Triassic Cratered Cobbles: Shock Effects Or Tectonic Pressure? M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Shinarump No. 1 Uranium Mine, Seven Mile Canyon Area, Grand County, Utah

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 336 GEOLOGY OF THE SHINARUMP NO. 1 URANIUM MINE, SEVEN MILE CANYON AREA, GRAND COUNTY, UTAH This report concerns work done on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 336 GEOLOGY OF THE SHINARUMP NO. 1 URANIUM MINE, SEVEN MILE CANYON AREA, GRAND COUNTY, UTAH By W. L Pinch This report concerns work done on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission. __________Washington, D. C., 1954 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. , B E A V E R * 'IRON .-'I GAR WASHINGTON L K«n«b'p U A.R I EXPLANATION Uranium deposit or group of deposits in the Shinarump conglomerate Uranium deposit or group of deposits in the Chfnle formation 25 0 I i i i i I Figure 1. Map of part of the Colorado Plateau showing the location of the Shinarump No. 1 mine and the distribu tion of uranium deposits in the Shinarump and Chinle formations. GEOLOGY OF THE SHINARUMP NO. 1 URANIUM MINE, SEVEN MILE CANYON AREA, GRAND COUNTY, UTAH By W. I. Finch CONTENTS Page Page Abstract..................................... 1 History and production........................ 4 Introduction.................................. 2 Ore deposits................................. 4 General geology............................... 2 Mineralogy.................................. 5 Stratigraphy............................. 2 Petrology.................................... 6 Stratigraphic section................ 2 Habits of ore bodies .......................... 9 Cutler formation.................... 3 Spectrographic study.......................... 10 Moenkopi formation................. 3 Age determinations of uraninite............... -

Triassic Stratigraphy of the Southeastern Colorado Plateau, West-Central New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/72 Triassic stratigraphy of the southeastern Colorado Plateau, west-central New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, 2021, pp. 229-240 in: Geology of the Mount Taylor area, Frey, Bonnie A.; Kelley, Shari A.; Zeigler, Kate E.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Goff, Fraser; Ulmer-Scholle, Dana S., New Mexico Geological Society 72nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 310 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2021 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, Color Plates, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Utah Geology: Making Utah's Geology More Accessible. View South-East

5/28/13 Utah Geology: Geologic Road Guides Utah Geology: Making Utah's geology more accessible. View south-east over St. George, Utah Road Guide Quick Select. Selection Map HW-160, 163 & 191 Tuba City to Kayenta, Bluff & Montecello, Utah (through Monument Valley) 0.0 Junction of U.S. Highways 160 and 89 , HW-160 Road Guide. follows U.S. Highway 160 east toward Tuba city and Kayenta. U.S. Highway 89 leads south toward the entrance to Grand Canyon National Park and Flagstaff. For a route description along U.S. Highway 89 northward from here see HW-89A Road Guide.. The road junction is in the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle Formation. The member is composed of interbedded stream channel sandstone and varicolored shale and mudstone. This member erodes moderately easily and forms the strike valley to the north and south. From here the route of this guide leads upsection into younger and younger beds of the Chinle Formation. 0.7 Cross Hamblin Wash and rise from the Petrified Forest Member into the pinkish banded Owl Rock Member of the Chinle Formation. The upper member forms pronounced laminated pinkish gray and green badlands, distinctly unlike the rounded Painted Desert-type massive badlands of the underlying member. 1.6 Road rises up through the upper part of the Chinle Formation, a typical wavy to hummocky road. Highway construction is easy across the slope-forming parts of the formation, but holding the road after construction is difficult because the soft volcanic ash-bearing shales heave under load or after wetting and drying. -

