A Study in the Theologies of Hooker, Maurice, and Gore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

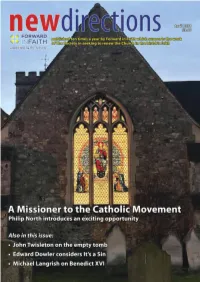

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900 Hancock, Christopher David How to cite: Hancock, Christopher David (1984) The priesthood of Christ in Anglican doctrine and devotion: 1827 - 1900, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7473/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 VOLUME II 'THE PRIESTHOOD OF CHRIST IN ANGLICAN DOCTRINE AND DEVOTION: 1827 -1900' BY CHRISTOPHER DAVID HANCOCK The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Durham, Department of Theology, 1984 17. JUL. 1985 CONTENTS VOLUME. II NOTES PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I 26 CHAPTER II 46 CHAPTER III 63 CHAPTER IV 76 CHAPTER V 91 CHAPTER VI 104 CHAPTER VII 122 CHAPTER VIII 137 ABBREVIATIONS 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 1 NOTES PREFACE 1 Cf. -

Ref No: JRH Extent: 5 Linear Metres Title: Papers of James Rendel Harris Date: C

CATALOGUE OF THE PAPERS OF JAMES RENDEL HARRIS HELD AT WOODBROOKE COLLEGE, SELLY OAK ___________________________________________________________________________ Collection description ___________________________________________________________________________ Ref No: JRH Extent: 5 linear metres Title: Papers of James Rendel Harris Date: c. 1880s-1960s Description: The papers of James Rendel Harris include notebooks and newspaper cuttings relating to his research on folklore and the history of the Pilgrim Fathers' ship, the Mayflower; and correspondence with other scholars and friends: Herbert George Wood, his secretary Irene Speller Pickard, Eric Wills, and L Violet Hodgkin. The collection contains many of his own copies of his books and essays, published and unpublished. These are often annotated and occasionally contain letters or other documents. There are also papers about him collected by Irene Speller Pickard during the writing of her book, 'Memories of James Rendel Harris'; and papers of Harris's nephew, John Major, concerning their research on the Egyptian origins of English place names, which was Harris's main research interest in the last years of his life. Arrangement: The papers have been divided into three groups (sub-fonds): papers created by Rendel Harris himself, and papers about him collected by Irene Pickard and by his nephew John Major. The first group has been arranged by record type into five series: press cuttings and research notes; notebooks; articles and lectures; correspondence; and books. The collection was originally listed using references beginning G Har. These correspond to the new references as follows: G Har 1 JRH 1/1/1 G Har 2 JRH 1/3/1 G Har 3 JRH 1/3/2 G Har 4 JRH 1/4/5 G Har 5 JRH 3 G Har 6 JRH 1/1/2 G Har 7 JRH 1/4/9 G Har 8 JRH 1/3/3 G Har 9 JRH 1/4/6 G Har 10 JRH 1/4/7 G Har 11 JRH 1/4/4 G Har 12 JRH 1/4/8 G Har 13 JRH 1/4/2 G Har 14 JRH 2 G Har 15 JRH 1/3/4 G Har 16 JRH 1/1/3-4 G Har 17 JRH 1/3/5 G Har 18 JRH 1/4/3 G Har 19 JRH 1/4/1 Access Conditions: Access to all registered researchers. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

CNI -February 2

February 2 ! CNI ! Anti-abortion campaigner Bernadette Smyth was among many in the the courtroom for the hearing Northern Ireland abortion law can be challenged, court rules The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission has won High Court permission to challenge abortion law in Northern Ireland. Irish Times - A judge in Belfast has granted leave to seek a judicial review amid claims the current near-blanket ban on terminations is a violation of human rights. [email protected] Page !1 February 2 “This case raises issues of considerable public importance which require to be examined at a substantive hearing,” Mr Justice Treacy said. The commission issued proceedings against the Department of Justice as part of an attempt to secure a change in the law to allow abortion in cases of rape, incest or serious foetal malformation. Terminations are currently only legal in Northern Ireland to protect the woman’s life or where there is a risk of permanent and serious damage to her mental or physical health. The court battle comes as Minister for Justice David Ford continues a public consultation on amending the criminal law on abortion in Northern Ireland. It includes a recommendation for proposed legislation allowing an abortion in circumstances where there is no prospect of the foetus being delivered and having a viable life. But according to counsel for the commission the consultation does not commit to making the changes it believes are necessary. [email protected] Page !2 February 2 In court, Nathalie Lieven QC argued the current situation breaches rights to freedom from torture and inhuman and degrading treatment, discrimination and entitlements to privacy under the European Convention on Human Rights. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

The Golden Cord

THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED ' " ' ..I ~·/ I _,., ' '4 ~ 'V . \ . " ': ,., .:._ C HARLE S TALIAFERR O THE GOLDEN CORD THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED CHARLES TALIAFERRO University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2012 by the University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taliaferro, Charles. The golden cord : a short book on the secular and the sacred / Charles Taliaferro. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04238-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04238-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. God (Christianity) 2. Life—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Self—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Redemption—Christianity. 5. Cambridge Platonism. I. Title. BT103.T35 2012 230—dc23 2012037000 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 Love in the Physical World 15 CHAPTER 2 Selves and Bodies 41 CHAPTER 3 Some Big Pictures 61 CHAPTER 4 Some Real Appearances 81 CHAPTER 5 Is God Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know? 107 CHAPTER 6 Redemption and Time 131 CHAPTER 7 Eternity in Time 145 CHAPTER 8 Glory and the Hallowing of Domestic Virtue 163 Notes 179 Index 197 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the patience, graciousness, support, and encour- agement of the University of Notre Dame Press’s senior editor, Charles Van Hof. -

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Defining Man As Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing C. 1650–C

Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. Title: Defining Man as Animal Religiosum in English Religious Writing c. 1650–c. 1700 Abstract: This article surveys the emergence and usage of the redefinition of man not as animal rationale (a rational animal) but as animal religiosum (a religious animal) by numerous English theologians between 1650 and 1700. Across the continuum of English protestant thought human nature was being re-described as unique due to its religious, not primarily its rational, capabilities. The article charts this appearance as a contribution to debates over man’s relationship with God; then its subsequent incorporation into the subsequent debate over the theological consequences of arguments in favor of animal rationality, as well as its uses in anti-atheist apologetics; and then the sudden disappearance of the definition of man as animal religiosum at the beginning of the eighteenth century. In doing so, the article hopes to make a useful contribution to our understanding of changing early modern understandings of human nature by reasserting the significance of theological debates within the context of seventeenth-century debate about the relationship between humans and beasts and by offering a more wide-ranging account of man as animal religiosum than the current focus on ‘Cambridge Platonism’ and ‘Latitudinarianism’ allows. Keywords: Animal rationality, reason, 17th c. England, Cambridge Platonism, Latitudinarianism. Contact Details: Dr R J W Mills Dept. of History, University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT United Kingdom [email protected] 1 Accepted for publication in Church History for publication in September 2019. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Convictions, Conflict and Moral Reasoning McMillan, D.J. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) McMillan, D. J. (2019). Convictions, Conflict and Moral Reasoning: The Contribution of the Concept of Convictions in Understanding Moral Reasoning in the Context of Conflict, Illustrated by a Case Study of Four Groups of Christians in Northern Ireland. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT CONVICTIONS, CONFLICT AND MORAL REASONING The Contribution of the Concept of Convictions in Understanding Moral Reasoning in the Context of Conflict, Illustrated by a Case Study of Four Groups of Christians in Northern Ireland ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor of Philosophy aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal

Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal Summer 2021 — Volume 5.2 A quarterly journal for debate on current issues in the Anglican Communion and beyond Scottish Episcopal Institute Journal Volume 5.2 — Summer 2021 — ISSN 2399-8989 ARTICLES Introduction to the Summer Issue on Scottish Episcopal Theologians Alison Peden 7 William Montgomery Watt and Islam Hugh Goddard 11 W. H. C. Frend and Donatism Jane Merdinger 25 Liberal Values under Threat? Vigo Demant’s The Religious Prospect 80 Years On Peter Selby 33 Donald MacKinnon’s Moral Philosophy in Context Andrew Bowyer 49 Oliver O’Donovan as Evangelical Theologian Andrew Errington 63 Some Scottish Episcopal Theologians and the Arts Ann Loades 75 Scottish Episcopal Theologians of Science Jaime Wright 91 Richard Holloway: Expectant Agnostic Ian Paton 101 SCOTTISH EPISCOPAL INSTITUTE JOURNAL 3 REVIEWS Ann Loades. Grace is not Faceless: Reflections on Mary Reviewed by Alison Jasper 116 Hannah Malcolm and Contributors. Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church Reviewed by James Currall 119 David Fergusson and Mark W. Elliott, eds. The History of Scottish Theology, Volume I: Celtic Origins to Reformed Orthodoxy Reviewed by John Reuben Davies 121 Stephen Burns, Bryan Cones and James Tengatenga, eds. Twentieth Century Anglican Theologians: From Evelyn Underhill to Esther Mombo Reviewed by David Jasper 125 Nuria Calduch-Benages, Michael W. Duggan and Dalia Marx, eds. On Wings of Prayer: Sources of Jewish Worship Reviewed by Nicholas Taylor 127 Al Barrett and Ruth Harley. Being Interrupted: Reimagining the Church’s Mission from the Outside, In Reviewed by Lisa Curtice 128 AUTISM AND LITURGY A special request regarding a research project on autism and liturgy Dr Léon van Ommen needs your help for a research project on autism and liturgy. -

Robert D. Hawkins

LEX OR A NDI LEX CREDENDI THE CON F ESSION al INDI ff ERENCE TO AL TITUDE Robert D. Hawkins t astounds me that, in the twenty-two years I have shared Catholics, as the Ritualists were known, formed the Church Iresponsibility for the liturgical formation of seminarians, of England Protection Society (1859), renamed the English I have heard Lutherans invoke the terms “high church” Church Union (1860), to challenge the authority of English and “low church” as if they actually describe with clar- civil law to determine ecclesiastical and liturgical practice.1 ity ministerial positions regarding worship. It is assumed The Church Association (1865) was formed to prosecute in that I am “high church” because I teach worship and know civil court the “catholic innovations.” Five Anglo-Catholic how to fire up a censer. On occasion I hear acquaintances priests were jailed following the 1874 enactment of the mutter vituperatively about “low church” types, apparently Public Worship Regulation Act for refusing to abide by civil ecclesiological life forms not far removed from amoebae. court injunctions regarding liturgical practices. Such prac- On the other hand, a history of the South Carolina Synod tices included the use of altar crosses, candlesticks, stoles included a passing remark about liturgical matters which with embroidered crosses, bowing, genuflecting, or the use historically had been looked upon in the region with no lit- of the sign of the cross in blessing their congregations.2 tle suspicion. It was feared upon my appointment, I sense, For readers whose ecclesiological sense is formed by that my supposed “high churchmanship” would distract notions about the separation of church and state, such the seminarians from the rigors of pastoral ministry into prosecution seems mind-boggling, if not ludicrous.