The Hidden Gulag Second Edition the Lives and Voices of “Those Who Are Sent to the Mountains”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

Like a Magic Trick, the End of the Cold War Fooled and Baffled Its Audience

SS Cold war February 2005 Monotonicity Paradoxes, Mutual Cooperation, and the End of the Cold War: Merging History and Theory Thomas Schwartz• and Kiron K. Skinner♦ February 2005 1 Introduction Like a magic trick, the end of the Cold War fooled and baffled its audience. It happened in full view of scholars and statesmen, yet it flouted all their expectations and left them wondering how and why. Not only why, but why then. If, by 1988 or so, the rulers of Russia saw no profit in projecting power west and south and maintaining a tight grip on Eastern Europe, why had they continued to do just that for so long? And not only how, but who: was Ronald Reagan lucky to be president then, or were we lucky he was president then? Professor Robert Keohane sharpened the puzzle about Ronald Reagan in remarks to Kiron Skinner in the late 1990s: “The assessment [of Ronald Reagan’s presidency] was so bad but the outcome [of the Cold War] was so good.” He then suggested she attempt to marry the historical account she was interested in with a more theoretical analysis of power and cooperation. To this end, she has joined forces with formal theorist Thomas Schwartz of UCLA. • Professor, Department of Political Science, University of California at Los Angeles. ♦ Assistant Professor, Department of Social and Decision Sciences, Carnegie Mellon University, and Research Fellow, Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Skinner is a member of Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s Defense Policy Board and the Chief of Naval Operations Executive Panel. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States government. -

The Contribution of the Afro-Descendant Soldiers to the Independence of the Bolivarian Countries (1810-1826)

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad ISSN: 1909-3063 [email protected] Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Colombia Reales, Leonardo The contribution of the afro-descendant soldiers to the independence of the bolivarian countries (1810- 1826) Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, vol. 2, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2007 Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=92720203 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REVISTA - Bogotá (Colombia) Vol. 2 No. 2 - Julio - Diciembre 11 rev.relac.int.estrateg.segur.2(2):11-31,2007 THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE AFRO-DESCENDANT SOLDIERS TO THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE BOLIVARIAN COUNTRIES (1810-1826) Leonardo Reales (Ph.D. Candidate - The New School University) ABSTRACT In the midst of the independence process of the Bolivarian nations, thousands of Afro-descendant soldiers were incorporated into the patriot armies, as the Spanish Crown had done once independence was declared. What made people of African descent support the republican cause? Was their contribution to the independence decisive? Did Afro-descendant women play a key role during that process? Why were the most important Afro-descendant military leaders executed by the Creole forces? What was the fate of those soldiers and their descendants at the end of the war? This paper intends to answer these controversial questions, while explaining the main characteristics of Recibido: 3 de septiembre 2007 Aceptado: 8 de octubre 2007 society throughout the five countries freed by the Bolivarian armies in the 1810s and 1820s. -

Strangers at Home: North Koreans in the South

STRANGERS AT HOME: NORTH KOREANS IN THE SOUTH Asia Report N°208 – 14 July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. CHANGING POLICIES TOWARDS DEFECTORS ................................................... 2 III. LESSONS FROM KOREAN HISTORY ........................................................................ 5 A. COLD WAR USES AND ABUSES .................................................................................................... 5 B. CHANGING GOVERNMENT ATTITUDES ......................................................................................... 8 C. A CHANGING NATION .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. THE PROBLEMS DEFECTORS FACE ...................................................................... 11 A. HEALTH ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1. Mental health ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Physical health ........................................................................................................................... 12 B. LIVELIHOODS ............................................................................................................................ -