Uranium Deposits at Base of the Shinarump Conglomerate Monument Valley Arizona

Uranium Deposits at Base of the Shinarump Conglomerate Monument Valley Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1030-C This report concerns work done on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission Uranium Deposits at Base of the Shinarump Conglomerate Monument Valley Arizona By I. J. WITKIND CONTRIBUTIONS TO ^THE GEOLOGY OF URANIUM GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1030-C This report concerns work done on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 65 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract_______________________________________ __ 99 Introduction and acknowledgments __________________________________ 99 General geology __________ ______ ___________ _____________ 100 Shinarump conglomerate _ _. _____________________ 102 Channels_______________ _______________ _________ _____ _____ __ 103 Appearance.. ________ ___ __________ ______________ ________ 103 Classification. _______ ______________ ____ _ ___ ______________ 104 Trends.______-._ ___ _______ __ 106 Widths_________-__._ _________ _ ___ ____. _____ _ __ ______ 113 Floors_____________________________ _._ __ __ __ ____________ 113 Sediments-___ ______ _ __ __________ _____ _ _____ _ _______ 113 Swales associated with channels_ _ _____ _ _ __ ______________ 115 Origin._______ ____________ __________________________________ 116 Localization of uranium ore in channels_ _ _ _____ __________________ 117 Rods________________ ___________________________________ ____ 119 Summary__________ _____________________ _____ _________ _ _ _. 129 Literature cited. _________ ______________________________________ __ 130 ILLUSTRATIONS [Plates 5, 6 in pocket] PLATE 5. -

GEOLOGY AMD URANIUM DEPOSITS 0$’ the SHINARUMP Congloiverate of NOKAI MESA, ARIZONA and UTAH

Geology and uranium deposits of the Shinarump conglomerate of Nakai Mesa, Arizona and Utah Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grundy, Wilbur David, 1929- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 21:24:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551207 GEOLOGY AMD URANIUM DEPOSITS 0$’ THE SHINARUMP CONGLOivERATE OF NOKAI MESA, ARIZONA AND UTAH by Wilbur David. Grundy A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Geology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1953 Approved: Director of Thesis ^ D a t e V This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, proviaed that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

The Geology of Quail Creek State Park Itself, the Park Is Surrounded by a Landscape of Enormous Geological and Human Interest

TT HH EE G E O L OO GG Y OO FF Q UU AA II LL C R E E K SS T A TT EE PP A R K T H E G E O L O G Y O F Q U A I L C R E E K S T A T E P A R K T H E GEOLO G Y O F Q UA IL CREEK STAT E PA R K by Robert F. Biek Introduction . 1 Layers of Rock. 3 Regional overview . 3 Moenkopi Formation . 4 Shnabkaib Member . 6 Upper red member . 7 Chinle Formation . 7 Shinarump Conglomerate Member . 7 Petrified Forest Member . 8 Surficial deposits . 9 Talus deposits . 9 Mixed river and slopewash deposits . 9 Landslides. 9 The Big Picture . 10 Geological Highlights . .14 Virgin anticline . .14 Faults . .14 Gypsum . .14 “Picture stone” . .15 Boulders from the Pine Valley Mountains . .16 Catastrophic failure of the Quail Creek south dike . .17 Acknowledgments . .19 References . .19 T H E G E O L O G Y O F Q U A I L C R E E K S T A T E P A R K I N T R O D U C T I O N The first thing most visitors to Quail Creek State Park notice, apart from the improbably blue and refreshing waters of the reservoir itself, are the brightly colored, layered rocks of the surrounding cliffs. In fact, Quail Creek State Park lies astride one of the most remarkable geologic features in southwest- ern Utah. The park lies cradled in the eroded core of the Virgin anticline, a long upwarp of folded rock that trends northeast through south-central Washington County. -

