1 Paediatric Nurses' Knowledge, Attitudes And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microbial Risk Assessment Guideline

EPA/100/J-12/001 USDA/FSIS/2012-001 MICROBIAL RISK ASSESSMENT GUIDELINE PATHOGENIC MICROORGANISMS WITH FOCUS ON FOOD AND WATER Prepared by the Interagency Microbiological Risk Assessment Guideline Workgroup July 2012 Microbial Risk Assessment Guideline Page ii DISCLAIMER This guideline document represents the current thinking of the workgroup on the topics addressed. It is not a regulation and does not confer any rights for or on any person and does not operate to bind USDA, EPA, any other federal agency, or the public. Further, this guideline is not intended to replace existing guidelines that are in use by agencies. The decision to apply methods and approaches in this guideline, either totally or in part, is left to the discretion of the individual department or agency. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2012). Microbial Risk Assessment Guideline: Pathogenic Microorganisms with Focus on Food and Water. EPA/100/J-12/001 Microbial Risk Assessment Guideline Page iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................... ii Interagency Workgroup Members ................................................................................ vii Preface ............................................................................................................................. viii Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. -

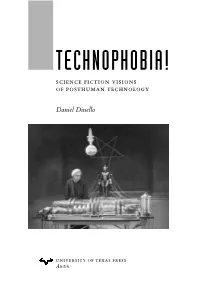

TECHNOPHOBIA! Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology

TECHNOPHOBIA! science fiction visions of posthuman technology Daniel Dinello university of texas press Austin Frontispiece: Human under the domination of corporate science and autonomous technology (Metropolis, 1926. Courtesy Photofest). Copyright © 2005 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First edition, 2005 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819. www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (r1997) (Permanence of Paper). library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Dinello, Daniel Technophobia! : science fiction visions of posthuman technology / by Daniel Dinello. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-292-70954-4 (cl. : alk. paper) — isbn 0-292-70986-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Science fiction—History and criticism. 2. Technology in literature. I. Title. pn3433.6.d56 2005 809.3'876209356—dc22 2005019190 NINE Technology Is a Virus machine plague virus horror: technophobia and the return of repressed flesh Technophiliacs want to escape from the body—that mor- tal hunk of animated meat. But even while devising the mode of their disembodiment, a tiny terror gnaws inside them—virus fear. The smallest form of life, viruses are parasites that live and reproduce by penetrating and commandeering the cell machinery of their hosts, often killing them and moving on to others. ‘‘As the means become available for the technology- creating species to manipulate the genetic code that gave rise to it,’’ says techno-prophet Ray Kurzweil, ‘‘...newvirusescanemergethroughacci- dent and/or hostile intention with potentially mortal consequences.’’1 The techno-religious vision of immortality represses horrific images of mutilated bodies and corrupted flesh that haunt our collective nightmares in the science fiction subgenre of virus horror. -

Pamela: Or, Virtue Reworded: the Texts, Paratexts, and Revisions That Redefine Samuel Richardson’S Pamela

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Pamela: Or, Virtue Reworded: The exT ts, Paratexts, and Revisions that Redefine aS muel Richardson's Pamela Jarrod Hurlbert Marquette University Recommended Citation Hurlbert, Jarrod, "Pamela: Or, Virtue Reworded: The exT ts, Paratexts, and Revisions that Redefine aS muel Richardson's Pamela" (2012). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 194. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/194 PAMELA: OR, VIRTUE REWORDED: THE TEXTS, PARATEXTS, AND REVISIONS THAT REDEFINE SAMUEL RICHARDSON’S PAMELA by Jarrod Hurlbert, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2012 ABSTRACT PAMELA: OR, VIRTUE REWORDED: THE TEXTS, PARATEXTS, AND REVISIONS THAT REDEFINE SAMUEL RICHARDSON’S PAMELA Jarrod Hurlbert, B.A., M.A. Marquette University, 2012 This dissertation is a study of the revisions Samuel Richardson made to his first novel, Pamela, and its sequel, Pamela in Her Exalted Condition, published within his lifetime. Richardson, who was his own printer, revised Pamela eight times over twenty years, the sequel three times, and the majority of the variants have hitherto suffered from critical neglect. Because it is well known that Richardson responded to friendly and antagonistic “collaborators” by making emendations, I also examine the extant documents that played a role in Pamela’s development, including Richardson’s correspondence and contemporary criticisms of the novel. Pamela Reworded, then, is an explanation, exhibition, and interpretation of what Richardson revised, why he revised, and, more importantly, how the revisions affect one’s understanding of the novel and its characters. -

ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 - September 30, 2018)

ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2018 (October 1, 2017 - September 30, 2018) Narrative changes appear in bold text Items underlined have been moved within the guidelines since the FY 2017 version Italics are used to indicate revisions to heading changes The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), two departments within the U.S. Federal Government’s Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) provide the following guidelines for coding and reporting using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). These guidelines should be used as a companion document to the official version of the ICD-10- CM as published on the NCHS website. The ICD-10-CM is a morbidity classification published by the United States for classifying diagnoses and reason for visits in all health care settings. The ICD-10-CM is based on the ICD-10, the statistical classification of disease published by the World Health Organization (WHO). These guidelines have been approved by the four organizations that make up the Cooperating Parties for the ICD-10-CM: the American Hospital Association (AHA), the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), CMS, and NCHS. These guidelines are a set of rules that have been developed to accompany and complement the official conventions and instructions provided within the ICD-10-CM itself. The instructions and conventions of the classification take precedence over guidelines. These guidelines are based on the coding and sequencing instructions in the Tabular List and Alphabetic Index of ICD-10-CM, but provide additional instruction. -

Benzene Poisoning As a Possible Cause of Transverse Myelitis

Paraplegia 22 (1984) 305-310 © 1984 International Medical Society of Paraplegia BENZENE POISONING AS A POSSIBLE CAUSE OF TRANSVERSE MYELITIS By P. HERREGODS, M.D., R. CHAPPEL, M.D. and G. MORTIER, M.D. Service of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Middelheimziekenhuis, Antwerp, Belgium Summary. A case of transverse myelitis in a 25-year-old patient was described. The transverse myelitis was caused by toxic cause, probably as a result of benzene poisoning. This diagnosis was based on: I. The differential diagnosis. 2. The patient's occupation. 3. The abnormal high urinary phenol levels. 4. The coincidence of decreasing urinary phenol values with an amelioration of the clinical condition of patient. After consulting the literature, we think that this case of transverse myelitis based on a benzene poisoning is the first ever described. Key words: Transverse myelitis; Benzene poisoning; Tetraplegia. Case Report A 25-YEAR-OLD warehouseman, working at a wholesale supplier of chemicals and druggist's materials, was admitted into the hospital with the following complaints. In the morning at his work the patient felt an acute inter scapular pain, also radiating down to both arms. Thereafter a progressive paresis of both legs appeared, so that around midday he was unable to rise to his feet. In the afternoon the paresis spread to both upper limbs. At the same time he was unable to urinate spontaneously. This complete picture developed after about 10 hours. There were no medical precedents, neither personal nor in the family. On clinical examination we found a conscious patient in good general condition, temperature 36'2°C, normal pulse, blood pressure 120/70 mmHg, normal heart auscultation and abdominal breathing. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

Medical Thrillers

Medical Thrillers Ablow, Keith Cell 18. Port Mortuary Frank Clevenger Charlatans 19. Red Mist 1. Denial Coma 20. The Bone Bed 2. Projection Death Benefit 21. Dust 3. Compulsion Fatal Cure 22. Flesh & Blood 4. Psychopath Fever 23. Depraved Heart 5. Murder Suicide Genesis 24. Chaos 6. The Architect Godplayer Cotterill, Colin Baden, Michael Harmful Intent Thirty-Three Teeth Manny Manfreda Host Crichton, Michael 1. Remains Silent Invasion Andromeda Strain 2. Skeleton Justice Mindbend The Terminal Man Bass, Jefferson Mortal Fear Cuthbert, Margaret Body Farm Mutation Silent Cradle 1. Carved in Bone Nano Darnton, John 2. Flesh and Bone Pandemic The Experiment 3. The Devil’s Bones Seizure Mind Catcher 4. Bones of Betrayal Shock Delbanco, Nicholas 5. The Bone Thief Sphinx In The Name of Mercy 6. The Bone Yard Terminal Dreyer, Eileen 7. The Inquisitor’s Key Toxin Brain Dead 8. Cut to the Bone Jack Stapleton & Laurie Sinners and Saints 9. The Breaking Point Montgomery With a Vengeance 10. Without Mercy 1. Blindsight Follett, Ken Becka, Elizabeth 2. Contagion The Third Twin Evelyn James 3. Chromosome 6 Whiteout 1. Trace Evidence 4. Vector Gerritsen, Tess 2. Unknown Means 5. Marker Bloodstream Benson, Ann 6. Crisis The Bone Garden Plague Tales 7. Critical Gravity 1. The Plague Tales 8. Foreign Body Harvest 2. The Burning Road 9. Intervention Life Support 3. The Physician’s Tale 10. Cure Jane Rizzoli & Maura Isles Blanchard, Alice 11. Pandemic 1. The Surgeon Life Sentences Marissa Blumenthal 2. The Apprentice Bohjalian, Christopher 1. Outbreak 3. The Sinner The Law of Similars 2. Vital Signs 4. -

