Imagining Henry Viii: Cultural Memory and the Tudor King, 1535-1625

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A HISTORY OF LAUREATE POETICS, 1399-1616 Christine Maffuccio, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Theresa Coletti Department of English My dissertation analyzes lowbrow literary forms, tropes, and modes in the writings of three would-be laureates, writers who otherwise sought to align themselves with cultural and political authorities and who themselves aspired to national prominence: Thomas Hoccleve (c. 1367-1426), John Skelton (c. 1460-1529), and Ben Jonson (1572-1637). In so doing, my project proposes a new approach to early English laureateship. Previous studies assume that aspiration English writers fashioned their new mantles exclusively from high learning, refined verse, and the moral virtues of elite poetry. In the writings and self-fashionings that I analyze, however, these would-be laureates employed literary low culture to insert themselves into a prestigious, international lineage; they did so even while creating personas that were uniquely English. Previous studies have also neglected the development of early laureateship and nationalist poetics across the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. Examining the ways that cultural cachet—once the sole property of the elite—became accessible to popular audiences, my project accounts for and depends on a long view. My first two chapters analyze writers whose idiosyncrasies have afforded them a marginal position in literary histories. In Chapter 1, I argue that Hoccleve channels Chaucer’s Host, Harry Bailly, in the Male Regle and the Series. Like Harry, Hoccleve draws upon quotidian London experiences to create a uniquely English writerly voice worthy of laureate status. In Chapter 2, I argue that Skelton enshrine the poet’s own fleeting historical experience in the Garlande of Laurell and Phyllyp Sparowe by employing contrasting prosodies to juxtapose the rhythms of tradition with his own demotic meter. -

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590S Alan

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590s Alan C. Dessen [Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England’s First Notorious Professional Writer, ed. Kirk Melnikoff and Edward Gieskes (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 25-37.\ Here is a familiar tale found in literary handbooks for much of the twentieth century. Once upon a time in the 1560s and 1570s (the boyhoods of Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson) English drama was in a deplorable state characterized by fourteener couplets, allegory, the heavy hand of didacticism, and touring troupes of players with limited numbers and resources. A first breakthrough came with the building of the first permanent playhouses in the London area in 1576- 77 (The Theatre, The Curtain)--hence an opportunity for stable groups to form so as to develop a repertory of plays and an audience. A decade later the University Wits came down to bring their learning and sophistication to the London desert, so that the heavyhandedness and primitive skills of early 1580s playwrights such as Robert Wilson and predecessors such as Thomas Lupton, George Wapull, and William Wager were superseded by the artistry of Marlowe, Kyd, and Greene. The introduction of blank verse and the suppression of allegory and onstage sermons yielded what Willard Thorp billed in 1928 as "the triumph of realism."1 Theatre and drama historians have picked away at some of these details (in particular, 1576 has lost some of its luster or uniqueness), but the narrative of the University Wits' resuscitation of a moribund English drama has retained its status as received truth. -

The Six Wives of King Henry Viii

THE SIX WIVES OF KING HENRY VIII Divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived! Ready for a trip back in time? Here at Nat Geo Kids, we’re travelling back to Tudor England in our Henry VIII wives feature. Hold onto your hats – and your heads! Henry VIII wives… 1. Catherine of Aragon Henry VIII’s first wife was Catherine of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Eight years before her marriage to Henry in 1509, Catherine was in fact married to Henry’s older brother, Arthur, who died of sickness at just 15 years old. Together, Henry and Catherine had a daughter, Mary – but it was a son that Henry wanted. Frustrated that Catherine seemed unable to produce a male heir to the throne, Henry had their marriage annulled (cancelled) in 1533. But there’s more to the story – towards the end of their marriage, Henry fell in love with one of Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting (woman who assisted the queen) – Anne Boleyn… 2. Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn became Henry’s second wife after the pair married secretly in January 1533. By this time, Anne was pregnant with her first child to Henry, and by June 1533 she was crowned Queen of England. Together they had a daughter, Elizabeth – the future Queen Elizabeth I. But, still, it was a son – and future king of England – that Henry wanted. Frustrated, he believed his marriage was cursed and that Anne was to blame. And so, he turned his affections to one of Anne’s ladies-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. -

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, C

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, c. 1515‐1541 by Chad T. Marshall BA (Hons., Archaeology, Toronto), MA (History and Classics, Tasmania) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, December, 2018 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 i Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 ii Acknowledgements This thesis is for my wife, Elizabeth van der Geest, a woman of boundless beauty, talent, and mystery, who continuously demonstrates an inestimable ability to elevate the spirit, of which an equal part is given over to mastery of that other vital craft which serves to refine its expression. I extend particular gratitude to my supervisors: Drs. Gavin Daly and Michael Bennett. They permitted me the scope to explore the arena of Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland and England, and skilfully trained wide‐ranging interests onto a workable topic and – testifying to their miraculous abilities – a completed thesis. Thanks, too, to Peter Crooks of Trinity College Dublin and David Heffernan of Queen’s University Belfast for early advice. -

