The Stardust Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dublin 9, Ireland

DAIICHI SANKYO IRELAND LTD. TEL: 00 353 (0) 1 4893000 Unit 29, Block 3 FAX: 00 353 (0) 1 4893033 Northwood Court, www.daiichi-sankyo.ie Santry, Dublin 9, Ireland Travel Information M1 From the city centre Follow the signs for Dublin Airport/M1. Once you join the dual carriageway at Whitehall, proceed N1 towards the airport. From this road take the second exit, signed for Santry/Coolock/Beaumont. N3 Once at the top of the exit ramp take a left towards Santry. Continue to the t-junction and once Dublin Airport there, you will see a public park ahead. Take a right-hand turn and proceed past the National We Are Running (Morton) Stadium. The Swords Road entrance for Northwood Business Campus is on your left-hand side. Proceed to the first roundabout and take first exit and take first right. Take second Here M1 left for our car park. R104 From other parts of Dublin Leixlip M50 R807 Follow the signs for the M50. If coming from the south or west, take the northbound route M4 towards the airport. Proceed towards Exit 4, signposted as Ballymun/Naul. Follow signs from the N4 Dublin motorway for Ballymun. Once at the bottom of the exit ramp you will see a slip road to your left, with the Northwood Business Campus entrance directly ahead. Enter the business campus and go Irish Sea straight through the first roundabout (a retail park will be on your left). Take the first right. M50 Entrance to the car park is on the third right. N11 Dalkey Clane N7 N81 By Air R119 Dublin Airport is just 2km from Northwood Business Campus. -

Inspectors Report (308/R308451.Pdf, .PDF Format 301KB)

Inspector’s Report ABP308451-20 Development Construction of a 3 storey, 3-bed dwellinghouse. Location Site to the side of 72 Brookville Park, Coolock, Dublin 5, D05Y766. Planning Authority Dublin City Council. Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 3120/20. Applicant Lina Ivanovaite. Type of Application Permission. Planning Authority Decision Refuse. Type of Appeal First Party. Appellant Lina Ivanovaite. Observer Yvonne Stacey. Date of Site Inspection 28th January 2021 Inspector Paul Caprani. ABP308451-20 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 23 Contents 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Site Location and Description .............................................................................. 3 3.0 Proposed Development ....................................................................................... 4 4.0 Planning Authority’s Decision .............................................................................. 5 4.1. Planning Authority’s Assessment .................................................................. 6 5.0 Planning History ................................................................................................... 7 6.0 Grounds of Appeal ............................................................................................... 8 7.0 Observations...................................................................................................... 11 8.0 EIAR Screening Determination ......................................................................... -

Chapter 13 Cultural Heritage.Pdf

FIGURE 13.1 SHOWING THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT AREA AND NEAREST RMP SITES. ...................... 13-10 FIGURE 13.2 EXTRACT FROM OS 6” FIRST EDITION MAP SHOWING SUBJECT SITE. ................................. 13-14 FIGURE 13.3 EXTRACT FROM OS 25” THIRD EDITION MAP SHOWING SUBJECT SITE. .............................. 13-15 FIGURE 13.4 EXTRACT FROM THE CASSINI MAP OF C. 1940 SHOWING SUBJECT SITE. ............................ 13-15 FIGURE 13.5 AERIAL IMAGE OF THE SITE. ............................................................................................ 13-16 FIGURE 13.6 PREVIOUS FIELDWORK IN THE VICINITY OF THE SITE.......................................................... 13-19 FIGURE 13.7 ACA'S AND HISTORIC LANDSCAPES AND GARDENS IN THE VICINITY OF THE PDA ............... 13-22 FIGURE 13.8 ORDNANCE SURVEY MAP SHOWING LOCATION OF SITE ©OSI ........................................... 13-22 TABLE 13.1 LOCATION DETAILS ............................................................................................................ 13-7 TABLE 13.2 RELEVANT SMR’S IN THE VICINITY OF THE SUBJECT AREA. ................................................ 13-11 TABLE 13.3 RELEVANT RECORDS FROM TOPOGRAPHICAL FILES OF THE NMI ....................................... 13-17 TABLE 13.4 PREVIOUS EXCAVATIONS ................................................................................................. 13-19 TABLE 13.5 TOPONYMS ...................................................................................................................... 13-20 TABLE -

