Fishel Fog of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Annual Report

The New Conservative Flagship ANNUAL REPORT 2020A About American Compass Table of Contents Our Mission To restore an economic consensus that emphasizes the importance of family, community, and industry to the nation’s liberty and prosperity: 1 Founder’s Letter 4 REORIENTING POLITICAL FOCUS from growth for its own sake to widely shared economic development that sustains vital social institutions. SETTING A COURSE for a country in which families can achieve self- sufficiency, contribute productively to their communities, and prepare the next 2 Year in Review 10 generation for the same. Conservative Flagship 12 HELPING POLICYMAKERS NAVIGATE the limitations that markets and government each face in promoting the general welfare and the nation’s security. Changing the Debate 14 Our Activities Creating Community 16 AFFILIATION. Providing opportunities for people who share its mission to The Commons 18 build relationships, collaborate, and communicate their views to the broader political community. Our Growing Influence 20 DELIBERATION. Supporting research and discussion that advances understanding of economic and social conditions and tradeoffs through study of history, analysis of data, elaboration of theory, and development of policy 3 Our Work 21 proposals. ENGAGEMENT. Initiating and facilitating public debate to challenge existing Rebooting the American System 22 orthodoxy, confront the best arguments of its defenders, and force scrutiny of unexamined assumptions and unconsidered consequences. Coin-Flip Capitalism 26 Our Principles Moving the Chains 30 AMERICAN COMPASS strives to embody the principles and practices of a healthy democratic polity, combining intellectual combat with personal civility. Corporate Actual Responsibility 34 We welcome converts to our vision and value disagreement amongst A Seat at the Table 38 our members. -

PDF Van Tekst

Onze Taal. Jaargang 73 bron Onze Taal. Jaargang 73. Genootschap Onze Taal, Den Haag 2004 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_taa014200401_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. 1 [Nummer 1] Onze Taal. Jaargang 73 4 Vervlakt de intonatie? Ouderen en jongeren met elkaar vergeleken Vincent J. van Heuven - Fonetisch Laboratorium, Universiteit Leiden Ouderen kunnen jongeren vaak maar moeilijk verstaan. Ze praten te snel, te slordig en vooral te monotoon, zo luidt de klacht. Zou dat wijzen op een verandering? Wordt de Nederlandse zinsmelodie inderdaad steeds vlakker? Twee onderzoeken bieden meer duidelijkheid. Ik heb twee zoons in de adolescente leeftijdsgroep, zo tussen de 16 en de 20. Toen ik ze nog dagelijks om me heen had (ze zijn inmiddels technisch gesproken volwassen en het huis uit), mocht ik graag luistervinken als ze in gesprek waren met hun vrienden. Dan viel op dat alle jongens, niet alleen de mijne, snel spraken, met weinig stemverheffing, en vooral met weinig melodie. Het leek wel of ze het erom deden. Een Amerikaanse collega, die elk jaar een paar weken bij mij logeert om zijn Nederlands bij te houden, gaf ongevraagd toe dat hij in het algemeen weinig moeite heeft om Nederlanders te verstaan, behalve dan mijn zoons en hun vrienden. Een paar jaar eerder was ik in een onderzoek beoordelaar van de uitspraak van 120 Nederlanders, in leeftijd variërend van puber tot bejaarde. Mij viel op dat de bejaarden zo veel prettiger waren om naar te luisteren. Niet alleen spraken ze langzamer dan de jongeren, maar vooral maakten ze veel beter gebruik van de mogelijkheden die onze taal biedt om de boodschap met behulp van het stemgebruik te structureren. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

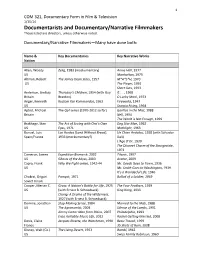

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Michael Moore: a Man on a Mission Or How Far A

Michael Moore: A Man on a Mission or How Far a Reinvigorated Populism Can Take Us Garry Watson (Cineaction 70) My focus in this essay will be on Michael Mooreʼs four documentaries – Roger and Me (1989), The Big One (1997), Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) – with most of my attention being given to the first and third of these, and least to the second. These four films are significant and worth studying for a number of reasons: (i) The size of the audiences they have succeeded in reaching; (ii) the political impact they have had (on which, among other things, see Robert Brent Toplinʼs useful book on Michael Mooreʼs “Fahreneit 9/11”: How One Film Divided A Nation [2006]); (iii) and the extent to which they helped prepare the reception for such recent political documentaries as, for example, Errol Morrisʼs The Fog of War (2004), Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbottʼs The Corporation (2005), Alex Gibneyʼs Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), Eugene Jareckiʼs Why We Fight (2005), David Guggenheimʼs An Inconvenient Truth (2006), and Chris Paineʼs Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006). It may not be redundant to rehearse some of the facts. If Roger and Me was more successful at the box office than any documentary that preceded it, Moore went on to break the same record on two subsequent occasions – first with Bowling for Columbine, then with Fahrenheit 9/11. And as far as the latter is concerned, we get some sense of the excitement that was generated when it first screened in the US by the Foreword that John Berger wrote in 2004 for The Official “Fahrenheit 9/11” Reader (while the film was “still playing in hundreds of theaters across America”1). -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

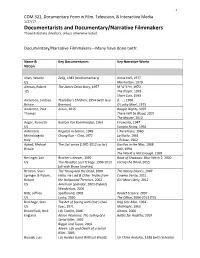

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Empathize with Your Enemy”

PEACE AND CONFLICT: JOURNAL OF PEACE PSYCHOLOGY, 10(4), 349–368 Copyright © 2004, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Lesson Number One: “Empathize With Your Enemy” James G. Blight and janet M. Lang Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies Brown University The authors analyze the role of Ralph K. White’s concept of “empathy” in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vietnam War, and firebombing in World War II. They fo- cus on the empathy—in hindsight—of former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, as revealed in the various proceedings of the Critical Oral History Pro- ject, as well as Wilson’s Ghost and Errol Morris’s The Fog of War. Empathy is the great corrective for all forms of war-promoting misperception … . It [means] simply understanding the thoughts and feelings of others … jumping in imagination into another person’s skin, imagining how you might feel about what you saw. Ralph K. White, in Fearful Warriors (White, 1984, p. 160–161) That’s what I call empathy. We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions. Robert S. McNamara, in The Fog of War (Morris, 2003a) This is the story of the influence of the work of Ralph K. White, psychologist and former government official, on the beliefs of Robert S. McNamara, former secretary of defense. White has written passionately and persuasively about the importance of deploying empathy in the development and conduct of foreign policy. McNamara has, as a policymaker, experienced the success of political decisions made with the benefit of empathy and borne the responsibility for fail- Requests for reprints should be sent to James G. -

The Rules of Engagement in the Conduct of Special Operations

NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California thesis THE RULES OF ENGAGEMENT IN THE CONDUCT OF SPECIAL OPERATIONS by Michael S. Reilly December 1996 Thesis Advisor: John Arquilla Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. SCHOOL Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) | 5! REP6RT t)ATE T. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 1996 Master's Thesis 4. TITLE AMD SUBTITLE T. FUNDING NUMBERS THE RULES OF ENGAGEMENT IN THE CONDUCT OF SPECIAL OPERATIONS 6. AUtHOR(S) Reilly, Michael S. 7. PERFORMING oRgaN1ZaTI6N NaME(S) aND addREss(Es) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey CA 93943-5000 9~ SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10.SPONSOR1NG /MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER 1 1 . SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. 12a. dIstRIbUtIoN/aVaILabILIty STATEMENT T2b! DISTRIBUTION CODE Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. -

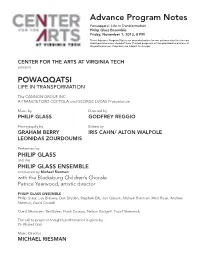

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

ABQ Free Press, August 13, 2014

VOL I, Issue 9, August 13, 2014 Pot Vote: Political Theater? PAGE 5 Joe Monahan: Our Summer of Pain Inside ABQ PAGE 7 TV News PAGE 6 Best Motorcycle Roads in N.M. What You Should PAGE 9 Know about Ebola PAGE 11 Exclusive: Longmire’s Bailey Chase PAGE 14 PAGE 2 • August 13, 2014 • ABQ FREE PRESS NEWS ABQ Free Press Pulp News coMPIlEd By ABQ frEE PrEss sTAff VOL I, Issue 9, August 13, 2014 www.freeabq.com Self-inflicted Musician evicted www.abqarts.com A man berating another motorist after A 97-year-old man was kicked out Editor: rear-ending her car was run over by of his nursing home for refusing to [email protected] his own pickup truck, the Gainesville obey an order from managers to stop Associate Editor, Arts: [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE Sun reported. Joseph Carl, 48, was playing his ukulele. “Management charged with drunken driving after continually suppressed my talents,” Advertising: [email protected] the incident, which left him with a Jim Farrell said. “Management would [email protected] fractured hand and foot. Police said stop me and say these words: ‘Go he registered a blood alcohol level back to your room!’” After being On Twitter: @freeabq of .22 percent, nearly three times the evicted he ended up in a homeless NEWS threshold for drunken driving. shelter. After his plight appeared ABQ Free Press Pulp News ............................................................................................................Page 2 in a local newspaper, Napa Valley Editor Just ducky residents pitched in to help him move Dan Vukelich Our favorite segment ever on Rachel Maddow’s network .............................................................. -

A RESOLUTION to Honor Four-Star General Carl Wade Stiner, Co-Author of Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces, a Best-Selling Book

Filed for intro on 05/01/2002 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 925 By Goins A RESOLUTION to honor Four-Star General Carl Wade Stiner, co-author of Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces, a best-selling book. WHEREAS, this General Assembly is proud to honor those persons whose professional achievements have redounded to the benefit of the public good; and WHEREAS, General Carl Stiner is one such person, whose brilliant and distinguished military career has led to a prominent role in contributing to Shadow Warriors, co-authored by Tom Clancy about the U.S. Special Forces; and WHEREAS, born in LaFollette, General Stiner was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U. S. Army in May, 1958, following graduation from the Tennessee Polytechnical Institute with a Bachelor of Science degree in Agriculture. He later earned a Master of Science degree in Public Administration from Shippensburg State College; and WHEREAS, General Stiner was the Second Commander-in-Chief of the United States Special Operations Command headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, from May, 1990 to May, 1993. As Commander-in-Chief, he was responsible for the readiness of all Special Operations Forces of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, both in active duty and the reserves; and HJR0925 01425247 -1- WHEREAS, his major assignments include duty as Company Commander of the 5th Battalion, 1st Training Brigade. From August, 1964 until May, 1966, he was assigned to the 3rd Special Forces Group as Detachment Command and Company Operations Officer; and WHEREAS, following a tour in Southeast Asia, General Stiner reported for assignment to the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, U. -

Programming Notes - First Read

Programming notes - First Read Hotmail More TODAY Nightly News Rock Center Meet the Press Dateline msnbc Breaking News EveryBlock Newsvine Account ▾ Home US World Politics Business Sports Entertainment Health Tech & science Travel Local Weather Advertise | AdChoices Recommended: Recommended: Recommended: 3 Recommended: First Thoughts: My, VIDEO: The Week remaining First Thoughts: How New iPads are Selling my, Myanmar That Was: Gifts, undecided House Rebuilding time for Under $40 fiscal cliff, and races verbal fisticuffs How Cruise Lines Fill All Those Unsold Cruise Cabins What Happens When You Take a Testosterone The first place for news and analysis from the NBC News Political Unit. Follow us on Supplement Twitter. ↓ About this blog ↓ Archives E-mail updates Follow on Twitter Subscribe to RSS Like 34k 1 comment Recommend 3 0 older3 Programming notes newer days ago *** Friday's "The Daily Rundown" line-up with guest host Luke Russert: NBC's Kelly O'Donnell on Petraeus' testimony… NBC's Ayman Mohyeldin live in Gaza… one of us (!!!) with more on the Republican reaction to Romney… NBC's Mike Viqueira on today's White House meeting on the fiscal cliff and The Economist's Greg Ip and National Journal's Jim Tankersley on the "what ifs" surrounding the cliff… New NRCC Chairman Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR) on the House GOP's road forward… Democratic strategist Doug Thornell, Roll Call's David Drucker and the New York Times' Jackie Calmes on how the next round of negotiations could be different (or all too similar) to the last time. Advertise | AdChoices *** Friday’s “Jansing & How to Improve Memory E-Cigarettes Exposed: Stony Brook Co.” line-up: MSNBC’s Chris with Scientifically Designed The E-Cigarette craze is sweeping the country.