Geologic Map of the Twin Rocks Quadrangle

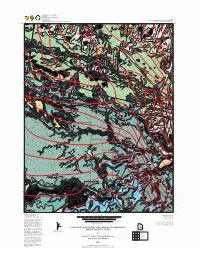

UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of Utah Department of Natural Resources in cooperation with Plate 1 National Park Service Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 07-3 and Brigham Young University Department of Geological Sciences Geologic Map of the Twin Rocks Quadrangle Qe JTRw Qal Qmt Jno Jno Qms Jn JTRw Jno Jk Jn Qe Qe Jn Jn Jpc Jk Jpcr Qe Qmt Qe Jno Jno Jno JTRw Jno Jk Qe Qe Jn Qms Jn Jno Jno Jno Jno Ti 4200 JTRw Jno Jno 4600 4000 Jk Jno W A T E R P O C K E T Jn Qmt Qe Jn Ti Jno Qe 5000 Jno Jn Ti Qms Qms Qms Qmt Qmt Qmt 4400 Jk Jn JTRw Jn Qe Jno Qms Jno Jn Qe Qe Jn Qe Jn Jn Ti Jno Jno Jno Jn Jno Jn Jn Jk JTRw Qe Qmt Jk Jno TRco Qmt JTRw Jno TRco Qmt Jn Jno Qe Qmt TRcm TRco Qmt JTRw Jno Jno TRcp TRcp Jno Qmt Qal Jk Ti Qal Qmt JTRw Jk TRcp TRcp Jno Jn Jn TRcm Qmt Jno TRco Jno 4800 Qmt TRcp TRco Qal C A P I T O L R E E F Jno TRco F O L D Qmt JTRw Jno Qe Jno TRcp Qmt Jn JTRw JTRw Spring Jk Jno JTRw Qmt Jno Jk Jk Qmt Qmt TRco 5 Jn TRco Ti Qmt Qmt Jno Jk Qmt JTRw Canyon R TRco Qmt T co Qe JTRw Qmt R Qe TRco TRco TRco Tco Ti Qmt Qal C A P I T O L Qmt TRco TRco Jk TRco 5800 JTRw Qal JTRw Jno Jk Jno Jno Qmt TRco Qe Qe JTRw Jk Qe Jn Jno Jno Ti Jn JTRw Qmt Jk Jk Jno Jno Jno Jn JTRw Jk 5000 Jno JTRw Jno 4 Qe Qe R A' T co Qmt 5400 Jk Jn Jno 5600 Qe Qe Jno TRcp Qe Jn TRcm Qe Qmt Jno Jno JTRw Qe M E E K S Jn Ti Qe 3 4800 Jno Qe R E E F Jno Jno Qe Qal JTRw Qe Qe Jno Jn Qmt Qe Qe Jk Jk R Jk Jno Jno JT w Qmt Jno Jno TRco M E S A Qmt Jno Jno Qmt Qal Jno Qe Qe Qe Qmt Jk Jn Qmt TRco Qe TRco Jno Jk Qmt Qe Qal JTRw JTRw Jk TRco TRcp TRcp 5200 -

Geologic Map of the Divide Quadrangle Washington County Utah

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE DIVIDE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON COUNTY, UTAH by Janice M. Hayden This geologic map was funded by the Utah Geological Survey and the U.S. Geological Survey, National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, through Statemap Agreement No. 98HQAG2067. ISBN 1-55791-597-0 ,Ill MAP197 I"_.\\ Utah Geological Survey ..,, a division of 2004 Utah Department of Natural Resources STATE OF UTAH Olene S. Walker, Govenor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Robert Morgan, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Richard G. Allis, Director PUBLICATIONS contact Natural Resources Map/Bookstore 1594 W. North Temple telephone: 801-537-3320 toll-free: 1-888-UTAH MAP website: http://mapstore.utah.gov email: [email protected] THE UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY contact 1594 W. North Temple, Suite 3110 Salt Lake City, UT 84116 telephone: 801-537-3300 website: http://geology.utah.gov Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Uah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding its suitability for any particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Sur vey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. The views and conclusions contains in this document are those of the author and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Govemmenrt. The Utah Department of Natural Resources receives federal aid and prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, age, national origin, or disability. For information or complaints regarding discrimination, contact Executive Director, Utah Department of Natural Resources, 1594 West North Temple #3710, Box 145610, Salt Lake City, UT 84JJ6-5610 or Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1801 L Street, MY, Wash ington DC 20507. -