The Korean Internet Freak Community and Its Cultural Politics, 2002–2011

The Korean Internet Freak Community and Its Cultural Politics, 2002–2011 by Sunyoung Yang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Sunyoung Yang Year of 2015 The Korean Internet Freak Community and Its Cultural Politics, 2002–2011 Sunyoung Yang Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2015 Abstract In this dissertation I will shed light on the interwoven process between Internet development and neoliberalization in South Korea, and I will also examine the formation of new subjectivities of Internet users who are also becoming neoliberal subjects. In particular, I examine the culture of the South Korean Internet freak community of DCinside.com and the phenomenon I have dubbed “loser aesthetics.” Throughout the dissertation, I elaborate on the meaning-making process of self-reflexive mockery including the labels “Internet freak” and “surplus (human)” and gender politics based on sexuality focusing on gender ambiguous characters, called Nunhwa, as a means of collective identity-making, and I explore the exploitation of unpaid immaterial labor through a collective project making a review book of a TV drama Painter of the Wind. The youth of South Korea emerge as the backbone of these creative endeavors as they try to find their place in a precarious labor market that has changed so rapidly since the 1990s that only the very best succeed, leaving a large group of disenfranchised and disillusioned youth. I go on to explore the impact of late industrialization and the Asian financial crisis, and the nationalistic desire not be left behind in the age of informatization, but to be ahead of the curve. -

DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DPRK/North Hamgyong Province: Floods Emergency Appeal n° MDRKP008 Glide n° FL-2016-000097-PRK Date of issue: 20 September 2016 Date of disaster: 31 August 2016 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Point of contact: Marlene Fiedler Pak Un Suk Disaster Risk Management Delegate Emergency Relief Coordinator IFRC DPRK Country Office DPRK Red Cross Society Operation start date: 2 September 2016 Operation end date (timeframe): 31 August 2017 (12 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 15,199,723 DREF allocation: CHF 506,810 Number of people affected: Number of people to be assisted: 600,000 people Direct: 28,000 people (7,000 families); Indirect: more than 163,000 people in Hoeryong City, Musan County and Yonsa County Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The State Committee for Emergency and Disaster Management (SCEDM), UN Organizations, European Union Programme Support Units A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster From August 29th to August 31st heavy rainfall occurred in North Hamgyong Province, DPRK – in some areas more than 300 mm of rain were reported in just two days, causing the flooding of the Tumen River and its tributaries around the Chinese-DPRK border and other areas in the province. Within a particularly intense time period of four hours in the night between 30 and 31 August 2016, the waters of the river Tumen rose between six and 12 metres, causing an immediate threat to the lives of people in nearby villages. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

Thank You, Father Kim Il Sung” Is the First Phrase North Korean Parents Are Instructed to Teach to Their Children

“THANK YOU FATHER KIM ILLL SUNG”:”:”: Eyewitness Accounts of Severe Violations of Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion in North Korea PPPREPARED BYYY: DAVID HAWK Cover Photo by CNN NOVEMBER 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Michael Cromartie Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chair Nina Shea Vice Chair Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Khaled Abou El Fadl Dr. Richard D. Land Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Bishop Ricardo Ramirez Ambassador John V. Hanford, III, ex officio Joseph R. Crapa Executive Diretor NORTH KOREA STUDY TEAM David Hawk Author and Lead Researcher Jae Chun Won Research Manager Byoung Lo (Philo) Kim Research Advisor United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Anne Johnson, Director of Communications Christy Klaasen, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Mark Hetfield, Director, International Refugee Issues Eileen Sullivan, Deputy Director for Communications Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Robert C. Blitt, Legal Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Mindy Larmore, Policy Analyst Jacquelin Mitchell, Executive Assistant Tina Ramirez, Research Assistant Allison Salyer, Government Affairs Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Acknowledgements The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom expresses its deep gratitude to the former North Koreans now residing in South Korea who took the time to relay to the Commission their perspectives on the situation in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and their experiences in North Korea prior to fleeing to China. -

The Politics of Memory in Russia

Thomas Sherlock Confronting the Stalinist Past: The Politics of Memory in Russia Attempting to reverse the decline of the Russian state, economy, and society, President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin have paid increasing attention over the past two years to the modernization of Russia’s socioeconomic system. Aware of the importance of cultural and ideological supports for reform, both leaders are developing a ‘‘useable’’ past that promotes anti-Stalinism, challenging the anti-liberal historical narratives of Putin’s presidency from 2000—2008. This important political development was abrupt and unexpected in Russia and the West. In mid—2009, a respected journal noted in its introduction to a special issue on Russian history and politics: ‘‘turning a blind eye to the crimes of the communist regime, Russia’s political leadership is restoring, if only in part, the legacy of Soviet totalitarianism....’’1 In December 2009, Time magazine ran a story entitled ‘‘Rehabilitating Joseph Stalin.’’2 Although the conflicting interests of the regime and the opposition of conservatives are powerful obstacles to a sustained examination of Russia’s controversial Soviet past, the Kremlin has now reined in its recent efforts to burnish the historical image of Josef Stalin, one of the most brutal dictators in history. For now, Medvedev and Putin are bringing the Kremlin more in line with dominant Western assessments of Stalinism. If this initiative continues, it could help liberalize Russia’s official political culture and perhaps its political system. Yet Thomas Sherlock is Professor of Political Science at the United States Military Academy at West Point and the author of Historical Narratives in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). -

Jeju Island Rambling: Self-Exile in Peace Corps, 1973-1974

Jeju Island Rambling: Self-exile in Peace Corps, 1973-1974 David J. Nemeth ©2014 ~ 2 ~ To Hae Sook and Bobby ~ 3 ~ Table of Contents Chapter 1 Flying to Jeju in 1973 JWW Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1, 2013) ~17~ Chapter 2 Hwasun memories (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 2 (January 8, 2013) ~21~ Chapter 3 Hwasun memories (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 3 (January 15, 2013) ~25~ Chapter 4 Hwasun memories (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 4 (January 22, 2013) ~27~ Chapter 5 The ‘Resting Cow’ unveiled (Udo Island Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 5 (January 29, 2013) ~29~ Chapter 6 Close encounters of the haenyeo kind (Udo Island Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 6 (February 5, 2013) ~32~ Chapter 7 Mr. Bu’s Jeju Island dojang (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 7 (February 12, 2013) ~36~ Chapter 8 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 8 (February 19, 2013) ~38~ Chapter 9 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 9 (February 26, 2013) ~42~ Chapter 10 Mr. Bu’s dojang (Part 4) JWW Vol. 1, No. 10 (March 5, 2013) ~44~ Chapter 11 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 1) JWW Vol. 1, No. 11 (March 12, 2013) ~46~ Chapter 12 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 2) JWW Vol. 1, No. 12 (March 19, 2013) ~50~ Chapter 13 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 3) JWW Vol. 1, No. 13 (March 26, 2013) ~55~ Chapter 14 Unexpected encounters with snakes, spiders and 10,000 crickets (Part 4) JWW Vol. -

Analecta Nipponica

5/2016 Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATION FOR JAPANESE STUDIES Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES 5/2016 Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES Editor-in-Chief Alfred F. Majewicz Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Editorial Board Agnieszka Kozyra University of Warsaw, Jagiellonian University in Kraków Iwona Kordzińska-Nawrocka University of Warsaw Editing in English Aaron Bryson Editing in Japanese Fujii Yoko-Karpoluk Editorial Advisory Board Moriyuki Itō Gakushūin University in Tokyo Mikołaj Melanowicz University of Warsaw Sadami Suzuki International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto Hideo Watanabe Shinshū University in Matsumoto Estera Żeromska Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The publication was financed by Takashima Foundation Copyright© 2015 by Polish Association for Japanese Studies and Contributing Authors. ANALECTA NIPPONICA: Number 5/2015 ISSN: 2084-2147 Published by: Polish Association for Japanese Studies Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland www.psbj.orient.uw.edu.pl University of Warsaw Printers (Zakłady Graficzne UW) Order No. 1312/2015 Contents Editor’s preface ...............................................................7 ARTICLES Iijima Teruhito, 日本の伝統芸術―茶の美とその心 .............................11 English Summary of the Article Agnieszka Kozyra, The Oneness of Zen and the Way of Tea in the Zen Tea Record (Zencharoku) .............................................21 -

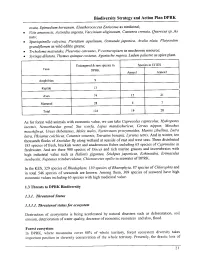

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood.