Managing Public Expenditure - a Reference Book for Transition Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Open Letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime

An open letter to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Finance, from fourteen leading New Zealand international aid agencies No-one is safe until we are all safe 28 April 2020 Dear Prime Minister Ardern, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Affairs Minister Peters, and Finance Minister Robertson, We thank you for the unprecedented steps your government has taken to protect people in New Zealand from the coronavirus and its impacts. Today, we ask that you extend assistance to people in places far less able to withstand this pandemic. With your inspiring leadership and guidance, here in New Zealand we have accepted the need for radical action to stop the coronavirus and are coping as best we can. Yet, as you know, even with all your government has done to support people through these hard times, people remain worried about their health and their jobs. Like here, family life has been turned upside down across the world. It’s hard to imagine families crammed into refugee camps in Iraq and Syria, or in the squatter settlements on the outskirts of Port Moresby, living in close quarters, with no clean water close by, no soap, and the knowledge that there will be little help from struggling public health systems. We’ve all become experts at hand washing and staying at home as we try to stop coronavirus and save lives. It is not easy, but we know how crucial it is to stop the virus. What would it be like trying to do this at a single tap in your part of the refugee camp, that 250 other people also rely on? This is the reality for more than 900,000 people in Cox’s Bazaar refugee camp in Bangladesh. -

The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint As Finance Minister to Balance the Budget?

1188 Discussion Papers Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung 2012 The Perfect Finance Minister Whom to Appoint as Finance Minister to Balance the Budget? Beate Jochimsen and Sebastian Thomasius Opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views of the institute. IMPRESSUM © DIW Berlin, 2012 DIW Berlin German Institute for Economic Research Mohrenstr. 58 10117 Berlin Tel. +49 (30) 897 89-0 Fax +49 (30) 897 89-200 http://www.diw.de ISSN print edition 1433-0210 ISSN electronic edition 1619-4535 Papers can be downloaded free of charge from the DIW Berlin website: http://www.diw.de/discussionpapers Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin are indexed in RePEc and SSRN: http://ideas.repec.org/s/diw/diwwpp.html http://www.ssrn.com/link/DIW-Berlin-German-Inst-Econ-Res.html The perfect finance minister: Whom to appoint as finance minister to balance the budget? Beate Jochimsen Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Sebastian Thomasius∗ Free University of Berlin Berlin School of Economics and Law German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) February 2012 Abstract The role and influence of the finance minister within the cabinet are discussed with increasing prominence in the recent theoretical literature on the political economy of budget deficits. It is generally assumed that the spending ministers can raise their reputation purely with new or more extensive expenditure programs, whereas solely the finance minister is interested to balance the budget. Using a dynamic panel model to study the development of public deficits in the German states between 1960 and 2009, we identify several personal characteristics of the finance ministers that significantly influence budgetary performance. -

Afghanistan H.E. Abdul Hadi Arghandiwal Acting Minister of Finance Ministry of Finance Pashtoonistan Maidan Kabul Afghanistan Mr