Oscar Traynor Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 Key Features

FOR SALE On the instructions of Mondelez Approx. 2.57 Ha (6.36 Acres) Oscar Traynor Road, Coolock, Dublin 17 Key Features • Approx. 2.57 Ha (6.36 Acres) of Z6 zoned land superbly located on Oscar Traynor Road (frontage approx. 120 m) • Greenfield site strategically situated alongside Northside Retail Park • Title: Freehold • Approx. 7 km north east of Dublin City centre and 4 km south east of Dublin Airport and M50 • Adjacent to quality bus corridor • Suitable for a wide range of commercial and residential uses subject to planning permission • Zoned Z6 Location The subject property occupies a prominent site to the west of the landmark Cadburys factory (Mondelez own Cadburys) at Oscar Traynor Road. It lies approximately 7 km north east of Dublin City centre and approximately 4 km south east of Dublin Airport. The surrounding area has high-density public and private residential housing along with a vast array of commercial amenities with notable nearby occupiers including Aldi, a Tesco Superstore, Bank of Ireland, Odeon Coolock, Leisureplex Coolock and Burger King. The area has strong transport links with the M50/N1 junction and Dublin Port Tunnel situated approx. 2.5 km to the north west. Numerous Dublin Bus routes also pass through Oscar Traynor Road and Old Malahide Road including bus no.’s 17A, 15, 42 and 43. The subject property is also located approx. 1.7 km north east of Harmonstown train station which provides easy access to Howth, Bray, Malahide and Greystones. Local amenities within Coolock include Parnells GAA Club, St. Malachys Football Club, Scoil Chaitriona Cailini, Mercy College and Beaumont Hospital to name a few. -

Dublin North Inner City Creating a Place of Hope, Where Young People’S Dreams Are Realised

Young People At Risk YPAR Dublin North Inner City Creating a place of hope, where young people’s dreams are realised YOUNG PEOPLE’S MIND YOUR MIND DIRECTORY OF SERVICES FOR CHILDREN, YOUNG PEOPLE AND THEIR FAMILIES IN THE DUBLIN NORTH INNER CITY YOUNG PEOPLE’S MIND YOUR MIND DIRECTORY OF SERVICES FOR CHILDREN, YOUNG PEOPLE AND THEIR FAMILIES IN THE NORTH INNER CITY Aosóg Aware Belong To Youth Services Crinan Youth Project CDETB Psychological Service Daughters of Charity Community Services Extern HEADSUP.ie Hill Street Family Resource Centre Limited Hope: Hands on Peer Education HSE, Dublin North City & County CAMHS HSE North Strand Mental Health Services Lisdeel Family Centre (formerly Curam) MyMind - Centre for Mental Wellbeing Neighbourhood Youth Project 1 (Nyp1) Neighbourhood Youth Project 2 (Nyp2) Nickol Project (North Inner City Keeps on Learning) Ozanam House Resource Centre Primary Care Psychology Service Psychotherapy and Counselling Services Samaritans of Dublin Sanctuary for Young People Programme S4YP SAOL S.A.S.S.Y (Substance Abuse Service Specific to Youth) SpunOut St. Joseph’s Adolescent and Family Service St. Joseph’s Adolescent Inpatient Unit Swan Youth Service Teen Counselling Service Is Provided By Crosscare Teen-Line Ireland The Talbot Centre Advocacy – Irish Advocacy Network Snug Counselling Service GROW Young Adult Mental Health Services in Dublin North Central General Practitioners in Dublin North Central YPAR | YOUNG PEOPLE’S MIND YOUR MIND Page Aosóg . 1 Aware . 2 Belong To Youth Services . 3 CDETB Psychological Service . 4 Crinan Youth Project . 5 Daughters of Charity Community Services . 6 Extern . 7 HEADSUP.ie . 8 Hill Street Family Resource Centre Limited . -

Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 Block F: 213-227 Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 Block G: 228-238 Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3

