reasonable 50%. This computer. Over twenty years almost no interest at Webster, was fortuitous timing for Tom later, in April 1910, the results and his manager actually Watson, Jr. [Jan 14] who had just were published in The Monthly threatened to sack anyone who taken over as IBM's CEO; he Notices of the Royal Astronomical 'wasted their time' on the wanted to move the company's Society, followed by errata in the project. focus away from punched card June issue. systems towards computers. -

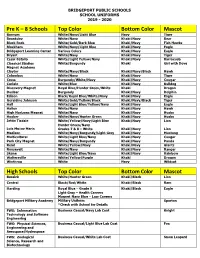

8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot

BRIDGEPORT PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL UNIFORMS 2019 - 2020 Pre K – 8 Schools Top Color Bottom Color Mascot Barnum White/Navy/Light Blue Navy Tiger Beardsley White/Navy Khaki/Navy Bear Black Rock White/Gold/Dark Blue Khaki/Navy Fish Hawks Blackham White/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Eagle Bridgeport Learning Center Various Colors Khaki/Navy Eagle Bryant White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger César Batalla White/Light Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Barracuda Classical Studies White/Burgundy Khaki Girl with Dove Magnet Academy Claytor White/Navy/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Hawk Columbus White/Navy Khaki/Navy Tiger Cross Burgundy/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Curiale White/Blue Khaki/Navy Bulldog Discovery Magnet Royal Blue/Hunter Green/White Khaki Dragon Dunbar Burgundy Khaki/Navy Dolphin Edison Black/Royal Blue/White/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Geraldine Johnson White/Gold/Yellow/Black Khaki/Navy/Black Tiger Hall White/Light Blue/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Eagle Hallen White/Navy Khaki/Navy Hawk High Horizons Magnet White/Navy Khaki/Navy Husky Hooker White/Navy/Hunter Green Khaki/Navy Husky Jettie Tisdale White/Yellow/Navy/Light Blue Khaki/Navy Lion Hunter Green/Navy Luis Muñoz Marín Grades 7 & 8 – White Khaki/Navy Lion Madison White/Navy/Burgundy/Light Grey Khaki/Navy Mustang Multicultural White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Cougar Park City Magnet White/Navy/Burgundy Khaki/Navy Panda Read White/Yellow/Navy Khaki/Navy Giants Roosevelt White/Navy Khaki/Navy Ranger Skane White/Light Blue/Navy Khaki/Navy Rainbow Waltersville White/Yellow/Purple Khaki Dragon Winthrop White Navy Wildcat -

Colours in Nature Colours

Nature's Wonderful Colours Magdalena KonečnáMagdalena Sedláčková • Jana • Štěpánka Sekaninová Nature is teeming with incredible colours. But have you ever wondered how the colours green, yellow, pink or blue might taste or smell? What could they sound like? Or what would they feel like if you touched them? Nature’s colours are so wonderful ColoursIN NATURE and diverse they inspired people to use the names of plants, animals and minerals when labelling all the nuances. Join us on Magdalena Konečná • Jana Sedláčková • Štěpánka Sekaninová a journey to discover the twelve most well-known colours and their shades. You will learn that the colours and elements you find in nature are often closely connected. Will you be able to find all the links in each chapter? Last but not least, if you are an aspiring artist, take our course at the end of the book and you’ll be able to paint as exquisitely as nature itself does! COLOURS IN NATURE COLOURS albatrosmedia.eu b4u publishing Prelude Who painted the trees green? Well, Nature can do this and other magic. Nature abounds in colours of all shades. Long, long ago people began to name colours for plants, animals and minerals they saw them in, so as better to tell them apart. But as time passed, ever more plants, animals and minerals were discovered that reminded us of colours already named. So we started to use the names for shades we already knew to name these new natural elements. What are these names? Join us as we look at beautiful colour shades one by one – from snow white, through canary yellow, ruby red, forget-me-not blue and moss green to the blackest black, dark as the night sky. -

Principles of Internet Privacy

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2000 Principles of Internet Privacy Fred H. Cate Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Computer Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Cate, Fred H., "Principles of Internet Privacy" (2000). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 243. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/243 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Internet Privacy FRED H. CATE* I. INTRODUCTION Paul Schwartz's InternetPrivacy and the State makes an important and original contribution to the privacy debate that is currently raging by be- ginning the process of framing a new and more useful understanding of what "privacy" is and why and how it should be protected.' The definition developed by Brandeis, Warren,2 and Prosser,3 and effectively codified by Alan Westin in 1967---"the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others"---worked well in a world in which most privacy concerns involved physical intrusions (usually by the government) or public disclosures (usually by the media), which, by their very nature, were comparatively rare and usually discovered. -

