1 Inter(Acting)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATIONS with WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW

NOMINATIONS WITH WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW SPECIAL AWARD JEFF POPE LEADING ACTOR BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Sherlock – BBC One TOBY JONES Marvellous – BBC Two JAMES NESBITT The Missing – BBC One *JASON WATKINS The Lost Honour of Christopher Jefferies - ITV LEADING ACTRESS *GEORGINA CAMPBELL Murdered by My Boyfriend – BBC Three KEELEY HAWES Line of Duty – BBC Two SARAH LANCASHIRE Happy Valley – BBC One SHERIDAN SMITH Cilla - ITV SUPPORTING ACTOR ADEEL AKHTAR Utopia – Channel 4 JAMES NORTON Happy Valley – BBC One *STEPHEN REA The Honourable Woman – BBC Two KEN STOTT The Missing – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTRESS *GEMMA JONES Marvellous – BBC Two VICKY MCCLURE Line of Duty – BBC Two AMANDA REDMAN Tommy Cooper: Not like That, Like This - ITV CHARLOTTE SPENCER Glue – E4 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE *ANT AND DEC Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway – ITV LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One CLAUDIA WINKLEMAN Strictly Come Dancing – BBC One FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME OLIVIA COLMAN Rev. – BBC Two TAMSIN GREIG Episodes – BBC Two *JESSICA HYNES W1A – BBC Two CATHERINE TATE Catherine Tate’s Nan – BBC One MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME *MATT BERRY Toast of London – Channel 4 HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two TOM HOLLANDER Rev. – BBC Two BRENDAN O’CARROLL Mrs Brown’s Boys – Christmas Special – BBC One SINGLE DRAMA A POET IN NEW YORK Aisling Walsh, Ruth Caleb, Andrew Davies, Griff Rhys Jones - Modern Television/BBC Two COMMON Jimmy McGovern, David Blair, Colin McKeown, Donna -

LOGAN MARSHALL-GREEN Jewel

Festival de Cannes 2013 Un Certain Regard METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT présente une production Millennium Films en association avec Rabbit Bandini Productions et Lee Caplin/Picture Corporation un film de James Franco AS I LAY DYING James Franco Tim Blake Nelson Danny McBride Logan Marshall-Green Ahna O’Reilly Jim Parrack Beth Grant Brady Permenter Scénario : James Franco, Matt Rager D’après le livre Tandis que j’agonise de William Faulkner Durée : 1h50 Notre nouveau portail est à votre disposition. Inscrivez-vous à l’espace pro pour récupérer le matériel promotionnel du film sur : www.metrofilms.com Distribution : Relations presse : METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT MOONFLEET 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris Jérôme Jouneaux, Cédric Landemaine & Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 Mounia Wissinger Fax 01 53 57 84 02 10, rue d’Aumale - 75009 Paris Tél. 01 53 20 01 20 info@metropolitan -films.com cedric [email protected] Programmation : Partenariats et promotion : Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE MERCREDI Tél. 01 56 59 66 66 1 L’HISTOIRE Après le décès d’Addie Bundren, son mari et ses cinq enfants entament un long périple à travers le Mississippi pour accompagner la dépouille jusqu’à sa dernière demeure. Anse, le père, et leurs enfants Cash, Darl, Jewel, Dewey Dell et le plus jeune, Vardaman, quittent leur ferme sur une charrette où ils ont placé le cercueil. Chacun d’eux, profondément affecté, vit la mort d’Addie à sa façon. Leur voyage jusqu’à Jefferson, la ville natale de la défunte, sera rempli d’épreuves, imposées par la nature ou le destin. Mais pour ce qu’il reste de cette famille, rien ne sera plus dangereux que les tourments et les blessures secrètes que chacun porte au plus profond de lui… 2 NOTES DE PRODUCTION « Il faut deux personnes pour faire un homme, mais il n’en faut qu’une pour mourir. -

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 Baftas with 14 Nominations

HBO, Sky's 'Chernobyl' Leads 2020 BAFTAs with 14 Nominations 06.04.2020 HBO and Sky's Emmy-winning limited series Chernobyl tied Killing Eve's record, set last year, of 14 nominations at the 2020 BAFTA TV awards. That haul helped Sky earn a total of 25 nominations. The BBC led with a total of 79, followed by Channel 4 with 31. The series about the nuclear disaster that befell the Russian city was nominated best mini-series, with Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgård nommed best lead and supporting actor, respectively. Other limited series to score nominations were ITV's Confession, BBC One's The Victim and Channel 4's The Virtues. Netflix's The Crown, produced by Left Bank Pictures, was next with seven total nominations, including best drama and acting nominations for Oscar-winner Olivia Colman, who played Queen Elizabeth, and Helena Bonham Carter, who played Princess Margaret. Also nominated best drama were Channel 4 and Netflix's The End of the F***ig World, HBO and BBC One's Gentleman Jack and BBC Two's Giri/Haji. Besides Colman, dramatic acting nominations went to Glenda Jackson for BBC One's Elizabeth Is Missing, Emmy winner and last year's BAFTA winner Jodie Comer for BBC One's Killing Eve, Samantha Morton for Channel 4's I Am Kirsty and Suranne Jones for Gentleman Jack. Besides Harris, men nominated for lead actor include Callum Turner for BBC One's The Capture, Stephen Graham for The Virtues and Takehiro Hira for Giri/Haji. And besides Carter, other supporting actress nominations went to Helen Behan for The Virtues, Jasmine Jobson for Top Boy and Naomi Ackie for The End of the F***ing World. -

Joel Devlin Director of Photography

Joel Devlin Director of Photography Credits include: WILLOW Director: Debs Paterson High Fantasy Action Adventure Drama Series Showrunner: Wendy Mericle Writer/Executive Producer: Jon Kasdan Executive Producers: Ron Howard, Kathleen Kennedy Roopesh Parekh, Michelle Rejwan Producer: Tommy Harper Featuring: Ellie Bamber, Erin Kellyman, Warwick Davis Production Co: Imagine Entertainment / Lucasfilm / Disney+ ALEX RIDER Director: Rebecca Gatward Action Adventure Spy Series Producer: Richard Burrell Featuring: Otto Farrant, Vicky McClure, Stephen Dillane Production Co: Eleventh Hour Films / Amazon ITV Studios / Sony Pictures Television THE BEAST MUST DIE Director: Dome Karukoski Crime Drama Producer: Sarada McDermott Featuring: Jared Harris, Cush Jumbo, Billy Howle Production Co: New Regency Television International / BritBox THE SPANISH PRINCESS Director: Rebecca Gatward Tudor Period Drama Series Showrunner: Matthew Graham Featuring: Charlotte Hope, Ruari O’Connor, Olly Rix Production Co: New Pictures / Starz! HIS DARK MATERIALS: THE SUBTLE KNIFE Director: Leanne Welham Epic Fantasy Adventure Drama Series Series Producer: Roopesh Parekh Adaptation of Philip Pullman’s award-winning novel. Featuring: Dafne Keen, Ruth Wilson, Lin-Manuel Miranda ‘Will’s World’ for HIS DARK MATERIALS: NORTHERN LIGHTS Director Will McGregor Producer: Laurie Borg Production Co: Bad Wolf / HBO / BBC One THE TRIAL OF CHRISTINE KEELER Directors: Andrea Harkin, Leanne Welham Dramatisation of the infamous Profumo Affair Producer: Rebecca Ferguson that rocked the British -

4. UK Films for Sale at EFM 2019

13 Graves TEvolutionary Films Cast: Kevin Leslie, Morgan James, Jacob Anderton, Terri Dwyer, Diane Shorthouse +44 7957 306 990 Michael McKell [email protected] Genre: Horror Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Director: John Langridge Home Office tel: +44 20 8215 3340 Status: Completed Synopsis: On the orders of their boss, two seasoned contract killers are marching their latest victim to the ‘mob graveyard’ they have used for several years. When he escapes leaving them no choice but to hunt him through the surrounding forest, they are soon hopelessly lost. As night falls and the shadows begin to lengthen, they uncover a dark and terrifying truth about the vast, sprawling woodland – and the hunters become the hunted as they find themselves stalked by an ancient supernatural force. 2:Hrs TReason8 Films Cast: Harry Jarvis, Ella-Rae Smith, Alhaji Fofana, Keith Allen Anna Krupnova Genre: Fantasy [email protected] Director: D James Newton Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 7914 621 232 Synopsis: When Tim, a 15yr old budding graffiti artist, and his two best friends Vic and Alf, bunk off from a school trip at the Natural History Museum, they stumble into a Press Conference being held by Lena Eidelhorn, a mad Scientist who is unveiling her latest invention, The Vitalitron. The Vitalitron is capable of predicting the time of death of any living creature and when Tim sneaks inside, he discovers he only has two hours left to live. Chased across London by tabloid journalists Tooley and Graves, Tim and his friends agree on a bucket list that will cram a lifetime into the next two hours. -

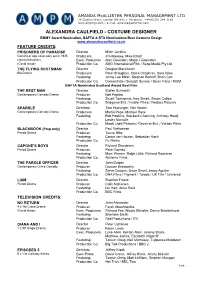

Alexandra Caulfield - Costume Designer

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44(0)207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] ALEXANDRA CAULFIELD - COSTUME DESIGNER EMMY Award Nomination, BAFTA & RTS Nominations Best Costume Design www.alexandracaulfield.co.uk FEATURE CREDITS: PRISONERS OF PARADISE Director Mitch Jenkins Coming of age Love story set in 1925 Producers Jim Mooney, Mike Elliott colonial Mauritius Exec. Producers Alan Govinden, Maria J Govinden (Covid shoot) Production Co. AMG International Film / Sega Media Pty Ltd THE FLYING SCOTSMAN Director Douglas Mackinnon Bio Drama Producers Peter Broughan, Claire Chapman, Sara Giles Featuring Jonny Lee Miller, Stephen Berkoff, Brian Cox Production Co. ContentFilm / Scottish Screen / Scion Films / MGM BAFTA Nominated Scotland Award Best Film THE BEST MAN Director Stefan Schwartz Contemporary Comedy Drama Producer Neil Peplow Featuring Stuart Townsend, Amy Smart, Simon Callow Production Co. Endgame Ent. / Insider Films / Redbus Pictures SPARKLE Directors Tom Hunsinger, Neil Hunter Contemporary Comedy Drama Producers Martin Pope, Michael Rose Featuring Bob Hoskins, Stockard Channing, Anthony Head, Lesley Manville Production Co. Magic Light Pictures / Revolver Ent. / Vertigo Films BLACKBOOK (Prep only) Director Paul Verhoeven Period Drama Producer Teune Hilte Featuring Carice van Houten, Sebastian Koch Production Co. Fu Works CAPONE’S BOYS Director Richard Standeven Period Drama Producer Peter Barnes Featuring Marc Warren, Ralph Little, Richard Rowntree Production Co. Alchemy Films THE PAROLE OFFICER Director John Duigan Contemporary Crime Comedy Producer Duncan Kenworthy Featuring Steve Coogan, Omar Sharif, Jenny Agutter Production Co. DNA Films / Figment / Toledo / UK Film / Universal LIAM Director Stephen Frears Period Drama Producer Colin McKeown Featuring Ian Hart, Anne Reid Production Co. -

Current Film Slate

CURRENT PROJECTS Updated 06 August 2021 For more information on any of the projects listed below, please contact the Premier film team as follows: • Email: [email protected] • Visit our website: https://www.premiercomms.com/specialisms/film/public-relations UK DISTRIBUTION NIGHT OF THE KINGS UK release date: 23 July 2021 (in cinemas) Directed by: Philippe Lacôte Starring: Koné Bakary, Barbe Noire, Steve Tientcheu, Rasmané Ouédraogo, Issaka Sawadogo, Digbeu Jean Cyrille Lass, Abdoul Karim Konaté, Anzian Marcel Laetitia Ky, Denis Lavant Running time: 93 mins Certificate: 12A UK release: 23 July 2021 Premier contacts: Annabel Hutton, Simon Bell, Josh Glenn When a young man (first-timer Koné Bakary) is sent to an infamous prison, located in the middle of the Ivorian forest and ruled by its inmates, he is chosen by the boss 'Blackbeard' (Steve Tientcheu, BAFTA and Academy-Award nominated LES MISÉRABLES) to take part in a storytelling ritual just as a violent battle for control bubbles to the surface. After discovering the grim fate that awaits him at the end of the night, Roman begins to narrate the mystical life of a legendary outlaw to make his story last until dawn and give himself any chance of survival. JOLT UK release date: 23 July 2021 (Amazon Prime Video) Directed by: Tanya Wexler Starring: Kate Beckinsale, Bobby Cannavale, Jai Courtney, Laverne Cox, David Bradley, Ori Pfeffer, Susan Sarandon, Stanley Tucci Running time: 91 mins Certificate: TBC UK release: Amazon Studios Premier contacts: Matty O’Riordan, Monique Reid, Brodie Walker, Priyanka Gundecha Lindy is a beautiful, sardonically-funny woman with a painful secret: Due to a lifelong, rare neurological disorder, she experiences sporadic rage-filled, murderous impulses that can only be stopped when she shocks herself with a special electrode device. -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Susannah Buxton - Costume Designer

SUSANNAH BUXTON - COSTUME DESIGNER THE TIME OF THEIR LIVES Director: Roger Goldby. Producer: Sarah Sulick. Starring: Joan Collins and Pauline Collins. Bright Pictures. POLDARK (Series 2) Directors: Charles Palmer and Will Sinclair. Producer: Margaret Mitchell. Starring: Aiden Turner and Eleanor Tomlinson. Mammoth Screen. LA TRAVIATA AND THE WOMEN OF LONDON Director: Tim Kirby. Producer: Tim Kirby. Starring: Gabriela Istoc, Edgaras Montvidas and Stephen Gadd. Reef Television. GALAVANT Directors: Chris Koch, John Fortenberry and James Griffiths. Producers: Chris Koch and Helen Flint. Executive Producer: Dan Fogelman. Starring: Timothy Omundson, Joshua Sasse, Mallory Jansen, Karen David Hugh Bonneville, Ricky Gervais, Rutger Hauer and Vinnie Jones. ABC Studios. LORD LUCAN Director: Adrian Shergold. Producer: Chris Clough. Starring: Christopher Ecclestone, Michael Gambon, Anna Walton and Rory Kinnear. ITV. BURTON & TAYLOR Director: Richard Laxton. Producer: Lachlan MacKinnon. Starring: Helena Bonham-Carter and Dominic West. BBC. RTS CRAFT AND DESIGN AWARD 2013 – Best Costume Design. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] DOWNTON ABBEY (Series I, Series II, Christmas Special) Directors: Brian Percival, Brian Kelly and Ben Bolt. Series Producer: Liz Trubridge. Executive Producer: Gareth Neame. Starring Hugh Bonneville, Jim Carter, Brendan Coyle, Michelle Dockery, Joanne Froggatt, Phyllis Logan, Maggie Smith and Elizabeth McGovern. Carnival Film & Television. EMMY Nomination 2012 – Outstanding Costumes for a Series. BAFTA Nomination 2012 – Best Costume Design. COSTUME DESIGNERS GUILD (USA) AWARD 2012 – Outstanding Made for TV Movie or MiniSeries. EMMY AWARD 2011 – Outstanding Costume Design. (Series 1). Emmy Award 2011 – Outstanding Mini-Series. Golden Globe Award 2012 – Best Mini Series or Motion Picture made for TV. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Director-General's Introduction

Director-General’s introduction Across the UK, virtually everyone gets something from the At the core of the BBC’s role is BBC each and every week. This report sets out how we are delivering our programmes and services to audiences, our vision something very simple, very democratic for the future, and how we spend the licence fee. It sets out our achievements, and highlights some of the challenges we face in and very important – to bring the best continuing to deliver for everyone. to everyone. Wherever you are – This year there is a lot to be proud of. whoever you are – whether you are On BBC One, Britain’s favourite channel, we have brought the nation together to celebrate, to commemorate, and to share rich or poor, old or young, that’s what amazing television moments. We saw history being made on Centre Court last summer; Sherlock’s unforgettable return to we do… Everybody deserves the best. our screens; and, more recently, Sarah Lancashire’s unmatched Tony Hall, Director-General performance in Happy Valley. With BBC News I believe that Britain has the best news organisation in the world. It offers a unique service: a network that is local, regional, national and global. This year I have been particularly pleased at the way our local radio stations responded to the terrible weather this winter; and our journalism in Syria, and in covering the conflict in Ukraine has been first-rate. The BBC is by far the most trusted news service in the UK, and the most retweeted source of news the world over – these are achievements to be rightly proud of. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 24 No. 67, July 22, 1992

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 7-22-1992 Central Florida Future, Vol. 24 No. 67, July 22, 1992 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 24 No. 67, July 22, 1992" (1992). Central Florida Future. 1143. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/1143 • NEWSp.3 OPINIONp.S FEATURES p. 8 · UCF parking problems Malcolm X gear is not Summer movies that put on front bumer for the uninformed deserve failing grades entra uture Serving The University of Central Florida Since 1968 Vol. 24, No. 67 WEDNESDAY July 22, 1992 _ . 8 Pages Student Senate appoints senator, justice • Jennifer M. Burgess as justice to the Judicial Council. "fd like to find something for suggestion box in the Business has experienre making decisions. Massmini is a member of the my last year of college to dedi- Administration Building. She said her friends usually ask STAFF REPORTER • Student Accounting. =i catemyselfto,"hesaid. Pho said that she has always for her opinion when dealing with Student Government ap- Society, the U.S. Coast ,I .~1 . _! 1 ; Massmini said he wanted to become active in SG problems and she is able to give pointed a new senator andjusice GuardReservesandthe !·;p-- ~ @·.