North Central Area Office, Northside Civic Centre, Bunratty Road, Coolock, Dublin 17. Oifig Ceantar an Lárthuaiscirt, Ionad Cathartha an Taoibh Thuaidh, Bóthar Bun Raite, An Chúlóg, Baile Atha Cliath 17. T. 01 222 8541 F. 01 877 5851 E. [email protected] 23rd March 2021 Ref: JOS/2782688/2021 The Chairman and Members of North Central Area Committee. Naming & Numbering Proposal for a new residential development on the site of 126 Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3. (195-238 Ashbrook, Clontarf, Dublin 3) This is a new residential development by MKN Property Group on a site known as 126 Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 (DCC Planning Reference 3234/19). The development will consist of 44 apartments in 3 blocks as shown on the attached drawing SM-2021-0112-2. The proposed Naming & Numbering of the development is as follows: Block E: 195-212 Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 Block F: 213-227 Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 Block G: 228-238 Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3 This new apartment development is extending the existing residential development of Ashbrook. The original development was built in the 1990’s and having searched DCC files and following contact with DCC’s Irish Office & Brainse Logainmneacha it appears that the name Ashbrook (in Clontarf) was never formalised. As a result it is now necessary to formalise the name of this estate and we hereby seek approval from the Committee for the name: Ashbrook, Howth Road, Clontarf, Dublin 3. Justification: The Ashbrook development was built in the early 1990’s by MKN Property Group and associated companies and was located on the lands of a house called “Ashbrook”. -

A Guide to Services for Children with Disabilities

A GUIDE TO SERVICES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES Dublin North Local Health Office DUBLIN NORTH LOCAL HEALTH OFFICE INTRODUCTION Welcome This directory is designed to make sure that you clearly understand local services and how to access them. It gives details about specialist services for children with a disability and about general services for all children. We hope that you find the information in the directory useful. We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Health Service Executive staff and other organisations who were involved in developing the directory. 22 A GUIDE TO SERVICES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES CONTENTS Community Services within the Health Services Executive Public Health Nursing [PHN] Community Health Doctors Community Speech and Language Therapy Community Occupational Therapy Community Physiotherapy Primary Care Psychology Child Protection and Welfare Social Work Primary Care Team [PCT] Disability Services Disability Manager Assessment Officer Case Manager and Liaison Officer Early Intervention Team Dental Service Ophthalmology Service Audiology Service Community Childcare Services Family Centres Community Homemaker and Family Support Service Community Development Resource Centres Neighbourhood Youth Projects Services for the Travelling Community Services for Ethnic Minorities, Refugees and Asylum Seekers Child & Adolescent Mental Health Mater CAMHS 3 DUBLIN NORTH LOCAL HEALTH OFFICE CONTENTS Physical and Sensory Disability Services Physical and Sensory Disability Central Remedial Clinic St Joseph’s Centre -

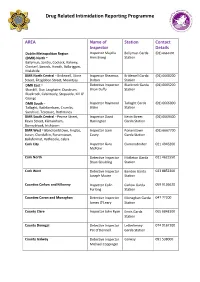

Drug Related Intimidation Reporting Programme

Drug Related Intimidation Reporting Programme AREA Name of Station Contact Inspector Details Dublin Metropolitan Region Inspector Majella Ballymun Garda (01) 6664400 (DMR) North – Armstrong Station Ballymun, Santry, Coolock, Raheny, Clontarf, Swords, Howth, Balbriggan, Malahide DMR North Central – Bridewell, Store Inspector Sheamus Bridewell Garda (01) 6668200 Street, Fitzgibbon Street, Mountjoy Dalton Station DMR East – Detective Inspector Blackrock Garda (01) 6665200 Shankill, Dun Laoghaire, Dundrum, Brian Duffy Station Blackrock, Cabinteely, Stepaside, Kill O’ Grange DMR South – Inspector Raymond Tallaght Garda (01) 6666000 Tallaght, Rathfarnham, Crumlin, Blake Station Sundrive, Terenure, Rathmines DMR South Central – Pearse Street, Inspector David Kevin Street (01) 6669400 Kevin Street, Kilmainham, Harrington Garda Station Donnybrook, Irishtown DMR West – Blanchardstown, Finglas, Inspector Liam Ronanstown (01) 6667700 Lucan, Clondalkin, Ronanstown, Casey Garda Station Ballyfermot, Rathcoole, Cabra Cork City Inspector Gary Gurranabraher 021 4946200 McPolin Cork North Detective Inspector Midleton Garda 021 4621550 Brian Goulding Station Cork West Detective Inspector Bandon Garda 023 8852200 Joseph Moore Station Counties Carlow and Kilkenny Inspector Colin Carlow Garda 059 9136620 Furlong Station Counties Cavan and Monaghan Detective Inspector Monaghan Garda 047 77200 James O’Leary Station County Clare Inspector John Ryan Ennis Garda 065 6848100 Station County Donegal Detective Inspector Letterkenny 074 9167100 Pat O’Donnell Garda Station -