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age

The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age April 9, 2018 Dr. Keith Goldstein, Dr. Ohad Shem Tov, and Mr. Dan Prazeres Presented on behalf of Pirate Parties International Headquarters, a UN ECOSOC Consultative Member, for the Report of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Our Dystopian Present Living in modern society, we are profiled. We accept the necessity to hand over intimate details about ourselves to proper authorities and presume they will keep this information secure- only to be used under the most egregious cases with legal justifications. Parents provide governments with information about their children to obtain necessary services, such as health care. We reciprocate the forfeiture of our intimate details by accepting the fine print on every form we sign- or button we press. In doing so, we enable second-hand trading of our personal information, exponentially increasing the likelihood that our data will be utilized for illegitimate purposes. Often without our awareness or consent, detection devices track our movements, our preferences, and any information they are capable of mining from our digital existence. This data is used to manipulate us, rob from us, and engage in prejudice against us- at times legally. We are stalked by algorithms that profile all of us. This is not a dystopian outlook on the future or paranoia. This is present day reality, whereby we live in a data-driven society with ubiquitous corruption that enables a small number of individuals to transgress a destitute mass of phone and internet media users. In this paper we present a few examples from around the world of both violations of privacy and accomplishments to protect privacy in online environments. -

The Safeguards of Privacy Federalism

THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM BILYANA PETKOVA∗ ABSTRACT The conventional wisdom is that neither federal oversight nor fragmentation can save data privacy any more. I argue that in fact federalism promotes privacy protections in the long run. Three arguments support my claim. First, in the data privacy domain, frontrunner states in federated systems promote races to the top but not to the bottom. Second, decentralization provides regulatory backstops that the federal lawmaker can capitalize on. Finally, some of the higher standards adopted in some of the states can, and in certain cases already do, convince major interstate industry players to embed data privacy regulation in their business models. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: US PRIVACY LAW STILL AT A CROSSROADS ..................................................... 2 II. WHAT PRIVACY CAN LEARN FROM FEDERALISM AND FEDERALISM FROM PRIVACY .......... 8 III. THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM IN THE US AND THE EU ............................... 18 1. The Role of State Legislatures in Consumer Privacy in the US ....................... 18 2. The Role of State Attorneys General for Consumer Privacy in the US ......... 28 3. Law Enforcement and the Role of State Courts in the US .................................. 33 4. The Role of National Legislatures and Data Protection Authorities in the EU…….. .............................................................................................................................................. 45 5. The Role of the National Highest Courts -

Internet Privacy and the State

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Internet Privacy and the State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37x3z12g Author Schwartz, Paul M Publication Date 2021-06-27 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Berkeley Law Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1999 Internet Privacy and the State Paul M. Schwartz Berkeley Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul M. Schwartz, Internet Privacy and the State, 32 Conn. L. Rev. 815 (1999), Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs/766 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interet Privacy and the State PAUL M. SCHWARTZ" INTRODUCTION "Of course you are right about Privacy and Public Opinion. All law is a dead letter without public opinion behind it. But law and public opinion in-1 teract-and they are both capable of being made." Millions of people now engage in daily activities on the Internet, and under current technical configurations, this behavior generates finely grained personal data. In the absence of effective limits, legal or other- wise, on the collection and use of personal information on the Internet, a new structure of power over individuals is emerging. This state of affairs has significant implications for democracy in the United States, and, not surprisingly, has stimulated renewed interest in information privacy? Yet, the ensuing debate about Internet privacy has employed a deeply flawed rhetoric. -

A Model Regime of Privacy Protection

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2006 A Model Regime of Privacy Protection Daniel J. Solove George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Solove & Chris Jay Hoofnagle, A Model Regime of Privacy Protection, 2006 U. Ill. L. Rev. 357 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLOVE.DOC 2/2/2006 4:27:56 PM A MODEL REGIME OF PRIVACY PROTECTION Daniel J. Solove* Chris Jay Hoofnagle** A series of major security breaches at companies with sensitive personal information has sparked significant attention to the prob- lems with privacy protection in the United States. Currently, the pri- vacy protections in the United States are riddled with gaps and weak spots. Although most industrialized nations have comprehensive data protection laws, the United States has maintained a sectoral approach where certain industries are covered and others are not. In particular, emerging companies known as “commercial data brokers” have fre- quently slipped through the cracks of U.S. privacy law. In this article, the authors propose a Model Privacy Regime to address the problems in the privacy protection in the United States, with a particular focus on commercial data brokers. Since the United States is unlikely to shift radically from its sectoral approach to a comprehensive data protection regime, the Model Regime aims to patch up the holes in ex- isting privacy regulation and improve and extend it.