19 8 9 from Postwar to Postmodern Art in Japan 1945–19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters Micah Holt University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Holt, Micah, "Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2682. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112082 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPLIED ANATOMY IN MUSIC: BODY MAPPING FOR TRUMPETERS By Micah N. Holt Bachelor of Arts--Music University of Northern Colorado 2010 Master of Music University of Louisville 2012 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2016 Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas April 24, 2016 This dissertation prepared by Micah N. -

An Interview with Frieder Nake

arts Editorial An Interview with Frieder Nake Glenn W. Smith Space Machines Corporation, 3443 Esplanade Ave., Suite 438, New Orleans, LA 70119, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 May 2019; Accepted: 26 May 2019; Published: 31 May 2019 Abstract: In this interview, mathematician and computer art pioneer Frieder Nake addresses the emergence of the algorithm as central to our understanding of art: just as the craft of computer programming has been irreplaceable for us in appreciating the marvels of the DNA genetic code, so too has computer-generated art—and with the algorithm as its operative principle—forever illuminated its practice by traditional artists. Keywords: algorithm; computer art; emergent phenomenon; Paul Klee; Frieder Nake; neural network; DNN; CNN; GAN 1. Introduction The idea that most art is to some extent algorithmic,1 whether produced by an actual computer or a human artist, may well represent the central theme of the Arts Special Issue “The Machine as Artist (for the 21st Century)” as it has evolved in the light of more than fifteen thoughtful contributions. This, in turn, brings forcibly to mind mathematician, computer scientist, and computer art pioneer Frieder Nake, one of a handful of pioneer artist-theorists who, for more than fifty years, have focused on algorithmic art per se, but who can also speak to the larger role of the algorithm within art. As a graduate student in mathematics at the University of Stuttgart in the mid-1960s (and from which he graduated with a PhD in Probability Theory in 1967), Nake was a core member, along with Siemens mathematician and philosophy graduate student Georg Nees, of the informal “Stuttgart School”, whose leader was philosophy professor Max Bense—one of the first academics to apply information processing principles to aesthetics. -

2302.Jerome Dretzka Papers

Title: Dretzka, Jerome Papers Reference Code: Mss-2302 Inclusive Dates: 1909-1963 Quantity: 10 cu. ft. Location: NE, Sh. 048-051 OS LG “D” Abstract: Jerome C Dretzka (1881-1963) served on the Milwaukee County Parks Commission from 1920-1963. During that tenure, from 1926-1952, he served as the Executive Secretary of the Commission and expanded the area of Milwaukee parks considerably. He also served as an officer for the American Institute of Park Executives. He retired in 1952. He was born on December 5, 1881 in Pozen, Poland. His family moved to America when he was five years old and they settled on the south side of Milwaukee. In 1893, his family moved to Cudahy where he continued to reside until his death. He served as the city of Cudahy’s city clerk from 1912-1916. He left this position to manage the real estate holdings of Patrick Cudahy. This knowledge served him well during his time on the Commission and during his tenure the Commission went from owning 680 acres to over 7,000 acres of parks. He also served on the boards of the Milwaukee County Historical Society, New Zoo Conference Committee, Wisconsin Park and Recreation Society, as well as many others. Scope and Content: The bulk of the collection consists of material pertaining to Milwaukee County Park Commission and some of the material pertains to his participation in the American Institute of Park Executives (AIPE).In the form of correspondence, newspaper clippings, meeting minutes and official papers from the Commission. This collection also includes information about various projects that he was involved with including the zoo, Mitchell Conservatory, the Braves, and the Milwaukee County Stadium. -

