BELAY DEVICE HANDBOOK Climbing Can Be a Fun and Safe Experience – but Only If You Use the Right Belay Device

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Climbing Gym Industry and Oslo Klatresenter As

Norwegian School of Economics Bergen, Spring 2021 Valuation of Oslo Klatresenter AS A fundamental analysis of a Norwegian climbing gym company Kristoffer Arne Adolfsen Supervisor: Tommy Stamland Master thesis, Economics and Business Administration, Financial Economics NORWEGIAN SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS This thesis was written as a part of the Master of Science in Economics and Business Administration at NHH. Please note that neither the institution nor the examiners are responsible − through the approval of this thesis − for the theories and methods used, or results and conclusions drawn in this work. 2 Abstract The main goal of this master thesis is to estimate the intrinsic value of one share in Oslo Klatresenter AS as of the 2nd of May 2021. The fundamental valuation technique of adjusted present value was selected as the preferred valuation method. In addition, a relative valuation was performed to supplement the primary fundamental valuation. This thesis found that the climbing gym market in Oslo is likely to enjoy a significant growth rate in the coming years, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in sales volume of 6,76% from 2019 to 2033. From there, the market growth rate is assumed to have reached a steady-state of 3,50%. The period, however, starts with a reduced market size in 2020 and an expected low growth rate from 2020 to 2021 because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on this and an assumed new competing climbing gym opening at the beginning of 2026, OKS AS revenue is forecasted to grow with a CAGR of 4,60% from 2019 to 2033. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

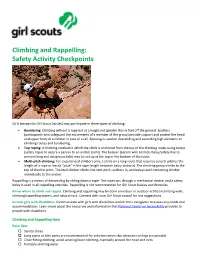

Climbing and Rappelling: Safety Activity Checkpoints

Climbing and Rappelling: Safety Activity Checkpoints Girls (except for Girl Scout Daisies) may participate in three types of climbing: Bouldering: Climbing without a rope but at a height not greater than 6 feet off the ground. Spotters (participants who safeguard the movements of a member of the group) provide support and protect the head and upper body of a climber in case of a fall. Spotting is used on descending and ascending high elements or climbing routes and bouldering. Top roping: A climbing method in which the climb is anchored from the top of the climbing route, using belays (safety ropes to secure a person to an anchor point). The belayer (person who controls belay/safety line to prevent long and dangerous falls) may be set up at the top or the bottom of the route. Multi‐pitch climbing: For experienced climbers only; a climb on a long route that requires several pitches the length of a rope or less (a “pitch” is the rope‐length between belay stations). The climbing group climbs to the top of the first pitch. The lead climber climbs the next pitch, anchors in, and belays each remaining climber individually to the anchor. Rappelling is a means of descending by sliding down a rope. The rope runs through a mechanical device, and a safety belay is used in all rappelling activities. Rappelling is not recommended for Girl Scout Daisies and Brownies. Know where to climb and rappel. Climbing and rappelling may be done on indoor or outdoor artificial climbing walls, climbing/rappelling towers, and natural rock. -

Other Chapters Contents

--------- multipitchclimbing.com --------- This site presents the images from the ebook High: Advanced Multipitch Climbing, by David Coley and Andy Kirkpatrick. In order to keep the cost of the book to a minimum most of these were not included in the book. Although they work best when used in conjunction with the book, most are self-explanatory. Please use the following links to buy the book: Amazon USA (kindle) / Amazon UK (kindle) / itunes / kobo Back to Other Chapters Contents 1. Fall Factors / 2. Dynamic Belaying / 3 The 3-5-8 Rule / 4. Belay Device and Rope Choice / 5. Forces Depend on Angles / 6. Failing Daisies / 7. How Fast Do You Climb? / 8. What is a kN? / 9. What is a “Solid” Placement? / 10. A simple mathematical model of a climbing rope / 11. The problem with high energy falls In this chapter we expand on the basic idea of fall factors to account for rope drag, look at testing data from Petzl and Beal on real-word falls, consider if the angles between the arms of a belay really matters that much, look at how your daisy might kill you, introduce a unit of climbing speed (the Steck), discuss what the “kN” on the side of your carabiners means, present one way of defining just what is a solid placement and introduce a simple mathematical model of a rope. 1. Fall Factors The longer the fall the more energy that needs to be absorbed by the rope. The fall factor provides a useful way of distinguishing between falls of equal length (and therefore equal energy) but that have different amounts of rope out to soak up the energy of the fall. -