614 Greenogue Business Park.Qxd

International Property Consultants Savills 33 Molesworth Street t: +353 1 618 1300 Dublin 2 e: [email protected] savills.ie For Sale by Private Treaty Prime "Ready To Go" industrial site with superb access to the N7 Site 614, Greenogue Business Park, Co. Dublin Industrial Division • Approx. 1.21 hectares (3 acres) within • Excellent location within minutes of the Contact a well established business location Naas Road (N7), the M50 and the new Gavin Butler, Niall Woods & Stephen Mellon Outer Ring Road (connecting the N4 and the N7) Dublin N7 Naas Baldonnell Aerodrome R120 Aerodrome Business Park Greenogue Business Park For Sale by Private Treaty Site 614 Greenogue Business Park, Co. Dublin M alahide Location Services M50 Sw o rds Railway Portmarnock DART LU A S National Primary Roads Greenogue Business Park is a well- We understand that all mains services M1 Regional Roads N2 Balgriffin Santry Baldoyle Ballym un Sut ton established development located approx. are available and connected to the site. Coolock Beaum ont Howth N3 Blanchardstown Finglas Whitehall Artane Raheny Clonsilla Killester Ashtown Glasnevin 1.1 km from the Rathcoole Interchange on Drum condra M50 Castleknock Marino Clontarf Cabra Phibsborough Fairview Lucan the Naas Road (N7). This interchange is Zoning Palmerstown Chapelizo d N4 Liffey Ringsend Valley Ballyfermot Inchico r e Sandym ount Drimnagh Ballsbridge 8.5 km from the N7 / M50 motorway Under the South Dublin County Council Crum lin Harold's Ranelagh Rathmines Cross Donnybrook Clondalkin Walkinstown Rathgar Kimm age Milltown Blackr ock Te r enure Booterstown Greenhills Rathfarnham junction and is also within close proximity of Development Plan 2004 - 2010 the site is Mount Merrion Monkstown Dun Laoghaire Kilnam anagh Dundrum N7 Te m p leogue Tallaght Stillorgan Sandyford Dalkey Firhouse Deasgrange Ballinteer Saggart Oldbaw n Salynoggi l n the Outer Ring Road which connects the N4 Zoned under Objective EP3 ie."to provide Foxr ock Le opar dstown N81 N11 Edm onstown Cabinteely Killiney to the N7. -

This Includes Dublin North Central

CHO 9 - Service Provider Resumption of Adult Day Services Portal For further information please contact your service provider directly. Last updated 2/03/21 Service Provider Organisation Location Id Day Service Location Name Address Area Telephone Number Email Address AUTISM INITIATIVES IRELAND 2760 AUTISM INITATIVES BOTANIC HORIZONS 202 Botanic Ave, Glasnevin, Dublin 9 Do9y861 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 0831068092 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 2951 CRC - FIRHOUSE Firhouse Shopping Centre, Firhouse, Dublin 24 D24ty24 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-4621826 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 3859 CRC CLONTARF LOCAL CENTRE Penny Ansley Memorial Building, Vernon Avenue, Clontarf Dublin 3 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 8542290 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 3239 CRC COOLOCK LOCAL CENTRE Clontarf, Dublin 3, DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 854 2241 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 2928 CRC HARTSTOWN LOCAL CENTRE Hartstown Local Centre, Hartstown, Blanchardstown Dublin 15 D15t66c NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087-3690502 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 56 CRC RT PROGRAMME Vernon Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-8542396 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 383 CRC-TRAINING & DEV CENTRE Vernon Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3 D03r973 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-8542335 [email protected] CHILD VISION 2388 CHILD VISION Grace Park Road, Drumcondra, Dublin 9 D09wkoh DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01 8373635 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2789 DOC - GLENHILL HOUSE Glenhill House, Finglas, Dublin 11 -D11r85e NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087- 1961476 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2791 DOC - PARNELL COMMUNITY PROGRAMME 40 Parnell Drive, Parnell Estate, Dublin 15 NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087 196 1476 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2920 DOC - ST. -