Ferns from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) in the Fort Wingate Area, New Mexico

Ferns From the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) in the Fort Wingate Area, New Mexico GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 613-D Ferns From the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) in the Fort Wingate Area, New Mexico By SIDNEY R. ASH CONTRIBUTIONS TO PALEONTOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 613-D Revision ofJive Late Triassic ferns and a review of previous paleobotanical investigations in the Triassic formations of the Southwest UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price ?1.00 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Summary of pre-Cenozoic stratigraphy Continued !*w Abstract.__________________________________________ Dl Permian System_______-____----__-_-_-----____- D17 Introduction. ______________________________________ 1 Glorieta Sandstone___________-_----____-__ 17 Acknowledgments. _____________________________ 4 San Andres Limestone.____________________ 17 Previous investigations ______________________________ 4 Unconformity between the Permian and Triassic U.S. Army exploring expeditions..________________ 5 rocks._______-_-______-__--_--_-----_--_-_-__ 19 Washington expedition._____________________ 5 Triassic System_______________________________ 19 Sitgreaves expedition._______________________ 5 Moenkopi(?) Formation.____________________ 19 Whipple expedition _________________________ 5 Pre-Chinle -

Revised Stratigraphy of the Lower Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

Parker, W. G., Ash, S. R., and Irmis, R. B., eds., 2006. A Century of Research at Petrified Forest National Park. 17 Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin No. 62. REVISED STRATIGRAPHY OF THE LOWER CHINLE FORMATION (UPPER TRIASSIC) OF PETRIFIED FOREST NATIONAL PARK, ARIZONA DANIEL T. WOODY* Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-4099 * current address: Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder CO 80309 <[email protected]> ABSTRACT— The Sonsela Sandstone bed in Petrified Forest National Park is here revised with specific lithologic criteria. It is raised in rank to Member status because of distinct lithologies that differ from other members of the Chinle Formation and regional distribution. Informal stratigraphic nomenclature of a tripartite subdivision of the Sonsela Member is proposed that closely mimics past accepted nomenclature to preserve utility of terms and usage. The lowermost subdivision is the Rainbow Forest beds, which comprise a sequence of closely spaced, laterally continuous, multistoried sandstone and conglomerate lenses and minor mudstone lenses. The Jim Camp Wash beds overlie the Rainbow Forest beds with a gradational and locally intertonguing contact. The Jim Camp Wash beds are recognized by their roughly equal percentages of sandstone and mudstone, variable mudstone features, and abundance of small (<3 m) and large (>3 m) ribbon and thin (<2 m) sheet sandstone bodies. The Jim Camp Wash beds grade into the overlying Flattops One bed composed of multistoried sandstone and conglomerate lenses forming a broad, sheet-like body with prevalent internal scours. The term “lower” Petrified Forest Member is abandoned in the vicinity of PEFO in favor of the term Blue Mesa Member to reflect the distinct lithologies found below the Sonsela Member in a north-south outcrop belt from westernmost New Mexico and northeastern Arizona to just north of the Arizona-Utah border. -

Geological Society of America Bulletin

Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on January 26, 2010 Geological Society of America Bulletin Post-Paleozoic alluvial gravel transport as evidence of continental tilting in the U.S. Cordillera Paul L. Heller, Kenneth Dueker and Margaret E. McMillan Geological Society of America Bulletin 2003;115;1122-1132 doi: 10.1130/B25219.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geological Society of America Bulletin Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes Geological Society of America Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on January 26, 2010 Post-Paleozoic alluvial gravel transport as evidence of continental tilting in the U.S. -

The Shinarump Member of the Chinle Formation Charles G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/9 The Shinarump Member of the Chinle Formation Charles G. Evensen, 1958, pp. 95-97 in: Black Mesa Basin (Northeastern Arizona), Anderson, R. Y.; Harshbarger, J. W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 9th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 205 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1958 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States.