Address by NASA Administrator Sean O'keefe

Remarks by the Honorable Sean O’Keefe NASA Administrator Apollo 11 Anniversary Event Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum July 20, 2004 Good evening ladies and gentlemen. It is a great privilege to be in this shrine to aviation and spaceflight achievement in the presence of America's first great generation of space explorers, those who made their epic voyages possible, and of our current astronauts and the NASA team members who will enable humanity's next momentous steps in space as Dr. Marburger (Presidential Science Advisory Dr. Jack Marburger) just so eloquently discussed. There are so many great friends here from Congress who been very, very important in our quest to make this next great step feasible. Senator Bill Nelson, Congressmen Ralph Hall, Nick Lampson, Sheila Jackson Lee, Mike McIntyre, Mike Pence, Vic Snyder, Dave Weldon, Bob Aderholt, Chairman of 1 the Science Committee Sherry Boehlert, Sam Johnson, Tom Feeney, Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee Chairman Dana Rohrabacher and Juliane Sullivan who is here representing Majority Leader Tom DeLay. We are delighted for their participation, their help, their enthusiasm for I think the importance of this evening's event, as well as for our continued quest forward. I doubt there are any historical parallels to our good fortune here. Certainly, no records exist of people living in Lisbon 500 years ago attending a candlelit tribute to Amerigo Vespucci, Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan, who was about to set forth on his voyage to circle the globe. Yet here we are, in the midst of another great age of exploration, thrilled to have under one roof so many heroes who've sailed over the far horizon to the shores of space and back, including to a dusty Sea named Tranquility. -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

Toward a Theological Response to Prostitution: Listening to the Voices of Women Affected by Prostitution and of Selected Church Leaders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Middlesex University Research Repository Toward a Theological Response to Prostitution: Listening to the Voices of Women Affected by Prostitution and of Selected Church Leaders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Jennifer Andrea Singh OCMS, Ph.D. August 2018 ABSTRACT This feminist, qualitative research project explores how the voices of women affected by prostitution in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and of selected evangelical church leaders in that city, could contribute to a life- affirming theological response to prostitution. The thesis engages sociological and theological sources to interpret the data gathered; contextual Bible study sessions provided access to the women’s voices, and semi-structured interviews revealed church leaders’ perspectives. During conversations with the women, six core themes emerged, reflecting their contextual understanding of the social and theological ramifications of prostitution: their entrance into prostitution; God; sin; humanity (Christian anthropology); justice; and the church. The women articulated that: 1) prostitution was a means of survival; 2) God is a protective figure in their lives; 3) sin is equated with prostitution and uncleanliness; 4) humanity is rejecting; 5) injustice is a normalised experience; and 6) they are unwelcome in the church due to their status as ‘sinners,’ and have few expectations that the Christian church or its leaders would help them exit prostitution. These themes reportedly resonated with interviewed church leaders, who expressed empathy for the women. Bringing both sets of voices together in a discussion of the Story of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32), however, revealed several theological deficiencies held by the evangelical church that currently impede the formation of a life-affirming theological response to prostitution. -

Destruction Requirements for State Records, Canceled Checks & Electronic Images

EXHIBIT H Page 1 of 2 DIVISION OF MEDICAL ASSISTANCE AND HEALTH SERVICES (DMAHS) MEDICAL ASSISTANCE DISBURSEMENT SERVICES RFP 2012 Destruction Requirements for State Records, Canceled Checks & Electronic Images The NJ Department of State’s Division of Archives and Record Management (NJDARM) is responsible for insuring that all public records are managed, preserved and destroyed in accordance with public law. Destruction of Canceled Checks The bank must destroy all public documents in accordance with state regulations and the retention schedule promulgated by NJDARM in consultation with the appropriate State agency and approved by the State Records Committee (SRC). The records retention schedule for the purposes of this bid is S820300-002-0048-0000: Canceled Checks. Image methodology and system quality control at the bank’s operations are the determinant factor when the SRC establishes the retention period, for the paper checks post imaging, and shall be determined after the awarding of this contact during the imaging certification process, which may include site inspections of both the imaging and destruction facility. The bank should be prepared for the possibility of storing checks for a period of three (3) to nine (9) months. Physical Destruction of Checks, Logs, and Reports Physical destruction of state records must comply with the existing (applicable) state standards as described in State Contract T-0387: Records Removal and Destruction Services. These standards will apply to any sub-contracted vendors the bank may utilize for destruction services. Specifically relating to the destruction of canceled checks; 1. The bank or sub-contractor shall only destroy public records that have been authorized for destruction by the NJDARM through a completed and processed “Request and Authorization for Records Disposal” form. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

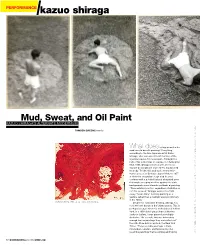

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14: NIGHT of DESTRUCTION September 11

INSIDE THIS EDITION SEPTEMBER 14 – NIGHT OF DESTRUCTION SEPTEMBER 27 – SUPER SHOE WEEKEND STARTS OCTOBER 26 – AWARDS BANQUET PHOTO MEDLEY – RACING FAMILIES September 11, 2019 SATURDAY SEPTEMBER 14 THE LEGENDARY NIGHT OF DESTRUCTION w SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14: NIGHT OF DESTRUCTION This Saturday. The Legendary Night of Destruction. We’ve got PROGRAM INFORMATION fan favorites: Monster Trucks . Bus Races . Trailer Races . Spectator Drags . Mini FWD Enduro . Demolition Derby. We Free Bus Rides 5:00 – 7:00 haven’t seen a Jet Car do its thing in years, but you’ll see (and Adults $20 hear) one this year. And then there is the new: Double-decker Youth 6-12 $10 Stacker Cars (first time in Michigan) . Scarecrow World Record Kids 5 & Under FREE Limo Jump plus another new Scarecrow stunt (they are never Program Starts 7:30 PM dull!) Then we close out the night with FIREWORKS!! Family fun awaits. We will see you at the 2019 Night of Destruction. w Clockwise: Monster trucks from a past Night of Destruction; cars with trailers go for the win while going around piles of debris (“ground clutter” as announcer, Jason Seltzer says); Scarecrow flies through several campers at last year’s Night of Destruction; fans watch the action; the Demolition Derby from the Red, White & Boom; the free bus rides are a big hit and the drivers sometimes get a bit competitive with one another; the Zoo Stacker cars will make their first Michigan appearance at this year’s night of Destruction. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 – SUPER SHOE WEEKEND STARTS There were 388 campsites available to reserve in advance for Super Shoe weekend (no need to run in the Footrace!) By publication time for this edition of Track Talk (Tuesday, September 10), there were only 11 of the 388 remaining. -

Puka-Puka Parade

100TH INFANTRY BATTALION VETERANS CLUB Puka-Puka Parade MAY 2014 !! ! ! ! ! ! NO. 04/2014 President’s Message and an evening kick-off fundraiser for the Nisei Veterans by Lloyd Kitaoka Legacy Center (NVLC). The month of May means Mother’s Day and I would like The NVLC is a separate 501(c)(3) entity incorporated in to wish all mothers a Happy Mother’s Day! Since I lost 2012; it is supported by six Nisei American veterans- th my mom this past December, it will be a sad time because related organizations, including the 100 Infantry nd this will be the first Mother’s Day without her. It got me Battalion Veterans, the 442 RCT Veterans, the Military th th thinking about the unsung heroes of our 100th, the wives Intelligence Service, the 1399 Engineers, the 100 nd and widows. Our vets receive all the glory and honor and Infantry Legacy Organization, and the 442 RCT rightly so, but I’d like to use this column to honor their Foundation who have representation on the NVLC Board. “better halves.” Some of them are not mothers but I’d like Its mission is “to preserve, perpetuate and share the to recognize them too. They work in the background but legacy of the AJAs who served in World War II, and to truly are the backbone of our organization. The sacrifices recognize the socio-economic changes brought about in they go through to support their husbands and children are Hawaii because of their extraordinary wartime service.” simply amazing. They do this all with very little credit. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R.