Main Street, Coolock, Dublin 5

MAIN STREET, COOLOCK, DUBLIN 5 FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY DEVELOPMENT SITE WITH FPP FOR MEDICAL CENTRE AND RETAIL UNIT North Elevation CGI of permitted scheme (For indicative use only) amenities”. The remainder of the site which comprises surface car PLANNING PERMISSION parking is zoned Objective Z9 (Amenity/Open Space Lands/Green The property forms part of a larger grant of planning Network) which is defined as “To preserve, provide and improve permission, (Reference No. 3563/09) for a mixed use scheme. recreational amenity and open space and green networks”. The subject site benefits from planning permission for a three The zoning objective of the subject site remains unchanged in the storey building comprising a ground floor retail unit/pharmacy Draft Dublin City Council Development Plan 2016-2022. and a medical centre on first and second floors, with an overall floor area of approximately 890.7 sq.m (9,586.5 sq.ft). The SCHEDULE OF PERMITTED ACCOMMODATION remainder of the overall development comprises a residential scheme known as Chanel Manor which is partially under Floor Use Size(sq.m) Size (sq.ft) DESCRIPTION construction (comprising 16 no. two storey x 3 bedroom semi- Ground Pharmacy 211.2 2,273.1 detached houses and 1 detached house and 65 apartments in Ground Entrance Lobby 55.6 598.4 East Elevation CGI of permitted scheme two block, one of which adjoins the subject site), a new GAA Ground Plant Room 11.6 124.9 (For indicative use only) The property comprises a topographically Club sports facility and playing fields for Parnell GAA club Ground Bin Store 11.2 120.5 Ground Circulation 8.1 87.2 level regular shaped brownfield site and a which has been completed and a day care centre for St. -

For Sale COOLOCK DRIVE

DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY For Sale COOLOCK DRIVE On the Instruction of the Receiver David Carson COOLOCK, DUBLIN 17, D17 WP28 Danninger (In Receivership) Oscar Traynor Road Cadbury Northside Retail Park Coolock Drive Greencastle Road Boundaries for Indicative Purposes Only PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS • Development / Industrial Site of Approximately 3.55 Ha. / Superb Alternate Use 8.76 Acres • Includes Disused Industrial Facility of 8,981 sq. m. / Development Potential 96,671 sq. ft. • Wide Variety of Uses Permissible or Open for (Subject to P.P.) Consideration Under Zoning Objective • BER No. 800185738 : EPI: 461 VIEWING For further information, please contact joint agents: 01 453 2755 williamharvey.ie THE LOCATION The Property LOCATION MAP • This site is situated on the corner of Greencastle Road and Intending purchasers are specifically advised to verify all information, Coolock Drive with extensive frontage to both. The entrance is including site areas. Aerial photographs are marked for identification accessed off Coolock Drive only 700 metres from Malahide Road. purposes only and for accurate boundaries, purchasers should refer • The junction of the M50 & M1 Motorways is 3.5 km away and Dublin to Title documentation. See DISCLAIMER. International Airport is 7.2 km away. • There is a substantial population in the surrounding area which is OBJECTIVE Z6 ZONING well served by public transport. • This is “To provide for the creation and protection of enterprise • The site is bounded by the extensive Cadbury facility, Northside and facilitate opportunities for employment creation”. Retail Park and a Pitch & Putt Course. • Nearby commercial developments include Coolock • Permissible Uses Include: Retail Park, Odeon Cinema and Leisureplex complex, Clarehall ATM, Betting Office, Car park, Childcare facility, Conference Shopping Centre and Northern Cross.