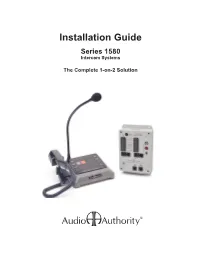

1580 Series Manual

Installation Guide Series 1580 Intercom Systems The Complete 1-on-2 Solution 2048 Mercer Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40511-1071 USA Phone: 859-233-4599 • Fax: 859-233-4510 Customer Toll-Free USA & Canada: 800-322-8346 www.audioauthority.com • [email protected] 2 Contents Introducing Series 1580 Intercom Systems 4 Series 1580 System Components 4 1580S and 1580HS Kits 4 Audio Installation 5 Lane Cable Information 6 Wiring 6 Advertising Messages 7 Traffic Sensors 8 Basic Calibration and Testing 9 Self Setup Mode 9 Troubleshooting Tips 9 Operation 10 Operator Guide 11 Using the 1550A Setup Tool 12 Advanced Calibration and Setup 12 Power User Tips 12 1550A Configuration Example 13 Definitions 14 Appendix 15 WARNINGS • Read these instructions before installing or using this product. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose components to rain or moisture • This product must be installed by qualified personnel. • Do not expose this unit to excessive heat. • Clean the unit only with a dry or slightly dampened soft cloth. LIABILITY STATEMENT Every effort has been made to ensure that this product is free of defects. Audio Authority® cannot be held liable for the use of this hardware or any direct or indirect consequential damages arising from its use. It is the responsibility of the user of the hardware to check that it is suitable for his/her requirements and that it is installed correctly. All rights are reserved. No parts of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written consent of the publisher. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Written Guide

The tale of a tail A self-guided walk along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail from the Scottish Parliament Building © Rory Walsh RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The tale of a tail Discover the stories along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile A 1647 map of The Royal Mile. Edinburgh Castle is on the left Courtesy of www.royal-mile.com Lined with cobbles and layered with history, Edinburgh’s ‘Royal Mile’ is one of Britain’s best-known streets. This famous stretch of Scotland’s capital also attracts visitors from around the world. This walk follows the Mile from historic Edinburgh Castle to the modern Scottish Parliament. The varied sights along the way reveal Edinburgh’s development from a dormant volcano into a modern city. Also uncover tales of kidnap and murder, a dramatic love story, and the dramatic deeds of kings, knights and spies. The walk was originally created in 2012. It was part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

Anna of Cleves Birth and Death 1515 – July 16, 1557

Catherine of Aragon Birth and death December 15, 1485 – January 7, 1536 Marriage One: to Arthur (Henry’s older brother), November 14, 1501 (aged 15) Two: to Henry VIII, June 11, 1509 (aged 23) Children Mary, born February 18, 1516 (later Queen Mary I). Catherine also had two other children who died as infants, three stillborn children, and several miscarriages. Interests Religion, sewing, dancing, a bit more religion. Cause of death Probably a type of cancer. Remembered for… Her refusal to accept that her marriage was invalid; her faith; her dramatic speech to Henry when he had her brought to court to seek the annulment of their marriage. Did you know? While Henry fought in France in 1513, Catherine was regent during the Battle of Flodden; when James IV of Scotland was killed in the battle, Catherine wanted to send his body to Henry as a present. Anne Boleyn Birth and death c. 1501 – May 19, 1536 Marriage January 25, 1533 (aged 31) Children Elizabeth, born September 7, 1533 (later Queen Elizabeth I). Anne also had at least two miscarriages. Interests Fashion, dancing, flirtation, collecting evangelical works. Queen Links Lady-in-waiting to Catherine of Aragon. Cause of death Executed on Tower Green, London. Remembered for… Headlessness; bringing about England’s break with the Pope; having a sixth fingernail. Did you know? Because she was fluent in French, Anne would have acted as a translator during the visit of Emperor Charles V to court in 1522. Jane Seymour Birth and death 1507 or 1508 – October 24, 1537 Marriage May 30, 1536 (aged 28 or 29) Children Edward, born October 12, 1537 (later King Edward VI). -

Reformation Roots Edited by John B

THE LIVING THEOLOGICAL HERITAGE OF THE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST Barbara Brown Zikmund Series Editor L T H VOLUME TWO Reformation Roots Edited by John B. Payne The Pilgrim Press Cleveland, Ohio Contents The Living Theological Heritage of the United Church of Christ ix Reformation Roots 1 Part L Late Medieval and Renaissance Piety and Theology 37 1. The Book of the Craft of Dying (c. mid-15th century) 37 2. The Imitation of Christ (c. 1427) 51 THOMAS À KEMPIS 3. Eternal Predestination and Its Execution in Time (1517) 69 JOHN VON STAUPITZ 4.Paraclesis(1516) 86 DESIDERIUS ERASMUS Part II. Reformation in Germany, Switzerland, and the 98 Netherlands Martin Luther and the German Reformation 5. The Freedom of a Christian (1520) 98 MARTIN LUTHER 6. Formula of Mass and Communion for the Church 121 at Wittenberg (1523) MARTIN LUTHER 7. Hymn: Out of the Depths I Cry to Thee (1523) 137 MARTIN LUTHER 8. Small Catechism (1529) 140 MARTIN LUTHER 9. The Augsburg Confession (1530) 160 Zwingli and the Swiss Reformation 10. Sixty-Seven Articles (1523) 196 ULRICH ZWINGLI 11. Action or Use of the Lord's Supper (1525) 205 ULRICH ZWINGLI 12. The Schleitheim Confession of Faith (1527) 214 13. The Marburg Colloquy (1529) 224 VI • CONTENTS 14. Sermon One, Decade One: Of the Word of God 248 from Decades (1549-51) HEINRICH BULLINGER Calvin and the Genevan Reformation 15. The Law from Institution of the Christian Religion (1536) 266 JOHN CALVIN 16. The Geneva Confession (1536) 272 WILLIAM FAREL AND JOHN CALVIN 17. The Strasbourg Liturgy (1539) 280 MARTIN BUCER 18. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture.