Paradise Parrot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITES Hooded Parrot Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II [Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)] PERIODIC REVIEW OF PSEPHOTUS DISSIMILIS 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.* 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification to the Parties No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Psephotus dissimilis as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends to maintain Psephotus dissimilis on CITES Appendix I, in accordance with provisions of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev CoP 16) to allow for further review. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 Annex CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

Special Issue: Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution

diversity Editorial Special Issue: Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution Peter Houde Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] Received: 26 September 2019; Accepted: 27 September 2019; Published: 29 September 2019 Abstract: “Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution” is a “state of the art” showcase of the varied and rapidly evolving fields of inquiry enabled and driven by powerful new methods of genome sequencing and assembly as they are applied to some of the world’s most familiar and charismatic organisms—birds. The contributions to this Special Issue are as eclectic as avian genomics itself, but loosely interrelated by common underpinnings of phylogenetic inference, de novo genome assembly of non-model species, and genome organization and content. Keywords: Aves; phylogenomics; genome assembly; non-model species; genome organization Birds have been the focus of pioneering studies of evolutionary biology for generations, largely because they are abundant, diverse, conspicuous, and charismatic [1]. Ongoing individual and extensively collaborative programs to sequence whole genomes or a variety of pan-genomic markers of all 10,135 described species of living birds further promise to keep birds in the limelight in the near and indefinite future [2,3]. Such comprehensive taxon sampling provides untold opportunities for comparative studies in well documented phenotypic, adaptive, ecological, behavioral, and demographic contexts, while elucidating differing characteristics of evolutionary processes across the genome and among lineages [4,5]. “Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution” is a timely snapshot of the rapid ontogeny of these diverse endeavors. It features one review and seven original research articles reflecting an eclectic sample of studies loosely interrelated by common themes of phylogenetic inference, de novo genome assembly of non-model species, and genome organization and content. -

According to Dictionary

Extinction: The Parrots We’ve Lost By Desi Milpacher The definition of extinction is “the act or process of becoming extinct; a coming to an end or dying out: the extinction of a species.” Once extinction has been determined, there is usually no chance of a species recurring in a given ecosystem. In mankind’s active history of exploration, exploitation and settlement of new worlds, there has been much loss of natural resources. Parrots have suffered tremendously in this, with over twenty species having been permanently lost. And there are many more that are teetering on the edge, towards the interminable abyss. In this article we find out what happened to these lost treasures, learn which ones are currently being lost, and why this is important to our world. The Old and New Worlds and Their Lost Parrots Little is known of the natural history of most of the world’s extinct parrots, mainly because they disappeared before in-depth studies were conducted on them. It is generally believed, save the Central American macaws which were least known, that most fed on diets similar to today’s parrots (leaves, blossoms, seeds, nuts and fruits), frequented heavy forested areas and nested mainly in tree cavities. A number could not fly well, or were exceptionally tame, leading to their easy capture. Nearly all of these natural treasures vanished between the 18th and early 20th centuries, and the main reason for their loss was overhunting. Some lesser causes included egg collecting (popular with naturalists in the 19th century), diseases (introduced or endemic), drought, natural disasters, predation by introduced species, and habitat alternation. -

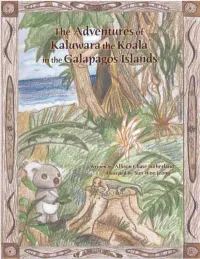

Kaluwara-Excerpt.Pdf

The Adventures of Kaluwara the Koala in the Galapagos Islands Written by Allison Chase Sutherland Illustrated by Sun Woo Jeong The Adventures of Kaluwara the Koala in the Galapagos Islands Copyright © 2006 by Allison Chase Sutherland Washington, DC Summary: Kaluwara the Koala and Kokowara the Kookaburra embark on an adventure of discovery from the eucalyptus forests of Australia to encounter the endangered species of the Galapagos Islands before it’s too late, and teach the children of the Earth how to protect them. Note: Included with the story is a letter from Kaluwara to the children of the Earth, a list of tips to help children protect the environment, and a glossary of English, Spanish, and science terminology. First Edition Printed in USA To Aidan & Marcelo, my favorite albatrosses and my greatest loves!! Thanks to everyone at the Galapagos Conservancy, for reviewing my manuscript, and continuing the important work of protecting the endangered species of the Galapagos. Contents I Francisco the Finch………………………………………….1 II Lolita the Lava Lizard………………………………………..5 III Allie the Albatross – Air Galapagos………………………...8 IV Kokowara the Kookaburra ………………………………...13 V Florentina the Flamingo………….………………………...16 VI Rebecca the Red-footed Booby Bird…………….…………21 VII Aprilita, Alberto, Aidan & Arcelino the Albatrosses….….25 VIII Tortuga the Tortoise……………………………..…….…..29 IX Tortina the Tortoise…….……………………………….…31 X Iggy the Iguana………………………………………..……36 XI Big Tyler the Tortoise & Little Tyler the Tortoise……….…41 XII Pedro the Penguin……………………………………….…45 Letter from Kaluwara……...…………………………….…50 Kaluwara’s 10 Tips to Help Protect the Environment……....51 Photographs of the Author & Illustrator…………….….....53 Note from the Author……………….………………....….54 Glossary - English, Spanish & Science Vocabulary…......…55 ONE Francisco the Finch A strong wind blew the sturdy wooden outrigger Intrepid across the gentle blue Pacific, straight on course to the enchanted islands just emerging from the sea in the distance. -

The Australian Fauna

THE AUSTRALIAN FAUNA BY A. S. LE SOUEF, SYDNEY THE rapidity with which some of the fauna of Australia has been disappearin s beegha n note naturalisty db r somsfo e tim onls i e t yi past t latelbu , y that those interested have been able to get the powers that be to take effective measures for its protection. e wav Th f publieo c sentimen e protectioth e r th fo tf o n wild things tha s passini t g oveworle th s developer dha d strongl e individua th Australian i yl al d l an ,state s which responsible ar welfar e faune th th r f eafo eo have passed good Acts to that end. The administration of these Acts rests in the hands of the police, who, having many other duties to attend to, cannot always follow the matter as closely as could be wished; the work is however gradually becoming more effective, especiall e regulatioth e saln f yth i o e f o n skin protectef so d animals. The enforcement of the State laws, whilst giving the animals and birds scheduled in the Acts adequate protec- tion t allowye , s unrestricted expor anythinf o t gs thawa t i t t founno d necessar protecto y192t n i o lesd n 2 san , than 55,000 birds left for overseas markets. The way in which som thesf eo e birds were lossee packedth d s saian , havo dt e occurred en route, aroused public indignation. Further, the great majority of the birds that arrived alive went into dealers shops, where they had to wait, often in very unhappy conditions, until claimed by a casual purchaser. -

Reviews— Glimpses of Paradise: the Quest for the Beautiful Parrakeet by Penny Olsen, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2007

AUSTRALIAN 102 FIELD ORNITHOLOGY AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2008, 25, 102–108 Reviews— Glimpses of Paradise: The Quest for the Beautiful Parrakeet by Penny Olsen, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2007. Softcover, 22.5 × 25.5 cm, 277 pp, many colour & b/w photos, paintings. RRP $35 (available from BOCA to members for $29.25). Pulcherrimus, the most beautiful. And what a sorry tale is the Paradise Parrot’s, from pathos and tragedy surrounding its entry to science, through early exploitation and wholesale habitat destruction, to more tragedy ending the last authentic records of it, and finally to deceit, skullduggery, criminal activity, denial, self- delusion and fruitless searches in the ensuing decades. It is also part social history, revealing the character of the ‘greats’ and scoundrels in the various periods, and the interconnected circles of acquaintances. This timely and necessary book starts with some apt quotes, among them one from the Monty Python ‘Dead Parrot’ sketch, then provides some background to the book and a tabulated list of major figures in the Parrot’s history. The first three chapters provide a history of John Gilbert’s discovery, and John Gould’s naming, of the species, and the eventual collection and description of the female. Poor Gilbert, robbed of his desired Platycercus gilberti by a combination of unfortunate circumstances. Chapter 4 is an important one critically reviewing the evidence for the Parrot’s true historical distribution, and scotching claims that it occurred on Cape York and in present-day New South Wales (after Queensland separated). Chapter 5 recounts the early live-trapping of the Parrots for European aviculture and nobility. -

First Aboriginal-Led National Recovery Team for Cape York's Endangered

MEDIA RELEASE July 2018 First Aboriginal-led National Recovery Team for Cape York’s endangered Golden-Shouldered Parrot In a positive first for species conservation, Olkola Elder nesting areas that have been impacted by woody Mike Ross has led the reinstated National Recovery thickening. We’ve also undertaken nest surveys which Team meeting for Alwal, the endangered Golden- have improved our understanding of Alwal’s current Shouldered Parrot, on Olkola Country this week. extent of occurrence,” explains Brown. He becomes the first Aboriginal person to Chair a “Nest site surveys are improving our estimates of the National Recovery Team, in acknowledgment of the Northern population and we’ve started a long-term depth of knowledge Aboriginal people have to monitoring program to assess breeding success based contribute to saving species and caring for country. on daily probability of survival, predation, vegetation response to fire management and to further develop This week’s meeting signals a resurgence of the long remote camera survey techniques.” term commitment and resolve to protect Alwal forever. There has not been an active Recovery Team in place About the Golden-Shouldered Parrot for this species since 2003. The budgerigar-sized parrot that nests in termite mounds is a totem of northern Australia’s Olkola people Olkola Aboriginal Corporation Chair Mike Ross said his and known as Alwal in Olkola language. The bird is on appointment was significant and an important step the IUCN’s Red List and listed as endangered by the forward. Queensland and Australian governments. The closest relative of the Golden-shouldered Parrot is the now- “Our job is to link our traditional knowledge and cultural extinct paradise parrot once found in southeast knowledge with the scientific way – there is a pathway Queensland. -

Conservation Advice Psephotus Chrysopterygius Golden

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister’s delegate approved this Conservation Advice on 13/07/2017 . Conservation Advice Psephotus chrysopterygius golden–shouldered parrot Conservation Status Psephotus chrysopterygius (golden–shouldered parrot) is listed as Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act effective from the 16 July 2000. The species is eligible for listing as prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as Endangered under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). Species can also be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl The main factors impacting on the species that are considered to be the cause for its eligibility for listing in the Endangered category are its restricted extent of occurrence that is continuing to decline due to degradation of habitat quality through invasive ti-trees associated with a decline in nest density. Description The golden-shouldered parrot measures 240-260mm in length including its long tapered tail. Like most parrots it is brilliantly coloured, especially the male which is primarily turquoise with a salmon pink belly and bronze wings boasting a streak of bright yellow. The bronze extends to some of its tail feathers, with the rest being black like its crown. Females and immature birds are mostly various shades of green with a turquoise rump (DEHP 2016). The male is turquoise with a black crown, bright yellow on the wing and forehead and with a salmon pink belly. -

Australian Checklist 2008

AUSTRALIAN CHECKLIST 2008 This Australian Checklist, compiled by Lloyd Nielsen, covers the Australian mainland and Tasmania. It does not cover the Australian political island territories, some of which have little affinity with Australian bird species. It can be copied for personal use only, and should be printed in its entirety. This checklist incorporates the latest taxonomic opinions and developments, using the following references: Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds Les Christidis & Walter E Boles 2008 The Directory of Australian Birds Passerines R Schodde & I J Mason 1999 Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds Volumes 1-7 Handbook of Western Australian Birds Volumes 1& 2 R E Johnstone & G M Storr 1998-2004 Endemics are printed in bold [V] = Vagrant [RV] = Rare visitor [H] = Hybrid [I] = Introduced [Extinct] Order now follows the order of Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds Les Christidis & Walter E Boles 2008, officially adopted by Birds Australia. Some taxons previously regarded as a full species no longer appear on the list e.g. Lesser Sooty Owl is now regarded as a subspecies of Sooty Owl. Gould’s Bronze-Cuckoo is now regarded as a subspecies within the Little Bronze-Cuckoo complex. Cox’s Sandpiper is now known to be a natural hybrid between Pectoral and Curlew Sandpipers. -

Australian Parakeets

Australian Parakeets by Warwick Remington Ballarat, Victoria, Australia j ohn Gould is regarded by many as Unlike American and English avi hobby in Australia. the father of ornithology in Australia. culturists, Australians are fortunate to be Intestinal worms have been a prob In 1839 he wrote of our parrots "no able to keep native species in captivi lem with aviary birds for many years. The group of birds gives Australia so foreign ty under license. high susceptibility of Australian par an air as the numerous species of this Many species are now bred in such rots to this problem was first recognized great family each and all of which are numbers that disposal of excess birds in the 1960s. Most Australian species, with very abundant." can be difficult. Some aviculturists now the exception oflorikeets and some cock This statement is largely true today choose not to breed from the com atoos, are ground feeding birds. When with most parrot species being found mon species as there is no demand for kept in confinement (often in damp in good numbers in the wild. However youngsters bred. Ironically, species aviaries) the likelihood ofworm infes two species, the Night Parrot and the such as the Princess Parrot and the tation is very high. The popularity of Paradise Parrot, do verge on the brink Scarlet-chested Parrot, which are two of Australian parrots worldwide in the ofextinction. Some would argue that the Australia's rarest species in the wild, fit 1960s and the 1970s probably stimulated Paradise Parrot has already gone the way into this category. -

Alec Chisholm and the Extinction of the Paradise Parrot

CSIRO PUBLISHING Historical Records of Australian Science, 2021, 32, 156–167 https://doi.org/10.1071/HR20019 Alec Chisholm and the extinction of the Paradise Parrot Russell McGregor College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld 4811, Australia. Email: [email protected] Rediscovered in 1921 after several decades of feared extinction, the resurrection of the Paradise Parrot was brief. Within a few decades more, the parrot was actually extinct, making it the only mainland Australian bird species known to have suffered that fate since colonisation. This article explores the reasons for the paucity and ineffectuality of attempts to preserve the species in the interwar years. By examining the contemporary state of ornithological knowledge on endangered species and the limited repertoire of conservationist strategies then available, the article extends our understanding of early twentieth-century discourses on avian extinction in Australia. It also offers an assessment of the conservationist efforts of Alec Chisholm, an amateur ornithologist who had a major role in the rediscovery of the Paradise Parrot and in subsequently publicising its plight. Published online 12 March 2021 Introduction Manar Park station in August 1929.4 There were some plausible The Paradise Parrot of Australia was first brought to the attention of reports of sightings in the 1930s and 1940s, by Keith Williams, Eric Western science by the zoological collector John Gilbert, who sent a Zillmann and Noel Ensor, although these were retrospective reports 5 skin to his employer, ornithologist John Gould, in 1844. Gilbert was made decades after the events to which they referred. -

January 2021 Pima Animal Care Center Report

Pima Animal Care Center Animal Services Report January 2021 Supporting Pets and People in the community In an effort to expand the services PACC offers the community and in order to create a “shelter without walls”, an extreme shift has been made to support the pets and people within our community by taking more of our services outside the PACC facility. • In January, PACC supported 1,313 pets and their people throughout the community through Keeping Families Together, lost and found reunification, shelter intake, and medical outreach. o PACC took in 1,055 animals, including 474 lost pets and 401 animals surrendered by their owners. o 51 pets received Keeping Families Together funding. o 96 pets were reunited with assistance from our Lost and Found department. o 61 pets received medical care through our medical outreach clinic. o 6 pets that finders were willing to hold onto in their homes until an owner was found. • January officially kicked off our Safety Net Program that provides short-term temporary foster for families experiencing crisis. Currently, 19 pets from 10 homes are in foster homes. o In January, 13 pets from 9 homes were enrolled in the program. 4 due to hospitalization, 1 for first responder support, 2 due to eviction, and 2 due to a house fire; 5 pets from 4 homes have been reunited with their families. • The Pet Support Center received 825 requests for assistance, including 324 requests to rehome a pet, 144 requests for assistance through the Keeping Families Together program, 95 requests for help getting resources for their pet, and 59 requests to assist with accessing euthanasia services.