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE AUTHORIZED INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES REPRESENTATIVE AND ALTERNATE REPRESENTATIVE Member Representative Alternate Representative Afghanistan H.E. Abdul Hadi Arghandiwal Mr. Abul Habib Zadran Acting Minister of Finance Deputy Minister for Finance Ministry of Finance Ministry of Finance Pashtoonistan Maidan Pashtoonistan Maidan Kabul Kabul Afghanistan Afghanistan Albania H.E. Ms. Anila Denaj Ms. Luljeta Minxhozi Minister of Finance and Economy Deputy Governor Ministry of Finance and Economy Bank of Albania Boulevard Deshmoret E. Kombit, No. 3 Sheshi "Skenderbej", No. 1 Tirana Tirana Albania Albania Algeria H.E. Aimene Benabderrahmane Mr. Ali Bouharaoua Minister of Finance Director General Ministere des Finances Economic and Financial External Affairs Immeuble Ahmed Francis Ministere des Finances Ben Aknoun Immeuble Ahmed Francis Algiers 16306 Ben Aknoun Algeria Algiers 16306 Algeria Argentina H.E. Gustavo Osvaldo Beliz Mr. Christian Gonzalo Asinelli Secretary of Strategic Affairs Under Secretary of International Financial Office of the President Relations for Development Balarce 50 Office of the President Buenos Aires Balarce 50 Argentina Buenos Aires Argentina Armenia H.E. Atom Janjughazyan Mr. Armen Hayrapetyan Minister of Finance First Deputy Minister of Finance Ministry of Finance Ministry of Finance Government House 1 Government House 1 Melik-Adamian St. 1 Melik-Adamian St. 1 Yerevan 0010 Yerevan 0010 Armenia Armenia Corporate Secretariat March 24, 2021 1 PUBLIC DISCLOSURE AUTHORIZED INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SETTLEMENT OF INVESTMENT DISPUTES REPRESENTATIVE AND ALTERNATE REPRESENTATIVE Member Representative Alternate Representative Australia Hon. Josh Frydenberg MP Hon. Michael Sukkar MP Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia Assistant Treasurer Parliament House Parliament House Parliament Dr. Parliament Dr. Canberra ACT 2600 Canberra ACT 2600 Australia Australia Austria H.E. -

Modi: Two Years On

Modi: Two Years On Hudson Institute September 2016 South Asia Program Research Report Modi: Two Years On Aparna Pande, Director, India Initiative Husain Haqqani, Director, South and Central Asia South Asia Program © 2016 Hudson Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. For more information about obtaining additional copies of this or other Hudson Institute publications, please visit Hudson’s website, www.hudson.org ABOUT HUDSON INSTITUTE Hudson Institute is a research organization promoting American leadership and global engagement for a secure, free, and prosperous future. Founded in 1961 by strategist Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute challenges conventional thinking and helps manage strategic transitions to the future through interdisciplinary studies in defense, international relations, economics, health care, technology, culture, and law. Hudson seeks to guide public policy makers and global leaders in government and business through a vigorous program of publications, conferences, policy briefings and recommendations. Visit www.hudson.org for more information. Hudson Institute 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20004 P: 202.974.2400 [email protected] www.hudson.org Table of Contents Overview 5 Defense 13 Self-Sufficiency 14 Challenges and Opportunities 15 Education and Skill Development 18 Background 18 Modi Administration on Education 20 Prime Minister Modi’s Interventions in Skill Development 20 Challenges and Opportunities 21 India’s Energy Challenge 23 Coal 23 Petroleum 24 Natural Gas 25 Nuclear 27 Renewables 28 Challenges -

Bellagio Housing Declaration

More than Shelter: Housing as an Instrument of Economic and Social Development The Bellagio Housing Conference organized by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University supported by the Rockefeller Foundation May 2005 BELLAGIO HOUSING DECLARATION We, the participants in the Bellagio Housing Conference, having come from five countries — Kenya, Mexico, South Africa, Thailand and the USA—together affirm that sound, sanitary and affordable housing for all is central to the wellbeing of nations. Housing is indeed more than shelter: it is a powerful engine that creates opportunity and economic growth. We affirm the following principles: • Housing as a sustained national priority: Housing is a long term process that requires a stable policy framework and demands national priority attention. • Housing as an engine of social and economic development: Housing brings significant benefits in terms of employment creation, domestic capital mobilization and social wellbeing in the face of the major challenges posed by population growth and urbanization. • Housing as an element of wealth: Equity in housing is a basic source of personal and family wealth and can reduce asset poverty. Owning a home is a powerful incentive to save, work harder and commit to strengthening the community. • Housing as connected markets: Well functioning primary and secondary housing markets should provide diverse housing opportunities and secure tenure forms for all. Reducing the gap between low income affordability and the cost of housing requires access to financial instruments that make demand effective. It also requires efforts on the supply-side to reduce the cost of land, basic infrastructure and housing construction. • Housing and government: Government must play an active and appropriate role in enabling, regulating, facilitating and supporting healthy housing markets and housing finance systems. -

United Nations TD/B/C.II/ISAR/INF.6

United Nations TD/B/C.II/ISAR/INF.6 United Nations Conference Distr.: General 2 December 2013 on Trade and Development English/French/Spanish only Trade and Development Board Investment, Enterprise and Development Commission Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on International Standards of Accounting and Reporting Thirtieth session Geneva, 6–8 November 2013 List of participants Note: The entries in this list and the format in which they are presented are as provided to the secretariat. GE.13- TD/B/C.II/ISAR/INF.6 Experts Angola Mr. Nelito Victor, Department Chief, Ministry of Finance Ms. Maria Neto, Public Officer, Ministry of Finance Argentina Mr. Hernan Pablo Casinelli, SME Implementation Group Member, Federacion Argentina de Consejos Profesionale de Ciencias Economicas Azerbaijan Mr. Nadir Garayev, Head, Treasury Department, Ministry of Finance Mr. Fuad Nasirov, Director, Project Management Unit, Ministry of Finance Mr. Azer Kerimov, Financial Manager, Ministry of Finance Mr. Elman Huseynov, Director, Financial Science and Training Centre, Ministry of Finance Bangladesh Mr. A.K.M. Delwer Hussein, President, Insitute of Cost and Management Accountants Mr. Md Abdus Salam, President, Institute of Chartered Accountants Barbados Ms. Marion Williams, Ambassador, Permanent Mission, Geneva Belarus Mr. Mikalai Saroka, Deputy Head, Accounting, Reporting and Audit Regulation Directorate, Ministry of Finance Ms. Tatsiana Rybak, Head, Accounting, Reporting and Audit Regulation Directorate, Ministry of Finance Belgium Ms. Muriel Vossen, Advisor, Ministry of Economy David Szafran, Director, PricewaterhouseCoopers, (Former Secretary-General of the Institute of Registered Auditors) Belgium (Chair of the thirtieth session of ISAR) Benin M. Arsène Narcisse Omichessan, Attaché, Mission Permanente, Genève M. Thomas Azandossessi, Directeur, Centre National de Formation Comptable/Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances, Ministère des Finances Brazil Mr. -

Economic Ties: a Window of Opportunity for Deeper Engagement

Economic Ties: A Window of Opportunity for Deeper Engagement ESWAR PRASAD rime Minister Narendra Modi’s government than last year. Indeed, in terms of positive growth mo- has picked up the pace of domestic reforms and mentum, the U.S. and India are the two bright spots seems increasingly willing to engage with foreign among the Group of Twenty (G20) economies. This Ppartners of all stripes as part of its strategy to promote provides a propitious environment for the two coun- growth. Of these partners, the United States shares a tries to strengthen their bilateral economic ties. considerable array of interests with India that provide a good foundation on which to build a strong bilateral An obvious dimension in which the two countries economic relationship. The challenge remains that of would benefit is providing broader access to each oth- framing these issues in a manner that highlights how er’s markets for both trade and finance. India is a rapidly making progress on them would be in the mutual inter- growing market for high-technology products (and the ests of the two countries. technology itself) that the U.S. can provide while the U.S. remains the largest market in the world, including India’s economic prospects have improved considerably for high-end services that India is developing a compar- since Modi took office. The economy has revived after ative advantage in. Both of these dimensions of bilateral hitting a rough patch in 2013-14, with GDP growth trade could fit into the rubric of Modi’s “Make in In- likely to exceed 6 percent in 2015, although the man- dia” campaign, turning that into a campaign to boost ufacturing sector continues to turn in a lackluster per- productivity in the Indian manufacturing and services formance. -

Public Financial Management Strategic Framework FY 2020/21-2024/25

Ministry of Health and Population Public Financial Management Strategic Framework FY 2020/21-2024/25 MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND POPULATION RAMSHAHPATH, KATHMANDU June 2020 Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 FINANCIAL POWER AT FEDERAL, PROVINCIAL AND LOCAL LEVEL ................................................ 2 1.3 DISTRIBUTION OF SOURCES OF REVENUE .................................................................................... 2 1.4 RELATIONS BETWEEN FEDERAL, PROVINCIAL AND LOCAL LEVELS ............................................... 3 1.5 LIST OF POWERS RELATED TO FEDERAL, PROVINCIAL AND LOCAL LEVELS .................................. 3 1.6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE ..................................................................................................... 3 1.7 CLASSIFICATION STANDARDS FOR HEALTH SERVICES TO BE PROVIDED AT FEDERAL, PROVINCIAL AND LOCAL LEVELS.................................................................................................................................... 3 1.8 1.2 VISION, MISSION TARGET, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGY OF MoHP ........................................ 4 CHAPTER 2: PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT ................................................................................................ 5 2.1 BACKGROUND -

LIST of PARTICIPANTS 7TH ANNUAL COORDINATION MEETING of the COMCEC WORKING GROUP FOCAL POINTS (15-17 July 2019, İstanbul)

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 7TH ANNUAL COORDINATION MEETING OF THE COMCEC WORKING GROUP FOCAL POINTS (15-17 July 2019, İstanbul) A. MEMBER COUNTRIES OF THE OIC ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN - Mr. ABDUL HADI NADIM Eco Desk Expert, Ministry of Transport - Mr. ALI AHMAD SAADAT Regional Development Director, Ministry of Economy - Mr. MOHAMMAD HUSSAIN PANAHI Senior Bilateral Economic Commissions Specialist, Ministry of Finance - Mr. MOHD WALI WAZIRI Head of M&E, Ministry of İndustries and Commerce - Mr. SHUJAUDDIN KARVANBASHI Cultural Attache, Embassy of Afghanistan REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA - Mr. ERIOLA SOJATI Expert, Ministry of Tourism and Environment PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA - Mr. DJAMAL ALILI Director of Thermal Activities, Ministry of Tourism and Crafts - Mr. DJAMEL ADOUANE Deputy Director, Ministry of Finance - Mr. SEDDIK MOHAMED Expert, Ministry of Transport - Mr. TAREK ALLOUNE Sub- Director, Ministry of Trade - Ms. AMEL YESREF Agricultural Statistic, Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development and Fisheries - Ms. SALIMA OUBOUSSAD Deputy Director, Ministry of National Solidarity, Family and Woman Condition REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN - Mr. GUNDUZ ALIYEV Deputy Head of the Department Policy on Financial Services, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Azerbaijan - Mr. RASHAD FARAJOV Head of the International Cooperation Department, Ministry of Agriculture - Mr. TEYMUR ABBASOV Chief Adviser, Ministry of Transport, Communications and High Technologies - Ms. GÜNAY BAYRAMOVA Head of Division, State Tourism Agency of the Republic of Azerbaijan KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN - Mr. RASHAD ALSHAIKH Counselor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs - Ms. SAWSAN AL HAMMADI Chief of Industrıal Relation and Support, Ministry of Industry Commerce and Tourism PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH - Ms. FARHANA ISLAM Deputy Secretary, Ministry of Commerce - Ms. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

xxxui CHRONOLOGY í-i: Sudan. Elections to a Constituent Assembly (voting postponed for 37 southern seats). 4 Zambia. Basil Kabwe became Finance Minister and Luke Mwan- anshiku, Foreign Minister. 5-1: Liberia. Robert Tubman became Finance Minister, replacing G. Irving Jones. 7 Lebanon. Israeli planes bombed refugee camps near Sidon, said to contain PLO factions. 13 Israel. Moshe Nissim became Finance Minister, replacing Itzhak Moda'i. 14 European Communities. Limited diplomatic sanctions were imposed on Libya, in retaliation for terrorist attacks. Sanctions were intensified on 22nd. 15 Libya. US aircraft bombed Tripoli from UK and aircraft carrier bases; the raids were said to be directed against terrorist head- quarters in the city. 17 United Kingdom. Explosives were found planted in the luggage of a passenger on an Israeli aircraft; a Jordanian was arrested on 18 th. 23 South Africa. New regulations in force: no further arrests under the pass laws, release for those now in prison for violating the laws, proposed common identity document for all groups of the population. 25 Swaziland. Prince Makhosetive Dlamini was inaugurated as King Mswati III. 26 USSR. No 4 reactor, Chernobyl nuclear power station, exploded and caught fire. Serious levels of radio-activity spread through neighbouring states; the casualty figure was not known. 4 Afghánistán. Mohammad Najibollah, head of security services, replaced Babrak Karmal as General Secretary, People's Demo- cratic Party. 7 Bangladesh. General election; the Jatiya party won 153 out of 300 elected seats. 8 Costa Rica. Oscar Arias Sánchez was sworn in as President. Norway. A minority Labour government took office, under Gro 9 Harlem Brundtland. -

GOVERNMENT of MEGHALAYA, OFFICE of the CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong ***

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA, OFFICE OF THE CHIEF MINSITER Media & Communications Cell Shillong *** New Delhi | Sept 9, 2020 | Press Release Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad K. Sangma and Deputy Chief Minister Prestone Tynsong today met Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in New Delhi and submitted memorandum requesting the Ministry of Finance to incentivise national banks and prioritize the setting up of new bank branches in rural areas to increase the reach of banking system in the State. Chief Minister also submitted a memorandum requesting the Government of India to increase Meghalaya’s share of central taxes. The Union Minister was also apprised on the overall financial position of Meghalaya. After meeting Union Finance Minister, Chief Minister and Dy Chief Minister also met Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur and discussed on way forward for initiating externally funded World Bank & New Development Bank projects in the state. He was also apprised of the 3 externally aided projects that focus on Health, Tourism & Road Infrastructure development in the State. Chief Minister and Dy CM also met Union Minister for Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Dairying Giriraj Singh and discussed prospects and interventions to be taken up in the State to promote cattle breeding, piggery and fisheries for economic growth and sustainable development. The duo also called on Minister of State Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises, Arjun M Meghwal and discussed various issues related to the introduction of electric vehicles, particularly for short distance public transport. Later in the day, Chief Minister met Union Minister for Minority Affairs, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi as part of his visit to the capital today. -

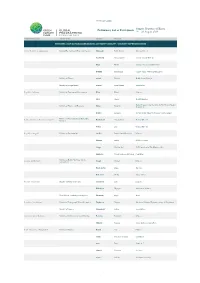

GCF Global Programming Conference

#GCFconnections Songdo, Republic of Korea Preliminary List of Participants 19 – 23 August 2019 COUNTRY/ORGANIZATION MINISTRY/AGENCY LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE MINISTERS / GCF NATIONAL DESIGNATED AUTHORITY (NDA/FP) / COUNTRY REPRESENTATIVES Islamic Republic of Afghanistan National Environmental Protection Agency Maiwandi Schah Zaman Director General Hoshmand Ahmad Samim Climate Change Director Khan Hamid Advisor - International Relations Bakhshi M.Solaiman Climate Finance Mechanisms Expert Ministry of Finance Salemi Wazhma Health Sector Manager Minitry of Foreign Affairs Atarud Abdul Hakim Ambassador Republic of Albania Ministry of Tourism and Environment Klosi Blendi Minister Çuçi Ornela Deputy Minister Budget Programming Specialist In The General Budget Ministry of Finance and Economy Muka Brunilda Department Demko Majlinda Adviser of The Minister of Finance and Economy Ministry of Environment and Renewable People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Boukadoum Abderrahmane General Director Energies Nouar Laib General Director Republic of Angola Ministry of Environment Coelho Paula Cristina Francisco Minister Massala Arlette GCF Focal Point Congo Mariano José GCF Consultant of The Minister office Lumueno Witold Selfroneo Da Gloria Consultant Minister of Health, Wellness and the Antigua and Barbuda Joseph Molwyn Minister Environment Black-Layne Diann Director Robertson Michai Policy Officer Republic of Armenia Ministry of Nature Protection Grigoryan Erik Minister Hakobyan Hayrapet Assistant to Minister Water Resources Management Agency Pirumyan