Kitsap Basic Climbing

! KITSAP MOUNTAINEERS BASIC CLIMBING COURSE Class 4 and Field Trips 4 & 5 BASIC CLIMBING - CLASS #4 ROCK CLIMBING Class #4 Topics Rock Climbing Process Rock Climbing Techniques Anchors Field Trip Leader Q & A (Field Trip 4) Assigned Reading (complete prior to Class #4) Assigned Reading: Freedom Of The Hills Subject Alpine Rock Climbing ...............................................................Ch 12 Basic Climbing Course Manual All Class #4 Material Additional Resources Find a good book on stretching exercises—it is helpful to loosen up before rock climbing. ROPED CLIMBING OVERVIEW Roped climbing involves the leader and follower(s) attached to a rope for protection as they ascend and descend, so that in the event of a fall the rope can be used to catch the falling climber. In basic rock climbing, the leader is tied into one end of a rope and the follower (second) into the other end. The follower may also attach to a “ground anchor” and will prepare to belay the leader by feeding the rope through his/her belay device. When the follower (belayer) is ready (follower yells: “BELAY ON”), the leader ascends a section of rock (leader: “CLIMBING”, follower: “CLIMB”) while placing protection gear and connecting the climbing rope to the protection as he/she climbs upward. In event of a fall (leader: “FALLING!”), the belayer stops the fall by “braking” the rope at the belay device, and tightening the rope through the protections. When the leader has reached the top of the section (pitch), the leader sets up an anchor and attaches him/ her. The leader tells the follower to take him/her off belay (leader: “OFF BELAY”). -

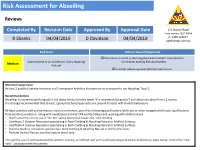

Risk Assessment for Abseiling

Risk Assessment for Abseiling Reviews Completed By Revision Date Approved By Approval Date 171 Nojoor Road Twin waters QLD 4564 P: 1300 122677 R Shanks 04/04/2019 D Davidson 04/04/2019 Apexcamps.com.au Risk level Action required/approval Document controls in planning documents and/or complete this Some chance or an incident or injury requiring Curriculum Activity Risk Assessment. Medium first aid Consider obtaining parental/carer permission. Minimum supervision At least 1 qualified Activity Instructor and 1 competent Activities Assistant are to be present to run Abseiling. Total 2. Recommendations Abseiling is recommended for grade 5 and above for the 6 metre tower. It is recommended grades 7 and above can abseil from 12 metres . It is strongly recommended that at least 1 group teachers/supervisors are present to assist with student behaviours All Apex activities staff and contractors hold at a minimum ,one of the following qualifications /skills sets or other recognised skill sets/ qualifications from another jurisdiction, along with mandatory First Aid/ CPR and QLD Blue Card, working with children check. • Staff trained for correct use of “Gri Gri” safety device that lowers the rock climbing . • Certificate 3 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Certificate 4 Outdoor Recreation specialising in Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Diploma Outdoor recreation specialising is Rock Climbing & Abseiling Natural or Artificial Surfaces • Perform Vertical Rescue also Haul system abseil only. Through the use of well maintained equipment, training, accredited staff and sound operating procedures and policies, Apex Camps control the “real risks” associated with this activity In assessing the level of risk, considerations such as the likelihood of an incident happening in combination with the seriousness of a consequence are used to gauge the overall risk level for an activity. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

Improving Rock Climbing Safety Using a Systems Engineering Approach

Lyle Halliday u5366214 Improving Rock Climbing Safety using a Systems Engineering Approach ENGN2225- Systems Engineering and Design, Portfolio Abstract This portfolio outlines an application of Systems Engineering methods to the sport of Rock climbing. The report outlines an organized, logical analysis of the system that is involved in making this sport safe and aims to improve the system as a whole through this analysis. Steps taken include system scoping, requirements engineering, system function definition, subsystem integration and system attributes which contribute toward a final concept. Two recommendations are made, one being a bouldering mat which incorporates the transportation of other equipment, the other being complete, standardised bolting protocols. These concepts are then verified against the design criteria and evaluated. 1.0 System scoping: A systematic way of establishing the boundaries of the project and focusing the design problem to an attainable goal. The project focuses on Lead Climbing. 2.0 Requirements engineering: Establishing the true requirements of climbers, and what they search for in a climbing safety system 2.1 Pairwise Analysis: Establishing safety, ease of use and durability as primary design goals 2.2 Design Requirements and Technical Performance Measures: Specifying the design requirements into attainable engineering parameters. 2.3 House of Quality: Identifying the trade-offs between safety and functionality/ cost and the need for a whole-of-systems approach to the problem, rather than a component approach. 3.0 System Function Definition: Establishing concepts and system processes. 3.1 Concept Generation and Classification: Identifying possible and existing solutions on a component level and taking these to a subsystem level. -

Belaying » Get It Right!

BeLaYing » get it right! British Mountaineering Council Working for Climbers, hill Walkers and Mountaineers CheCk Harness CheCk KnOT CheCk BeLaY PAY aTTENTiOn! KnOw how to use your gear there are many different ropes and belaying devices available. read and understand the manufacturer’s instructions. if still unsure, get advice from someone more experienced. never belay with equipment you do not know how to use. COnTrol the rOpe Belaying is a complex skill requiring practice and experience to become competent. inattentive belaying is the cause of many preventable climbing accidents. Mistakes can result in serious injuries for climber, belayer or both. Check both climber’s knot and belay device before starting a climb. ensure your rope is long enough for your climb. if in doubt knot the free rope end. Pay attention and keep a controlling hand on the rope. geT in the BesT pOsiTiOn Anticipate the direction of pull, and position yourself appropriately. if you stand near the foot of a climb you are less likely to be pulled off balance when holding a fall or lowering a climber. if there is a lot of rope paid out the climber could hit the ground. Standing near the climb results in less rope between belayer and climber. When the climber is not moving, hold the rope in the locked position. suppOrT BriTisH CLiMBing – jOin THe BMC TOdaY: WWW.THeBMC.Co.uk T: 0161 445 6111 Belay deviCe deSign there are two types of belay device: manual devices and assisted braking devices. A manual device employs mainly friction, allowing some rope slippage when holding a fall. -

California— Yosemite

California— Yosemite: (1) On October 25, 1952 a party composed of Bill Long, Dick Long, A l Steck and William Dunmire (22) set out to attempt an ascent of the El Capitan Buttress (east of the main face). Steck and Dunmire were the first rope of two, and on the third pitch it was Dunmire’s turn to lead. Steck, belaying from a four foot wide ledge, was anchored to a piton and had placed another piton through which he belayed Dunmire. The route led up alongside a vertical crack into which Dunmire placed two pitons, about 6 feet apart. Along this crack was a large block which appar ently was not a part of the cliff but wedged in on one side and the pitons tested soundly, and he felt he had no real reason to doubt their security. Another higher crack failed to be satisfactory for piton use. A spade piton, however, was placed under a somewhat rotten flake. This also was tested. Dunmire warned Steck that the top piton was not too sound. He used it for direct aid to gain a small foothold three feet above. At this point, three feet above the highest piton, twelve feet above the next and and about twenty feet above the belayer, he attempted to place a fourth piton at arms length above him in a horizontal crack under an overhang. While he was hammering his feet slipped and he fell. He fell nearly free, striking the cliff only once and landed on his shoulder and head on a ledge about 15 feet below Steck. -

A Short and Somewhat Personal History of Yukon Glacier Studies in the Twentieth Century GARRY K.C

ARCTIC VOL. 67, SUPPL. 1 (2014) P. 1 – 21 http://dx.doi.org/10.14430/arctic4355 A Short and Somewhat Personal History of Yukon Glacier Studies in the Twentieth Century GARRY K.C. CLARKE1 (Received 7 January 2013; accepted in revised form 22 July 2013; published online 21 February 2014) ABSTRACT. Glaciological exploration of Yukon for scientific purposes began in 1935, with the National Geographic Society’s Yukon Expedition led by Bradford Washburn and the Wood Yukon Expedition led by Walter Wood. However, Project “Snow Cornice,” launched by Wood in 1948, was the first expedition to have glacier science as its principal focus. Wood’s conception of the “Icefield Ranges Research Project” led the Arctic Institute of North America (AINA) to establish the Kluane Lake Research Station on the south shore of Kluane Lake in 1961. Virtually all subsequent field studies of Yukon glaciers were launched from this base. This short history attempts to document the trajectory of Yukon glacier studies from their beginnings in 1935 to the end of the 20th century. It describes glaciological programs conducted from AINA camps at the divide between Hubbard Glacier and the north arm of Kaskawulsh Glacier and at the confluence of the north and central arms of Kaskawulsh Glacier, as well as the galvanizing influence of the 1965 – 67 Steele Glacier surge and the inception and completion of the long-term Trapridge Glacier study. Excluded or minimized in this account are scientific studies that were conducted on or near glaciers, but did not have glaciers or glacier processes as their primary focus. -

Karabiner Breakings When Using a Figure-Of-Eight Neville Mcmillan

Karabiner Breakings when Using a Figure-of-Eight Neville McMillan Introduction cently, the same mode of karabiner fail- held roughly horizontally whilst abseil- ure has occurred due to the levering ac- ing. At the start of an abseil, when the or decades climbers have been us- tion of an energy absorbing system (see rope is more horizontal than vertical, ing a Figure-of-Eight (Foe) as article by Charlet). depending on the orientation of the kar- F standard equipment for abseiling. abiner, this can allow the FoE to apply a Both experts and complete novices The First Failure – a Lucky Escape large force to the gate of the karabiner, have used this piece of equipment, in- and lever it open, breaking a notch out variably attached to their harness or A climber had set up an anchor point of the locking-sleeve (see Fig. 1). waist belt by a screwgate karabiner, for top-roping at the top of a single It is thought that this happened at the without any reported problems. Yes, pitch route. He then prepared himself start of this abseil, though the climber there have been many abseiling acci- for abseiling to the ground. He wore a did not realise it at the time. A little fur- dents, due to an inadequate anchor point, or the rope getting cut, or abseil- ing off the end of the rope, or losing control of the free end of the rope, etc, etc. But until five years ago there had not been any reported failures of the Figure-of-Eight (FoE) or its attachment karabiner.