Summer Assignments – AP Biology Vincent J. Benitez [email protected]

Summer Assignments – AP Biology Vincent J. Benitez [email protected] http://www.vbbiology.weebly.com 1. Reading Assignment o Choose a book by Robin Cook to read. A list of medical thriller novels is listed below. Dr. Robin Cook is considered to be the master of the medical thriller! He does an enormous amount of research, so all of his books contain good, exciting biology. After reading the book, write a 1-2 page paper containing the following: o Concise summary of the plot. o Highlight the biological aspect(s) of the novel. How does/do the biological aspect(s) play a role in the novel. What technologies/procedures/concepts were used in the novel? o Link the biological aspect(s) of the novel to chapters in the AP Biology textbook. For example, if the book were about a virus, where would you find that topic in the textbook? What other connections can be associated with viruses? Perhaps the immune system, or cells, or biotechnology, etc. List those chapters as well. o Your opinion of the novel. Did you like the book? Did the plot seem too farfetched, or perhaps very plausible? What did you think about how the author used biology to develop interest and carry the story line throughout the book? Book Review Coordinating Instructions o Before writing your book review, read: The Basics of Scientific Writing in APA Style, by Pam Marek. You can find this article at: http://www.macmillanlearning.com/catalog/uploadedfiles/content/worth/custom_solutions/psychology_forew ords/marek_ch04_apastyle_color.pdf. A link to this document is on my website under AP Biology – Articles. -

Pandemic 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 S31 N32

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 Pandemic 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 S31 N32 9780525535331_Pandemic_TX.indd i 8/8/18 2:28 PM 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 Titles by Robin Cook 11 12 Charlatans Contagion 13 Host Acceptable Risk 14 Cell Fatal Cure 15 Nano Terminal 16 Death Benefit Blindsight 17 Cure Vital Signs 18 Intervention Harmful Intent 19 Foreign Body Mutation 20 21 Critical Mortal Fear 22 Crisis Outbreak 23 Marker Mindbend 24 Seizure Godplayer 25 Shock Fever 26 Abduction Brain 27 Vector Sphinx 28 Toxin Coma 29 Invasion The Year of the 30 Intern S31 Chromosome 6 N32 9780525535331_Pandemic_TX.indd ii 8/8/18 2:28 PM 9780525535331_Pandemic_TX.indd iii 8/8/18 2:28 PM 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Pandemic 14 15 16 17 Robin Cook 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS 27 NEW YORK 28 29 30 S31 N32 9780525535331_Pandemic_TX.indd iv 8/8/18 2:28 PM 9780525535331_Pandemic_TX.indd v 8/8/18 2:28 PM 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS Publishers Since 1838 18 An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 375 Hudson Street 19 New York, New York 10014 20 21 22 Copyright © 2018 by Robin Cook Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, 23 promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. -

Risk of Leukemia After Dengue Virus Infection

Published OnlineFirst February 12, 2020; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1214 CANCER EPIDEMIOLOGY, BIOMARKERS & PREVENTION | RESEARCH ARTICLE Risk of Leukemia after Dengue Virus Infection: A Population-Based Cohort Study Yu-Wen Chien1,2, Chia-Chun Wang3, Yu-Ping Wang1, Cho-Yin Lee4,5, and Guey Chuen Perng6,7,8 ABSTRACT ◥ Background: Infections account for about 15% of human cancers Results: We identified 12,573 patients with dengue and 62,865 globally. Although abnormal hematologic profiles and bone mar- non-dengue controls. Patients with dengue had a higher risk of row suppression are common in patients with dengue, whether leukemia [adjusted HR, 2.03; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.16– dengue is associated with a higher risk of leukemia has not been 3.53]. Stratified analyses by different follow-up periods showed investigated. that dengue virus infection was significantly associated with a Methods: We conducted a nationwide population-based higher risk of leukemia only between 3 and 6 years after infection cohort study by analyzing the National Health Insurance (adjusted HR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.25–8.32). There was no significant Research Databases in Taiwan. Laboratory-confirmed dengue association between dengue and the risk of other cancers. patients between 2002 and 2011 were identified; five matched Conclusions: This study provides the first epidemiologic non-dengue controls were randomly selected for each patient. evidence for the association between dengue virus infection and Follow-up ended on December 31, 2015. Multivariate Cox leukemia. proportional hazard regression models were used to evaluate Impact: Considering the rapidly increasing global incidence of the effect of dengue virus infection on the risk of leukemia. -

Medical Thrillers

Medical Thrillers Ablow, Keith Cell 20. The Bone Bed Frank Clevenger Charlatans 21. Dust 1. Denial Coma 22. Flesh & Blood 2. Projection Death Benefit 23. Depraved Heart 3. Compulsion Fatal Cure 24. Chaos 4. Psychopath Fever Cotterill, Colin 5. Murder Suicide Godplayer Thirty-Three Teeth 6. The Architect Harmful Intent Crichton, Michael Baden, Michael Host Andromeda Strain Manny Manfreda Invasion The Terminal Man 1. Remains Silent Mindbend Cuthbert, Margaret 2. Skeleton Justice Mortal Fear Silent Cradle Bass, Jefferson Mutation Darnton, John Body Farm Nano The Experiment 1. Carved in Bone Pandemic Mind Catcher 2. Flesh and Bone Seizure Delbanco, Nicholas 3. The Devil’s Bones Shock In The Name of Mercy 4. Bones of Betrayal Sphinx Dreyer, Eileen 5. The Bone Thief Terminal Brain Dead 6. The Bone Yard Toxin Sinners and Saints 7. The Inquisitor’s Key Jack Stapleton & Laurie With a Vengeance 8. Cut to the Bone Montgomery Follett, Ken 9. The Breaking Point 1. Blindsight The Third Twin 10. Without Mercy 2. Contagion Whiteout Becka, Elizabeth 3. Chromosome 6 Gerritsen, Tess Evelyn James 4. Vector Bloodstream 1. Trace Evidence 5. Marker The Bone Garden 2. Unknown Means 6. Crisis Gravity Benson, Ann 7. Critical Harvest Plague Tales 8. Foreign Body Life Support 1. The Plague Tales 9. Intervention The Bone Garden 2. The Burning Road 10. Cure Jane Rizzoli & Maura Isles Blanchard, Alice Marissa Blumenthal 1. The Surgeon Life Sentences 1. Outbreak 2. The Apprentice Bohjalian, Christopher 2. Vital Signs 3. The Sinner The Law of Similars Cordy, Michael 4. Body Double Midwives Crime Zero 5. Vanish Bova, Ben The Miracle Strain 6. -

The Implicated and the Immune: Cultural Responses to AIDS

The Implicated and the Immune: Cultural Responses to AIDS RICHARD GOLDSTEIN The Village Voice HEN AIDS FIRST PENETRATED AMERICAN consciousness back in 1981, few cultural critics were pre pared to predict that this epidemic would have a broad and W deep impact on the arts. But nine years later, it is possible to argue that virtually every form of art or entertainment in America has been touched by AIDS. Every month, it seems, more is added to the oeuvre of art, dance, music and fiction inspired by the current crisis. Not even tuberculosis, that most literary of epidemics, produced a comparable outpouring in so short a time. Though epidemics have played a major role in shaping American so ciety, artistic production in response to devastating periodic outbreaks of yellow fever, cholera, and influenza (not to mention consumption) has been few and far between. There is no great American novel about the “Spanish Lady” that killed millions in the years following World War I; no revered poem or play commemorating the evacuation of a major American city due to rampaging disease; no major motion pic ture about the polio epidemic that swept the nation in the 1950s. Nothing in American literature is comparable to the preoccupation with pestilence that had inspired great works of European realism by writers as diverse as Defoe, Ibsen, Mann, and Camus. Taken as a whole, American culture’s response to epidemics—from Edgar Allen Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death” to Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith and The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 68, Suppl. 2, 1990 © 1990 Milbank Memorial Fund 2-95 2.96 Richard Goldstein Hollywood melodramas like Jezebel—has been romantic and didactic.